One hot August day last summer, my Facebook news feed suddenly blew up with frustration directed at New York Times fact-checkers, editors, and writers over the geekiest of subjects: data quality. The complaints were coming from friends of mine associated with the Future of Music Coalition, frequent commentators on policy affecting musicians in particular and creators of all kinds. These are two brands that I respect enormously – the Times website gets multiple visits from my browser a day, and FMC puts out some of the best policy analysis out there – so of course I wanted to find out what all the fuss was about.

Remember the fierce debates that gripped the music industry when pirated MP3s started popping up on filesharing sites like Napster and Audiogalaxy? On one side, copyright defenders fought these sites tooth and nail, even to the point of suing individual users, in an unsuccessful effort to stem the tide. On the other, copyright reformists and anarchists embraced filesharing as a way of bypassing traditional gatekeepers. To bolster their position, the old guard frequently adopted doomsday-like language predicting the death of the music industry and the loss of artistic vitality. The new guard argued the opposite, contending that piracy was essentially free marketing for artists, and that if anything the increased exposure and attention would facilitate connections (and transactions) that would not have previously been possible.

So who was right? A cover story published last year in the New York Times Magazine by noted business and technology writer Steven Johnson would have you believe that piracy has turned out to be no biggie for artists and society. The article, entitled “The Creative Apocalypse That Wasn’t,” attempts to explore how “today’s creative class [is] faring compared with its predecessor a decade and a half ago.” (Johnson and his editors at the Times annoyingly use a different definition of “creative class” than Richard Florida, who originated the term—they specifically mean people who work in entertainment industries.) To do this, Johnson examined a raft of secondary data sources to assess everything from the size of the industry to average incomes to aesthetic quality.

Despite evidence that Napster and its successors have indeed undermined the value that consumers place on recorded music (annual revenues have declined from $60 billion to $15 billion worldwide), Johnson’s analysis finds that musicians, along with writers, directors, and other performers, don’t seem to have suffered greatly as a result. To support his contention, Johnson cites data from three sources that collectively show creative industry jobs, businesses, and incomes growing in relation to the rest of the economy between the turn of the millennium and 2014. He considers possible macro explanations for the trend, including declining costs of production and distribution and increased revenue from live music performances. He even attempts to address the quality of different disciplines over the time period, concluding that TV is in a golden age and that film and books are arguably no worse off than they were before. Far from harming the diversity of artists’ voices, according to Johnson, technological change has enabled it.

The article immediately provoked an intense backlash from artists and industry representatives alike, many of whom didn’t see their story represented in the data. The most thoughtful broadsides came from Future of Music Coalition, which pointed out that the case that artists and musicians have not suffered economically over the past 15 years relies heavily on the data from the federal government’s Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) and Economic Census, both of which turn out to be compromised. By the government’s own admission, OES is not an ideal data source for making comparisons over time, and some sleuthing by FMC and Thomas Lumley pinpointed a definitional change that appears to account for all of the growth reported in the number of musicians and then some. Meanwhile, according to Patrick Wang, general definitional fuzziness may be distorting the numbers of all creatives as well, with coaches, scouts and public relations specialists accounting for much of the growth seen in those statistics. Johnson’s article also neglects to mention that the number of artists employed by businesses, as reported in the Economic Census, has dropped—even though the number of businesses employing artists has grown. And there are a number of reasons why some of the more secondary elements of “Creative Apocalypse” (e.g., the analysis of the growth of live touring revenues) need to be taken with a grain of salt as well.

