Entry to the Kennedy Center for the Arts. Photo courtesy of Adam Fagen.

While living in China, I befriended a Japanese classmate who spoke no English. I spoke no Japanese, but we both spoke Chinese—and more importantly, we both played guitar. Our connection to music served as the foundation of friendship. She taught me to play Japanese rock songs, and I memorized the lyrics to harmonize with her. Years later, I stayed with her family in Hiroshima and learned Japanese well enough to correspond with her via email. Along the way, I also amassed nearly 24 hours of Japanese music which I share with others every chance I get.

This was one of my many experiences with informal international cultural exchange since first venturing abroad after college. International arts exchanges reflect centuries of artistic exploration and the possibilities of an increasingly interconnected world. They can come in a variety of forms: formal or informal, undertaken by individuals or organizations, funded by private foundations or the government. This article examines how the more formal of those models have come to exist and the ways they are supported. (Note: while not all cultural exchanges can be considered arts exchange, for the purposes of this article I will use the terms interchangeably.)

Funding and Context for International Exchange

International cultural exchange’s long history is intertwined with the history of trade and conflict. Since the end of World War II, formal exchange initiatives and policies in the United States have been directly tied to the prevention of and recovery from international conflict.

In 1945, Senator J. William Fulbright proposed that surplus from the sale of war property be used to support educational, cultural, and scientific exchange, arguing nothing could better humanize international relations and promote goodwill among countries. The Fulbright Program, the State Department’s flagship international educational exchange program for students, scholars, professionals and teachers, was born a year later. The program was designed to promote mutual understanding between countries and work toward meeting shared needs. In 1961, the Mutual Educational and Cultural Exchange Act led to the creation of the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (BECA) under the US Department of State to oversee government funded international exchange programs. Today, the Cultural Programs Division of BECA awards grants to individuals and organizations through 46 discrete grant programs, about a third of which are related to the arts such as DanceMotion USA, American Music Abroad, and smART power. Grantee organizations may also solicit funds from the BECA directly for international project expenses, or seek funding from an independent nonprofit whose pool of money for funding exchange comes from the US government.

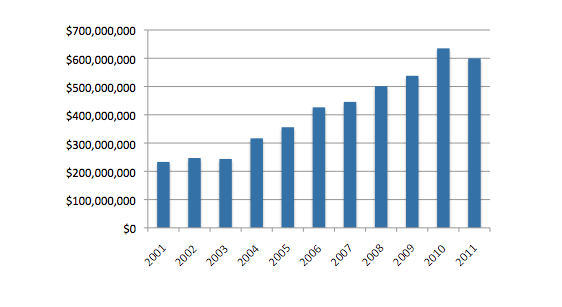

After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, government funding for cultural diplomacy weakened. But a decade later, shaken out of a false sense of amity by 9/11, the federal government reaffirmed the diplomatic value of international exchange by nearly tripling BECA’s budget from $233 million in 2001 to $600 million in 2011.

Source: US Department of State

Source: US Department of State

Figure 1 Government support for international educational and cultural exchange from 2001 to 2011

As government support for international exchange has waxed and waned since the end of World War II, so has private foundation investment, which has declined in recent years. The Robert Sterling Clark Foundation’s 2008 look at trends in international arts exchange giving shows a drop in foundation support from the heyday of the 1990s, when arts exchange funding made up 1% of total arts giving by major funders.

Despite inconsistent funding streams, a number of factors make international exchange programs more relevant today than ever before. Demographics are changing and international partnerships may help arts organizations engage new audiences. As the arts sector around the world professionalizes, we can learn from international counterparts’ approach to their work and vice versa. New learning theories and a better understanding of the creative process leave us primed to grow by crossing national and intellectual borders. To top it off, technology has made exchange across disparate parts of the globe easier. If a 21st-century citizen is a global citizen, arts organizations must begin to see how their work can and does transcend their immediate surroundings and seek integration into a larger, richer community.

This doesn’t mean they have to send staff on the next available flight to India to bring back tablas for inner city youth. International exchange is only meaningful insofar as it aligns with organizational mission. With exchange encompassing a seemingly limitless range of activities, examining what’s being done and done well can offer valuable lessons. The examples below offer a sampling of approaches to international exchange, with varying objectives, lengths, and target audiences.

