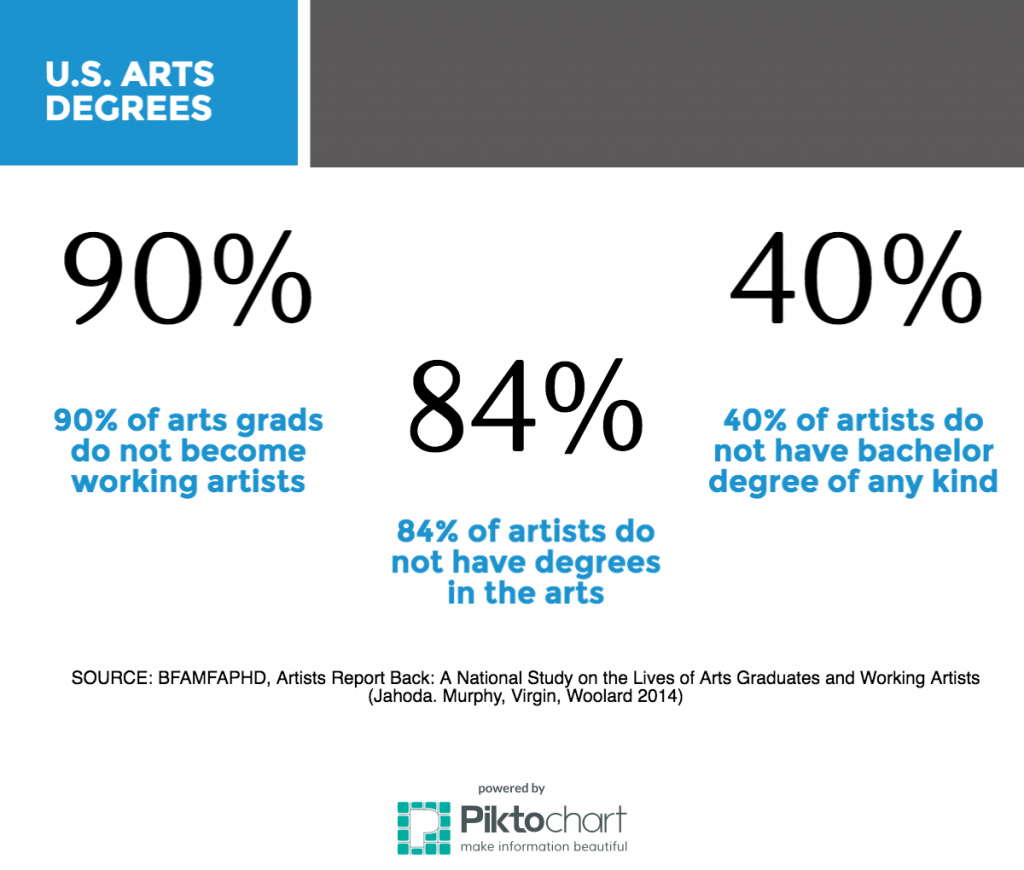

‘Tis joyful commencement season. If you took home a diploma for a four-year degree in the visual or performing arts last weekend, you’re not alone: in the U.S., more than 91,000 college graduates are venturing out into the world with BFAs or their equivalent in hand. They are more likely to be from upper and middle class households than grads from other majors, with an average family income of $94,381. Only about 10% of them, if one report is to be believed, will actually become full-time professional artists.

In “the real world,” 84% of working artists—defined by BFAMFAPhD’s controversial “Artists Report Back” study as people who make their primary living from their artwork—do not have degrees in the arts, and 40% have no college degree at all. (It’s important to note that due to data limitations, these figures exclude artists with master’s degrees or beyond in any field; however, the number of artists affected is relatively small.) If arts training programs continue to climb in popularity while budding artists from less affluence are deciding against studying the arts in college, does that mean the college-to-career trajectory is a myth? Has the arts degree become a luxury, or are artists from less advantaged backgrounds missing out on something?

Graphic by Shawn Lent for Createquity. Source: Artists Report Back

An Incubator of Artistry or a Waste of Precious Prime Time?

What can we make of the implication that higher education is not the golden ticket to creating or performing art for a living? It would be overstepping to say that arts degree programs provide students with no value at all: for one thing, they offer important time to refine one’s craft within a supportive but highly disciplined and similarly-skilled community of peers, critical mentors, and potential networks. Such credentials can serve as a signal of high artistic quality and capacity, a prerequisite for certain grant funding. We should note, though, that artists move freely between the nonprofit and commercial sectors in their pursuit of paid work and the value of a degree likely varies by context. It looks like a person doesn’t necessarily need a BFA or MFA to become a professional artist, but the degree could help an artist reach a higher level of industry success or make a full-time living as an artist.

