In Createquity’s vision of a healthy arts ecosystem, each human being today and in the future has an opportunity to participate in the arts at a level suited to that person’s interest and skill. Accordingly, it’s important for us to understand the ways in which the current arts ecosystem falls short of this ideal, in particular by failing to include everyone equally or give everyone a fair shot at the opportunities they deserve.

Why We Care

In the United States, a long history of cultural equity activism has drawn attention to ways in which the essential infrastructure of the arts sector – in particular, the nonprofit arts funding system – was originally shaped by and for wealthy, white patrons. The lingering effects of this history are evident today in the disproportionate incidence of organizations celebrating European art forms among the largest-budget institutions in most metropolitan areas.

Createquity’s informed hypothesis is that wealthy donors, who are disproportionately white, continue to influence the art that organizations produce/present, prompting those organizations to cater to donors’ personal preferences and tastes rather than those of the broader community. These patrons and civic leaders have also shaped (and in many cases continue to shape) the formative strategic directions of numerous public and private funders, resulting in ongoing disproportionate subsidies to large institutions founded by people of European descent. The cascading effects of this imbalance are many, potentially decreasing access to meaningful arts experiences and opportunities to make a living as an artist for people of color and other marginalized groups.

What We Know

In the United States, a wealth of data supports the notion that the nonprofit arts sector suffers from a lack of racial and other forms of diversity, particularly among larger-budget institutions working in European art forms. Approximately 84% of curatorial, educational, and leadership jobs at art museums are occupied by white people (compared to less than 63% of the population as a whole), while 92% of board members at orchestras are white. According to the Foundation Center’s 2015 Foundation Giving Forecast Survey, more than 92% of arts foundation presidents and 87% of arts foundation board members are white. This lack of diversity extends to top leadership in commercial arts industries as well, and acting, directing, and other opportunities in Hollywood disproportionately favor white men.

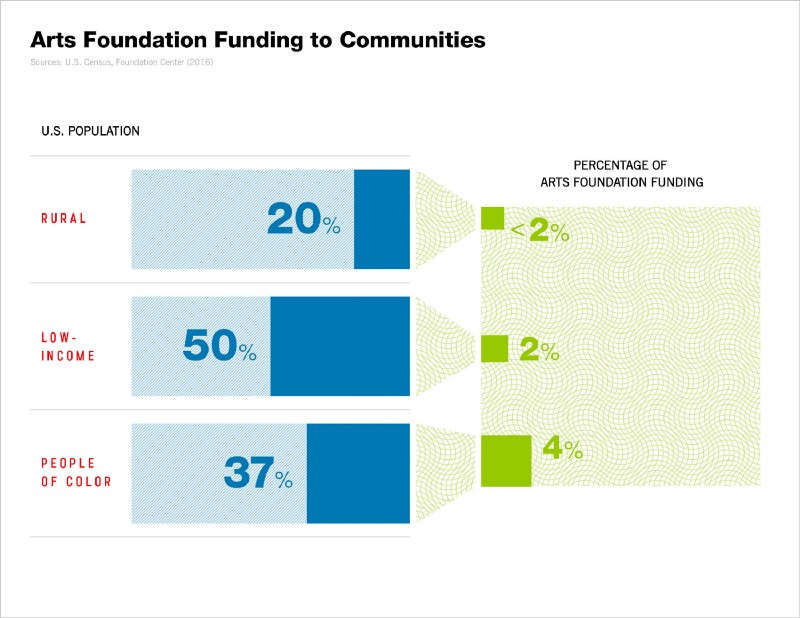

Meanwhile, giving to nonprofit arts organizations appears to be highly stratified, with just 2% of arts organizations in the United States receiving more than half of total contributed income. In addition, there are clear signs that current funding patterns disfavor people of color, rural communities, and low-income neighborhoods.

Knowledge of this nature can help establish the existence of a problem, but for our sector to move forward, we must have a clear and shared understanding of what cultural equity looks like in practice. And therein lies the rub: as we delved into the literature around the history of cultural equity activism and consulted experts in the space, it became evident that this shared understanding simply doesn’t exist.

