For all of the predictions flying back and forth about what 2013 holds for the arts and culture sector in the United States, one of the few things we can say with near-certainty is that 2013 will be a year of major transition for the Cultural Data Project (CDP). Our sector’s largest-scale effort to quantify and streamline the “value” of arts and culture across different regions, the CDP is breaking off from its original home at the Pew Charitable Trusts to become a separate nonprofit. Until now, the CDP has been governed by a local Pennsylvania-based board, but it recently launched a national board and announced Beth Tuttle as their new CEO, who will lead a strategic planning process to further evolve its scope and impact. These shifts, according to the CDP, will “put [it] in an even stronger position to serve the arts and culture community” and its “increasingly large and diverse number of constituents.”

As arts organizations are increasingly pressed to demonstrate tangible benefits, this turning point in the CDP’s history provides an opportunity to look back on its trajectory and examine ways to measure the contributions of arts and culture to society.

For those unfamiliar with the CDP and how it came to be, here is a little refresher:

Background of the CDP

The CDP launched in Pennsylvania in 2004 thanks to the collaboration between the Pew Charitable Trusts and a number of local funders. Using the CDP platform, arts and cultural organizations create an annual Data Profile based on their financial audit and quantitative programmatic data, such as the number of exhibitions or workshops held. It is an online tool that aims to help arts and cultural organizations “improve their financial management and services to communities” by streamlining, storing and aggregating data on their financial and programmatic activities each year.

In grantseeking, it functions a little bit like the Common Application for undergraduate college admissions, which some funders have emulated through standardized application templates; once organizations create Data Profiles they can then submit customized reports to multiple funders. Arts organizations also have access to a variety of tools that illustrate trends in their performance from year to year, and can compare their data against other organizations in the region or across all states participating in the CDP.

The tools include:

- A Program Revenue and Marketing Expense Report, which explores the relationship between marketing expenses and attendance figures

- A Personnel Report, which outlines costs associated with staffing, salaries and benefits

- A Contributed Revenue and Fundraising Expense Report, which examines how changes in fundraising expenses effect contributed revenue

- The Financial Health Analysis, developed in partnership with the Nonprofit Finance Fund, which serves as a fiscal health “check up” and provides an overview of financial strengths, weaknesses and business dynamics

Users can tailor comparison reports according to detailed specifications. For example, if you’re a mid-sized theater company, you can see how your programming and marketing expenses compare to those of your peers. You can also see how they compare against, say, all arts organizations that were founded within a certain time frame and target a specific constituent group. CDP Help Desk Staff assists in running those reports, and with cleaning and checking the data that goes into creating a Data Profile, which consists of nearly 300 questions and requires 15 to 30 hours to complete.

Why go through such a complex process? For one thing, funders get a standardized profile with grant applications that allows them to easily compare organizations. Accordingly, most funders who support the CDP require that nonprofits submit their Data Profiles and a customized report with their grant applications. Furthermore, many funders are interested in research, and the CDP provides a massive data bank. The more funders require their constituents to use the CDP, the bigger the ultimate payoff for researchers: a regional (and, perhaps one day, national) aggregate of information about arts and cultural organizations, updated annually.

As for the cultural organizations that have to complete the Data Profile, those applying to multiple grantmakers requiring CDP reports receive the benefit of being able to submit detailed financial information in one format. If they participate over several years and take advantage of the reports to track and compare their progress, they also gain a better picture of their own strengths. The drawback comes for organizations with limited capacity to devote to completing the Data Profile, or for those seeking to evaluate more qualitative elements of their work. But therein lie the possibilities.

The CDP’s Impact to Date: The Research Perspective

Thirteen states currently take part in the CDP, with sixteen more expressing interest. (A list of participating states with links to their CDP Web sites is available here.) In the near-decade since the CDP launched, how has it benefited the myriad cultural organizations that input data and the researchers who analyze it?

