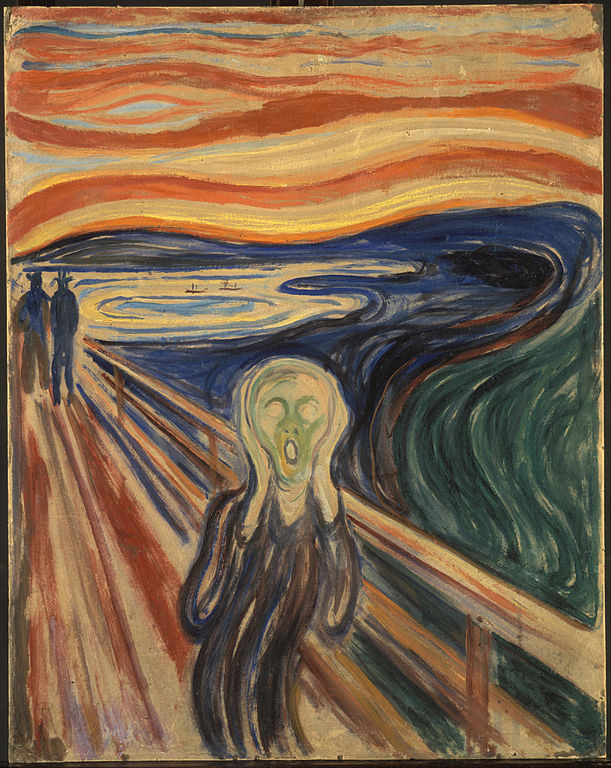

Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893) was stolen along with his Madonna (1894) from Oslo’s Munch Museum in 2004. After the theft, the combined value of the artworks was assigned retroactively at $121 million.

Christie’s auction house is wrapping up four months of appraising artworks at the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), which has become an unfortunate hostage in negotiations between the bankrupt City of Detroit and its creditors. When the city’s Emergency Manager, Kevyn Orr, brought in Christie’s in August, there was an outcry of disapproval from the public and museums across the country. Marion Maneker of Art Market Monitor described the general sentiment this way:

If you allow Detroit to appraise its art… you’re simultaneously devaluing the importance of art and culture and opening the door to further kleptocratic appropriations from the “public trust.”

Orr has said that he expects the DIA to find a way to raise money from its collection, which may mean a sale of some works at auction. However, the objections are not just to potential deaccessioning (the controversial practice of selling of a work in a museum’s collection), but even to the very notion of assigning an estimate of market value to works of visual art. Maxwell Anderson, Director of the Dallas Museum of Art, compared Christie’s process to “the weighing of souls” and expressed concern that it would “alter…the public’s perception of artworks from being ciphers of public heritage of transcendent value, to objects for sale to pay other people’s debts.”

Protests against the valuation of art in public institutions are not new. Once an artwork has made it behind the pearly gates of a major museum, it is generally considered to be off limits to market forces forever, preserved and protected for the benefit of all. The arguments for this view usually echo the opinion that art’s intrinsic and cultural importance render it priceless, so assigning a price would profane this sacred value.

But are these fears of assigning dollar amounts to artworks warranted? As an associate in the field of fine art appraisal, I take issue with the notion that art could be kept separate from economic value and market forces, even if we would like it to be – and I question the underlying belief that assigning price and respecting “transcendent” cultural value are mutually exclusive. As one municipal bankruptcy expert asserted, “You can’t pretend the art doesn’t have monetary value.” I would go further and say that we should be glad it does.

How Much Is It Worth?

The systematic valuation of artworks in a major museum’s collection is unusual. Even in the DIA’s case, Christie’s is only appraising a select group – less than 5% of the collection – comprised of works purchased directly by the City of Detroit. However, art museums, their collections, and exhibitions have always been intertwined with the art economy. Deaccessioning is one obvious point of intersection, but even setting the sale of art to the side, museums actually assign market value to works all the time, particularly when they acquire or loan them out.

A museum typically acquires work either through a direct purchase made with a combination of its own money and donor funds or via a donation from a private owner. In both instances, the artwork enters the collection with a price attached. In the case of a purchase, curators will examine the historical and aesthetic importance of the artist and her past market activity to justify to their director and board the need to spend a certain amount on a new acquisition. In fact, rising market prices for a less established artist’s work can actually be a signal that she is worth considering for acquisition in the first place. Pop over to the website for Boston’s Museum of Fine Art for an interesting peek at one museum’s acquisition policy (and visit it again for more insights on provenance, which we’ll get to in a bit).

