Take a listen to Voice 1:

In the past fifteen years, the number of nonprofit theater companies in the United States has doubled while audiences and funding have shrunk. Neither the field nor the next generation of artists is served by this unexamined multiplication…There has been tremendous collective buy-in to what has become a fossilized model.

—Rebecca Novick, theater director and arts consultant

Then hear out Voice 2:

We communities of color are still trying to understand the mainstream nonprofit culture, with all its unwritten rules and regulations. We are trying to be better nonprofit players. We have to, because the game is not going to change any time soon, and those communities who don’t know the rules or who don’t practice enough are left behind… We have no choice.

—Vu Le, executive director of Rainier Valley Corps

Stop and reflect on Voice 3:

I’ve always been a bit uncomfortable with our sector’s be-all-and-end-all focus on the needs of the nonprofit arts… The sector has grown bigger without getting richer.

—Bill Ivey, former chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts

See if you agree with Voice 4:

Funding organizations really do roll their eyes these days, when yet another nonprofit, pops up with its hands out. Reality: no one is gonna pay your tab.

—Misha Penton, opera singer, theater artist, and artistic director of Divergence Vocal Theater

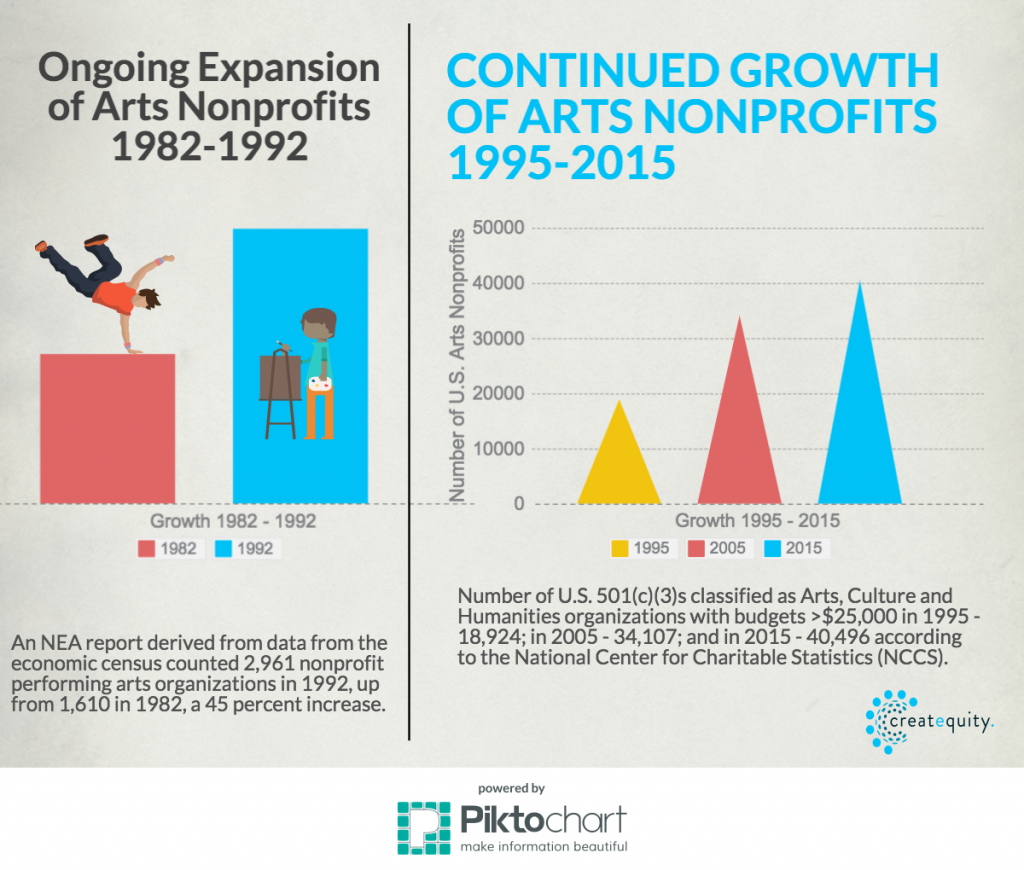

Opinions about the nonprofit arts model—the fundamental legal and business structure in which arts nonprofits in the United States work—are as numerous and varied as 501(c)(3)s themselves. But one thing all of these quotes take for granted is the existence of the model itself. While that system may seem “fossilized” to some, the truth is that most arts nonprofits today are younger than most of our parents. The boom of arts nonprofits has been a relatively recent phenomenon, and it came about thanks in large part to a handful of individuals who intentionally put it into motion.

