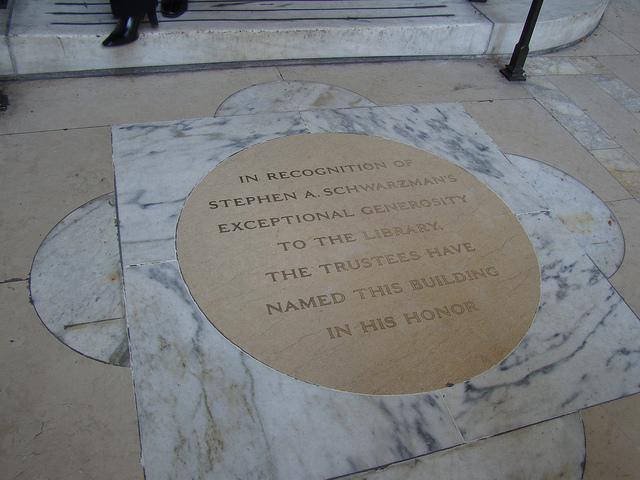

Plaque honoring financier Stephen Schwarzman, after whom the New York Public Library’s flagship building is named. Photo by Flickr user vagueonthehow.

Young whites poring over books, memorizin’ but never learning

And I wonder how the fuck they’ll justify genocide.

“I…I was in the library, honest to God, I didn’t even know.”

—From “The Library,” by Felipe Luciano of The Original Last Poets

On March 7 of this year, my friend and I attended a screening of the film Right On!, a seminal creation of the Harlem spoken word poetry movement of the 1960s. Featuring 28 performances by a group called The Original Last Poets, Right On! is essentially a double-album-length music video that presaged MTV by over a decade. The film’s monologues-with-a-beat offer a brutally honest window into black urban life and identity in the midst of the civil rights era. According to the movie’s producer, as relayed by the marketing copy accompanying the event, it was “the first ‘totally black film’ making ‘no concession in language and symbolism to white audiences.’” It was intense, confrontational, and not quite like anything I’d seen before. I loved it.

“The Library,” quoted above, is not even close to the angriest number in Right On!’s hit parade. But watching the images of what is now the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building at the New York Public Library pass by as Felipe Luciano’s fellow Last Poets mockingly intoned “The Liiiiii-bra-ree,” I couldn’t help but revel in the irony of my location: the Museum of Modern Art.

*

As it turns out, Right On!’s run at MoMA was the world premiere of a digitally restored version of the film. Lost to the public for many years, Right On! had been little more than a fading memory until the museum’s To Save and Project festival of film preservation undertook the challenge of bringing it back to life with support from donors Celeste Bartos and Paul Newman.

The work of restoring and presenting Right On! to the public is the sort of thing that institutions like MoMA routinely cite in grant applications as proof of their commitment to diversity. Yet MoMA could hardly have been a more iconic symbol of the white establishment to serve as a setting for the Poets’ time-lapsed performance. Forged from Rockefeller privilege, MoMA was founded to promote the artistry of European modernism, and the most famous works in its collection are nearly all by dead white men. It has $1 billion in net assets, pays its (white) director a seven-figure salary that places him among the best-paid nonprofit executives in New York, and charges among the highest admission fees in the country for an art museum. It was the first target of Occupy Museums. The very room where the Right On! screening took place, The Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1, first gained notoriety within the filmmaking community for its D. W. Griffith retrospective in 1940, which surely must have included the racist and Ku-Klux-Klan-reviving Birth of A Nation.

Remarkably, the Poets themselves made an appearance at the opening night of the run. I can only guess that it was a heart-warming spectacle of racial healing and harmony, as Luciano didn’t respond to my request to interview him. All I know is that the following night, the night I was there, I counted two black people in the audience.

*

Earlier this year, Talia Gibas analyzed Holly Sidford’s manifesto “Fusing Arts, Culture, and Social Change” for Createquity. “Fusing” has become a rallying cry for cultural equity advocates who believe that philanthropic resources are unjustly concentrated in venerable institutions with white European roots like MoMA. The study analyzed the flow of philanthropic dollars to the arts using data from the Foundation Center, and found that less than 10% of arts grant dollars went to serve marginalized communities, including African Americans.