In the case of a charitable donation to a nonprofit institution, the Internal Revenue Service requires that the artwork be professionally appraised upon acceptance to determine its fair market value, defined as:

The price that property would sell for on the open market. It is the price that would be agreed on between a willing buyer and a willing seller, with neither being required to act, and both having reasonable knowledge of the relevant facts.

This valuation provides the basis for the tax break the donor will receive. To ensure he doesn’t scam the system with an inflated value, this type of appraisal uses a market data approach that includes prices of “comparable examples” or sales of the artist’s work in recent years. The appraisal also incorporates any pertinent information on the state of the art market at the time of the gift with regard to the artist, as well as a biography and testament to her relevance in relation to a particular art movement or period. In other words, the appraiser must prove the fair market economic value of the work as it relates to its cultural value in order for the IRS to accept the designated price.

These values are not static; they change with inflation, the ebb and flow of the market, and trends in the art world, which is why private collections are reassessed on a regular basis for insurance purposes – another moment at which monetary value is assigned to art. Perhaps surprisingly, most art museums do not insure their full collections, which would be prohibitively expensive. Instead, individual artworks are insured only when they leave their permanent homes, usually as part of an exhibition or occasionally for conservation. At that time, the works are re-appraised, their value once again determined to guarantee full coverage in the case of damage or loss, such as theft. If either occurs at home where the work is uninsured, the piece will be appraised retroactively for what it would have been worth at the time of the incident.

In 2004, Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893) and Madonna (1894) were stolen from the Munch Museum in Oslo. After the heist, their combined value was set at $121 million. The works were later recovered, but without an art appraisal, insurers would have been unable to determine how much to compensate the museum. By establishing the market value of an artwork, an organization can give itself options should the unforeseen occur. The money recovered from insurers will generally be put towards repairing any damages incurred, or if that’s not possible, acquiring another art piece. Both measures clearly benefit the collection and the public trust.

Exhibition History and Provenance

Museums don’t just establish the price of the art in their collections, they also help determine the value of works they never even consider buying. An artwork’s economic value is affected by its exhibition history and provenance—where it was shown, where it was written about, and by whom it was owned—so it’s in a collector’s best interest that it be seen in the right company.

When it comes to exhibitions, it is standard practice for museum curators to approach collectors about lending artworks for inclusion in upcoming shows featuring the artist’s work or area of influence. The wall text adjacent to an art piece in an exhibition can be a useful tool for illuminating the subtle presence of the art market in the room. Next time you attend a museum show, pay close attention to the last line of this catalogue description. If the provenance states, “From the collection of…” you can smile and nod with the knowledge that the lender has just added a feather to the artwork’s proverbial cap, an advantageous qualifier should he ever wish to sell it.

The cultural seal of approval that an art institution can issue extends beyond the objects within its own collection and those lent for exhibitions. It can affect an artist’s entire oeuvre, increasing the value of un-exhibited privately owned works as well as new ones offered for sale. One gallerist promoted the work of Israeli artist Leora Laor to a client by informing him in a letter that the The Jewish Museum was considering the purchase of Laor’s photograph Borderland #1006. In this case, the gallerist felt that even interest on the part of a museum would be a factor in the collector’s decision. Similarly, a well-received exhibition about a particular period or style can cause a flurry of buyer activity in the retail sector, as happened with a 2006 traveling showcase of 19th-century Biedermeier fine art and furniture that was hailed in the New York Times as a “a harbinger of many things modern.”

An installation view of “Biedermeier: The Invention of Simplicity” at the Milwaukee Art Museum in 2006. Photo credit: Chris and/or Kevin

On occasion a museum may mount a show comprised solely of works owned or donated by one collector – a practice sometimes referred to as a “vanity exhibition.” If the collector is still living, the museum may enter into the preliminary stages of acquiring his collection or first right of refusal, wherein they show the work in exchange for donations of art or a cash gift. The collector/donor benefits by adding exhibition history and provenance to his artworks and glory to his legacy, while the museum in theory benefits by expanding its collection – although the artwork may or may not eventually end up there. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art came under fire for agreeing to a 2001 exhibition of works from trustee Eli Broad’s collection without procuring a contract ensuring that some pieces would be donated to the institution. LACMA never received any of the work—Broad decided to open his own museum—but prior to that he made a $60 million contribution for a contemporary art wing bearing his name.

