(For a quick summary of this post, see “Fusing Arts, Culture and Social Change: the condensed version.”)

Holly Sidford’s “Fusing Arts, Culture and Social Change: High Impact Strategies for Philanthropy” calls for a major overhaul in arts philanthropy in the United States. It is one of a series of reports commissioned by the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP) as a follow-up to its 2009 Criteria for Philanthropy at Its Best: Benchmarks to Assess and Enhance Grantmaker Impact. NCRP established benchmarks for funders to strive toward in order to “maximize their impact and best serve nonprofits, vulnerable communities and the common good.” Those criteria, along with their associated benchmarks, are as follows:

- Values: at least 50% of grant dollars provided to benefit marginalized communities (defined broadly using 11 categories, which include the economically disadvantaged; racial/ethnic minorities; victims of crime/abuse; single parents; and LGBTQ citizens), and 25% for advocacy and civic engagement

- Effectiveness: providing at least 50% of grant dollars for general operating support and 50% as multiyear grants, and ensuring that application and reporting timelines are aligned to grant size

- Ethics: maintaining a board that serves without compensation and includes representatives from the community it serves

- Commitment: paying out a minimum of 6% of a foundation’s assets annually in grants, and investing at least 25% of those assets in ways that align with its mission.

“Fusing Arts, Culture, and Social Change” examines how current practice in arts funding holds up against the NCRP benchmarks, and calls on the field to refocus its energies and resources in a number of different ways.

Summary

The central argument of “Fusing” is that arts philanthropy, as currently structured, perpetuates inequality across the arts and culture sector, and across society as a whole, by disproportionately funding large institutions that focus on Western European traditions. According to the report, this practice is problematic for a number of reasons:

- It “restricts the expressive lives” of a large swath of our society

- It benefits institutions patronized primarily by the wealthy, and, by extension, benefits the wealthy themselves, flouting justification for the tax-exempt status foundations and arts organizations enjoy

- It ignores emerging practices within the artistic landscape, threatening to render arts philanthropy irrelevant

- It undermines the potential of arts and culture to be tools promoting democracy and social change

This practice is not new. Arts philanthropy, Sidford argues, was from its early days “not motivated by a desire to relieve suffering, help the poor or find systemic solutions to pressing social problems,” but to reinforce an elitist system in which wealthy individuals patronized museums and orchestras to signal their status. Arts and culture philanthropy was firmly divorced from any funding meant to address social inequity. To this day, “early arts patrons’ preference for the European high art canon, and for the institutions that reflect and support social elites, continues to frame funding patterns.” To support this claim, “Fusing” examines Foundation Center data on how many funding allocations for arts and culture are made with the specific intention of benefiting disadvantaged communities:

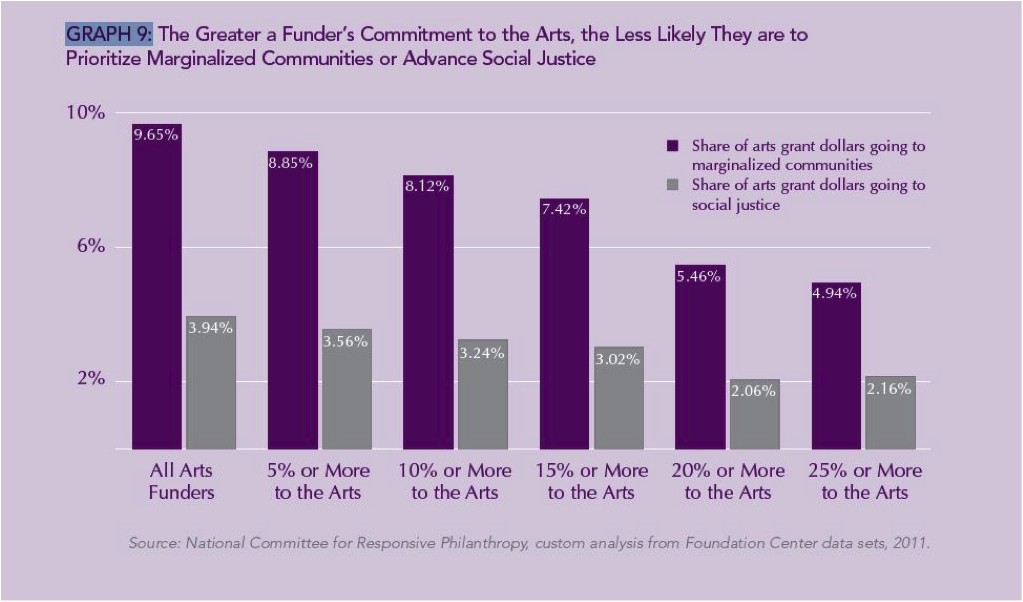

95% of the foundations analyzed gave grants with a primary or secondary purpose of arts and culture. But only 10% of these arts and culture grant dollars were classified as benefiting one of the 11 underserved populations included in the NCRP’s analysis, and only 4 percent were classified as advancing social justice goals.

Furthermore, the Foundation Center data suggests “the greater a funder’s commitment to the arts, the less likely it is to prioritize marginalized communities or advance social justice in its arts grantmaking… arts funders whose main focus lies outside of the arts appear to value the catalytic role of the arts in serving social justice goals more than funders with larger arts portfolios.”

Sidford cites a number of present-day factors – demographic, aesthetic/artistic, and economic – that she believes make the case for change in philanthropic practice all the more pressing.

Demographics

“Fusing”’s demographic data, mainly drawn from the 2010 U.S. Census, centers on the changing racial and ethnic composition of the United States, the widening gap between the rich and poor, and persistent inequities in education, civic participation and health care. Each of these inequities, according to Sidford, is currently being addressed in some way by artist-activists and community-based cultural organizations that are not receiving the recognition or support they deserve. Their existence, and the fact that there has been an “enormous increase in the number of cultural organizations in the past two decades,” underscores the “universal desire for arts and culture in every community” – a desire that needs to be acknowledged with broader philanthropic support.

Artistic/Aesthetic

Despite being persistently undervalued and underpaid, artists play a vital role in preserving non-European cultural traditions, contemporizing and blending them to create new ones, and breaking new ground in finding ways to apply the arts toward social justice goals. “Fusing” cites Americans for the Arts’ 2010 “Trend or Tipping Point: Arts and Social Change Grantmaking,” which reports growing funder interest in supporting arts and culture projects that intersect with other social justice goals such as health and education. Many organizations engaged in this type of hybrid work, however, “do not fit the classic model of an arts institutions, operating more on a collectivist or community organizing model” that renders them difficult to assess or to assign to a particular funding category.

Cultural Economics

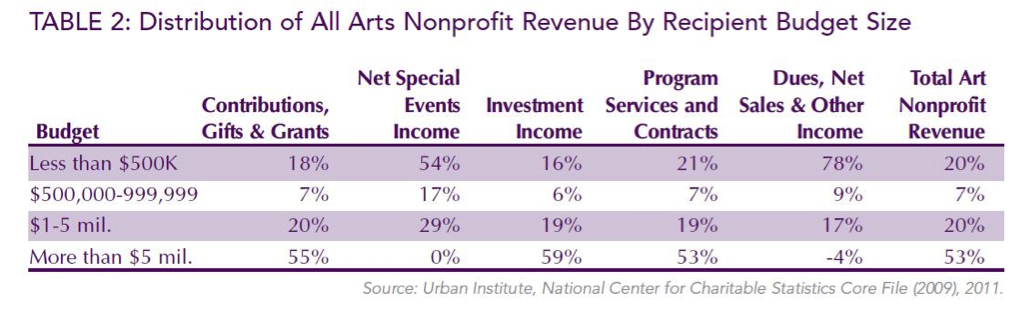

The report’s final case for change revolves around the distribution of funding, pointing to inherent inequities in large, mid-sized and small organizations’ access to private and public capital. According to data from the Urban Institute, organizations with budgets under $500,000 generated 51% of their revenue from contributions, gifts and grants, while the largest nonprofits with budgets over $5 million reported receiving just over 60% of their revenue from such sources:

