SUMMARY:

- A large and emerging literature on the topic of wellbeing has a lot to teach us about the arts’ role in society.

- Wellbeing is a way of grouping the various components of individual and societal health under a single conceptual umbrella. This is important because it opens up the possibility of understanding the relative value or benefit of those components as part of an integrated whole instead of treating them as completely separate.

- A number of large-scale international economic and social policy initiatives are grounded in wellbeing, including much of the global development work undertaken by the United Nations.

- Most wellbeing definitions do not explicitly include culture, but some do. In particular, a variation of a wellbeing framework called the capability approach recognizes the capacity for imagination and play as critical components of human wellbeing.

- Describing the benefits and costs of arts ecosystem outcomes in the language of wellbeing could earn the field a proper seat at the table in conversations about human progress without downplaying the so-called “intrinsic” benefits of the arts.

* * *

Quick! What’s the most important issue in the arts? Is it declining audiences? The fact that it’s so hard to make a living as an artist? Changing demographics and cultural equity? Unsustainable business models? New technologies? Government funding? Arts education? Gentrification? Creative placemaking? Where I can go to figure out what the heck I’m doing this Friday night?

Spend any time reading up on arts policy and philanthropy or attending conferences in the arts, and you’ll see plenty of attention devoted to all of these topics and more. To be sure, all of them have implications for the future of arts and culture in the United States, not to mention the rest of the world. The challenge is, with so many issues to track, and no way of comparing them to each other, we can’t know how to prioritize our limited energies in the areas that are going to make the most difference. We can’t even be sure that the biggest problems or opportunities in the sector are on our collective radar at all. What if the most impactful thing we could do is something that no one’s talking about?

At Createquity, we are trying to tackle that conundrum head-on by framing our work in terms of the broad language of social good and human progress. In this way we sometimes think of ourselves as a cause-specific analogue to the effective altruism movement, which tries to identify the highest-leverage opportunities to do the most good with the resources available to us, whatever they might be. Accordingly, when we developed our definition of a healthy arts ecosystem, we declared that all of the conditions and outcomes named in that definition should be understood in the broader context of “improving people’s lives in concrete and meaningful ways.” While that names a single yardstick of “life improvement” to measure every success against, without further elaborating on what it actually means to improve someone’s life, the concept is not very useful in practice. Fortunately, many smart people have been grappling with the same problem and have made significant strides towards adding specificity around such terms in recent decades. Our investigation of their work has led us to an exciting and emerging literature on the topic of wellbeing, a literature with roots in multiple fields outside of the arts.

WELLBEING 101

While no consensus definition of wellbeing exists, broadly speaking, it is a way of holistically grouping the many components of individual and societal health under a single conceptual umbrella. The intellectual origins of wellbeing date back more than half a century to 1948, when the World Health Organization framed its definition of health not only in terms of the absence of troublesome physical symptoms, but also in terms of the presence of certain attributes that suggested “physical, mental, and social well-being.” This was a departure from the prevalent medical conception of health at the time, which narrowly focused on the presence or absence of disease and categories of ailments in individuals.

Before long, this holistic perspective began to infiltrate the study of whole communities and societies. An early theoretical work on “social indicators” in the United States was undertaken by Harvard Business School professor Raymond Bauer in the mid-1960s and sponsored (surprisingly enough) by NASA. With a large and visible public investment to protect, the space agency asked Bauer to quantify its effects on American life, but the professor concluded that the effort would not get far without an established way to quantify improvements to social conditions. To bridge that gap, Bauer and his co-authors pioneered the idea and early methods of developing statistical measures of social values and goals.

Bauer’s work coincided with a growing backlash against the then-commonplace use of economic measures such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to measure social progress in the national and international policy arena. While GDP is a broadly accepted way to measure the size of an economy, it is at best a flawed proxy for the outcomes that really signify how well societies are faring. In one of the more remarkable developments in the history of political economy, the teenage King Jigme Wangchuk of the small nation of Bhutan coined the term “Gross National Happiness” as a replacement for GDP in 1972. (Decades later, a fleshed-out version of GNH is in active use in the country and enshrined in its Constitution.) Around the same time, Richard Easterlin’s research on happiness levels in post-war Europe in suggested that increased material abundance did not necessarily yield increased happiness, which helped launch the field of happiness economics. By 2008, when the French government brought together a star-studded international panel of economists led by Nobel Prize winners Joseph E. Stiglitz and Amartya Sen to try to move beyond GDP once and for all, wellbeing was rapidly establishing itself as the dominant theoretical foundation of the global policy arena. The resulting Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi Commission report is considered a major watershed in the mainstreaming of wellbeing.