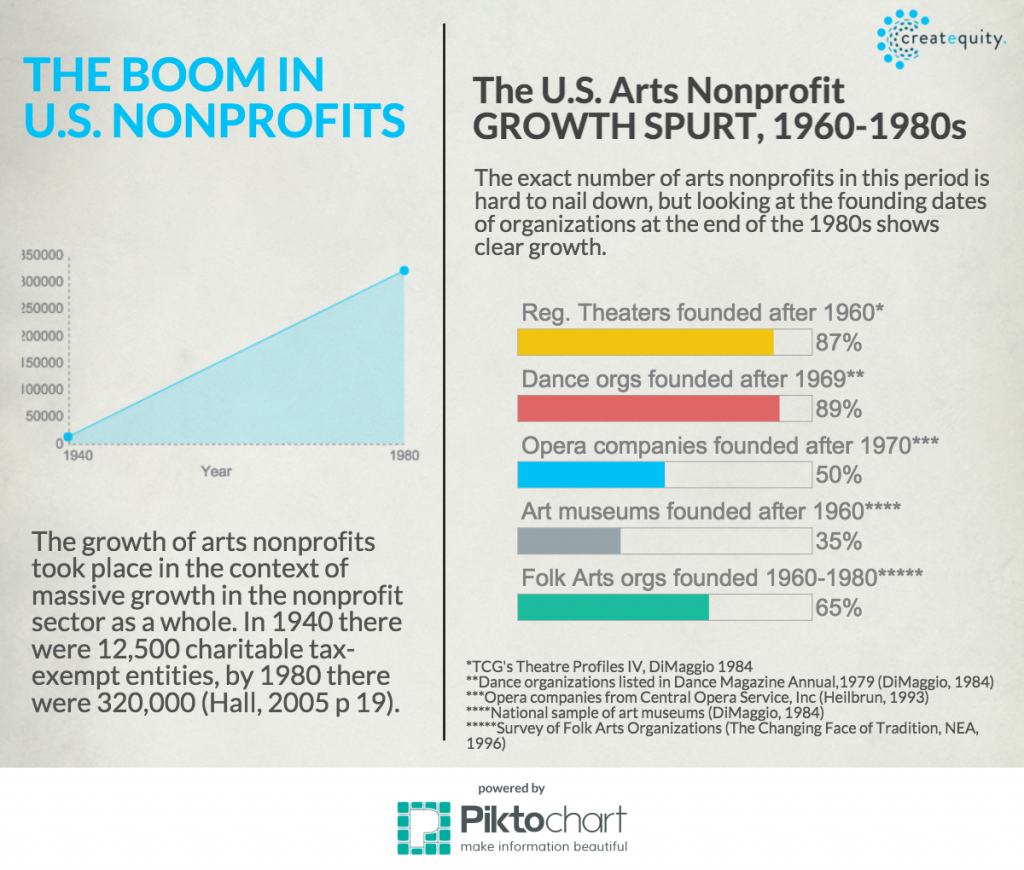

Graphic by Shawn Lent and Katherine Ingersoll for Createquity. See endnotes for additional detail on sourcing.

The story of the nonprofit model is part of the broader heritage of nonprofits, and follows a similar trajectory. A combination of intentional interventions and societal factors led to a massive expansion of the nonprofit sector in the United States in the middle of the 20th century, both in terms of size and portion of overall economic activity. Nonprofit expenses and assets actually outpaced the economy between 1994 and 2004 primarily thanks to the growth of hospitals, health organizations and private colleges. In 2012, there was 1 nonprofit for every 175 Americans.

Despite such a boom, life inside the current arts ecosystem is not all it could be. Createquity’s mission is to identify the most important issues in the arts and what we can do about them, but a crucial barrier to executing on that premise is the sector’s limited capacity to create change. While the 501(c)(3) arts model offers infrastructure that, in theory, combines artistic aspiration with public accountability, the decentralization and limited scope of government policy make large-scale, systemic change in the sector difficult to accomplish. Yet Createquity’s long-range goal is to do exactly that, or at the very least to catalyze it.