The disparities appear even greater when looking at how all contributed revenue is distributed across arts organizations of various budget sizes. Only 18% of all contributions, gifts and grants made to arts nonprofits in 2009 went to organizations with budgets less than $500,000, despite the fact that these organizations represent 84% of the total. By contrast, 55% of contributions, gifts and grants go to organizations with budgets more than $5 million. Put another way, organizations that in number represent only 2% of the nonprofit arts sector receive 55% of public and private subsidy:

Sidford suggests that these disparities are likely mirrored individual donor practice, citing a study by The Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University that found more than 70% of highly affluent households gave to the arts in 2009, compared with less than 8% of the general population. Artists and organizations serving marginalized populations, she argues, have more difficulty soliciting individual donations because their constituencies are less able to provide financial contributions. Recent drops in public arts funding (including a 20% decline in local government expenditures on the arts between 2008 and 2010) make circumstances all the more bleak considering that public funding has traditionally been moreaccessible to cultural groups serving marginalized populations. “Shifts in public sector funding,” Sidford writes, “have both immediate and long-term implications for the cultural ecosystem, particularly for the smaller, newer, edgier parts of that system and the artists and groups serving our least advantaged communities.”

Recommendations for Moving Forward

In light of these trends and challenges, “Fusing” asks that arts and culture-focused foundations “make equity a core principle of [their] grantmaking by paying more attention to the people who will benefit from [their] grants and the processes by which the arts and culture provide those benefits.” To assist in this process Sidford provides questions designed to help funders make equity a greater focus in their work. The questions are grouped under five broad purposes for arts philanthropy:

- Sustaining the canons (defined as “important works from established traditions”)

- Nurturing the new (including new artistic works and new audiences for that work)

- Arts education (including media literacy, art appreciation, and advocacy for equity of access to arts education for all children)

- Arts-based community development (“endeavors and organizations that intertwine artistic and community goals”)

- Arts-based economic development (includes arts incubators, spaces for artists, cultural tourism, etc)

The questions under each category focus primarily on diversity (i.e. “Are we recruiting actively applications from artists and organizations working outside the European canon?” “Are artists from diverse cultural backgrounds involved in the programs we fund?”) and breaking down traditional silos between arts and non-arts funding (i.e. “Are we funding both arts and non-arts organizations doing this work?” “Do we recognize art and social change as a form of artmaking?”) “Fusing” concludes by challenging funders to re-examine longstanding assumptions about the role the arts can and do play in our society,“asking, in an authentic way, ‘What is the purpose of philanthropy in the arts today?’”

Analysis

As noted above, “Fusing Arts, Culture and Social Change” was written with the intent of applying the NCRP’s criteria for effective grantmaking to the arts. Those criteria generated a good deal of discussion and controversy when they were released. Members of the philanthropic community, such as then William and Flora Hewlett Foundation President Paul Brest, questioned whether funders should prioritize reducing poverty and discrimination over other social goals such as addressing climate change, pursuing medical breakthroughs, or supporting – you guessed it – the arts. “Fusing” takes NCRP’s criteria for philanthropy, and their underlying premise that serving disadvantaged populations should be a focus for all grantmaking, as a given.

Like the NCRP report, “Fusing” provoked strong and varied reaction across the arts and funding communities (GIA’s online forum on equity in arts funding provides a good sample) when it was originally released. It also provoked a strong and varied reaction in me. Reading it evoked frustration similar to what I feel when I read arts education reports that draw conclusions affirming my fundamental beliefs (i.e. that the arts are a powerful learning tool for children), without providing clear evidence for those conclusions. I understand and support the arguments the reports are trying to make, but wish they did a better job making them.

