(For a briefer edition of this analysis, check out the abridged version.)

“This may sound messy,” Nina Simon, engineer turned experience designer, writes of participatory projects. “It may [also] sound tremendously exciting.”

Summary

Written in 2010 as a handbook for museum professionals who want to engage audiences in deeper forms of participation, The Participatory Museum presents Nina Simon’s social, web-inspired approach to exhibits and partnerships. At the time of writing, Simon was a highly sought-after experience designer whose philosophy was made popular through her blog, Museum 2.0. Part argument for participation and part toolbox, The Participatory Museum aims to inspire readers’ enthusiasm about participatory design and prepare them to launch their own successful projects.

The book itself is the product of a participatory project. Simon used an online wiki format to allow readers to submit relevant case studies and assist with writing and eventually editing. The online version of the book features linked footnotes for the examples used throughout the text.

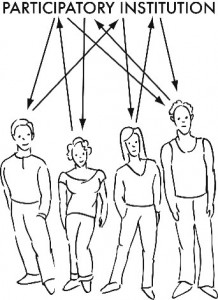

Taking cues from social websites like YouTube, Netflix, LibraryThing, and Flickr, The Participatory Museum explores how brick-and-mortar institutions can learn from virtual participatory experiences. Simon defines a participatory cultural institution as one in which “visitors can create, share, and connect with each other around content.” Participation encourages multidirectional content experiences: a museum, rather than limiting itself to sending information in the direction of visitors, can encourage those visitors to contribute information to the institution and even share among themselves. Participation also encourages more equitable relationships among all stakeholders, making objects and entire institutions more accessible.

All of this requires an adjustment in thinking about authority, the role of the visitor, and the flow of information between individual and institution. In participatory projects, museum staff members used to holding absolute authority in the interpretation of objects must cede some of that power to visitors. Simon asserts that the very process that makes participatory projects rewarding for museum audiences is often a source of apprehension for museum staff. Done right, according to Simon, “participatory projects create new value for the institution, participants, and non-participating audience members.”

Drawing by Jennifer Rae Atkins

Using the example of how interactivity has transformed entire organizations such as the Boston Children’s Museum, Simon imagines a future where some institutions are “wholly participatory.” The Participatory Museum advocates for the power of participatory design to fulfill idealistic mission statements about engagement, connection, and inspiring action. Nevertheless, Simon is careful to include the caveat that this new method of design isn’t meant to supplant traditional techniques but to augment them, and argues that the two can peacefully coexist.

Structure and scope

The book is organized into two sections. The first, more theoretical part lays out several participatory design principles, and the second details how four different models of participation can work in practice.

Participation in theory

For Simon, the first and perhaps most important point that undergirds all successful design is a clear connection between the institution’s mission and the benefits to be gained from a participatory project by the institution, participants, or audience. No one will be engaged – or fooled – if a museum halfheartedly invites participation because it has become trendy. To reap the rewards of participation, staff and leadership must understand how the project will advance the museum’s core purposes. This grounding in mission and clarity of benefits makes everything else possible.

The Participatory Museum identifies “two counter-intuitive design principles at the heart of successful participatory projects” that reappear throughout the book. The first is scaffolding, the guidance and constraints given to visitors to help frame the range and nature of responses generated. Scaffolding is necessary to set up a safe environment where audience members feel comfortable sharing and interacting with each other. Simon juxtaposes the completely open-ended request for participation with the thoughtfully narrow one.

Compare, for example, the open-ended dialogue program of British artist Jeremy Deller, It Is What It Is: Conversations About Iraq,with the Human Library, an event first held for youth at the Denmark Roskilde Festival in 2000. It Is What It Is attempted to encourage visitors to ask questions of people who had served in Iraq by creating a large gallery with provocative images from the country and installing living-room-style seating. At points throughout the exhibition, soldiers, translators, and others were on hand to answer questions from visitors. Simon argues that It Is What It Is lacked “sufficient scaffolding to robustly and consistently support dialogue”: the two times she saw it at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, there were just two guests sitting on couches next to a powerful object.

The Human Library explores similar terrain: it is intended for “anybody who is ready to talk with his or her own prejudice and stereotype and wants to spend an hour of time on this experience.” Participants select a “book” from a catalogue of stereotypes, such as a black Muslim, a cop, a Goth, or a quadriplegic; once at the “checkout counter,” they encounter a person embodying their chosen stereotype for a discussion lasting anywhere from 45 minutes to two hours. The experience was more carefully crafted, and it was a success at generating the kinds of provocative discussions the designers hoped for. The framing of the event as a library eased some of the expected reluctance in confronting visitors’ own prejudices, allowing participants to choose their own book provided a personal entry point into the activity, and even restricting the time helped set people’s expectations. Simon reasons that limitations make people more likely to participate and that better-defined parameters lead to higher-quality and more relevant participation.