Today, a large and growing field of study is devoted to wellbeing and its measurement, with its own peer-reviewed journals, leading experts, and esoteric controversies. Given that wellbeing scholars operate at the intersection of a number of different fields, it’s not surprising that the lexicon can sometimes get messy, with terms such as quality of life, standard of living, and livability variously standing in for the idea of a holistic measure of individual and community health. One of the more notable debates has centered around objective vs. subjective ways of conceptualizing wellbeing. Historically, a Scandinavian school of thought relied on living conditions such as income and physical health that can be observed directly, while an American “quality of life” approach focused on “subjective wellbeing” (i.e., asking people about their happiness, agency, and satisfaction with life). Advocates of the latter argue that subjective wellbeing is the most direct measure of an individual’s lived experience. Defining wellbeing solely in subjective terms may not tell the whole story, however, since people’s expectations for their own wellbeing may be affected by their context and past experiences. For example, individuals in societies with relative deprivation may rate their subjective wellbeing higher because their basis for comparison is different than people in relatively well-off societies, or a drug addict might report being very happy in the moment despite not leading a healthy life overall. These days, there is widespread agreement that a mix of objective and subjective measures is likely to provide the best understanding of wellbeing.

THE CAPABILITY APPROACH AND THE RISE OF INDICATOR SYSTEMS

The insight that neither objective nor subjective measures fully describe wellbeing on their own raises an important question: how does one account for people’s differing abilities or desires to make use of the resources provided them? Beginning in the 1980s, economist Amartya Sen began addressing this dilemma in earnest. His capability approach, refined in subsequent decades with philosopher Martha Nussbaum, frames wellbeing through the lens of social justice, taking the unique circumstances and choices of individuals into account. Among other things, the capability approach notes that:

- Individuals draw varying levels of benefit from the same resources. As a result, assessing wellbeing is much more complex than considering whether and how resources are distributed. It’s one thing to say, for example, that food is available to a particular population; it’s quite another to consider whether that food can actually nourish and sustain a pregnant woman or someone who is allergic to some of its core ingredients. As a result, the capability approach pays more attention to specific states of being (e.g., being nourished) and activities (e.g., learning) than to external inputs.

- Having the freedom to make choices matters. Whether or not people take advantage of the opportunities they have, their ability to make decisions about how they pursue their lives is vital to wellbeing. The physical state of a person who is starving may be similar to that of someone who is fasting, but the right of the latter to choose his/her condition in an informed manner is crucial. Through this lens, all human beings must have the knowledge, skills, and opportunity to lead a meaningful life — beyond mere survival, a life “that they have reason to value.” Having the “capability” to achieve various states is therefore more significant than whether or not one actually achieves them.

Economists and international development scholars were quick to seize on Sen’s capability approach in their quest to break from an over-reliance on the GDP. As disillusioned as they were with standard macroeconomic measures, they knew that alternative metrics were needed in order for wellbeing to serve as a viable replacement. This gap led to a demand for new indicator systems that researchers and policymakers could use to translate quality of life into something that could be measured. Indicators, as they saw it, were necessary for wellbeing to move beyond a theoretical construct into something with practical significance. Beyond providing a means to count whether certain conditions are present, indicators could inform judgments about the success or failure of particular policy decisions, be used to hold people in power accountable to the impact of their work, and provide a common vocabulary by which nations, regions, or specific groups of people can track how they are faring.

In 1990, the United Nations Development Programme (UDNP), led by Pakistani scholar Mahbub ul Haq, began producing Human Development Reports meant to “shift the focus of development economics from national income accounting to people-centered policies.” In the process, they worked on a numerical index that could capture non-economic elements of wellbeing. Amartya Sen was involved; while he initially fretted that the capability approach was too complex to be boiled down to numbers, Haq and others eventually convinced him that policymakers would only take the capability approach seriously if a single index number was provided. Thus, the Human Development Index (HDI) was born.