“Fusing” contains a number of such arguments – about the role of philanthropy and of art in society – that are more values-driven than data-driven. In many cases those values align with my own. I believe, for example, that the arts provide concrete social benefit beyond simple aesthetic pleasure. I believe that all members of our society do not have equal access to that benefit, and that is a problem the private funding community can and should address. “Fusing” does a very good job of affirming those beliefs for me, both by calling attention to organizations doing some very compelling work with arts and social change, and by raising important questions about the extent to which entrenched inequities in early arts philanthropy continue to the present day.

Unfortunately, “Fusing” does not provide a clear vision for how funders should redistribute their resources in response. Two questions loom over the report: 1) in which contexts are the arts the most efficient and effective means of addressing social inequity?, and 2) how can private grant resources most efficiently, effectively and sustainably address inequities within the artistic field?

I don’t think we have concrete answers to either question, and the report muddies the waters further by failing to distinguish consistently between the different segments of the arts sector it identifies as disenfranchised. Specifically, it conflates arts organizations (and individuals) pursuing social justice, arts organizations serving specific non-European ethnic communities, small arts organizations, and individual artists. Clearly, some organizations meet all these descriptors – they are culturally-specific, artist-led, justice-seeking and resource-starved. But rather than keeping consistent focus on the intersection of those qualities, the report treats them somewhat interchangeably. This is more confusing than illuminating, since many small arts organizations, individual artists and culturally-specific organizations have little in common beyond being ignored by mainstream institutional funding.

Collapsing together these segments of the arts sector makes it difficult at times to discern what the report is actually arguing for. For one thing, the report’s data doesn’t clearly align with its recommendations. By emphasizing large organizations’ share of foundation giving, for example, the report implies that funding should be redistributed to small organizations – but never specifically recommends this course of action. For another, its bold but largely unsupported assertions about the role of arts and culture in communities (like “these artists and arts organizations are powerful agents in the struggle for greater fairness and equality”) lump all such entities together without acknowledging their varying levels of quality, capacity, relevance, and impact. As a result, it’s difficult to know which practices deserve greater support, or how to identify them.

Below are some specific ways in which these issues manifest.

The 55%/2% statistic

One of the most jarring (and often cited) statistics from the report is that the “richest” 2% of arts organizations receive 55% of all contributions, gifts and grants made for arts and culture – reminiscent of the “99-percenters versus 1-percenters” divide that fueled the Occupy Wall Street protests this time last year. On the surface it doesn’t seem particularly fair that the largest 2% of organizations would receive the lion’s share of arts funding – but those large organizations tend to have large buildings to maintain, a heck of a lot more people to pay and a broader programming scope. Some of them may be incredibly efficient with the resources they are given, and others may be extremely wasteful – but without considering what their large budgets are being used for, it seems premature to jump to the conclusion that funding a large organization perpetuates inequity.

Moreover, redistributing private grant resources might not even make all that much difference. It’s a common misperception that the 55% number refers just to foundation funding. In fact, it also includes contributions and gifts from individuals, which are actually twice as important as foundation funding for arts organizations in the aggregate. Moreover, according to the report, the proportion of the revenue that large organizations receive from contributions, gifts and grants relative to their budget size (61%) isn’t much different from the proportion received by midsized (59-60%) and even the smallest organizations (51%). Essentially, this statistic is telling us simply that some organizations have larger budgets than others.

That revelation would be more compelling, and provide more cause for alarm, if it were accompanied by findings that culturally-specific organizations tend to receive a proportionally smaller percentage of their grant requests compared to their euro-centric counterparts, or of a substantial inequity in the amount of funding small organizations receive relative to the number of people they serve. But without such context, the most famous number coming out of “Fusing Arts, Culture, and Social Change” is not particularly meaningful.

Capacity and need

”Fusing” argues forcefully that past inequities, in arts funding and beyond, have created a caste system in which organizations that serve marginalized populations are at a disadvantage in obtaining capital relative to established institutions. But “Fusing” presents little evidence that small or mid-sized arts organizations are inherently better equipped to advance social justice than large ones – and that they have a concrete need for more funding in the first place.