One of the things that I pray for is that people with power will get good sense, and that people with good sense will get power…

—Dixie Carter as Julia Sugarbaker

To accurately predict how change can happen in the arts ecosystem, it would help to understand how change has already taken place in our arts 501(c)(3) genealogy. Specifically, we want to know whether individuals or organizations can truly and intentionally marshal change, or if a cloudy mix of circumstances is responsible for where we are today. Has transformation in the arts sector historically been calculated and choreographed, or organic and inadvertent?

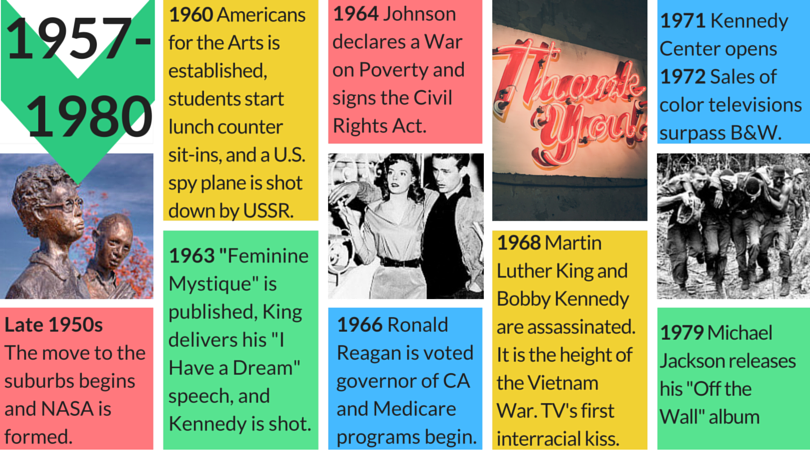

It turns out that a narrow time period starting in the mid-1950s and ending in the late 1970s presents clear examples of deliberate and broad action, precipitating one of the most extensive changes in the arts ecosystem: the spread and embrace of the nonprofit model as a mechanism for cultivating and promoting the arts and culture within the United States.

But first, some time travel is in order.

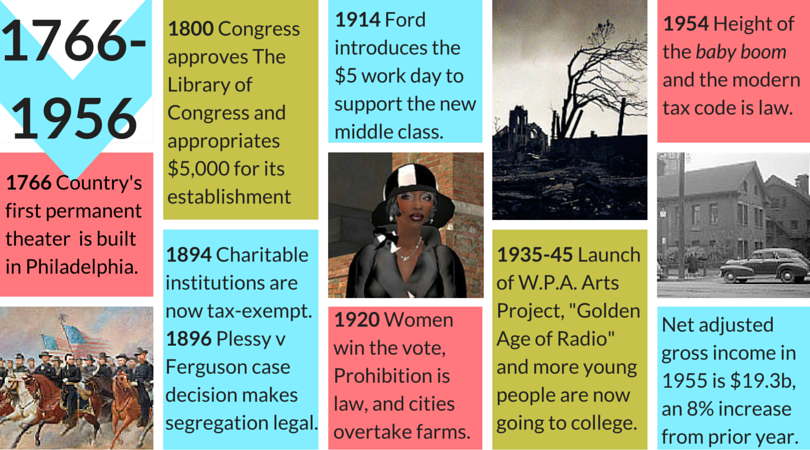

THE ARTS ECOSYSTEM’S EARLY DAYS

The modern tax code, including the arts 501(c)(3) status we know today, was established in 1954, but its roots stretch back much farther. Several of our nation’s first theaters and museums were built before the American Revolution, but voluntary associations in this colonial period (as well as in the freshly independent years following the war) were limited by the strong role of the church and emboldened by the lack of federal authority over them. The landmark 1819 Supreme Court decision of Trustees of Dartmouth College vs. Woodward further constrained the government’s power to intervene in private charitable organizations and set protection for incorporated endowments, including the few for arts institutions.

From the Met to the Hull House, arts participation in 19th century America was shaped by class division. Urban wealthy elites, their formal governing sway slipping away in a democratic society, established private organizations to advance the greater good—and to preserve their class status. In the wake of civil war and the arrival of nearly 12 million immigrants, Americans formed mutual aid societies and unions, but also private schools, libraries, social clubs, and a scattering of non-commercial museums and symphony orchestras.

