From Baku to Bangui, Boston to Bangkok, we need a diverse, equitable world of cultural voices for our times. Createquity imagines that a healthy arts ecosystem is one in which opportunities to make one’s living as an artist are distributed equitably across socioeconomic levels. Unfortunately, that does not seem to be the case in many western countries, where research indicates that people of lesser means are not as equipped to take on the risk involved in pursuing a career in the arts.

Around the world, we see people facing challenges not only accessing careers as artists, but also sustaining them. South Korean artists make 77% and Canadian artists 74% of their respective countries’ average income. In Ireland, 80% of visual artists who depend on their creative income live in poverty. One survey respondent in that country describes the outlook for artists this way: “The future always looks worse than the past. Economic booms are quite bad for artists, because they can’t afford to live where they should for their careers. Busts are worse.”

Generally, people born into less affluence have to work harder to catch up in any field. The Guardian’s Sonia Sodha writes that “we’ll never be able to eliminate the role that good fortune plays, but we need to do much more to lessen its influence and increase the relationship between effort and success.” What role can government play in lessening the influence of fortune when it comes to supporting artists? A look at several countries gives us some clues.

Two Models: National Status vs. Sink or Swim

In some countries, including the United States, being an artist doesn’t necessarily mean having a professional artist career track, especially not in any sort of state-sponsored system. As one national study of artists reported, “some painters interviewed said that career was not part of their professional vocabulary; they simply were painters.” In that context, as we’ve explored, many US-based artists have day jobs and backup plans, and find themselves crossing between nonprofit and commercial sectors in a demanding market economy.

In other parts of the world such as in the former Soviet Union, as scholar Nina Dimitrialdi describes in her 2009 PhD dissertation on challenges faced by US and UK artists, “artist” was indeed a profession just like any other. An artist in the Russian Federation with “professional” status from the government currently receives compulsory social programs such as insurance covering illness, housing, maternity, disability, and retirement. Many countries with cultural sectors based on the old Soviet model, such as Egypt, fully bankroll training programs and manage “card carrying” artists and their benefits through a national union.

Left: Egypt’s High Institute of Ballet, 2013 (conditions under Presidents Mubarak, Mansour and Morsi) | Right: Same facility in 2016 (under President el-Sisi) – Images by Shawn Lent and Madga Saleh

Whether or not artistry is a formal profession in the eyes of the state, and what states do or don’t do to support that profession, reflects different agendas within different political systems. While the American model mostly distributes public funding for the arts indirectly, via tax deductions for nonprofit organizations and their donors, many other governments provide substantial direct support to individual artists. Increased overall government funding for the arts could be an important indicator of potential support for economically disadvantaged artists, but there is an opportunity in cultural policy to assess what funding schemes help bridge wealth gaps in the profession.

Unfortunately, we found existing research on this topic to cover predominantly North American and European countries, with few nationally representative results relating to artists from poorer backgrounds. While it is difficult to get a good read on the situation internationally, in many parts of the world, it does appear that dedicated government support – in the forms of subsidies and other incentives – has opened the artistic profession to more people across social classes.

Public Policy Can Keep Artists Afloat

We see a number of countries enacting support programs for artists that are tied in with their tradition of centralized social services, supporting the basic needs of all citizens; this could be critical for artists and similar types of workers. As Quartz’s Aimee Groth put it when speaking about entrepreneurs, “when basic needs are met, it’s easier to be creative.” By giving more of a safety net to artists born with less means, government programs can make it easier for people (artists included) to risk being “entrepreneurial.”

Slovenia, Finland, Italy and Austria are a few of the many countries that offer pension and retirement programs to deserving artists as defined by those governments. The South Korean Artists Welfare Act extends the country’s employment insurance to 180,000 artists and accident insurance to 57,000 artists. The Danish Arts Foundation’s life-long benefit grants (livsvarige statsydelser) are awarded to state-selected, high-achieving artists in that country. In Thailand artists employed by the Ministry of Culture are considered civil service officers with the same salary system and benefits, and in Germany, the Artists’ Social Insurance Fund (Künstlersozialkasse or KSK) has been supporting self-employed artists and journalists since 1983.

2009 Making an appointment with Sabine Schlüter, head of KSK (Künstlersozialkasse) – Photo by Flickr user, Henning Krause

Estonia

Another country advancing its support of artists is Estonia, where a select group of artists and writers are offered a €1005 salary per month for two years plus health insurance and a pension plan. According to Indrek Saar, Estonia’s Minister of Culture, “the purpose of [the program] is to offer for a couple of years a possibility to work in peace and social guarantees for the distinguished creative people. Economic stability of a creative person gives better preconditions to create a new work of art.” This year Saar announced a 13.5% raise to the minimum wage for cultural professionals in that country’s government. This program is quite similar to one in Sweden, where income guarantees are given to selected artists who have created work considered “important for Swedish cultural life.”

Netherlands

The Netherlands has historically been a strong leader in this realm. The Dutch Artists’ Work and Income Scheme Act (WWIK), in place from 2005-2012, was the third major artist subsidy program developed for the country. WWIK provided financial support (70-125% of the guaranteed minimum income) for artists with a low income for a maximum of 48 months over 10 years to cover the start-up period of their professional arts career. Dutch artists also received extensions in the availability of unemployment benefits (4 years rather than 6 months).