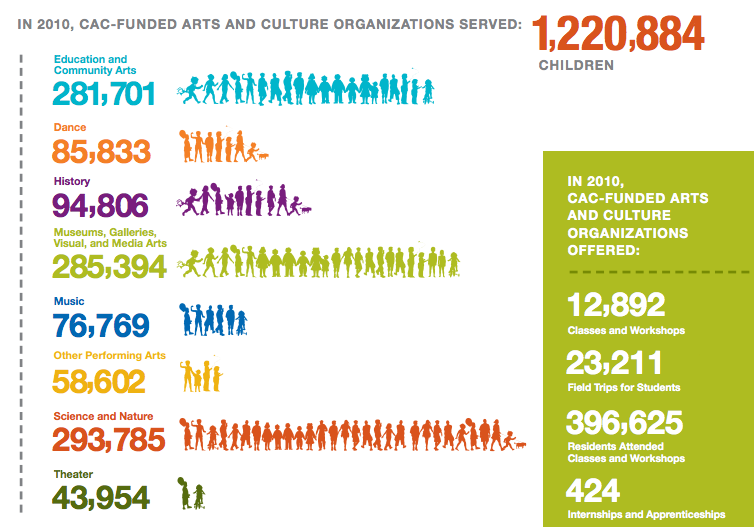

Most researchers to date have used CDP data to try to quantify the broad “impact” of the arts and culture sector in financial and programmatic terms, totaling up the number of people employed by arts and culture organizations in a given area, the number of public events, the number of attendees, etc. A snippet from Cuyahoga County’s Strengthening Communities 2011 report provides one such example:

The ability to quantify the scope and variety of the nonprofit arts and culture communities has proven invaluable to several advocacy campaigns. The Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance used CDP data to lead constituents across the state to successfully defeat a proposed tax on arts and culture activities. ArtServe Michigan’s Creative State Michigan Report, comprised mainly of CDP data, prompted the state’s Republican governor to propose a threefold increase in state arts funding.

Regardless of whether studies like these demonstrate that the arts generate economic growth, research resulting from the CDP has undoubtedly helped make the case for investment in the arts and culture and tell a more concrete story about people served. These efforts have been somewhat limited, however, by the “one size fits all” nature of the CDP’s construction. After all, attributes like financial health and the quantity of public events would be more accurately described as outputs rather than outcome or impact measures. The fact that CDP profiles are optional to fill out for organizations whose funders don’t require it also creates challenges for researchers who wish to generalize from CDP data to all nonprofit arts and culture organizations, since the CDP constitutes a nonrandom sample of such organizations. Recently, funders in California and New York have begun piloting small grant programs to support research projects using the CDP in their states; time will tell if these opportunities lead to a more diverse range of inquiries using the data.

The CDP’s Impact to Date: Arts Organizations’ Perspective

The CDP has been a boon to research and advocacy efforts, but cultural organizations themselves don’t always hear about that work, or take full advantage of the CDP’s resources. In 2012, the CDP conducted a survey of over 1,800 arts organizations charged with filling out a Data Profile every year. Arin Sullivan, the CDP’s Senior Associate for State-Based Activities, said that the survey found that 68 percent of respondents had never read a report that includes CDP data, like Cuyahoga County’s. This implies that researchers, and the CDP itself, need to close the feedback loop between research and the constituents being studied. In addition, according to Sullivan, the survey revealed that more than 40% of participating organizations have never run an annual, trend, or comparison report.

There are a number of possible reasons for this. Organizations simply may not be aware of the CDP reporting features. They may have limited staff capacity to run and analyze reports, particularly after devoting significant time to completing their Data Profile. Or they are aware of the reporting features, but don’t think they are worth using.

No matter what the reasons, these results suggest a range of perceptions about the CDP. To some organizations, it is simply a profile to complete in order to get a grant. To others, it is a resource that can help better inform their practice. The same survey that found nearly half of organizations don’t use CDP reporting tools also found that 45% of participants understood their own finances better as a result of completing the Profile. Of those respondents that did use CDP reports, 40% said it resulted in better transparency, 45% said they had a better sense of their progress and goals, and 56% said they had a better sense of their organization over time. These relatively low percentages suggest that even organizations taking full advantage of CDP reports do not always find them of substantial benefit.

Yet for some organizations, the CDP has been quite useful indeed. DanceWorks Chicago, for example, changed its entire accounting system to align with the format of the CDP. According to CEO Andreas Böttcher, many small organizations have little expertise in accounting, and until the advent of the CDP had no clear template to follow when setting up their books. Using the CDP was “onerous at first,” he said, “but once you have it, you can build a business plan based on what you have to report.”

DanceWorks has also made use of comparison reports. Böttcher said they’ve shown funders, for example, that not only is DanceWorks unique in its programming (which provides a laboratory for artistic growth to dancers, choreographers, and directors), but it is one of only a few organizations of its size to offer health insurance to dancers. Comparison reports also affirmed other things the company was doing well, despite its relative youth: its 80 individual donors reflect a larger funding pool than those of comparable, older organizations, and its web-based donations are 300% higher.

Other organizations have used the CDP to better track programmatic information, such as their most popular services or types of events. One such organization is the Rhode Island Historical Society, whose Executive Director, Morgan Grefe, used the CDP as an opportunity to make a greater commitment to program evaluation. According to Grefe, having to complete the Data Profile made program evaluation “the thing you can’t ignore instead of the thing you always put off.” She credits the CDP process with the Society’s increased attentiveness to more qualitative program data, which has had an effect on the organization’s work.