There is an inherent difficulty in examining positions forged through dialogue via documents authored by a few, and any attempt to develop a taxonomy will have its flaws. But in our own conversations, we found it helpful to divide the visions for success we were reading and hearing from advocates into four archetypes: Diversity, Prosperity, Redistribution, and Self-Determination.

- Diversity: The Diversity vision for cultural equity argues that so-called “mainstream” institutions are far too homogeneous, and calls for them to become more reflective of the communities they serve in light of the country’s changing demographics. Historically, conversations about diversity have tended to focus first on audiences (reach), then on programming, and finally on leadership.

- Prosperity: The Prosperity vision takes Diversity’s belief in the power of organizational scale and applies it to institutions started and led by artists of color. These institutions follow the standard model of nonprofit growth, with an eye toward long-term sustainability. An underlying assumption of Prosperity is that large, established institutions of color will last longer than smaller, neighborhood-based organizations, and thus provide more benefit to society over many generations.

- Redistribution: Redistribution favors a larger pool of recipients for contributed income, particularly from grantmakers. Advocates of Redistribution argue that people of color, rural communities, LGBT communities, and others are socially and economically marginalized by our society and therefore have less access to wealth to support their work in the arts. An equitable distribution–a redistribution–of funds towards organizations originating in and serving marginalized communities is the best way to address this imbalance.

- Self-Determination: The Self-Determination theory of cultural equity is the most radical departure from the status quo. It calls for full participation in and expression of cultural life for marginalized communities through models that are organic to those communities, and that look beyond established nonprofit arts funding and advocacy tactics.

These four visions are not mutually exclusive, nor are their advocates. Yet in practice, the tensions between these ideas can be a source of great confusion if they are not called out explicitly. Some of these tensions include:

The Role of Race

Cultural equity is a conversation that is rooted in, but not exclusively about, race. Diversity often starts from a reference point of race, but advocates for Diversity frequently encounter pressure to use other measures of social difference such as age, class, and disability status. Prosperity tends to be squarely focused on artists of color, but the Redistribution and Self-Determination visions are more directly aligned with the social justice movement, and thus consider LGBT, rural and other frames alongside race (albeit from an intersectional perspective).

The Value (and Cost) of Integration

The Diversity vision is strongly centered on the idea of people coming together to understand and celebrate their differences. Yet for some activists, this expectation to share and share alike ignores oppressed groups’ right to meaningful control of resources, traditions, and spaces that they can call their own.

The Centrality of Institutions

Diversity and Prosperity see institutions as vital infrastructure with enormous potential for community benefit. Redistribution sees value in institutions too, but is also keenly aware of how institutional values (e.g., prioritizing financial growth, sustainability, and formal structures) have historically been biased against marginalized communities. Self-Determination thinks institutional values are a corrupting influence and rejects the idea of institutions being the only model of health, questioning even bedrock institutions like the nonprofit sector itself.

Cultural Norms

Implicitly, Diversity and Prosperity embrace several core elements of dominant American culture that Redistribution and Self-Determination tend to be wary of. One of the most important of these norms involves using an individual rather than group lens to talk about benefits and harm. Redistribution and Self-Determination also tend to place more of an emphasis on heritage and identity in defining culture as opposed to individual creativity and abstract expression, and see social consciousness as an important element of artistic work.

What about the Money?

The Redistribution vision sees access to financial capital as a crucial lever for justice, which implicitly buys into a capitalist framework. The Self-Determination vision, on the other hand, sees capitalism as a white supremacist institution and is more interested in creating spaces and contexts for marginalized communities to have full control over their circumstances, even if that means leaving money on the table.

What We Don’t Know

The existing research leaves several key questions unexplored, the answers to which would help the field direct future efforts to advance cultural equity more strategically.

- How does the level of exposure to and/or interest in arts careers and arts administration jobs differ across race and other demographics (e.g. income, education)?

- What are the ingredients of a cultural experience that people find valuable? Are those ingredients consistent across demographics? Are the demographics of the staff (artistic, programming, and administrative) and board at arts and cultural organizations predictive of a) the demographics of their participants and b) the quality of experience that participants have?