Good scaffolding alone doesn’t automatically result in amazing social participation. Truly social interaction, Simon says, has to start with the individual, who begins to climb a participatory ladder from a personal entry point, her second design principle. “Me-to-We” design, a recasting of her own earlier hierarchy of social participation, guides visitors through those entry points to connections with content, and ultimately to other individuals.

Not everyone will always want to engage with others socially, even if an exhibit is designed to allow it. To categorize the different styles of participation, Simon looks to statistics on American adults from Forrester Research’s 2008 “social technographics” tool, which categorizes audience profiles in social media engagement.

Forrester Research’s social technographics participation ladder.

In this framework, audience profiles are based on types of activity. Creators make up a small part of the participation pie, whereas critics, collectors, joiners, spectators, and inactives represent the majority in social platforms – and all but the last two (not just creators) count as truly participatory. Good design acknowledges the mixed composition of audiences and provides an outlet for each role to be involved, enabling the actions of each audience type to enhance the experience of others.

Simon devotes considerable attention to two other elements of design: technologies for social experiences and social objects. Each of these concepts is meant to aid in moving toward the “we” end of design. Simon asserts that mediating technologies can make people “more comfortable socializing with strangers” within the physical space of the museum. For example, Internet Arm Wrestling, an exhibit set up concurrently in several science centers around the U.S., enabled long-distance personal interactions. Visitors at one institution sat behind a metal arm and a computer screen and arm wrestled someone elsewhere at the same center or hundreds of miles away at another. The exhibit succeeded in engaging audiences in types of behavior they would not normally try within a museum or, probably, anywhere.

Simon doesn’t neglect the role of objects themselves in prompting social interaction. Simon argues that “social objects,” a concept taken from engineer and sociologist Jyri Engestrom, perform a similar role as mediating technologies, allowing visitors to “focus their attention on a third thing rather than on each other, making interpersonal engagement more comfortable.” Social objects differ from regular ones in that they tend to spark interactions among audience members who see them. Simon uses the non-museum example of her dog, who serves as a focal point for social exchanges with passersby when she is out for a walk. Harnessing social potential is as much about good design choices as good object choices, and giving objects a social dimension is an art. It can involve making design tweaks, physically altering objects, or reworking interpretive tools such as panels and labels to make objects more personal, relational, active, and provocative..

Participation in practice

Shifting to the practical considerations for participation in the second part of the book, Simon borrows three categories of participation from the Public Participation in Scientific Research (PPSR) project of the Center for Advancement of Informal Science Education (CAISE) and supplies a fourth of her own. One chapter is dedicated to each of the participatory models:

- Contributory

- Collaborative

- Co-creative

- Hosted

Simon describes contributory projects as “casual flings between participants and institutions,” with the most common form being the comment box or feedback wall. As the name suggests, these projects solicit contributions from visitors, which can take the form of opinions, stories, or personal objects such as photographs. Of the four participatory models, contributory projects are the simplest to execute and can involve the most people. Even though these projects are relatively casual, scaffolding still helps institutions ask for and receive meaningful contributions through thoughtful questioning and modeling desired behavior. The London Science Museum incorporated visitor-donated toys into the exhibit Playing with Science, and visitors reported feeling a sense of ownership and pride in seeing their toys on display.

In collaborative projects, institutions still take the leading role in project development, but they work side by side with community members to create new exhibits, programs, and services. These projects usually require a higher level of commitment from participants than those in the contributory category. The National Building Museum in DC runs an annual program that collaborates with local youth to create an exhibit based on the photography and creative writing of community members. Participants take part in twelve classes and have the opportunity to “partially self-direct” an exhibit at the museum. To Simon, though, the exhibit is just the beginning. She asserts that the real measure of success for these projects is what happens after they end – specifically, whether participants remain involved with the institution beyond the project. Simon suggests establishing four non-overlapping roles for the management of collaborative projects: project director, community manager, instructors, and client representatives. Each of these roles balances different levels of authority and intimacy with participants, so keeping them distinct, Simon argues, is important to project success and staff sanity.

Co-creative projects may be undertaken at the initiative of outside participants. On the surface, these projects may look very similar to collaborative projects, but the key difference lies in the share of power between the institution and participants. Co-creative projects are demand-driven and “require institutional goals to take a backseat to community goals.” The special sauce that makes these projects successful is a mixture of non-specialists equipped to accomplish both community and institutional goals, and institutions genuinely desiring community input and leadership. Seattle’s Wing Luke Asian Museum uses the co-creative model exclusively in developing their exhibits. Wing Luke staff members facilitate the development of the themes, content, and form of the exhibits by a team of advisors from the community.