For example, staff members started tracking how many visitors to different historic sites used those sites as a “visitor’s center,” asking for brochures and other tourist information, but not participating in a tour of the building. Tracking such data enabled the Society to illustrate to public and private funders that the sites hold value to the tourist industry as well as to visitors concerned primarily with historic preservation. It also allows Grefe to make programmatic decisions, such as recruiting volunteers to fulfill visitor center functions or investing in more brochures.

An increasingly data-oriented attitude also led to the Society to launch the Rhode Island History Online Directory Initiative (RHODI). The RHODI Project will be “a comprehensive and detailed survey of Rhode Island’s history and heritage sector, [providing] not only trustworthy data on which to base future grant-funded proposals for such activities as collections cataloging, capacity building advice, preservation projects, educational programming, a virtual museum, but also the much needed impetus for synergies and collaborations.”

Beyond the Numbers: Looking Ahead as The CDP Expands

As these examples indicate, the CDP has shown potential in establishing and tracking organizational success measures that can encourage stronger business operations, advocate for the arts, and guide grantmaking. In order for that success to solidify, however, the CDP must gain buy-in from a broader group of stakeholders, and address the fact that its current ability to gauge the arts’ “impact” is limited.

Of course, the CDP can’t be expected to track and measure everything related to arts and culture. Perhaps in recognition of this fact, and in an effort to integrate CDP data with other available resources, Southern Methodist University recently announced a partnership with the CDP to launch the National Center for Arts Research (NCAR). Among other things, NCAR plans to launch an interactive “dashboard” where “arts leaders will be able to enter information about their organizations and see how they compare to the highest performance standards in areas such as community engagement, earned and contributed revenue and balance sheet health.” Assuming the effort manages to avoid redundancies with existing CDP infrastructure, it may fulfill its vision to become “a catalyst for the transformation and sustainability of the national arts and cultural community.”

At this point in the CDP’s history, it’s worth asking how it can further engage arts organizations, and what role it can play in evaluating more qualitative trends in cultural activities, such as audience loyalty and the evolution of programming. Since the organizations participating in the CDP range from zoos to art galleries, attempting to evaluate these aspects in any standardized way may be an exercise in insanity. What’s the dance education equivalent of a blockbuster museum exhibition? Nevertheless, there may be opportunities for the CDP to help organizations draw connections between CDP data and other reports, and to provide them with a broader toolkit of resources.

For example, for more than 20 years the League of American Orchestras has compiled a report of repertoire played by its member orchestras, including a list of the top 10 most frequently performed works, composers, and soloists. Though sadly only published in dense PDFs, one could track the repertoire of the top orchestras and determine if programming is, for example, becoming more conservative over time. Those same orchestras could make careful use of their own CDP data to make connections between programming choices and financial health.

The community and economic development sector, meanwhile, has attempted to build evaluative tools into a shared measurement system with a platform called Success Measures, which is smaller in scope but has certain similarities to the CDP. Success Measures provides its members, most of whom are organizations with little experience or capacity for program evaluation, with a set of evaluative tools (surveys, interview protocols, observational checklists, and so forth). They receive training on how to use the tools and then, using an online system similar to the CDP’s, upload, clean and analyze their data.

Participation in Success Measures is optional. By contrast, in each state where CDP operates, many funders require it as part of the application process, effectively enforcing participation. Given the CDP’s reach and the strong level of technical support it already provides, it is well poised to develop and disseminate additional tools. Suppose an organization was hoping to understand its audience retention rates, and had the option of accessing standardized survey tools as a CDP participant. The CDP would provide the organization with technical assistance in using the tools, in exchange for the survey results being added to the aggregate database. Such a system could not only strengthen the value of participating in the CDP, but also take a step toward a deeper understanding of “impact.” New tools — even optional ones — can motivate organizations to take a closer look at their activities, perhaps discovering how cultural choices affect their bottom line over time, or if their audience development efforts are truly paying off.

No matter how (and if) it chooses to expand, a few things about the CDP are clear:

- It has propelled an ongoing conversation about the economic role of arts and culture

- It may yet build the capacity of the field as a whole if it more directly engages the arts and culture organizations it aims to serve

- To do so, it needs to clarify and draw greater attention to the existing benefits of using the system, and stay alert to organizations’ needs moving forward

With both for-profit and nonprofit sectors gravitating toward Big Data (and seeking more and more people to help them make sense of that data), the CDP can take a lead in ensuring that aggregate information is not only useful to researchers studying the arts and culture sector, but also to the organizations — large and small, vibrant and struggling — that are its engine.

(Talia Gibas is Manager, Arts for All at the Los Angeles County Arts Commission and a past Createquity Writing Fellow. Amanda Keil is a mezzo-soprano and writer based in New York City.)