The HDI is relatively simple. Its three dimensions are “a long and healthy life,” “being knowledgeable,” and a “decent standard of living.” The indicators are life expectancy at birth, mean years of schooling for adults over 25 and expected years of schooling for young children (calculated via a mix of UNESCO statistics and actual enrollment figures), and gross national income per capita. The geometric mean of numerical scores from these four indicators comprise the final HDI index score for any particular country.

The United States fares quite well under this system, ranking fifth out of 187 nations in 2012-13. UNDP’s Inequality-Adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI), however, tells a different story. It adjusts the HDI score based on the extent to which resources are more available to certain segments of the population than to others. (It uses a long list of surveys, including a few distributed by the World Bank and European Union, to do this.) A country with perfect equality would have identical HDI and IHDI scores. Across all countries in the survey, however, scores are adjusted by an average of 22%. Under IHDI, the United States’s ranking falls by more than twenty, while the remaining countries in the top five either hold their spots or shift by one or two.

The Human Development Index is just one example of a number of impressive, large-scale wellbeing indicator systems that have been developed in recent years. Below are a few of the more interesting and/or well-known efforts:

Gallup-Healthways Wellbeing Index

Claiming to be the “most proven, mature, and comprehensive measure of well-being in the world,” the Gallup-Healthways Wellbeing Index was unveiled in 2008 as a high-profile partnership between an international health care provider and arguably the best-known public opinion polling firm in the United States. Dubbed the “Dow Jones of health,” the index has a national and international version. The former measures life evaluation, physical health, emotional health, healthy behavior, work environment, and basic access via a 55-question survey distributed to 1,000 Americans per day. Its ultimate ambitions are to be “a daily measure determining the correlation between the places where people work and the communities in which they live, and how that and other factors impact their well-being.” The international edition is more modest, measuring five factors (purpose, social, financial, community, and physical) via ten specific questions included in Gallup’s World Poll, a monster survey that claims to represent 95% of the global population. Its reliance on self-reported perceptions of wellbeing sets it apart from other wellbeing indicators, and the impact of this difference in approach is notable: top Gallup-Healthways performers include a number of Latin American nations and territories such as Panama, Costa Rica, Puerto Rico, Belize, Chile, and Guatemala that don’t tend to rank highly in the other indices.