In hosted projects, outside participants have almost complete power. One of the most common of these is a late night social event or reception sponsored by an external organization, although some museums may turn over a set of rooms for exhibitions controlled entirely by someone else. In all of these projects, the outside partner carries out their own project within the museum’s space. Despite the near-total abdication of power in these projects, creative constraints are still useful in ensuring a degree of consistency between community-led projects and those led by professional staff.

While the participatory models range from less to more control on the part of the participants, Simon believes that they needn’t be attempted in any particular order and shouldn’t be seen as a progression. She has even demystified choosing among models through a chart that walks through assessing your commitment to community engagement, desired control over the project, preferred level of leadership, availability of staff, skills gained by participants and benefits to nonparticipants.

Toward the end of the book, Simon devotes chapters to evaluating and sustaining participation. Evaluating participatory projects can be especially tricky because it must focus not just on results for the multiple beneficiaries but also on the process itself. And even the best design can crumble with inadequate institutional support and management structures. Simon suggests a few methods to get staff comfortable with taking on more challenging participatory projects, such as encouraging them to “spend time on the front lines with visitors” or conduct audience research. She also offers several strategies for keeping momentum going with newly started participatory projects, including hiring a community manager and cultivating a participatory culture from the very top.

Analysis

After reading The Participatory Museum, museums and their staff, regardless of their size or resources or content, should be able to begin their journey to reinvigorating themselves, right? What’s good for the web must be good for the galleries? I have to admit that at first I had my doubts.

Specifically, I was skeptical that the book’s techniques would work in a museum like mine, the Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre in Laos: tiny, few staff, little money, no technology, almost no repeat visitors, and in a developing country. Forrester Research’s social technographics data draws on audiences in North America, Europe, Australia, Metro China, Japan and Korea – all relatively developed places. If any setting could test the limits of this model, it would be here. As I read, however, Simon seemed to anticipate my objections, and The Participatory Museum succeeded in allaying most of my questions about its applicability.

Many books meant as guides meander through abstractions and skimp on specifics, but The Participatory Museum is as dense in practical information as in theory. Tips (“Generally, a platform that has one-fourth to one-half of the space open provides a feeling of welcome and encourages visitors to share”) are peppered throughout the book. Simon reinforces her points with numerous case studies that illustrate both successful and unsuccessful attempts at encouraging participation. For example, in the section on collaboration, she shares her involvement with The Tech Virtual Test Zone, a 2007 project of the San Jose Tech Museum that did not turn out as expected. Simon’s own personal example of participatory failure was a poignant reminder that even seasoned designers don’t get things right all the time.

The examples are also diverse, featuring organizations from several countries, of many kinds and sizes, and at different points on the participation spectrum—some, even, from organizations similar to mine. To cite just a few cases, Simon presents an advice booth set up in the University of Washington-Seattle Student Center, a community photo-documentation project at the Vietnam Museum of Ethnology (VME), and a participatory book-tagging experiment in the Netherlands.

I also saw the applicability of Simon’s approach to the developing world firsthand recently, when my museum undertook a community-based participatory project similar to the VME’s. This work brought a flood of enthusiasm among community members previously untapped through traditional design methods. And a colleague in Indonesia recently quoted the book in justifying decisions she made within her museum. Between the examples in the text, and anecdotal evidence from colleagues, it’s clear that participation, as a tool, is useful in building engagement across a wide spectrum of audiences.

But can we trust the theories underlying The Participatory Museum’s recommendations for practice? While an exhaustive review of primary sources upon which the book draws is outside of the scope of this article, Simon certainly seems to have done her homework: her central typology of participatory projects (contributory, collaborative, co-creative, and hosted) is taken from the literature on public participation in scientific research. She deftly adapts it to the somewhat different context of museums, and added the final category (hosted) herself to account for the use of a museum’s space by an outside organization, where she argues persuasively that the principles of successful participation still apply.

That said, readers should be aware that most of the theory underlying The Participatory Museum had not been formally tested in a museum environment at the time the book was published. Simon speaks forcefully about the need for more and better evaluation of participatory projects; she calls the lack of it “probably the greatest contributing factor to their slow acceptance and use in the museum field.” The Participatory Museum seemingly does a good job of enlisting what assessment does exist and translating it into practical advice, and even lays out a blueprint for what good evaluation could look like, but the evidence presented in most cases is anecdotal. (There are exceptions, such as a 2002 impact study of Glasgow’s Open Museum, which lent objects to visitors in the community.) Purely on the basis of what was known in 2010, it is hard to be sure what tradeoffs would be involved in manifesting Simon’s ultimate vision of a new, wholly participatory kind of museum, or exactly how best to do it. Even so, The Participatory Museum gives every indication of being directionally correct, and an excellent guide to starting that process at an institution.