- What effect does the scale of an arts organization (or an organization with arts programming) have on its ability to create specific benefits for artists, audiences, and communities of color? How do networks of larger and smaller organizations perform relative to each other in facilitating these benefits? Does the influence of wealthy donors, funders, and customers tend to promote or harm an organization’s ability to deliver these benefits?

- Are arts activities designed to combat racism and other forms of oppression effective in that goal? How do they compare to other anti-oppression strategies, and do they make those strategies more effective when used in combination? What is the role of the arts in helping oppressed peoples cope, survive, and thrive?

What You Can Do With This Information

We hope this information can be helpful to organizations and agencies of all sizes seeking to define, measure, and achieve equity goals. Honest conversations about cultural equity are critical for all arts organizations, but particularly those that serve a leadership function in the sector – e.g., local arts councils, government agencies, foundations, etc. – who work with a cohort of organizations that may have varying ideas about what equity means in practice. We recommend discussing with your board/stakeholders and colleagues your collective vision of cultural equity going forward; which archetype best fits your goals, organizational structure, and institutional identity? Some other questions you might consider include:

- How important is racial justice to your institutional mission?

- For organizations working in European-descended art forms, how important is the preservation and advancement of that art form to your institutional mission? If the needs of the art form and the desires of your local community are in tension, what gets priority?

- At what point do most institutions tend to prioritize their own preservation over the health of the entire arts ecosystem?

- One of the most important American cultural norms involves using an individual rather than group lens to talk about benefits and harm. What are some other norms that often go unexamined? How do they impact the work of your institution?

- For funders specifically, if you want to support communities of color out of a desire for economic and/or racial justice, how can you ensure that you are transferring not just resources but meaningful control/ownership of those resources?

- Pursuing future inquiry through a wellbeing or quality-of-life lens may be an effective tactic for building bridges between visions and the ideologies they represent, by enabling the relative value of components of each vision to be understood as part of an integrated whole. How do we measure and evaluate wellbeing in the context of self-determination? Who decides what’s good for you?

Resource List

On the Cultural Specificity of Symphony Orchestras (2017)

What is the role of white-led arts institutions in a race-conscious world?

As longstanding concerns about cultural equity find voice in policy initiatives, leaders at arts organizations that celebrate European cultural heritage may have to ask whether their loyalty is more to their art form or their local community.

Making Sense of Cultural Equity (2016)

When visions of a better future diverge, how do we choose a path forward?

Cultural equity is increasingly a topic of concern for the arts ecosystem, but not everyone agrees on what it means in practice. This article examines four overlapping but distinct visions of success advanced by cultural equity advocates over the past half century, the assumptions underlying each of these visions, and the fault lines running between them.

Notes to “Making Sense of Cultural Equity” (2016)

Full bibliography and endnotes, along with a set of definitions related to common terms in the discussion of cultural equity.

Who Will Be the Next Arts Revolutionary? (2016)

The story of how the nonprofit arts sector got started offers would-be changemakers some clues.

This article looks into how the non-profit organization became the dominant model for the sector, reaching a boom during the mid-20th century.

Notes to “Who Will Be the Next Arts Revolutionary?” (2016)

Full bibliography and endnotes, especially point 5.

Who Can Afford to Be A Starving Artist? (2016)

The key to success may be risk tolerance, not talent.

This feature article examines whether there is evidence that risk dissuades individuals from economically disadvantaged backgrounds from pursuing arts careers.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Race (2013)

What can we do to create an open environment for talking honestly about race relations in all of their kaleidoscopic, maddening, shame-inducing complexity?

Fusing Arts, Culture, and Social Change (2013)

A report published by NCRP argues that arts philanthropy, as currently structured, perpetuates inequality across the arts and culture sector by disproportionately funding large institutions that focus on Western European traditions.

Createquity Podcasts

- “Createquity Podcast Series 4: Approaching Cultural Equity” (2016)

Different visions of cultural equity, and how pursuing those visions has played out in practice. - “Createquity Podcast Series 1: Watch Where You’re Giving” (2016)

Effective altruism and the arts.

Cover image: Negro Ensemble Company National Tour, 1968, by Philip Mallory Jones