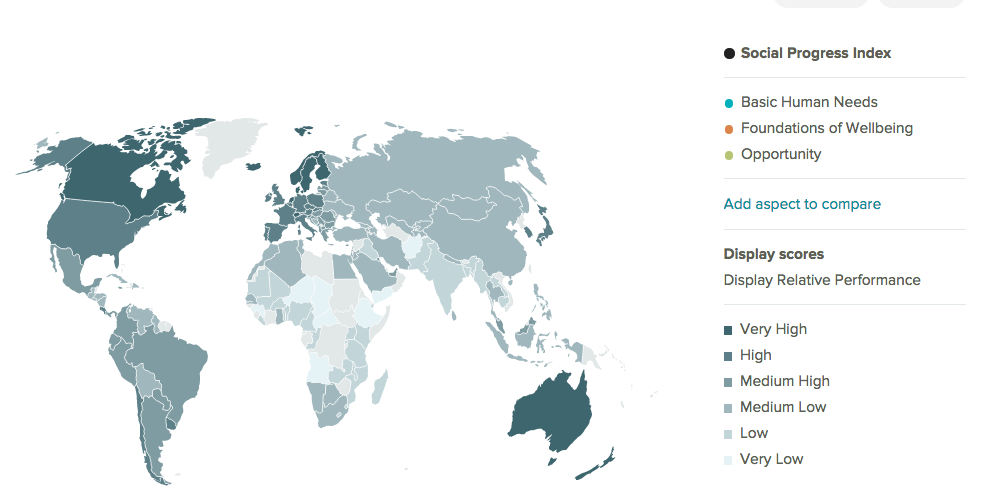

Social Progress Index

The Social Progress Imperative

Billed as a “holistic, 21st century assessment of the health of society,” the Social Progress Imperative was launched six years ago by the World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council on Philanthropy and Social Investing with the goal of “spur[ring] competition between nations to improve the environment for social innovation in the way the [Global Competitiveness Index] has done for enablers of economic growth.” With seed funding from Fundación Avina and the Skoll Foundation, it launched its first research project, the Social Progress Index (SPI), in 2013. The SPI examines a whopping 54 environmental and and social indicators that fall under three broad dimensions: “basic human needs,” “foundations of wellbeing,” and “opportunity.” Unlike the HDI, the index does not take economic indicators like income into account, and also privileges outcomes (like the number of people who have access to clean water) over inputs (like policies aimed at increasing that access). Each dimension has four components that all have equal weight in determining the country’s overall score. Components include nutrition and medical care, access to knowledge, information, communications, and personal rights and freedoms. The Social Progress Imperative’s website breaks down each score with colors that indicate areas of relative strength and weakness when compared with other nations with similar GDP.

OECD Better Life Index

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

In contrast to the previous examples with their fixed metric definitions and weights, OECD’s Better Life Index allows website visitors to manipulate the data on the agency’s 34 member nations according to their own personal definition of wellbeing. The Better Life index was launched in 2011 to put decisions about the most important aspects of wellbeing into the hands of the public. It’s not an entire free-for-all; the Better Life Index has eleven discrete topics taken from OECD’s other work on wellbeing indicators, split between material living conditions (including housing, income, and jobs), and the more nebulous quality of life (which in this case includes measures of community, education, environment, governance, health, life satisfaction, safety and work/life balance). Each topic is measured in turn by anywhere from one to four indicators, which run the gamut of statistics from the chance of workers losing their jobs in the last year to self-reported life satisfaction. Wellbeing scores can be broken out by gender, and each user can save his/her personal index and compare it with those of others.

Other examples of wellbeing and quality of life indicator systems include the Mercer Quality of Living Survey and two products from the Economist Intelligence Unit: the Global Liveability Survey and the Where-to-be-Born Index. The last of these, which is based on life satisfaction, is notable for its use of regression analysis to determine the relative weights of the 11 factors that make up the index, in contrast to the equal or user-determined weighting seen elsewhere. The Mercer and Global Liveability surveys rank quality of life in individual cities rather than entire nations; Vienna and Melbourne, respectively, take the top spots.

DESPERATELY SEEKING CULTURE?

These and other wellbeing indicator systems typically break down the general concepts of wellbeing or quality of life into a number of discrete domains like economic prosperity, education, or health. The domains are most often developed by experts working from theoretical conceptions of wellbeing, though a few cases draw heavily from definitions generated by the population being studied. There are a number of variations in the details, but a review of more than 20 indicator systems by a group of researchers led by Michael R. Hagerty identified seven domains that are common across nearly all instances:

- relationships with family and friends

- emotional wellbeing

- material wellbeing

- health

- work and productive activity

- feeling a part of one’s local community

- personal safety

You’ll note the absence of arts and culture from this list. In part, that’s because different societies have dramatically different ideas about what those words mean, and internationally comparable data sources relevant to culture are all but nonexistent. Robert Prescott-Allen, who in 2001 published a book detailing his own indicator system with an emphasis on the environmental impact of countries, originally set out to include culture as a top-level domain. Ultimately, he abandoned the idea, finding he could not identify cultural indicators that were consistent across a majority of nations included in his project.

Prescott-Allen is not alone; most indicator systems and other initiatives rooted in wellbeing have historically overlooked the role of arts and culture, and continue to do so. A recent advocacy campaign to integrate an explicit goal of cultural sustainability into the next iteration of the UN’s Millennium Development Goals appears to have failed, despite support from UNESCO itself and significant investment on the part of that agency in an indicator system to track culture’s role in sustainable development. Despite not achieving its primary objective, the advocacy campaign has yielded a useful set of ways to think about culture’s indirect contribution to wellbeing through priorities such as poverty reduction, education, and good governance.