Interestingly, the restoration of Right On!, undertaken by MoMA with the support of individual donors, not foundations, would not have registered as a project serving a marginalized community under Sidford’s methodology. And by excavating a treasure of the black cultural canon from functional oblivion with (from all appearances) the full cooperation of the creative individuals involved, one could argue that MoMA is doing the African American community a wonderful service, fulfilling its role as custodian of heritage in a truly inclusive way. But it’s also not hard to see the transfer in setting from underground movie theater in heady 1970 to establishment art museum in 2013 as a particularly insidious kind of cultural appropriation. It was a striking experience to watch Right On! from the comfort of MoMA, of all places. It was, in fact, like being in a museum, as if there were a glass wall between the movie and me allowing me to appreciate it as a cultural object while preventing me from truly entering its world. The raw, unfiltered power and emotion directed at the camera was boxed in and partially neutered by the time it reached me on the other side of the screen, sitting next to my white college friend and the many white people in the room who could have been my friends if I’d happened to come across them in a different context. As unmistakable as the film’s point of view was, it was easy, too easy, to compartmentalize it as an artifact of a different era, a time when revolution was in the air and the evils of racism were upfront and obvious.

*

I’m not sure there is anything that has claimed as high a brain-energy-expended-to-public-output-generated ratio for me as race this past year. Way back in February, some of you might recall, I inserted myself into a discussion about race and the arts that had been started by New Beans’s Clayton Lord, then Director of Audience Development for Theatre Bay Area and now VP of Local Arts Advancement for Americans for the Arts. At the time, I noted that “virtually all of the recent discussion…in this particular corner of the blogosphere [was] happening among well-meaning white liberals who just can’t help themselves from occupying public space with their opinions.” I wasn’t the only one who noticed. Roberto Bedoya, head of the Tucson Pima Arts Council in Arizona and a longtime follower of this blog, thanked me for pointing it out and challenged me and five other bloggers—pale pasties, all of us—to “share with us some of [our] good thinking and deep reflection on [our] understanding of how the White Racial Frame intersects with cultural polices and cultural practices.” Piece of cake, right?

You can read the responses from Clay, Doug, Nina, Barry, Diane, and Roberto himself at the links provided. As eager as I was to participate (I promised I would, after all), extracting words from my brain these past months was like squeezing blood from a stone. The topic of race offers a white liberal like me a frustratingly narrow range of socially acceptable rhetoric. Like any self-respecting contrarian, I have no interest in saying what’s already been said, but at the same time I felt woefully underprepared to confidently take the conversation in a new direction. It took a long time, a lot of background research, and many discussions with family, friends and social and professional acquaintances who consciously engage with issues around race before I finally felt comfortable airing my views in public.

If there’s one positive and concrete suggestion I can offer in the wake of that learning process, it’s that we do what we can to create an open environment for talking honestly about race relations in all of their kaleidoscopic, maddening, shame-inducing complexity. The dialogue that Clay and Roberto have started is a great first step in that direction, but we need to keep it going if we truly want to achieve more than symbolic progress towards a more racially just sector. And the more I learn, the more strongly I suspect that in order to keep that dialogue going in an authentic way, we are going to need to take it into some very uncomfortable, challenging territory – for white people and non-white people alike, for anti-racism advocates and white privilege apologists both.

*

Several of my fellow bloggers who responded to Roberto’s prompt made valuable points about the need and opportunity to be more inclusive and welcoming in our institutions’ programming and audience engagement practices. And certain artistic works undoubtedly have the power to hold a mirror up to ourselves and question the assumptions of our environment, as Right On! was able to do for me. But I feel that this conversation is missing something crucial if we neglect to expand the frame outward, to grapple with how our country and society’s dysfunctional relationship with race informs and warps our lives more generally.

Art and arts organizations are not capable of solving racism on their own. It’s not that the arts have nothing to say about race or that diverse cultural expressions aren’t important, but in the absence of a clear and shared understanding of the underlying factors that perpetuate racism, I fear that arts-centric interventions can all too often end up being little more than a band-aid – a way to reassure ourselves that we’re doing something important and valuable when in reality we’re really having very little impact at all. I believe that the sooner we as a field start framing our efforts not around “what can we do as artists and arts administrators to promote diversity?” but rather “how does racial injustice manifest today, what are its root causes, and how can we as human beings most effectively be part of the solution?”, the sooner we’ll actually have something to be proud of.