The incident with Broad points to the complex relationship nearly all art museums have with deep-pocketed benefactors positioned behind the scenes as trustees, committee members, and influential donors. It’s difficult for their personal and financial interests not to get entangled with the institution and their collections, which is why museums must walk an ethical tightrope when it comes to public-private partnerships. While their presence ensures that the museum will always be indirectly tied to the marketplace, it also allows institutions a certain amount of autonomy from the limitations of government funding and it can even offer protection for works of art under threat. In the case of the DIA, for example, Emergency Manager Orr and the city’s creditors have largely shied away from the majority of the collection that was donated or acquired with private funds, lest donors and their heirs unleash a slew of lawsuits similar to the one recently filed (and later retracted) by two founders of the Dia Art Foundation in New York.

The Art in Art Appraisal

We’ve examined some of the ways market value and museums intersect, but who exactly is appraising all of this artwork? Is it a group of sticker-happy thieves who will sell world-class art like your Nana’s cheap china at a yard sale? Absolutely not. Art appraisers are also art appreciators. They have a discerning eye for the energy of the brush stroke, effect of light, complexity of composition, and artist’s intent. Most hold degrees in areas of art, history, and cultural studies, as well as economics and administration. The principal appraiser at the firm I work for is a contributing member of several Los Angeles-area art museums, an owner of a diverse collection of paintings and “tramp art,” and has consulted on several art books and catalogues. If you’ve ever watched Antiques Roadshow or History Detectives, you get a pretty good idea of the level of an art appraiser’s interest and knowledge in the work he or she evaluates. Even auction catalogues feature special spreads that include artist’s biographies and attest to the cultural relevance of particular works for sale.

Contrary to fears that dollar signs will devalue art’s intrinsic qualities, those of us who are in the business of knowing the most about its market value are devoted museum patrons, members, collectors, and even artists ourselves – as in my own case. We are deeply aware of what makes an art piece valuable in a cultural context and worthy of its place in a museum.

But what about the broader public? Could highly publicized, often astronomical market prices for significant artworks lead to a general sense that art is only as valuable as the dollars it can be exchanged for? There is reason to believe that the risk is low. Even as New York Times art critic Roberta Smith bemoaned the “new high-water mark”—$142,000,000.00!—set by the recent sale of Francis Bacon’s Three Studies of Lucian Freud, she pointed to a 1980 purchase by the Whitney Museum that made headlines at the time. The prestigious art institution bought an encaustic painting by Jasper Johns called Three Flags for an era-shocking $1 million. But no one talks about that when they see the work hanging in the museum today. It has weathered the once negative press resulting from its hefty purchase price remarkably well, becoming a popular icon of American 20th Century art.

Jasper Johns’ iconic work Three Flags (1958) was purchased by the Whitney Museum in 1980 for $1 million.

A recent survey of Detroit citizens suggests a similar public resilience to artwork valuation. Despite the high estimates that have been tossed around in the media, reportedly 78% of locals surveyed would prefer not to sell the DIA’s art to satisfy city creditors, despite the city’s dire economic straits. And in another interesting development, Detroit’s creditors have accused Christie’s of undervaluing DIA artworks, the appraised portion of which are preliminarily estimated at $452-866 million. Their disappointment in the early assessment reveals how a prudent appraisal is less about giving the “kleptocrats” what they want than determining a value that accurately reflects the arts’ cultural and historical position within a market.

So if monetary value need not displace aesthetic or cultural value, it seems to me that we want art to be prized in the marketplace – which also means being priced. Though it may seem tasteless to talk cold hard cash when it comes to our cultural heritage, monetary worth is one of the most direct ways in which our culture speaks about things it truly values. Rather than trying to avoid pricing art all together—nearly impossible in a late-capitalist society—it might be more productive to think like an art appraiser and ask why the work is worth what it is at this particular moment in time. Examining the reasons reveals a lot about our cultural interests, state of the economy, and wealth distribution. The ability of an art collection to capture the attention of an American city’s creditors is disconcerting as a sign of culture’s vulnerability when our urban centers are poorly managed, but for a field constantly beset with worries of its declining relevance and difficulty reaching a broader audience, the public’s subsequent resistance in letting that artwork go should be something for arts lovers to celebrate – a sure sign that people really do care after all. In the opinion of this art appraisal associate, a world in which the price of certain artworks is ludicrously high is far less scary than a world in which no one is willing to put a price on art at all.