Even so, a handful of individual countries have developed indices of wellbeing that include culture as a top-level concern. The aforementioned Gross National Happiness index adopted by the government of Bhutan is one example. The “Cultural Diversity and Resilience” domain of the index includes measures such as fluency in one of the regional dialects of Bhutan, expertise in one of thirteen traditional Bhutanese crafts (e.g. weaving, embroidery, blacksmithing, bamboo works, paper making, etc.), and knowledge of DriglamNamzha (the “expected behaviour [of consuming, clothing, moving] especially in formal occasions and in formal spaces”). In North America, the Canadian Index of Wellbeing includes the broad category of culture and leisure, which includes measures of leisure time as well as participation in activities such as camping, sports, or performing arts.

Another notable exception comes from the capability approach, or at least one particular version of it. Although Amartya Sen refuses to endorse “one pre-determined canonical list of capabilities” for the capability approach, his partner in crime, the philosopher Martha Nussbaum, has had no such compunctions — and her definition includes multiple nods to arts and culture. [1]

In 2000, Nussbaum published a list of “central human capabilities” as follows:

- Life

- Bodily Health

- Bodily Integrity

- Senses, Imagination, and Thought

- Emotions

- Practical Reason

- Affiliation

- living with and towards others

- social bases of self-respect and non-humiliation

- Other Species

- Play

- Control Over One’s Environment

- Political

- Material

In her explanation of this list, Nussbaum draws the clearest ties to arts and culture through the two principles of “Senses, Imagination, and Thought” and “Play.” The former includes “being able to use imagination and thought in connection with experiencing and producing works and events of one’s own choice, religious, literary, musical, and so forth,” and the latter refers to “being able to laugh, to play, to enjoy recreational activities.”

PART OF Y/OUR WORLD

Examining the connection between wellbeing and the arts [2] promises to move Createquity’s work forward in two respects. First, it adds some clarity and definition to our rather vague notion of the “concrete and meaningful ways” in which the arts improve people’s lives. And second, it connects the ideas embedded in our healthy arts ecosystem definition to a rich and rapidly expanding body of literature, lending added legitimacy to our work and opening the door to a broader cross-sectoral dialogue. The former of these benefits comes into play whenever we find ourselves having to compare different problems, interventions, or opportunities within the arts ecosystem. Our previous framework of “improving lives in concrete and meaningful ways” was on the right track, but weak in that it left “improving” and “meaningful” undefined. While not completely solving that problem, jumping on the wellbeing bandwagon does allow us to hone in on a range of likely definitions for those terms. Put another way, this new lens clarifies that the conditions and outcomes generated by a healthy arts ecosystem must increase the net wellbeing of society in order to constitute meaningful improvement in people’s lives.

The second benefit is perhaps even more important than the first. Scholars, philanthropists, policymakers, and others have long struggled to articulate how arts and culture fit into a broader conception of public goods and charitable aims, with the result that social innovation initiatives frequently treat the arts by different standards or ignore them entirely. Newer philanthropic movements such as effective altruism have sometimes demonstrated outright hostility to the arts, associating them with headline-grabbing capital or endowment gifts to major universities and large museums. Naturally, that prompts angry and defensive responses from the arts world in turn. Crucially, this distrust and lack of understanding on both sides arises from the absence of a common language with which to judge the value and success of initiatives across sectors. If we can describe the benefits and costs of arts ecosystem outcomes using the language of wellbeing in a way that celebrates rather than subsumes the unique things that make the arts special, that would lay the groundwork for a dialogue about the role of arts and culture in human progress in which all sides have a genuine stake.

Overall, we find the capability approach to be the most effective bridge between our existing healthy ecosystem definition and the fast-growing scholarship on wellbeing. It is particularly worth noting that Martha Nussbaum’s take on the capability approach is the clearest example we’ve found of integrating what have been commonly understood as the “intrinsic” benefits of the arts, such as joy, captivation, etc., into a broader definition of wellbeing. [3] This approach allows us to think of the arts as influencing overall wellbeing both directly, through developing the capabilities of Play and Senses, Imagination, and Thought, and indirectly through, for example, their impact on the capability of Bodily Health. Such a framework improves on the traditional delineation of “intrinsic” and “instrumental” benefits of the arts by proposing a consistent way to value both.