For example, I’ve now been a part of several organizations that have struggled with the fact that their staffs are mostly white. One of the most visible commitments to diversity that an organization can make is to have strong representation of people of color among its staff, board, and leadership. Not surprisingly, then, managers typically have these considerations at back of mind when entering the hiring process, and sometimes even explicitly consider race as a factor in their decision. And yet they get frustrated when they are unable to find competitive candidates of color at a rate that would, as advocated by Robert Bush, make them “look like the people [they] serve.”

Simple statistics, however, quickly start to illuminate some of the reasons behind this frustration. Virtually every arts administration job I’ve ever seen requires a Bachelor’s degree as a minimum condition of employment. I’m willing to bet that most arts administrators don’t realize that fewer than a third of American adults over the age of 25 have one. More to the point, however, black and Hispanic adults are 40 to 60 percent less likely respectively to have graduated from college than whites. So if having a Bachelor’s truly is a requirement for doing the job well*, then “success” as it relates to representativeness actually means matching the proportion of people with college degrees, not the general population.

Of course, if you have any conscience at all, the above rationalization is unsatisfying. It openly admits and does absolutely nothing about a basic racial equity issue: access to opportunities based on educational attainment. But therein lies the rub: if we actually care that the disparity in college graduation rates is causing our application pool to be less diverse, that is if we care enough to do something about it, our daily work may not be the most appropriate forum in which to take action. What’s needed to close that gap, in all likelihood, goes way beyond the arts.

(*This is, of course, an important question to examine in its own right, but in the interests of not biting off more than I can chew with one article, I’m going to sidestep it for now.)

*

The stark disparity in college graduation rates described above can be seen as one manifestation of the so-called “achievement gap” between white students and black and Hispanic students. This achievement gap is present from a very early age, though not necessarily birth. One contributing factor to the achievement gap, though undoubtedly not the whole story, is the vast differential in the quality of the schools available to white students vs. students of color, especially in urban environments.

America’s cities are highly segregated geographically, in part a vestige of real estate redlining practices and white flight following the Second Great Migration in the mid-20th century. Even today, there is evidence that white homebuyers are willing to pay more money not to have to live in a neighborhood with lots of people of color. As a result, by some measures school systems in the United States are even more segregated today than they were when Brown vs. Board of Education was first implemented in the 1960s. Meanwhile, school systems are governed by local rules and jurisdictions and, crucially, paid for via local property taxes. Ever wonder why people move to the suburbs to send their kids to good schools? Well, that’s why. On a per-capita basis, suburbs are much wealthier than urban cores and therefore can afford schools that are less crowded and feature more amenities for their students. People who don’t follow the education field may not realize that public school systems are struggling in large cities all across the country, not just where they live.

There is no magic bullet for fighting racial inequity; in the Atlantic Cities recently, for example, Emily Badger makes the case that establishing universal preschool is the best single thing we could do, but even the rosiest projections offered in that article make clear that such a measure would hardly erase the achievement gap. Nevertheless, as educated professionals, one action we could take that might actually make a difference is to locate ourselves in areas where our tax dollars will go to support these struggling school systems. And yet, many of my white peers are doing the exact opposite: explicitly shopping for real estate by school district, trying their best to ensure that their kid(s) will be less likely to end up in a bad situation – and, incidentally, a lot less likely to be surrounded by kids of color.

It’s awfully tough to ask someone to choose between fighting for racial equity and forgoing the best possible education for their child. I believe that sacrifice is a virtue, but I am not enough of a romantic to count on it as a large-scale strategy for social change. Perhaps the real enemy here, then, is not the racism-perpetuating behavior, but the system that sets up the incentives that encourage it. In this case, that system is the funding of public school systems based on local property taxes. If we really want to attack this part of the problem at its core, perhaps we should be advocating instead for a system that runs schools locally but funds them nationally, presumably through an expanded Department of Education. What can arts organizations do to push forward that outcome? And why is hardly anyone else talking about it?