Donations from wealthy individuals were the most important source of support, and policymakers in the late 1800s introduced the country’s first statutory references and implementation of tax exemption for charitable organizations. In 1889, a certain Mr. Andrew Carnegie published “Wealth,” an essay pressing other tycoons to join him in donating considerable percentages of their fortunes for the good of society, including the arts and humanities. Years later, historians would credit Carnegie with conceptualizing what is now the modern philanthropic foundation.

Even so, through the rip-roaring early part of the 20th century, the dominant vehicle for performing arts enterprises, from jazz clubs to theater ensembles, was the commercial sole proprietorship. As the socioeconomic gap became a socioeconomic crater, philanthropic support for arts nonprofits remained limited and highly localized. Coming out of the Great Depression and WWII, national foundations like Carnegie’s were primarily setting their sights on educational goals.

All the while, countless early arts pioneers, renegades, and boat rockers had the ambition to innovate on the local level, and many eventually saw the fruits of their efforts spread to varying degrees. But it wasn’t until the middle of the 20th century that the stage was set for sweeping transformation for the arts at the national level.

A MAN ON A MISSION

There are people who more than others constantly see themselves between past and future, …both in their own lives and in the history of mankind. And I’m one of those persons.

In the early 1950s, an executive named William McPeak participated in a study group for the Ford Foundation, which was exploring potential new structures and priorities as it prepared to become the largest foundation in the world. McPeak was pushing Ford to include the humanities in its vision for the future. One of his confidants during that struggle was W. McNeil “Mac” Lowry, a civilian journalist with the Washington bureau of Cox Newspapers who had been McPeak’s colleague at the Office of Wartime Information. Ford ultimately decided against funding the humanities when it expanded its scope from serving Detroit to focusing on social justice nationally and internationally, moving its office to New York City, but McPeak was hired as Ford’s Associate Director in 1953 and he brought Lowry on board as his assistant.

Two years into his tenure, Lowry was promoted to Program Director for Education and started suggesting ad hoc humanities grants under this education arm. They were small and few, and they were accepted. He also began writing policy papers and advocating internally for the creation of a large, full-fledged arts and humanities funding arm. This proposal was bold and unprecedented for any foundation at the time. With persistence and McPeak’s partnership, a mere four years after joining the foundation, Lowry was named director of its newly minted Division of Humanities and the Arts.

Lowry aimed to leverage Ford’s dollars and influence toward a grand vision of a robust arts field across the United States, but he started with a more tangible and comprehensible project: an inventory of the field conducted through interviews with artists and arts stakeholders, which would subsequently inform the decision on the part of Ford’s trustees whether to make the program permanent.

Lowry knew that his audience didn’t initially take his project very seriously. But as his assistant Marcia Thompson put it, it quickly became clear that the trustees “were not only entertained but were enormously interested in the field.” Lowry later said of his thinking,

It was not any secret to me what the little start of that program in 1957 might mean on a national basis… It’s just, you couldn’t divulge it because it was still dream and plan… This work is… a little bit like casting a stone in a puddle, but precisely which stone and precisely which puddle and for precisely which effect [is] the real creative part of it.

He and Thompson began by giving themselves the task of creating a directory with the names and contact information of every art critic and artist they could find around the country. Long before digital spreadsheets or the Internet, this was a hefty self-assignment. A former journalist with a history of telling it like it is, Lowry was willing to question loyalties and cliques. For example, he worked to extend professional arts opportunities outside major metropolitan areas even though several Ford trustees with connections to prominent New York institutions pushed back. He, along with associate director Edward F. D’Arms, traveled the country to speak with artists and stakeholders at over 175 arts companies. Lowry’s was a personal approach which gave him strong buy-in and trust from people who were actually engaged in arts work; he preferred direct correspondence with prospective grantees, including the likes of James Baldwin and Tom Stoppard. Lowry synthesized this mountain of data with more formal knowledge from economics and policy to begin to design the functions of Ford’s arts program.

Choosing to start with theater as his first arts discipline, Lowry used his new directory to send out a wide call for proposals, looking for groups (many of which were either sole proprietorships or amateur projects at the time) that seemed ready for the next step in professionalization. The focus was on smaller organizations outside the big cities because he did not want to see “money that could go to artists and artistic directors or to their outlets put in bricks and mortar.” With an investment of $9 million in 1961, the Ford Foundation had gathered steam for what would become the regional theater movement. After seven years of commercial operation, Zelda Fichandler transformed DC’s Arena Stage into one of the country’s first nonprofit theaters, primarily to receive a grant from the Ford Foundation.