At the same time, arts students may not have this expectation of working as artists. Across the board, most graduates (73%) work in a field outside their major. Arts students, in particular, might be prepared to thrive in other sectors, and they seem fine by that; the ongoing Strategic National Arts Alumni Project survey (which likewise has its limitations) finds that arts graduates are generally satisfied with their experiences and would do it again if they had the chance.

B.A. and Arts Double-Majors at Commencement 2016, UMD School of Theatre Dance and Performance Studies | Photo by Karen Kohn Bradley

For pro artists, the necessity or desirability of arts degrees may vary considerably by discipline. Although full-time symphony orchestra musicians are selected by audition, it is hard to find one these days without a degree in music. On the other hand, from the Oregon Ballet to Bally’s Jubilee, dance artists often delay or skip college because of the early retirement age in most dance forms (90.5% of working dancers and choreographers are under age 40, compared to 39.6% of working musicians). Examples like these leave arts degree programs vulnerable to the charge that they are building up a profession (academia) that isn’t necessarily serving artists. Sarah Anne Austin questions, “If opportunities in American modern dance are disappearing, and if being a tenured faculty member at a university is the only stable job available for dancers and choreographers, and having this job depends on being able to attract students… does this make American modern dance a pyramid scheme?”

One Option in a Long Line of Pricey Career Strategies?

Such questions wouldn’t be so charged were it not for the very real concern that arts degrees perpetuate inequality in the sector. Professional artistry has a lengthy and complex gestation period that is slammed with socioeconomic obstacles. Factors that may make, or break, one’s professional success as an artist include personal networks, the prestige of the teacher, portfolio materials, membership in a union/guild, affordable housing in a city with available arts jobs, and a myriad of other opportunities such as showcases, apprenticeships and internships.

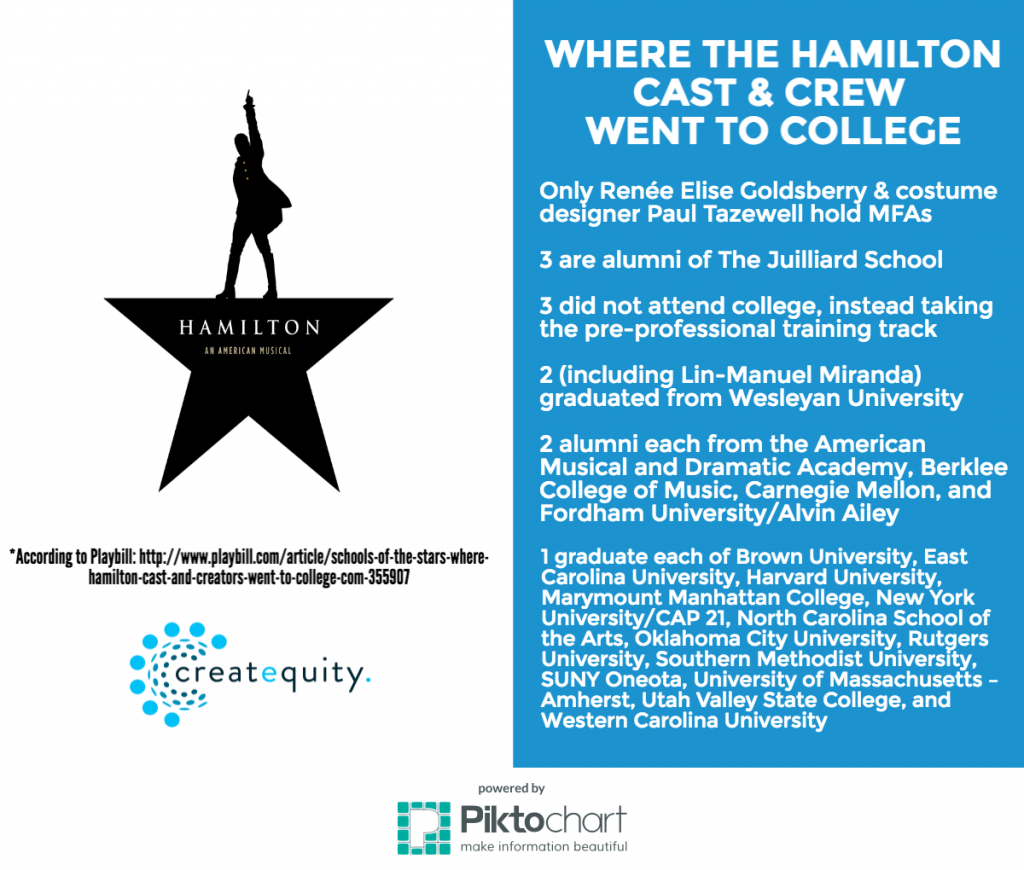

Graphic by Shawn Lent for Createquity. Source: Playbill

Like aspiring athletes, emerging professional artists benefit from school and community members who identify and develop their interest, regular and rigorous private lessons, and pre-professional training. These present quite the financial hurdle for families: a recent calculation estimates that it takes $100,000 to raise a professional ballerina. Against this backdrop, the cost of college may only exacerbate what is already a yawning opportunity gap.