Some large arts institutions already spend a substantial amount of money presenting, documenting, conserving and protecting works of art and performance from a wide variety of cultures for the benefit of present and future populations. Others, by virtue of the scope of their work, may be in a much better position to examine themes relevant across cultures, foster dialogue and exchange programs with artists in other parts of the country and the world, and so forth. If funders wanted to influence broad-scale change by reaching a large audience in a short amount of time, large organizations might actually represent an attractive return on investment. A substantial number of them already aim to engage a wide array of audiences, either through targeted outreach activities or by providing free or reduced priced events. For example, well over half of concerts by American orchestras, many of which were the earliest beneficiaries of “elitist” early arts funding practices, are now specifically performed for community engagement or education.

Many programmatic advantages large organizations enjoy are resource-based, of course, and redirecting funding toward small and midsized organizations would obviously allow them to do similar work. Why, however, should we assume that the small and mid-sized organizations would do a better job of advancing social equality if they had more resources? Sidford might argue that culturally-specific and social justice-driven organizations, which are mostly small, would advance equality simply by virtue of their very being. But if the need here is for more culturally-specific, social justice-driven organizations, their numbers appear to already be growing without substantial foundation support. Using the example of the Silicon Valley, Sidford writes, “in 2008, 70 percent of the region’s 659 cultural groups were less than 20 years old, and 30 percent of the new organizations were ethnically-specific… While Silicon Valley may be somewhat ahead of the national demographic curve, related changes are occurring in communities across the country.”

If the number of “artists and tradition bearers” is already on the rise as a natural result of demographic shifts, what additional role is there for private philanthropy to play? Should foundations support these artists and organizations to simply continue doing what they are already doing, or instead ask that they expand or shift their scope? How would the strings (justifiably) attached to traditional grantmaking practice affect what the report implies is a naturally occurring growth in artistic expression and exploration? “Fusing” provides few insights on these important but difficult questions.

Sidford writes,

“activist-artists, tradition bearers, and progressive cultural institutions are using their skills to illuminate our increasing cultural diversity, and to challenge our increasing social, economic and educational divides. They are helping disadvantaged groups give voice to their stories… They are assisting people to exert their political and civil rights… These resources are at every community’s disposal and, with greater philanthropic support, they can be deployed more extensively and effectively” (emphasis mine).

With greater philanthropic support, any resources can be deployed more extensively. Whether or not they are also deployed more effectively, and in particular more effectively than the larger organization down the street, is a different and more complicated question than “Fusing” acknowledges.

None of the issues identified above undermines the assertion that inequities exist within the arts sector. They do, however, raise questions about the extent to which those inequities are problematic, and whether they are problematic for the same reasons that the report identifies.

Implications

“Fusing” does not, in my mind, provide a comprehensive argument for how private grant dollars should be restructured to better address social ills, but where it does succeed is in raising very strong and pointed questions to compel us to think more deeply about how and when the basic notion of equity informs arts funding. What I find to be Sidford’s best and most thought-provoking question isn’t included in “Fusing,” but raised in GIA’s online equity forum: “What if we could start fresh and design a new system of support for arts and culture in this country,” she asks, “with equity as one of its fundamental tenets?”

If “Fusing” had been written as an extended meditation on possible answers to that question, I suspect the resulting essay would envision, among other things, a much greater government investment in the arts. Government institutions in a democratic society are, in theory at least, more naturally aligned toward equitably serving the public, and providing basic services to the disadvantaged, than private institutions. ”Fusing” highlights this point in noting that public arts’ agencies “broad mandate” has historically made their funds more accessible to cultural groups serving marginalized communities. If the demographic and aesthetic statistics in “Fusing” had been applied toward arguing for greater and more stable public investment in the arts, I doubt I would have found as much to quibble with.

Barring a massive reinvestment in public arts funding, which given our current economic and political environment isn’t likely to happen anytime soon, uncertainties remain about how and how much the role of private funders should change. As mentioned earlier, two unanswered questions hover over “Fusing,” both of which have implications for private grantmakers. To revisit them one at a time:

1) In which contexts are the arts are the most efficient and effective means of addressing social inequity?

This question is one that, as a field, we are only beginning to answer. As the report states, “in the past 100 years, we have made a science of developing nonprofit arts institutions but we are still relative neophytes in understanding the role of the arts in catalyzing individual and community capacity, and sustaining individual and community health.” Private funders are well poised to help us deepen that understanding in two ways: first, as “Fusing” suggests, by seeking out and learning from the higher-quality work undertaken by arts and social change organizations; and second, by supporting systems through which our field can become more systematic and thoughtful in exploring and documenting the impact of arts programming on the general public. This latter strategy could take two forms. The first involves incentivizing/requiring grantees to collect more specific information on who their programs are reaching and how exactly those audiences are being served. (The Cultural Data Project springs to mind here as a potential resource with opportunity for expansion.)

The second involves funding third-party research to study both the intended and unexpected consequences of arts programming in underserved communities. Sidford refers to existing research on the impact of art and social change, and implies that established best practices exist (“documented in a growing body of various resources including books, studies, films and websites”). The report doesn’t delve into either in detail, however, so it’s unclear how many models exist and which could (and should) be brought to larger scale. Increased funding for third-party research would be less burdensome to small organizations, which lack infrastructure to support robust research and data collection. It could also help refine best practices and research tools that could then be applied back to large and midsized organizations.

2) How can private grant resources most efficiently, effectively and sustainably address inequities within the artistic field?

The answer(s) to this question will depend in large part on how those inequities are defined. They include inequity of access to artistic and cultural capital, inequity of access to and preservation of cultural heritage, inequity of access to audience, and so forth. If we focus on inequity of benefit from artistic practice, broadly defined, then I think we could use a better understanding of how newer, more grassroots organizations evolve as they expand their scale and scope, both with and without private funding support. Sidford states that “many [such] organizations do not fit the classic model of an arts institution… their internal structures and more informal than conventional arts institutions, their modus operandi more nimble and opportunistic, and their resources almost never in line with their commitments.” As the aforementioned “science” of building nonprofit arts institutions has taught us, organizations undergo fundamental changes in both their administrative structures and their delivery systems as they build up private grant support. These organizations may not now operate under a “classic model,” but the models they do offer seem like fertile testing grounds for better understanding not just the impact of artist-activism, but the impact of private grant support on that activism.

“Fusing Arts, Culture and Social Change” raises compelling questions about inequities in arts and culture funding that demand to be taken seriously. In the end, I cannot dispute the claim that many small and culturally-specific arts organizations deserve to receive more attention and resources than they do. In order to determine how best to identify and support them, however, our field must identify and pursue learning opportunities that can help arts funders be as efficient and impactful with existing resources as possible. As Sidford notes, shifting arts grantmaking toward a greater focus on equity is a long-term process. Managing that shift well requires care, experimentation, and a lot of trial and error. It also requires our collective willingness to set ideology aside and, without apology, question, examine and clarify the benefit and impact of artistic practice on all communities.

FURTHER READING

- Aaron Dorfman, Funding for the Arts Sometimes Benefits All of Us (HuffingtonPost)

- Grantmakers in the Arts’ Online Forum on Equity in Arts Funding

- Janet Brown, It’s a Complex Cultural Eco-System

- Phil Hall, review of Criteria for Philanthropy at Its Best

- Heather Higgins, “The NCRP’s Uncharitable Philanthropic Power” (Forbes.com)

- Niki Jagpal and Kevin Laskowski, “The Philanthropic Landscape: The State of Social Justice Philanthropy”

- Scott Walters, Occupy the Arts

- Diane Ragsdale, The times may be a’changin’ but (no surprise) arts philanthropy ain’t (ArtsJournal)

- Jesse Rosen, New Philanthropy Report Ignores Orchestras’ Service to Communities