As part of our wind-down of Createquity’s work, we’re pleased to offer these parting thoughts for the field of arts research, which based on our observations over a decade of being immersed in the literature. Anyone engaged in arts research will find this article relevant and interesting, but the audiences for whom these recommendations will be most immediately actionable are a) people who commission research (e.g., executives at the National Endowment for the Arts, certain funders like the Surdna, Mellon, and Knight Foundations, and other think tanks and government agencies around the world); and b) people who have autonomy over their own research agenda (e.g., faculty members and graduate students at universities).

A Collective Approach to Building Knowledge

One of the most basic concepts in economics is that of a “public good” – a product or service that does not get “used up” as more and more people use it. Knowledge, by this definition, is pretty much the epitome of a public good – in fact, the more people that use it, the more valuable it arguably becomes.

Sadly, the incentives facing arts researchers push them to operate in silos, sacrificing the efficiency and potential that a more intentional, shared approach would bring. If you’re a researcher who wants to earn a living and you’re not in academia, you’re basically at the mercy of a fragmented market of funder and arts organization clients, most of whom have very parochial concerns and who rarely coordinate with one other on their research goals. In our experience, many of those in a position to commission research at these organizations have limited if any research training themselves, constricting their ability to exercise independent judgment on the best methods and designs for the job in the context of a rapidly evolving profession. Consultants and nonprofits who conduct such research seldom retain much control over the process and deliverable requirements of such efforts, making a centralized and consistent strategy for building knowledge quite difficult to execute. In addition, research contracted as work for hire often carries an implicit or explicit presumption of confidentiality, meaning that some of the most interesting work to understand the field is never made public at all.

College- and university-based researchers may have more autonomy over their portfolios, but face a separate challenge of visibility for their work. In all my years of following and participating in national arts conversations, I have never encountered a single arts funder or non-academic organization leader who makes a practice of reading arts-related research published in academic journals. (This is by no means an arts-specific phenomenon, by the way; a 2007 study estimated that half of all journal articles are only ever read by their authors, editors, and peer reviewers.) And if faculty members want to access funding beyond their internal department or university resources in order to take on larger-scale projects, they are subject to the same warped funding dynamics discussed above and in our previous recommendations piece.

All of these circumstances add up to an intense tragedy of the commons scenario in arts research. Even though research on neglected topics would provide benefits to a widely dispersed audience, it doesn’t happen because no single player is willing to take on the cost and risk of investing in it on their own. As a result, people pay a lot of good money for bad research, and don’t pay money for good research that could be happening instead.

This is not a problem that’s going to be solved overnight, but a clear step in the right direction would be for more convening, collaboration, and coordination between arts researchers, practitioners, and funding bodies. Createquity is not the first to call for such a change, but we see a different path forward than the one past efforts have tried to hew. Historically, the little convening that has taken place among arts researchers has tended toward light-touch facilitation, with no real goal (and thus, no outcome) other than to provide a space to share and learn from one another’s work. While better than nothing, this type of convening is ill suited toward the much more critical (and useful) task of developing a shared research agenda and coordinating a division of labor for the field.

During its life, Createquity offered a demonstration of how one might go about pursuing this latter goal, and we consider that to be one of our organization’s most valuable legacies as we prepare to sunset at the end of this year.

To Get Answers that Mean Something, Ask Questions that Matter

Since Createquity’s relaunch three years ago, the overarching research question driving all of our work has been this one: “what are the most important issues in the arts, and what can we do about them?”

In order to actually answer this, we needed to decide what “importance” means from the perspective of the arts ecosystem. We started off by defining what a healthy arts ecosystem actually looks like, and continued by drawing an equivalence between the cross-disciplinary, holistic concept of wellbeing (or quality of life) and ecosystem health. Doing so enabled us to connect the arts to broader conversations across the social sector about human progress, and create a framework that would make it possible to compare priority areas within the arts against each other. Thus, by 2016, we were describing a healthy arts ecosystem as one in which “the maximum possible collective wellbeing is generated through the arts.” [Note that the use of a term like “maximum possible” is aspirational in the sense that Createquity must make judgments in an environment of significant uncertainty. We aimed with our work to create a fuzzy but fundamentally accurate picture of (a) the world that is and (b) the world that could be with the benefit of different choices.]