One of Lowry’s primary aims was to increase the amount of professional performing arts activity in the country, but he wanted to be inclusive whenever possible. He had intended to fund a black theater when he launched the program in 1957 but was unable to locate a promising black artistic director able to get a new theater up and running. A couple years after Martin Luther King Jr. inspired the country with his dream of integration, a playwright named Douglas Turner Ward wrote an editorial in the New York Times about the need for a black theater, supporting disenfranchised artists, managers, writers, and designers. Lowry read the article and contacted Ward immediately. Shortly after, with a Ford grant of $434,000 ($3.3 million in 2016 dollars), Ward, producer/actor Robert Hooks and theater manager Gerald Krone would establish the Negro Ensemble Theatre Company in 1965.

Lowry got artists out of their comfort zones and towards professionalization, and was well aware of the consequences of him doing so. As he describes it,

[artistic producers] had to think about ‘where does this move us to the next phase?’…They took on costly activities that they had ignored before…. So they were stretched. And some of them were even shrewd enough to say in advance of a grant, ‘You’re going to stretch me, aren’t you?’ I’d say, ‘Yes, I’m sorry, that’s an inevitable consequence of this.’”

Under his direction, arts grants now required matching dollars for the first time and arts grantees were pushed to improve their marketing practices. For example, he directly supported Danny Newman, the press agent at Chicago Lyric Opera, to evangelize the subscription model to performing arts organizations across the country.

Lowry’s legacy also stretched entire segments of the performing arts. During his tenure, Ford invested $19.5 million to help build 17 resident professional theaters between 1962 and 1976, and was the first American foundation to fund dance on a large scale ($22.5 million from 1957-1973). Ford’s largest arts investment over this time was the Symphony Orchestra Program ($80.2 million). Lowry retired from his position as Vice President at Ford in 1974, and passed away in 1993.

Mac Lowry could easily be labeled one of the nonprofit arts sector’s most significant figures of all time. No exaggeration. Lincoln Kirstein, co-founder of the New York City Ballet, described Lowry as “the single most influential patron of the performing arts that the American democratic system has produced.” By changing the financial incentives for artists, he directly helped to create an entire field of professional, nonprofit performing arts institutions. Thanks to Lowry, Ford became not only the first foundation to fund arts institutions on a large scale (making $249.8 million worth of arts grants 1957-1973, or nearly $2 billion in today’s dollars), but also the largest nongovernmental funder of the nonprofit performing arts.

In this position, the Ford Foundation was able to exert considerable influence on the sector. Bill Ivey notes that “the ‘Ford model’ remains the gold standard shaping intervention in America’s arts system.” Decades later, Ford is 5th on a list of the top 25 arts funders, which underscores how the number of foundations interested in the arts has grown over time, and the strength of Lowry’s legacy in philanthropy.

At the Ford Foundation, Lowry had been given wide latitude to try new things, with a significant amount of money. His success had always been boosted by internal support from McPeak, but in 1966 Ford welcomed one of its more liberal presidents, McGeorge Bundy, who came to Ford from the Johnson administration and his “Great Society” programs. Under Bundy’s leadership, Ford was an instigator of public-private philanthropy and Lowry was able to connect to the subsidy argument of federal support for the arts. Lowry later reflected that “a pervasive effect of the Ford program was the enlightenment that began to spread not only about the importance of nonprofit artistic enterprises, but more precisely their justification for subsidy.”

Lowry and his colleagues were able to ride a wave of public support and concern while acknowledging and working with, not against, broader political agendas. To Createquity, this insight seems critical to understanding why monumental change could take place when it did, and it raises the question of how such transformation could be possible in our current polarized political climate.

THREE ARTS PRESIDENTS AND A NANCY

With standoffs with Vladimir Putin and strikes at orchestras, theaters and beyond dominating modern newsfeeds, it is difficult to imagine a contemporary POTUS declaring the arts as a diplomatic weapon against Russia or sending the Secretary of Labor to personally mediate a dispute between a major arts institution and its workers. Yet in the late 1950s and early 1960s, that is exactly what happened.

As Lowry’s influence at Ford evolved, so did the operative role of the federal government in the arts. President Eisenhower, a Republican, advocated in his 1955 State of the Union address for the establishment of a Federal Advisory Commission on the Arts. This was cultural cold war: as one artistic director put it, “Eisenhower spoke of a lack of achievement in the cultural sphere: Who did we have to export in terms of ballet, opera and theatre companies? How could we compete with Russia, which had such a rich cultural spectrum of performing arts?”