The capability approach is particularly helpful for clarifying what we mean when when we say that human beings today and in the future have “opportunities” to engage in certain types of arts participation. (The same could be said for other efforts in the arts field to “improve access to” things like arts engagement or arts education.) Its emphasis on personal choice and freedoms rather than behaviors suggests that a narrow focus on things like participation rates in an arts class or attendance figures at a concert hall cannot tell us much about wellbeing. Choosing not to engage in a specific arts activity or a long-term aesthetic pursuit can be a well-informed decision that yields greater wellbeing than would otherwise be the case. Likewise, the capability approach reminds us that providing people with access to resources is not enough; they must have the necessary training, skills, and agency to make use of them. This latter insight is consistent with the position that proactive steps should be taken to provide basic arts education opportunities to all, even if not everyone will choose to engage with the arts throughout their whole lives. For all these reasons, although they have not been as widely adopted as the capability approach in general, Nussbaum’s central human capabilities arguably offer a more compelling theoretical rationale for arts and culture’s inclusion in wellbeing than simply slapping arts participation indicators on top of a wellbeing measurement index.

WHERE WE GO FROM HERE

It’s important to remember that as much progress as wellbeing has made since 1948, this is very much a field that is still finding its way. Even the effective altruist community, with its self-assured rhetoric of doing “the most good possible,” is home to raging debates about what exactly that means in practice. So it should come as no surprise that as promising as we feel this direction to be for the arts, we have some thorny questions of our own:

- How does one weigh the benefits of art that is offensive to some people, but empowering to others? This is particularly tricky in cases when art is in direct dialogue — or conflict — with ideologies or belief systems that contribute to individuals’ subjective wellbeing. This push-pull appears particular to the field of arts and culture; it’s difficult to imagine how the health, social integration, or financial stability of one person could detract from that of another (beyond instances in which there aren’t enough resources to go around). In contrast, it’s not hard to imagine a scenario in which a culturally important but challenging artistic work has a negative (if short-lived) impact on the subjective wellbeing of the majority of a population. Yet that work may ultimately have a positive impact on future generations, which leads us to a second question:

- How does one account for changes in the value of arts and cultural products and experiences over time? This dilemma can play out both at the individual level, where cultural experiences that are not immediately pleasurable could nevertheless prove meaningful to the recipient later on; and at a societal level, where future generations may enjoy, appreciate, and/or use today’s cultural products in a very different way than their ancestors do. The latter situation is particularly vexing because there’s no defined time horizon for our definition of a healthy arts ecosystem, and thus a huge range of possibilities for how many people might be affected positively or negatively in the future by events taking place and decisions made in the present. Fortunately, that particular puzzle is mirrored in domains outside of the arts, and techniques such as discount rates have been established to deal with the issue, imperfect though they may be.

- How should different elements of wellbeing be weighed against each other? In theory, the only way to answer our opening question of which problems and interventions should receive top priority is to have a clear sense of how the holistic notion of wellbeing relates to its component parts. Yet the actual wellbeing indicator systems that have been put into practice largely seem to avoid this challenge, either declining to offer an overall wellbeing score entirely or weighing each component of the index equally — which, as many have pointed out, comes with its own set of problems. More interesting and intellectually defensible ways of determining weights exist, including expert judgments, crowdsourcing the personal opinions of members of the population under study, and statistical methods such as principal component analysis, two-stage factor analysis, or conjoint analysis. We aren’t in a position at this point to recommend a specific weighting scheme, but it seems like an important area for someone to explore going forward.

For all our never-ending debates about how and whether to measure the impact of the arts, our field may be well poised to contribute to this complex but fascinating dialogue that spans so many disciplines and decades. After all, if anyone is accustomed to making value judgments within an environment that resists quantification, it’s us! Committing to that conversation could open new doors as we contribute to a broader, shared understanding of human progress without having to downplay some of the arts’ more unique, intrinsic contributions. Entering those doors, however, will require leaving the arts cheerleading that many of us are accustomed to at the coat check. It will require contemplating what it looks like to offer the freedom to participate in arts and culture while simultaneously honoring those who decline the invitation.