With those definitions in hand, we were able to operationalize our tagline as follows:

- “What are the most important issues in the arts?” ➤ “What are the biggest gaps between current conditions and the maximum collective wellbeing that could be generated through the arts?”

- “What can we do about them?” ➤ “For any given gap, what is the most promising strategy or set of strategies available to close it, after taking cost and risk into account?”

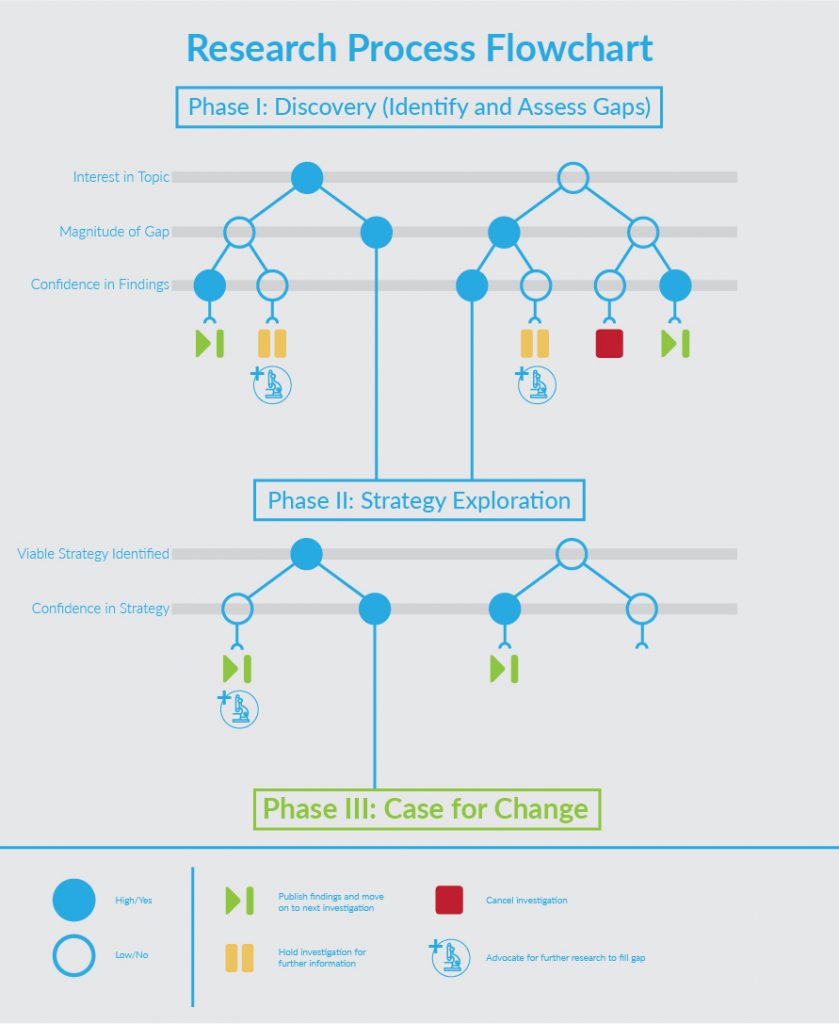

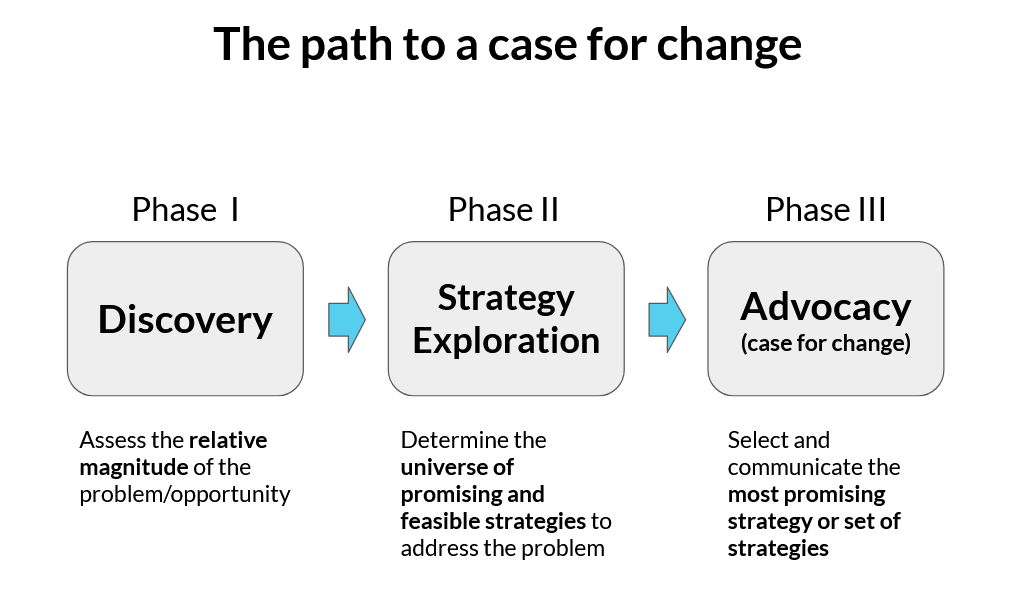

Our research approach placed these questions in the context of a three-phase process, ultimately leading to an advocacy campaign for some kind of concrete change in the sector (what we called a “case for change”):

Phase I, the Discovery Phase, involved examining a wide range of potential problems or opportunities in the arts in order to determine which ones were most pressing from the standpoint of increasing overall quality of life. Each of these gaps between present-day reality and the world that could be was conceived as a separate research investigation. So, many of the big feature articles that you may have read on Createquity, such as Why Don’t They Come?, were the direct result of a Discovery Phase investigation – in that particular case, an exploration of the extent to which socioeconomic disadvantage was interfering with adults’ ability to experience arts and culture as consumers.

Phase I, the Discovery Phase, involved examining a wide range of potential problems or opportunities in the arts in order to determine which ones were most pressing from the standpoint of increasing overall quality of life. Each of these gaps between present-day reality and the world that could be was conceived as a separate research investigation. So, many of the big feature articles that you may have read on Createquity, such as Why Don’t They Come?, were the direct result of a Discovery Phase investigation – in that particular case, an exploration of the extent to which socioeconomic disadvantage was interfering with adults’ ability to experience arts and culture as consumers.

We identified potential investigations through two routes: our own intuitions and experiences, and external input. The latter involved assessing the results of our reader polls, as well as feedback from our advisory council members. By blending these two methods, we could have some assurance that we were investigating issues that our audience cared about, while at the same time not ignoring neglected topics that might not be receiving the attention they deserve.

Each of these investigations involved a thorough review of the evidence in order to estimate as precisely as possible how many people are affected by each issue, by how much, and in what ways. The plan was to then move the most consequential of these issues into the second phase, where we would consider strategies to close the gap between the status quo and the better future that may be possible. Finally, where we’d identified both a significant gap and at least one promising strategy to address it, we’d develop a case for change that translates all of the learning we have undergone into concrete recommendations and calls to action.

In 2014, Createquity buckled down and went to work on the Discovery Phase, hoping to complete our work with a flexible and nimble structure of quasi-volunteers. Unfortunately, this structure proved ill equipped for the significant expenditure of time and mental bandwidth that a systematic evidence review requires, and as a result we were only able to complete a small fraction of our overall Discovery Phase research agenda in the time we had. If funding had been available, we would have pursued the rest of the work using an innovative model called the Synthesis Project.