Although Eisenhower was all talk and little action on the arts and no formal advisory body was created during his two terms, he did have one major accomplishment: the passing of the National Cultural Center Act of Congress in 1958, which would set the stage for the founding of a certain, prominent national performing arts center on the Potomac River thirteen years later.

Two years later, John F. Kennedy won the election with a party platform that included a brief mention of “a federal advisory agency to assist in the evaluation, development, and expansion of cultural resources.” Although he didn’t have a cultural agenda, the Kennedy Administration would be the one to finally elevate cultural policy to a national priority.

During his first year as President, Kennedy had the White House taking direct action in the arts. When the American Federation of Musicians Local 802 led a strike against The Metropolitan Opera during his first year in office, Kennedy sent Secretary of Labor Arthur Goldberg to arbitrate the salary dispute that had halted the current production season. While serving as the mediator in his office, Goldberg suggested that government funds be used to help settle the Met’s $840,000 debt (that would be more than $6.6 million federal dollars today used to bail out a private arts institution); it’s a safe bet today’s Congress would not get behind that.

Possibly influenced by Jacqueline Kennedy’s love for the arts, President Kennedy expanded his public support, saying, “The life of the arts, far from being an interruption, a distraction, in the life of a nation, is very close to the center of a nation’s purpose . . . and is a test of the quality of a nation’s civilization.” In contrast to Eisenhower’s cold war logic, Kennedy’s policy vision would position arts and culture as sources of national hope and solidarity, continuing to push toward both a national center and a federal agency for arts and culture.

President Kennedy was active in the arts right up until his shocking murder in Dallas. In 1963 alone, he emphasized the importance of national recognition of the arts in a speech at the dedication of the Robert Frost Library at Amherst College; established the Advisory Council on the Arts (not appointed until after his death); and commissioned a report by August Heckscher, director of the Twentieth Century Fund and his special consultant for the arts, on the relationship between the arts and the Federal government.

Together, these resources laid the foundation for the ultimate achievement in linking federal government to arts and culture, the signing of the National Endowment for the Arts and National Endowment for the Humanities into law in 1965 by President Lyndon Baines Johnson. Johnson chose Roger Lacey Stevens, a Broadway producer who had led the fundraising efforts for the National Cultural Center (later renamed The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts), as the NEA’s first Chairman and Special Assistant on the Arts.

NEH Chairman William Adams tours the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library exhibits – photo by the LBJ Foundation on flickr

Following Stevens’s brief inaugural tenure as NEA Chairman, Nancy Hanks (not the mother of the 16th President of the United States, for whom she is descended and named), was selected to head the search for his successor. After several prominent figures had turned the position down, Hanks herself was appointed by President Nixon in 1969; according to Stevens, “they were looking for some women for jobs.” She was a Southern Republican and a Duke University graduate who began her career as a DC receptionist and later gained White House experience as assistant to Nelson A. Rockefeller and his arts programs. Afterward, while on staff at The Rockefeller Brothers Fund, Hanks published the influential report, The Performing Arts: Problems & Prospects (1965). By the end of the 1960s, she had both been named president of the Associated Council on the Arts (ACA) and diagnosed with cancer. She chose to remain unmarried and without children; she would later be deemed the mother of a million artists.

Amidst the burgeoning feminist movement, Hanks took the reins of a then-nascent NEA with grander aims for the agency. In her first six weeks at the helm of the NEA, she personally spoke to 200 Congressmen to advocate for her proposal to double the budget and to secure future appropriations for the nation’s bicentennial, which was more than six years ahead. Hanks was a sagacious power; her office became a lobbying machine.

She battled her cancer quietly while strongarming Congress, protecting NEA political territory, and preempting controversies for the agency. In 1970, when the NEA budget faced the ax, Hanks and her assistant individually cornered over 100 Congressmen and succeeded in swaying their votes. Julia Butler Hansen, a Democrat from Washington State and chairwoman of the House appropriations subcommittee during that term, said she needed to see letters from constituents to be convinced, so Hanks somehow got a form letter onto every theater seat in the country and, within a few weeks, had thousands of them into Hansen’s mailbox. When artists won prestigious prizes, Hanks would send out letters to the Representatives of their home states, reminding them that “good artists do not just happen.”