Let’s take a step back for a minute and remember how we got here. We were wondering how a hiring manager could get her staff to better reflect the diversity of her community. Now, 900-some-odd words later, we’re talking about advocating for a giant expansion of the Department of Education, universal preschool, and in the meantime intentionally sending our kids to substandard schools. Does it make sense now why, despite all of our conversations about race and privilege, nothing ever seems to change?

*

I like to think of myself as a technocrat – as I get older, I find myself becoming less and less interested in what sounds good and more and more interested in what works. On this blog and at my day job alike, I advocate for “evidence-based decision-making.” I champion logic models and theories of change as tools for taking apart complex systems. I push for a big-picture, strategic approach to everything, most of all to gigantic social clusterfucks that take lifetimes to unravel.

I don’t do these things for giggles or to increase my SEO ranking. I do them because I genuinely believe in the power of analytical thinking to help us make sense of the world. Using good research methodologies can tell us useful things like the fact that even your mom smoking crack while she’s pregnant with you doesn’t screw up your life anywhere near as much as being born into poverty, or that educating parents on how to parent better might just be a way to fix some of these problems.

In order to really be able to use research, you have to keep an open mind. You’re not going to learn anything if you’re not willing to let the research surprise you. And sometimes those surprises can be an unpleasant source of cognitive dissonance.

I think this is where I have the greatest difficulty with the “discourse” around race as I’ve most often experienced it in this country. Some months ago I wrote on this blog about the phenomenon of “mood affiliation,” a term coined by economist Tyler Cowen to refer (as I interpret it) to a tendency among participants in debates to ally themselves with a certain “side” and subordinate new facts or information to the preferred interpretation of their “team.” A more widely recognized name for this sort of thing is confirmation bias.

I feel like there’s a whole lot of mood affiliation that goes on in conversations about race. The population subgroups that are active in these conversations place a high value on coordinated action and messaging. That means that, if you consider yourself an anti-racist and would like for others to perceive you that way as well, there are very real social and even professional risks associated with taking certain positions on issues that may not be clear-cut at all. Something like stop-and-frisk may not be good policy (it’s not), but we need to be able to ask the question of whether it actually works before dismissing it on moral grounds – and, more importantly, be prepared to answer the question of what if it does? Alas, stories about race become politicized so quickly that it becomes much more difficult to take an unbiased, critical look at the situation than it is to rely on whatever position one’s identity group has rallied behind.

For that reason, what I crave the most is to see conversations about race imbued with the complexity and nuance they deserve. I’m not talking about the throw-up-our-hands-and-declare-defeat kind of acknowledgement of complexity, but the okay-let’s-get-into-the-weeds-and-figure-this-shit-out kind. In order for that to happen, critiques that question conventional wisdom about race are going to have to play a bigger role. Critiques like these:

- How important is race relative to other forms of difference? Race gets a lot of attention, but is it the most relevant lens through which to view social justice in the present-day United States? I’ve noticed that the idea of comparing injustices to each other gets a lot of pushback from anti-racists; the phrase “oppression Olympics” gets thrown about a lot. And I understand how, from an advocacy perspective, this line of thinking is counterproductive and can be used as a rhetorical device to turn underprivileged groups against each other. But from a policy perspective, asking these kinds of questions is essential. Policy always involves making tradeoffs among finite alternatives – taking one approach can often mean not taking another, so you have to choose priorities and emphases carefully. There are lots of unearned inequities among different segments of people in this life, many of which have established places in national dialogue and many of which have not. Did you know, for example, that height is significantly correlated with earning power? On the strength of a study conducted for his book Blink, Malcolm Gladwell even claims that “being short is probably as much, or more, of a handicap to corporate success as being a woman or an African-American.” I’m not sure I’d go that far, but I do think it makes sense to try to identify and target leverage points that trigger lots of injustices at once. One of those leverage points might be socioeconomic class, given that economic security touches so many areas of life. In no small part due to the legacies of historical discrimination, race and class today are closely intertwined: white families are on average an astounding six times wealthier than black and Hispanic families. But this means that a strategy to address class inequities, which can benefit from some existing infrastructure in the form of progressive taxation, will have the benefit of addressing many (albeit not all) of the racial inequities as well.