Borrowing from regranting arrangements often used by foundations and public granting agencies to reach smaller organizations, artists, and communities that they don’t have the capacity to reach directly, the Synthesis Project was a strategy to dramatically scale up Createquity’s Discovery Phase work over a two-year period. In this model, funding and management of research is funneled through one organization which in turn subcontracts individual projects out at market rates to teams of consultants. Instead of one to two research investigations a year, there might then be eight to ten. And instead of multiple agencies managing different timelines and approaches, there would be one centralized agency (in this case, Createquity) coordinating and overseeing all research projects.

The goal of fast-tracking myriad research projects is to build and share knowledge fast enough so that it can be acted upon. This means we aren’t continually stuck in Discovery mode, and instead can move into Strategy and Advocacy phases with a smart prioritization of the relative levels of urgency associated with a wide range of problems and opportunities facing the arts sector. At different key moments, the collective review and reflection on myriad investigations could be used to prioritize areas for further field-wide research and advocacy.

Although Createquity was ultimately unable to transition the Synthesis Project from concept to reality, we still think it’s a great idea, and welcome efforts by others to adapt it in the future. The industry is rich with research that can and should be mined for the gems that will help us to determine where the greatest opportunities lie to advocate for and build a healthier arts ecosystem, and what questions still remain to be answered in order to help us get further along the path toward a case for change.

Specific Gaps in the Literature that We Already Know About

Although we only got through a small portion of our research agenda in the end, it was still enough to identify some glaring gaps in the literature that it would behoove the field to fill as soon as possible:

Arts Participation

From a series of Createquity investigations, we know that many people get their primary cultural fix from things like listening to the music soundtracks of popular TV shows or attending their child’s band rehearsal – activities that do not involve the nonprofit sector at all. The big unanswered question hanging over that observation is this: would nonprofit arts organizations offer a better or more varied type of experience for the people who aren’t currently being reached by them? In other words, does watching a popular television program foster the same benefit to those audience members that attending a live stage play does? And if it does, what is the policy justification for subsidizing the cost of providing the latter, but not the former?

Arts Careers

Much of the evidence currently available on the topic of socioeconomic status and access to arts careers is indirect and based on incomplete data. The vast majority of research on artists’ livelihoods only examines artists’ current socioeconomic status, not their status at the time when they were deciding what career to pursue (and earlier). We thus don’t know much about, for example, the extent to which having rich parents or not affects people’s ability to contemplate pursuing an arts career at all. In addition, we don’t know how the level of intrinsic interest people have in pursuing arts careers might vary across socioeconomic background and other demographic categories, regardless of the reasons.

Cultural Equity

The question mentioned above – how does the level of exposure to and/or interest in arts careers and arts administration jobs differ across race and other demographics (e.g. income, education) – has significant implications for cultural equity advocacy as well. In addition, we don’t know as much as we should about the ingredients of a cultural experience that people find valuable, and whether those ingredients are consistent across demographics. Are the demographics of the staff (artistic, programming, and administrative) and board at arts and cultural organizations predictive of a) the demographics of their participants and b) the quality of experience that participants have? What effect does the scale of an arts organization (or an organization with arts programming) have on its ability to create specific benefits for artists, audiences, and communities of color? Finally, are arts activities designed to combat racism and other forms of oppression effective in that goal, and how do they compare to other anti-oppression strategies?

Benefits of the Arts

Research on the wellbeing effects of the arts could benefit from more longitudinal studies and more experimental and quasi-experimental designs, especially as regards the social and economic impacts of the arts. Even the very best work in this area (e.g., Mark Stern and Susan Seifert’s Social Impact of the Arts Project) still traffics primarily in correlations rather than directly measuring causality. A good example of a study design that takes advantage of a natural experiment is Stephen Sheppard’s analysis of the economic impacts of the opening of MASS MoCA. More generally, it is likely that there is quite a bit of variation in wellbeing effects between disciplines, between different modes of artistic participation (e.g., passive, active, solitary, communal), and between categories of participants. Research syntheses and comparative studies looking specifically at these kinds of differences are generally few and far between.