While that program did not track impact for artists from financial disadvantage, another example from the Dutch attempted to connect cause and effect. From the 1960s-80s, the Netherlands provided temporary assistance to low-income visual artists that allowed those artists to sell their work directly to local governments as a supplement to income. The number of participating artists increased from 200 in 1960 to 3800 in 1983. During the same period, the growth rate of student enrollment in fine arts departments at Dutch academies was 60% higher than the average growth rate for technical and vocational training in other fields.

Members of Ethiopia’s Ras Theatre group dance and play as they wait for Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni at Bole Airport, Addis Ababa – Photo by Flickr user, Andrew Heavens

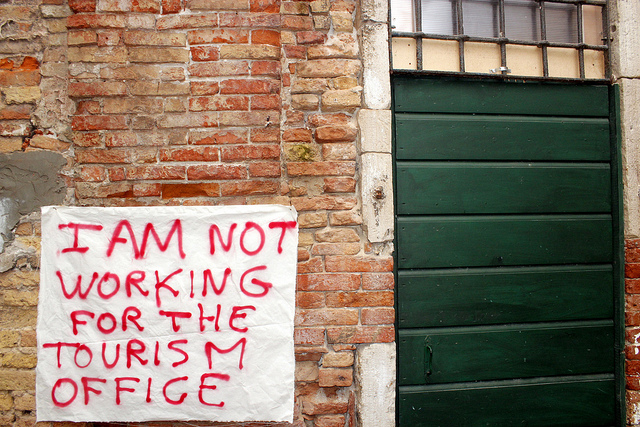

The Warning: Selling Out (or Buying In) for Survival

Governments sponsor artists for a complex set of purposes: cultural tourism like the kind Russia is planning in occupied Crimea; income generation or nationalism such as with the Agencia Cubana de Rap in Cuba; protecting the national image like in Vietnam; “preserving the country’s national cultural assets for the benefit of all citizens and future generations” including aboriginal arts like in Canada; binational collaboration such as that of China-Moldova; cultural diplomacy, placemaking, or improving public morale. Generally speaking, state-sponsored artists are expected to adhere to policies that align with national interests.

Before we all make a rush on the Dutch consulate or start demanding new state-sponsored artist programs in our respective countries – quite the issue to float in our current political climate – it’s worth considering the pitfalls that can come with increased government involvement in the arts.

- Threats to Freedom of Speech: Several of the programs mentioned above are or were careful to allow artistic freedom. The Netherlands supported the artists participating in its assistance programs regardless of the style or content of the work they produced. In Estonia, Minister Saar explains that artists receiving the government salaries are “still free in their creative work; the only requirement for the creative person is the commitment to one’s creative work.” Unfortunately, such freedoms are the exception rather than the rule. Many countries, such as Zimbabwe, have a national agency for censorship. While increased government support for artists can result in great technical rigor in the respective art forms, like in Russian ballet, it can also mean stringent restrictions on artistic expression and a high level of government interference. In 1980, UNESCO recommended governments “determine those remunerative jobs which might be confided to artists without restricting their creativity, their vocation and their freedom of expression and communication.” Russia may recognize artistry as a “profession,” but its track record with creative expression is abysmal; the organization Freemuse registered 32 attacks on artistic freedom in that country (such as censorship, imprisonment, physical attack, and death) in 2015 alone.

- Questions of Scale and Dysfunction: Government funding artists doesn’t automatically result in a net benefit for all individual artists, let alone poor artists. Many of the programs we came across focused on a relatively small number of superstars. Can any of these programs run at the scale needed to address the flaws in our arts ecology? And at what point might increased scale mean increased risk of corruption? Would an international scheme across the sector be more effective than relying on individual polities?

- Risk of Perpetuating Cultural Inequities and the Residual Effects of Colonialism: We have been examining government programs from the perspective of reducing socioeconomic inequality in the arts ecosystem, but in fact artists who are LGBTQ, with disabilities, from marginalized racial or religious groups, or political opposition may be just as likely to be excluded from government programs in many countries. With decision-making about which artists to cultivate via government sponsored programs so centralized, states have few incentives to include groups that may be at odds with perceived government interests.

- Risk of Servile Labor: Similar concerns apply to arts disciplines and new forms of self-expression. If you pursue a career as a painter of socialist realism art because the government only supports and allows that form of art, then there are fewer opportunities for you to express yourself and for audiences to gain benefits from a variety of artistic expressions. Artists in North Korea have been exported to execute massive arts projects in countries such as Cambodia, hired as employees to earn hard currency for the State.

- Lack of Cultural Variety: Even when a government’s intentions are pure, it is not clear that placing decisions about artists’ careers in the hands of bureaucrats leads to the best possible mix of cultural products and experiences. Generous benefits for artists in all likelihood means a limit on the number of artists who can access those benefits, which may mean that the people left out have even fewer opportunities to have a public creative identity and get paid for it. For all its issues, the United States’s market approach is rarely criticized for yielding a boring, homogeneous mix of work.

Government policies can make it possible for artists to pursue better, more dignified careers, but there is no such thing as a free lunch. As we move forward in addressing the questions of support and equal opportunity in arts careers, we must be conscious of the tradeoffs inherent in systems that rely on more overt government or other patronage of the arts.

In the latest Createquity podcast series, Createquity and Fractured Atlas team members illuminate the major factors that contribute to artists (or prevent artists from) establishing successful careers. We also focus on some of the tools Fractured Atlas has developed to support artists, with the larger goal of helping create a more navigable and equitable ecosystem for professional artists.

Cover image: “Radical – Avant la Tempête @ EDLD 2015,” courtesy of Flickr user, Duc, via Flickr Creative Commons license.