- Can we stop talking as if there are only two sides to this story? Too many of the mainstream narratives about race in the United States are stuck in mid-twentieth-century paradigms of black vs. white. The classic archetypes of the oppressor and the oppressed make for good movies, but the racial groups that feature in conversations about race today are insanely reductive visions of reality. Hispanic/Latino makes lots of sense as a language-based subculture (superculture?), but it’s not an actual race even though we often talk about it as if it is. Arab Americans are considered Caucasian by the Census, but try talking to them about white privilege while they’re going through US Customs. Most African Americans are actually mixed race, and first-generation African immigrants often have little in common with descendents of American slaves beyond their skin color. There are Jewish Venezuelans and white Africans and black Dutch. People of color are not a monolithic group, and don’t always like each other; there is a long and ugly history, for example, of East Asian bigotry against black people. Nor do they face the same challenges: whereas the college graduation rates for African Americans and Hispanics are 20% and 14% respectively, Asians have been north of 50% since 2005. We are prone to equate gentrification with “white people taking over the neighborhood” but ignore the role that people of color play in that process. Even within the arts, we oversimplify the racial identities of our institutions, casually applying the adjective “white” to orchestras for example, in spite of a huge influx of Korean, Chinese and Japanese instrumentalists in recent decades. The anti-racist movement is fond of pointing out that race is an artificial social construct—maybe we should all start treating it like one?

- What is the role of assimilation in defining racial power structures? White people are not a monolithic group either. In the United States alone, there used to be bitter hatred towards ethnic Germans, rampant discrimination against Jews, and immigration restrictions erected against Italians, to name a few. What we think of as “white privilege” today was WASP privilege 100 years ago. What lessons can we learn from the dramatic cultural shift that has taken place in the meantime? And how much of a role has intermarriage between white ethnic groups (see below for more) had in making that shift possible? Moreover, does talking about white people as one group – since no white ethnic group would constitute a majority on its own – serve only to solidify the sense of whiteness as the majority default? In a long piece for the Grantmakers in the Arts Reader, Heinz Foundation arts program officer Justin Laing criticizes “the normativeness of White people’s arts and culture experience that is often implied when ALANA [African, Latino/a, Asian, and Native American] work is referred to as ‘culturally specific’ or ‘ethnic arts’ or ‘folk arts,’ as though White artists’ and arts organizations’ work is less specific, ethnic, or folksy.” Laing goes on to write, “This false idea, Whiteness, is maybe the most damaging of all of the race-based fallacies because it plants deep within us the idea that White people are both separate and the standard; it’s a particularly harmful idea in our field that treats the best of White culture as classical not only for Europeans but also for the world.” To what extent does the diversity conversation in the arts perpetuate the very inequities we’re trying to dismantle?

- How is demographic change going to affect the way we think about race? The United States will be a majority-minority country within 30 years. Four states – California, Texas, New Mexico, and Hawaii – along with the District of Columbia already hold this status. The vast splits between racial and ethnic groups in recent presidential elections remind us that in a democracy, having a baby is not just a personal decision, it’s also a political act. Of course, just increasing the numbers of brown people won’t necessarily lead to the end of white hegemony – see the early-20th-century South or mid-20th-century South Africa for proof of that. Perhaps more important, then, is the increasing trend toward multiracial families via adoption (especially by increasingly visible gay parents) and widespread intermarriage, both of which are and will continue to be facilitated by the growing numbers of non-white individuals in the U.S. Could this blurring of racial categories smooth over old tensions to the point that no one cares about them anymore? I wouldn’t discount the possibility, especially when you consider how much the drive towards acceptance of gay marriage has been driven by loved ones coming out as gay. The elevation of a mixed-race President may not signal a society that has moved beyond race, as some have over-optimistically claimed, but it may yet be a harbinger of America’s post-racial future.