Hanks put a large emphasis on grants to institutions, which helped to make arts funding a bipartisan issue since many wealthy board members of symphonies and museums were Republicans like her. The concept of public subsidy for the arts was sold as a cure for the “cost disease” endemic to nonprofit arts organizations. Revenue and private donations alone could not support the sector, she believed; the income gap must be filled.

With an art-for-all-Americans ethos, Hanks supported a plentitude of smaller nonprofit arts organizations in newly funded areas such as crafts. Additionally, Hanks played an instrumental role in establishing the Arts Council of Americas to unite the more than 50 community arts councils already in existence and in expanding the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies in order to have a well-funded state council in every state and territory in the U.S. Much of the NEA’s funding was designated to run through these state councils.

Later in her tenure Hanks authorized the NEA Challenge Grants, which demanded matching contributions to leverage investment from the private sector. This was a strategy similar to those of the Ford Foundation in the 1960s and the Johnson Administration’s War on Poverty.

Before Hanks, the NEA was more of a figurehead organization with a modest budget; by 1976, it was the largest institutional funder of the arts in the country. In brief, she was the savviest operator in the NEA’s history. She served two terms as the NEA chair until her resignation in 1977, and she died of her cancer six years later at age 55. A mere three weeks after her passing, President Reagan (whose economic policies were threatening the existence of the NEA and NEH at the time) signed a law renaming NEA and NEH’s erstwhile home, the Old Post Office, in Washington, D.C. the Nancy Hanks Center.

HOW LOWRY AND HANKS CHANGED THE ARTS NONPROFIT SECTOR FOREVER

Neither Lowry nor Hanks saw themselves as artists (Hanks said her only art form was “needlepoint typewriter covers”; others said that it clearly persuasion), yet both were passionate in building towards a new arts vision for America, supporting and connecting artists nationwide. They were willing to defy the expectations and design of their jobs in order to create financial and structural support for artists. Both traveled the country for the cause; Lowry to discover promising artistic directors, and Hanks to advocate on their behalf.

Their combined legacy was to establish the current shape of the nonprofit arts sector and its mechanisms of funding. Importantly, both the Ford Foundation and the federal government brought vast new resources to the arts funding table, and directed those resources almost exclusively to nonprofit arts organizations. In doing so, not only did Lowry and Hanks catalyze the arts 501(c)(3) boom, they created the common practice of matching grants, the growth and coordination of local arts agencies, the use of grant panels, the rise of grantwriter-as-paid-employee in arts institution, and more. The influence of each can be seen in the geographic spread of infrastructure to support the arts across the country — regional theaters, dance companies, and symphony orchestras in Lowry’s case, and arts councils in Hanks’s.

They engineered the initial professionalization of the field. Publications and conferences, like those of the Theatre Communications Group which Lowry first convened, declared and disseminated best practices. The effect of these deliberate acts was characteristic of the organizational ecology concept of “legitimation”: as a particular type of organization becomes more accepted, it is established more and more frequently. By the mid-1970s, the nonprofit was set as the expected and dominant legal structure for new arts organizations.

We approached this research wanting to learn how change happens; we didn’t intend to dwell on whether the change has been good or bad. That said, there are several aspects of the arts ecosystem in America today that seem to have been shaped by from the transformation fostered by Lowry, Hanks, Kennedy, and others in the middle of the 20th century.

There is more, more, more

The timing of the boom differed by discipline, but all disciplines saw sustained growth when they began to embrace the nonprofit structure. Overall, despite government funding cuts, Reaganomics and the culture wars, the leveling of private funding, and periodic recessions since the 1980-90s, the number of arts nonprofit organizations has shown continued, though slowing, growth.

What does that growth tell us about the number of people being served by these organizations, or about the amount of art available in general? We know that as the nonprofit arts sector grows it employs more individuals; however, it is unclear whether more artists are getting paid to make art, or if there are more opportunities for artists to work as administrators, or whether more money is going to hire arts managers and educators.

Did the increase in the number of arts organizations contribute to higher levels of arts attendance? Several reports show increased activity in certain disciplines during the 1960-1980s, but it is unclear whether the number of arts products/activities actually increased, or if it was just that more arts experiences were made professional or formal in ways that allowed them to be counted.

What we do know is that as the growth of the sector appears to have yielded more opportunities and inclination for people to experience the arts. For example, there have been rising rates of spending on arts experiences in relation to total leisure spending, which can be attributed to the fact that increased institutional grant support opened up new markets.