Models

International Collaboration as Mission

Some organizations’ missions give preeminence to international exchange and build all activities around it. The Silk Road Project, for example, has international collaboration written into its DNA. Musicians from over 20 countries perform with and compose for the Silk Road Ensemble. Blending musical traditions from different cultures, they experiment with the creation of new music for their unique makeup of instruments and engage artists and audiences in the United States and abroad by raising awareness of different musical traditions around the world. With funding from corporations, the government, foundations, and even Sony Music, Silk Road’s education programs extend the benefits of their multinational and multicultural focus to provide “a gateway to greater understanding of the world” for youth.

International Youth/Artist Collaboration

I first heard of the Battery Dance Company when the ensemble was in Bangkok last year working with young hip-hop dancers as part of the Dancing to Connect (DtC) program, sponsored by the US Embassy in Bangkok through funding from the Department of State. Through DtC, Battery Dance Company teaching artists travel overseas to work with young dancers for a week, collaborating on original modern dance choreography that culminates in a joint public performance. DtC has put on programs in 25 countries to date, and trains outside teaching artists in its methodologies through the Dancing to Connect Institute. International work has become so central to its work that the company is putting together a resource on cultural diplomacy. Funding sources for DtC vary, with the Battery Dance Company often receiving in-kind corporate sponsorship for airfare or accommodations.

International Community/Community Collaboration

While DtC asks professional dancers to work with amateurs, Museums Connect asks museums to facilitate exchange between their peer communities. A BECA grant program administered by the American Alliance of Museums (AAM), Museums Connect brings together museum audiences with similar interests in disparate communities using a matchmaking tool provided by AAM. The process is reminiscent of online dating: museums first submit an organizational profile and collaborative project ideas to AAM. All profiles are posted online, allowing each museum’s project coordinator to browse for institutions with similar or intriguing project ideas, missions, or audiences. Project coordinators then reach out to prospective partner museums; if both sides agree to the “match,” they craft a grant proposal focused on connecting their respective audiences around a topic of common interest. If funded, proposed collaborations play out through a range of practices carried out by the participants in pre-identified groups from within the museum’s larger community that include but are not limited to travel, shared online prompts to spur artistic work, conference calls, and virtual exhibits. After the infrastructure for collaboration is set up, the communities take over the project.

The matchmaking process is critical to Museums Connect’s success, as these ambitious projects, which typically run over the course of a year, could easily stress institutions with limited capacity, particularly those in foreign countries.

International Institution/Institution Collaboration

One standout example that seeks to build capacity and inspire creativity over a longer period of time comes from the Netherlands’s Tropenmuseum and Indonesia’s Gajda Mada University. The Tropenmuseum’s parent organization and main source of funding, the Royal Tropical Institute, specializes in international and intercultural cooperation, leaving the museum well poised to take on a number of international partnerships. In the case of Gajda Mada University, the Tropenmuseum is helping to establish a graduate museum studies program, not by building a satellite museum, or committing staff as permanent full-time lecturers, but by building local capacity. Dutch museum staff and local Indonesian professors collaborate over five years, with Indonesians taking increasing ownership of the program over time. The strength of this model is its potential to add value to cultural institutions across Indonesia. The Tropenmuseum’s extended engagement allows its staff to build long-term relationships in Indonesia and tailor its support to local needs.

Considerations

We all feel we’re better musicians as a result of the Silk Road Project. We were taken to musical areas we didn’t know well, and have widened our own musical worlds. We have more tools with which to express ourselves. Most importantly, I feel more human, more connected to others. – Yo-Yo Ma

These examples offer entry points for even small organizations to mobilize themselves toward international work or think more globally in the creation of programs. In moving forward, arts organizations should keep a number of things in mind:

- Design exchanges with an eye toward mutual success. In order for exchanges to work, both parties must be able to clearly articulate how they benefit from the arrangement.

- Exchange requires resources. Any articulation of benefit requires a realistic picture of the level of engagement appropriate for each organization. Existing available time and capacity must be taken into account for fear of compromising quality.

- The impact of the exchange may not be uniform. Because partner communities and organizations start at different point from which “progress” is measured, each side may define impact differently.

- No matter how sexy the opportunity, exchange must align with mission. Underestimating the importance of institutional fit can derail even the most interesting programs.

The kinds of exchanges possible today extend far beyond the goodwill-building for conflict resolution and avoidance imagined post-World War II. As noted in the Rapporteur’s report on the 2012 Salzburg Global Seminar on public and private cultural exchange-based diplomacy,

The more autonomous and intertwined global cultural discourse of our day [is one in which] exchanges are not a corollary of state power, however soft and benign, but where transnational cultural interactions can constitute a “third space” of vibrant creativity—a realm of curiosity, meaning, collaboration, enterprise, and learning that is not directly beholden to either political or commercial interests.