Implications

Whether you love or hate it, the impact of Simon’s book on the museum field is undeniable. With over 250 citations in books and journal articles, and required reading status in graduate museum studies programs, The Participatory Museum is widely touted as a must-read for museum professionals. The book has inspired conferences, institution-wide discussion sessions, and professional workshops around the country, and reignited debate over how to breathe life into decaying institutions. Simon continues to experiment with these principles at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History, where she has been executive director since 2011.

It’s hard to know how much credit The Participatory Museum can claim for this, but there has been a shift—or at least public perception of a shift— toward more participation in the four years since its publication. The Economist recently noted that museums were almost completely unrecognizable, having changed from being places “where people look on in awe” to being places “where they learn and argue.”

But is participation for everyone? There is a tension in The Participatory Museum between Simon’s utopian vision of wholly participatory institutions and her call for balance between traditional and participatory design. Writing about her divergent experiences during a visit to Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks in Wyoming in 2008, she admitted:

I am an elitist when it comes to national parks. I like my parks hard to access, sparsely populated, and minimal in services…I believe in lowering barriers to access and creating opportunities for visitors to use museums in diverse ways. On this trip, for the first time, I truly understood the position of people who disagree with me, those who feel that eating and boisterous talking in museums is not only undesirable but violating and painful.

If participatory design is not the only worthwhile kind of design, where is the proper balance? How do institutions and staff know when they’ve hit the participatory sweet spot and when they’ve gone too far?

Indeed, the principles Simon advocates in her book have met with resistance from some quarters. While many institutions have begun transforming themselves into the new kind of museum that Simon envisions, others hold to their support of quiet contemplation and traditional design and seem to believe that they can meet their missions effectively and satisfy their audiences without these design techniques. Bruce Bratton, a Santa Cruz resident, and Judith Dobrzynski, a New York Times writer, are the most recent standard-bearers of the camp that is critical not so much of The Participatory Museum as of the concept of participatory design itself. Dobrzynski believes that the participatory trend, or as she calls it, “the quest for experience,” has led to a field-wide identity crisis in which entertainment has taken over the previously quiet and contemplative environment for which museums were known. Bratton’s more personal attack took aim at Simon’s own museum, calling it a “hobby circus” and claiming that the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History had devolved into a community center under her leadership.

The Participatory Museum does acknowledge these concerns about audience members who don’t want to take part themselves or feel that others’ participatory experiences are intrusive. Early on in the book, Simon argues that the segment of the audience seeking a more traditional experience should not be left out of the process of “mapping out audiences of interest and brainstorming the experiences, information, and strategies that will resonate most with them” that is foundational to audience-centric design. The research profiling participant types notes that “passive” participants outnumber creators anyway, and through strategic design they can still benefit from others’ contributions. But at the end of the day, are audiences more engaged and are institutions meeting their missions more effectively through participatory design techniques?

For all the accolades and buzz it’s received, The Participatory Museum’s usefulness ultimately rests on the answers to those questions. We will need closer study of participatory work to fully understand the implications of the broader trends the book catalogues and appears to be ushering forward. What do we gain from participatory exhibits or institutional cultures of participation? What do we lose? Are there gaps between perception and reality on this front? (For example, the book presents little evidence that participatory design can make museum audiences less white.) Finally, how can we most effectively take Simon’s advice to put the audience first in any design, given the varied desires and priorities of individual members of that audience? The good news is that the success of The Participatory Museum and the speed at which its recommendations have been adopted should provide a wealth of material for researchers to begin answering these questions with more specificity in the years ahead.

Further reading:

- Nina Simon’s blog, Museum 2.0

- Jessica Shoemaker, A review of The Participatory Museum

- Sarah Jesse, What Would the Internet Do?

- University of Chicago Cultural Policy Center, Participatory Museum workshop

- Collections Link, Participation Portal

- Archaeology, Museums, & Outreach; Moving from Me to We

- Mike Murawski, Developing Questions for Visitor Participation

- Interviews with Nina Simon about the book:

- Huffington Post, Nina Simon and the Participatory Museum Model

- National Alliance for Media Arts and Culture, Five Question Q&A

- Smithsonian Magazine, Nina Simon, Museum Visionary

- Information and Design, The Participatory Museum