Opportunities for (nonprofit) arts participation are available across the country

Before Lowry and Hanks, almost all professional performing arts companies were in New York City and other metropolitan hubs on the East Coast, but the geographic spread of institutional funding starting in the 1960s has supplied arts, especially performing arts, outside of major metropolises into towns where the arts are not as commercially viable. During Hanks’s tenure, NEA grants found their way into all 50 states and six U.S. territories. Analysis by the NEA performed in both 1982 and 1992 on the division between nonprofit and commercial performing arts companies showed that nonprofit organizations represented higher percentages of the sector in areas that were not centers for commercial performance.

American art is now much more than Eurocentric symphonies, museums and theaters

The notion that we should remove barriers to access of the arts is now widely accepted and seems to be a legacy of Hanks’s ethos. During the 1970s-1990s, the boomers worked to democratize the arts: careers, patronage and participation. The sector’s expansion started in the professional performing arts but then grew to support a broader range of genres and disciplines, and it’s likely that this has made a stronger mix of cultural products available to society today. Although Lowry’s early efforts were focused on professional theater, music, and dance, once the funding infrastructure was in place and the category of nonprofit arts was established, the momentum provided by the new structures and incentives fostered demands to support other artistic disciplines, and, later, the inclusion of a broader range of artistic endeavors.

The U.S. arts ecosystem is still striving for equity

Although more resources are available to support cultural activity since before the nonprofit arts sector boom, the nonprofit system seems to have benefited European cultural traditions more than others, and white artists more than artists of color. It has legitimately been observed that arts genres that have been accepted as high culture for longer periods have adopted the nonprofit form in greater numbers, whereas cultural forms that have more recently come to be seen as important have been more likely to be commercial. In 1979, only 4% of NEA grant funds were going to black arts organizations, almost exclusively through its Expansion Arts initiative. In 1994, Elizabeth Broun, director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American Art, was appalled to realize that “for 135 years after the founding of the federal art collections in 1829, no work by a black American was represented in the nation’s holdings.”

It seems that movement toward true equity in the nonprofit arts sector has been weak, slow, incomplete, or put in the hands of large institutions as part a community engagement trickle-down scenario. Issues of equity in funding, leadership and audiences by race, gender, disability, etc. have manifested differently in different disciplines, but important questions linger on whether the growth of the nonprofit sector has brought with it a growth of inequality.

WHERE WE GO FROM HERE

The story of Lowry and Hanks is the story of the establishment. They were two individuals who, welcomed into institutions of wealth, power, and (white privilege), adroitly navigated those spaces in a mission to do good across the arts sector. Yet as more and more arts nonprofits sprung up over generations, the metrics they established spread like a gospel of the arts, not recognizing the full array of cultural expression people were already employing. It seems safe to assume that white cultural traditions were more robustly promoted and supported by Lowry, Hanks and their allies, which is why it is important to note other schismatics who were integral to further developing and supporting the arts, to problematizing the relationship between nonprofit and commercial artmaking, to diversifying access and opportunity in the field, to utilizing technology, and to increasing popularity and new audiences for the arts. Influencers and moments of change like these will be explored in upcoming Createquity features.

Many of the sector’s successes, as well as its intractable issues, stem from the dominance of the nonprofit arts model which was driven by those formative actions in the 1950s-1960s. Lowry and his peers deliberately sought to create a healthier arts ecosystem by strengthening and professionalizing arts institutions. Yet the question is worth asking whether most institutions, thus professionalized, tend to prioritize their own preservation. Createquity’s definition of a healthy arts ecosystem asserts that “To the extent that any element within the infrastructure is unwilling or unable to put the goal of improving people’s lives in concrete and meaningful ways first, it’s acting as a drag on the system’s capacity to change for the better. We see this problem manifesting in a number of ways, including the reluctance of cultural institutions to prioritize the interests of the ecosystem as a whole ahead of their own prosperity…” Will future changemakers be the ones who, like Lowry, are able to prioritize the entire arts ecosystem over their own institutions?

This is just the first of many articles on the capacity to create change in the arts ecosystem. We invite you to get involved in this journey by joining us for a #CreatequityAsks Twitter chat on how change happens on March 17th from 7:30-8:30pm Eastern.

Add to Calendar: Outlook – Google – Yahoo – Outlook.com – Apple Calendar