Organizational Culture

In preparation for awarding of the inaugural Createquity Arts Research Prize, Createquity team members analyzed more than 500 arts research publications released in 2016; a similar process was underway for 2017 research before we made the decision to sunset the operation. An analysis of these publications confirms that very little publicly available research examines one of the most important open questions about the arts ecosystem: what motivates the decisions of donors, funders, and organizations supporting the arts. In particular, to what extent do wealthy individuals disproportionately shape ecosystem outcomes? And how can organizations and donors be incentivized to act in a more ecosystem-serving and wellbeing-maximizing way? We’ve seen a lot of theoretical literature and commentary on this, but very little empirical research, which is a major reason why the 2016 Createquity Arts Research Prize went to Mirae Kim for her work exploring these themes.

Other Observations

In the literature on the benefits of the arts, we very rarely see the impact of grantmakers analyzed as distinct from the impact of programs. When commissioned by grantmakers, such evaluations tend to imply that 100% of the credit for any success can be attributed to the grantmaker’s actions. Yet the truth is that some programs would have happened even without support from that particular grantmaker, and by choosing to spend money on that program the grantmaker is opting not to put that money somewhere else. We’d love to see more sophisticated approaches to determining the real impact of grantmaking decisions, not just the impact of the programs those decisions support.

There are a constellation of suboptimal funding practices in the realm of research and evaluation that deserve close scrutiny. For one thing, the field could benefit from more rationalization between the costs of research (broadly conceived) and the potential value of research. Funders rarely if ever seem to conduct explicit cost-benefit analysis when it comes to arts research. There is actually a methodology to do this that is not that hard to implement in its simplest form. We also strongly recommend against the practice of requiring grantees to demonstrate the impact of the grants they receive without offering to pay the full cost of generating that knowledge. Not only is such a posture unfair to the grantee, it sets up extremely warped incentives if the grantee’s continued funding is contingent upon a good evaluation and the grantee is also responsible for overseeing the evaluation. This would all be made much easier if funders were more willing to make use of existing research on the relevant category of intervention in their strategy design, and evaluate a representative sample of funded projects in the context of judging an overall portfolio rather than assuming an evaluation is needed for each and every investment.

Finally, it would be great to see more international collaboration on arts research. Some of the very best work these days is coming out of the UK, which seems to benefit from a far stronger knowledge infrastructure featuring the likes of NESTA, What Works Wellbeing, and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been contacted in the past couple of years by Canadians eager to learn from their colleagues south of the border. And there are plenty of interesting arts research projects happening all over the world every day.

A Call for Leadership

The arts research field desperately needs a champion to provide leadership and make progress on the issues described above. Although the problems are serious, existing infrastructure like the Cultural Research Network could be leveraged to make progress on shared field goals, like developing a common research agenda, establishing and improving data standards, and co-funding valuable research projects that would be difficult to find a single champion for.

Who might be that champion? Almost anyone could step up to the plate, but in the United States, Grantmakers in the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts are probably the most obvious candidates. Alternatively, this could be a good role for a university entity like Vanderbilt’s Curb Center, SMU’s National Center for Arts Research, or Virginia Commonwealth University’s Arts Research Institute. We know that in Canada, an organization called Mass Culture is attempting to play this role, and additional policy and research efforts are underway at the Banff Centre.

Research can help us do our jobs better and make the world a more exciting, loving, and equitable place, but only if we give it the time and resources it needs. The infrastructure for building and spreading knowledge in the arts sector has long been under strain, if not entirely broken. But another world is indeed possible, and here we’ve tried to lay out the first steps toward making it a reality. The good people who work day in and day out to create experiences to cherish for a lifetime, and those who ultimately benefit from that programming, deserve nothing less.

Thanks to Rebecca Ratzkin for her contributions to this article.