The Greatest Risk or the Great Arts Equalizer?

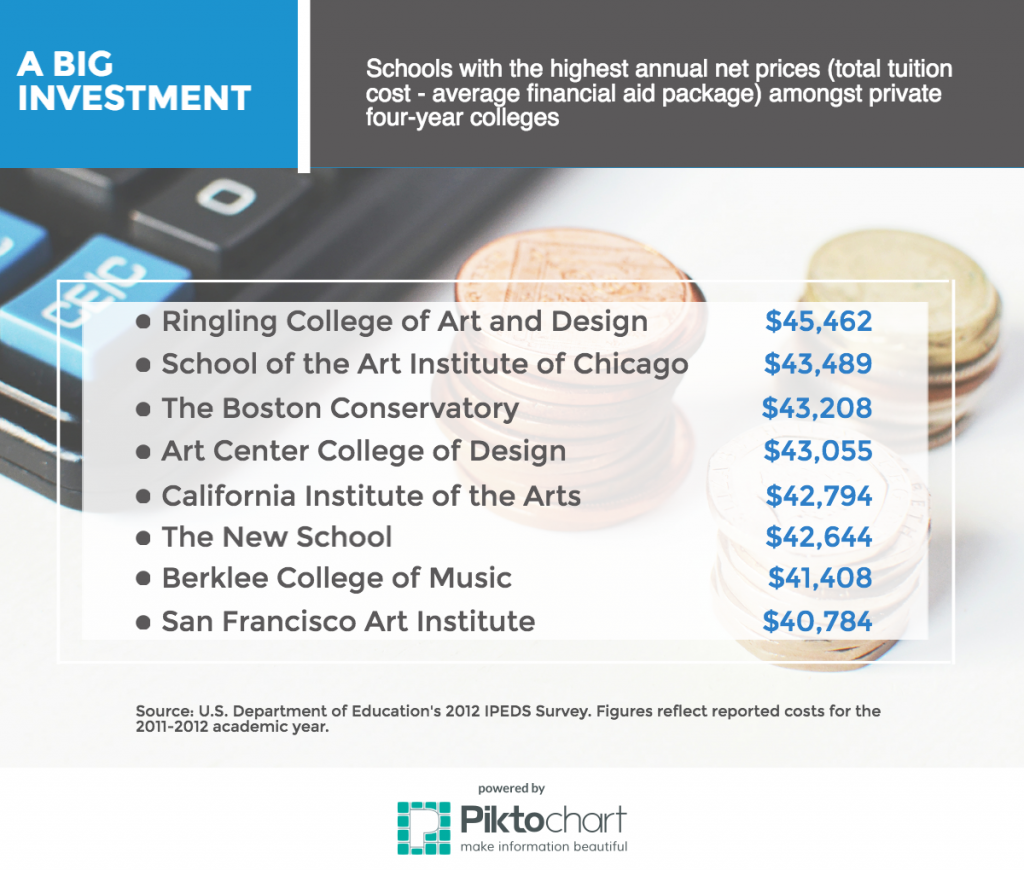

We may not know definitively whether arts degrees provide added value to aspiring artists, but we do know that they pose quite a bit of risk, particularly for artists coming from low socioeconomic status (SES). Although artists with bachelor’s degrees in any major earn more than artists who went pro after high school, new BFA holders quickly face the reality that artists experience lower returns to formal education than they would in other professions. Anywhere from 10-20% of artists with bachelor’s degrees report a “major impact” on their career decisions due to debt from higher education; this debt load comes on top of a heavy earnings penalty across the board for artists (8.4 percent lower than the rest of the labor market, according to 2000 Census data).

Graphic by Shawn Lent for Createquity. Source: U.S. Department of Education IPEDS Survey

Particularly on a discipline-specific basis, the conditions leading up to the decision to pursue professional artistry may represent disparities of access. If it were the case that high school graduates who aspired to artistic careers couldn’t pursue their dreams because of the risk aversion associated with low SES, that would be a major failing of a healthy arts ecosystem.

Given that, it’s probably a blessing in disguise that you don’t need an arts degree to become an artist. In fact, the preponderance of upper-middle-class students in programs offering those degrees might well indicate that poorer, emerging artists are making informed decisions that are in their best interests. Everyone’s situation is different, and statistics can only tell us so much about an individual case. But if you’re worried that an expensive four-year degree is your only way to the top of the arts heap, you can take heart in the knowledge that many, many creators and performers have made it there without one.

In the latest Createquity podcast series, Createquity and Fractured Atlas team members illuminate the major factors that contribute to artists (or prevent artists from) establishing successful careers. We also focus on some of the tools Fractured Atlas has developed to support artists, with the larger goal of helping create a more navigable and equitable ecosystem for professional artists.

Cover image: “Hiram College Commencement 2015,” courtesy of Kasey-Samuel Adams via Flickr Creative Commons license.