- How committed are anti-racist white people to ending white privilege? This is an important point that I really don’t think we ever talk about. Merely recognizing that white privilege exists and feeling bad about it is not a recipe for change. Real change, all else being equal, must involve actual sacrifices on the part of those in power, with the white majority being the party in power when it comes to white privilege. Power is not necessarily a zero-sum game, but relative power is – and the privileged position in which white people find themselves in the United States is a result of the exercise of asymmetric power dynamics in the past. My questions for those who fancy that they would like to end white privilege are as follows: why don’t we ever talk about giving large swaths of land back to the Indian tribes who once occupied them, and whose value system is so rooted in the land itself? Why don’t we ever talk seriously anymore about reparations for slavery, the reverberations of which are still very much being felt today? (Such reparations would be hardly unprecedented, by the way.) Wouldn’t such things represent much more meaningful change than reminding oneself to make eye contact when one sees a person of color coming the other way?

- Would we be better off as a society if we were actually less conscious of race, not more? Even if that’s not the right or a realistic goal for the short term, is it what we should be working towards in the end? If so, how would that change how we approach conversations about race? In a 60 Minutes interview with Mike Wallace eight years ago, Morgan Freeman famously called Black History Month “ridiculous” and called for its dissolution. Wallace asked how we can get rid of racism otherwise, and Freeman responded, “Stop talking about it! I’m going to stop calling you a white man, and I’m going to ask you to stop calling me a black man. I know you as Mike Wallace, you know me as Morgan Freeman.” I imagine that many people reading this are familiar with the concept of priming in psychology – the idea that subtle stimuli can (often unconsciously) affect our behaviors and performance. There’s even a significant literature exploring the racial dimensions of priming; for example, one study found that simply identifying their race on a pretest questionnaire cut black students’ performance on GRE questions in half. Well, what happens when we continually prime white people to believe that they’re racist, and people of color that they are victims of racism? Does that in any way exacerbate the problem?

Introducing this sort of complexity into the equation may come off as an invitation to chaos. But think about it this way: would we be satisfied with a map of the world that just had the seven continents on it and a vague notation of which direction they are relative to each other? No, we do what we need to as a society to have hyper-specific geographic markers down to a few hundred feet, all connected, continually updated, existing within an ecosystem of other information like traffic patterns and mountain heights and vote totals.

I believe that the frame for our discussion must be both that large and that fine-grained in order to make real progress. On the large end of the scale, what do we care about most? Is containing racism, rather than ending it, acceptable? And if ending it is paramount, then is equality of opportunity sufficient for ending racism, or is equality of outcomes necessary? At the micro scale, who benefits and who suffers from racial constructs, to what extent and in what ways? In each case, down to the individual level, how much of that benefit or suffering is the product of socially-constructed and mutable ideas of race and how much is tethered to immutable realities of race? And what of those inequities are solely attributable to race rather than tied up in other kinds of disadvantage/privilege?

What can I say, it turns out that understanding and dealing with race is really hard! But I truly believe that only the hard work of identifying what our true values are and articulating how we resolve dilemmas when they come into conflict with other values can help us resolve the large-scale questions. And only the hard work of mapping out all of these intimidating complexities as they play out in individual lives will enable us to make the changes to our societal rules and behaviors that will end up serving the most people the most fairly. In fact, I don’t see how anything other than hard work, strategically focused, will make any difference at all. So let’s get to work.

*

(I am deeply grateful to Talia Gibas, Selena Juneau-Vogel, Daniel Reid, Hayley Roberts, F. Javier Torres, and Jason Tseng for their incisive comments on an earlier draft of this article, and to many others for their conversations and perspectives that helped expand my world these past nine months.)

Further reading:

- Andy Horwitz, Whites Only (Or, WTF is the Deal with Diversity in the Arts?)

- Maria Vlachou, The beginning and ending of a b&w week in Vienna

- Maria Vlachou, The new year

- Linda Essig, Diversity, Equality, Bus Lanes, and the Arts

- John L. Moore, III, Equity/Diversity/Change

- The Untenable Whiteness of Theater Audiences, discussion thread at MetaFilter

- Clayton Lord, Yes/And – tackling racial diversity by looking to things adjacent

- Clayton Lord, Carrying Forward, Clumsily (if you read one piece by Clay, I recommend this one)

- Jesse Rosen, Doing More About Diversity in America’s Orchestras

- Tiffany Wilhelm has put together a Google Document with lots of links to additional resources