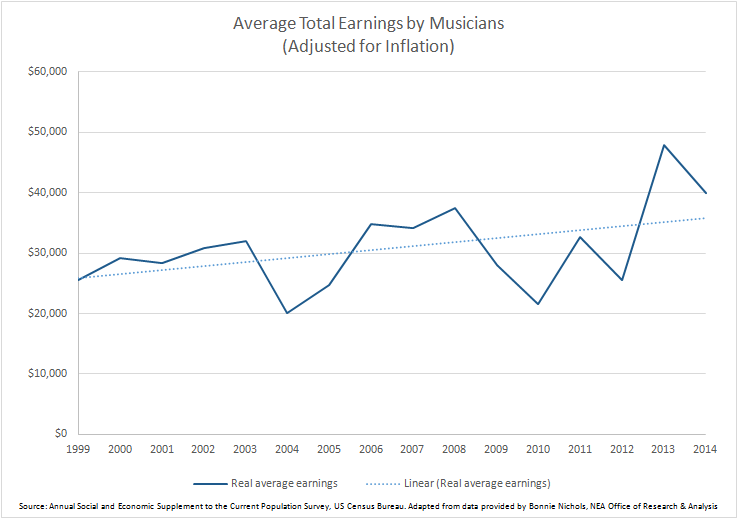

These are significant flaws, and it’s perplexing that Johnson’s editor at the Times, Jake Silverstein, persisted in calling the article “excellent” and “thoroughly researched” even after they were brought to his attention. That said, when a data source turns out to be suspect, it doesn’t always mean that the conclusion you were drawing from it is wrong. In November, the research team at the National Endowment for the Arts took another look at the issue through the lens of an entirely different data source: the US Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey. Unlike the OES statistics, the CPS is set up to be analyzed longitudinally, and there are no changes in how “musicians, singers, and related workers” have been defined over the past 15 years to muck up the analysis, making it a much better data source for this purpose.

The CPS data shows that the percentage of musicians in the workforce has remained largely stable over the time period, splitting the difference between Johnson’s article and the revised analysis offered by his critics. More importantly, the CPS data shows musicians’ real incomes rising substantially, and faster than overall workers, during the time period in question, albeit with substantial variance from year to year. (This had already been the strongest part of Johnson’s analysis – as he correctly pointed out in a response to one of the critiques, no one has been able to point to a data source that has musicians’ average incomes declining since 1999.)

So it looks like there has been some growth among creative fields, music included, in the past decade and a half. Why, then, does it feel to so many like the profession is in crisis? After all of this analysis, the biggest unanswered question is about the distribution of the growth. When we write a sentence like “musicians’ income has increased,” the mind immediately conjures a picture of a rising tide lifting all boats. But what the data is really saying is that the average of all musicians’ income has increased – which could mean that a few fatcats making a killing are disguising stagnation or worse for everyone else. In the original article, Johnson makes a weak case that this is not happening, using incomplete data on live music tour revenue only; however, in one of his follow-ups, he claims that he looked at median income for musicians, which has—surprise surprise!—outpaced the growth in average income during the years from 2004-2014. But before we get too excited about this, keep in mind that this analysis used the same flawed data set as had been discredited earlier, and the same challenge that skewed the numbers there (dumping a bunch of elementary and secondary schoolteachers into the mix midway through) could quite plausibly have affected the income figures too. Johnson’s rhetoric implies that all artists are sharing in the largesse, but if income inequality is increasing, that would be like touting America’s shared prosperity on the basis of stock market growth since the depths of the recession.

Another clue to explain the reaction to the article comes from the NEA’s response, which pulled the figures on real investment in new music between 1999 and 2014 from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. In contrast to movies, television programs, and books, which have seen steady or increasing investment over that time period, annual investment in new musical intellectual property products has declined an astounding 28% in inflation-adjusted dollars. The decline in recorded music revenues likely has a lot to do with that.

Overall, the picture being painted in the data (that we can trust, that is) is one of the same number or fewer people identifying as full-time professional musicians, but making more money on average. But as anyone who follows the music industry knows, that misses a significant part of the story. Thanks to technological changes that have made the means of music production and distribution cheaper and more accessible, it seems like a good bet that there are lots more people who are pursuing public identities as musicians today than there were in 1999. If that’s the case, but yet there are not more people able to make a living as a musician, it would mean that a data set that captured all aspiring musicians might well show average incomes going down.

So, back to Johnson’s premise: are we better off than we were pre-Napster? It depends on your perspective. There is still plenty of money to be made in the creative industries, and Americans are still as willing to pay for entertainment as ever, although the specific mix of goods and services is changing. But if you’re a creator who works primarily in music, it does seem like opportunity might be shrinking. So far, it doesn’t look like the decline in recorded music revenues due to streaming and piracy has spread to other industries and genres, but it’s unclear whether film and TV are being buoyed by shifting audience preferences or have simply managed to stave off a similar collapse that is coming soon.

Meanwhile, we’re left with the plight of the artist. In recent decades, researchers have found that one of the surest paths to unhappiness is to have expectations that go unfulfilled; Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman writes in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow of a study that showed that “measured by life satisfaction 20 years later, the least promising goal that a young person could have was ‘becoming accomplished in a performing art.'” It’s tempting to interpret the increase in access that technology has provided to aspiring artists of all kinds as an unqualified boon for society. But to the extent that the opportunity to have a public identity as an artist has translated to expectation of public success as an artist, we may be looking at a system that, in the aggregate, punishes people for pursuing their dreams – a creator’s curse of sorts. If true, that issue goes way beyond how Pandora and Spotify divvy up their royalties and whether Apple Music gives sweetheart deals to Taylor Swift. And part of the answer may lie in helping aspiring artists make more informed decisions about how much of themselves they’re really willing to give up for art.

Related reading: