For a 75% shorter read than what you’re about to experience below, try Studio Thinking: the condensed version.

At the turn of the millennium, arts education found itself increasingly under the axe in a school system beleaguered by budget cuts, low grades and poor test scores. Arts advocates and educators were scrambling to prove the worth of the arts as a means of boosting those test scores and grades in academic subjects deemed “more important,” like math and reading. Motivated by claims of evidence supporting this case, Project Zero researchers Lois Hetland and Ellen Winner conducted a meta-analysis of related research studies dating back to the 1950s to determine if there was in fact a direct correlation. They found no evidence to support the notion that studying the arts caused students’ standardized test scores or academic grades to improve. Arts advocates reeled at this disclosure, which provoked no small amount of controversy in arts education circles. Nevertheless, Hetland and Winner believed that by taking a different approach to the research—one based on the intrinsic value of teaching art rather than its instrumental effect on other subjects—they would be able to make a stronger case for the importance of studying art. They thus set out to determine the “real benefits” of a visual arts studio education. The result was the first edition of Studio Thinking: The Real Benefits of Visual Arts Education, authored in 2007 by Hetland, Winner, Shirley Veenema, and Kimberly M. Sheridan.

Studio Thinking exhaustively presents the researchers’ careful observations and analysis of 28 visual art projects taught in five high school level studio art classrooms. Their findings suggest that students not only learn “dispositions” specific to visual art, but also six general “habits of mind” that are potentially useful in other subjects. A second edition published in 2013, Studio Thinking 2, features a new addition to the core Studio Structures of Learning, further explanation and examples of habits of mind, and new information on the application of the authors’ research since the book’s first publication.

Summary

Studio Thinking and its update present what the authors identify as the “real curriculum” of a visual art studio education. The authors focused on the visual arts to establish parameters for the study, but hoped that others would look more closely at other arts disciplines. At the time the initial research for Studio Thinking was conducted, there was no other arts-related research that examined the day-to-day teachings of studio art, so the authors developed a methodology based on traditions established by three pioneering non-arts classroom studies: Magdalene Lambert’s Teaching Problems and The Problems of Teaching; James W. Stigler & James Heibert’s The Teaching Gap; and Harold Stevenson’s The Learning Gap.

To observe studio instruction in practice, Hetland and Winner worked with five visual arts teachers at two Boston area high schools with “exemplary” arts programs, the public Boston Arts Academy and the private Walnut Hill School for the Arts. They chose the former for its student demographics, which mirrored those of the Boston area. The Walnut Hill student body, by contrast, was mostly middle and upper-middle class, with a diverse mix of local and international urban and suburban students, and a high concentration of Koreans. At both high schools, students were admitted by portfolio review and/or admissions assignments and interviews. They spent a minimum of three hours a day working on their art under the guidance of their teachers, all of whom were also practicing artists with Master’s degrees in art or art education.

The setting of the study is the studio class environment, which, according to the authors, differs from a “traditional” classroom setting in a number of ways. Traditional classrooms arrange desks in rows facing the front of the class. The teacher often lectures or gives a presentation, and sits at his/her desk while students work on tests or other in-class assignments. In an art studio, by contrast, easels, horse-stools, and various seating apparatus are typically arranged in a loose circle. In the center of the room the teacher lectures, demonstrates, or sets up a still-life model. When not giving a presentation, the teacher roams the studio space executing tasks or visiting students at work. Special lighting and music may also be employed in the studio class to promote an active and focused atmosphere.

Over the course of the yearlong study, Hetland, Winner et al. observed the instruction of 28 art projects. Using an admittedly subjective approach, they worked to incorporate evidence-based methods in the study as much as possible. By videotaping the classes, they were able to compare their direct observations with documentation and more thoroughly analyze student-teacher interactions. They requested post-class written reflections from teachers, conducted interviews with students, and examined samples of the student’s artwork for learning patterns. A code system was created based on their initial analysis, which took into account teacher’s intentions as stated in their interviews and calculated how often specific habits and skills were taught. The code was further refined with the assistance of consulting field specialists and distilled into categories that described what the researchers had observed being taught. Through this rigorous process, they were able to identify four “Studio Structures of Learning” and eight “Studio Habits of Mind.”

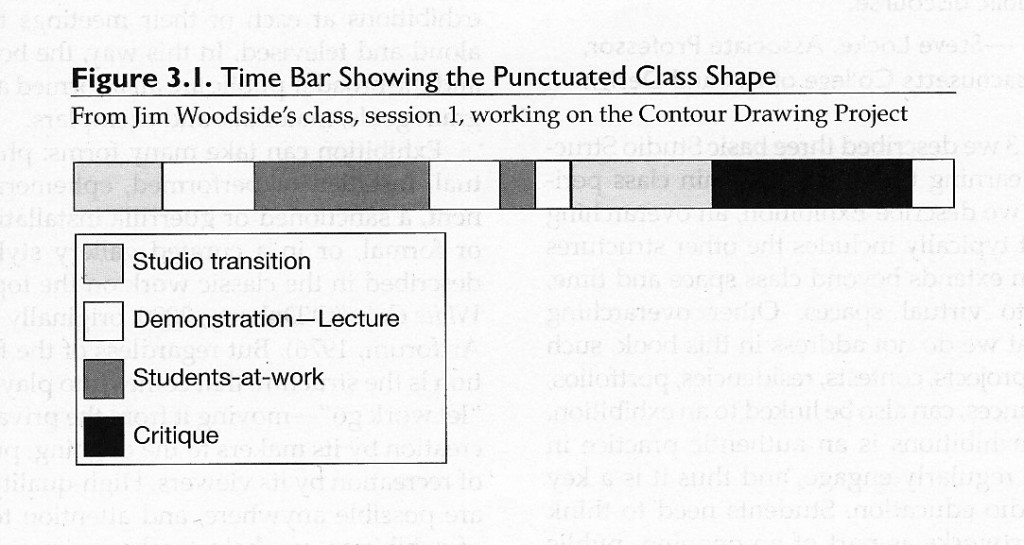

According to the authors, the Studio Structures for Learning are four modes of instruction germane to the studio classroom. Initially observed in each teacher’s class were three structural elements: Demonstration-Lecture; Students-at-Work; and Critique. Each studio class features a combination of these activities. In Studio Thinking 2, Hetland, Winner et al. introduce a fourth culminating structure called Exhibition. It is described as an “overarching” structure that encompasses the original three. The authors also identify a fifth sub-element called Transitions, which is the time spent transitioning between all other structures.

An illustration of how four Studio Structures are integrated into Walnut Hill teacher Jim Woodside’s studio class. The authors call this studio time organization a Punctuated Class whereby the structures are layered with shorter intervals between them.

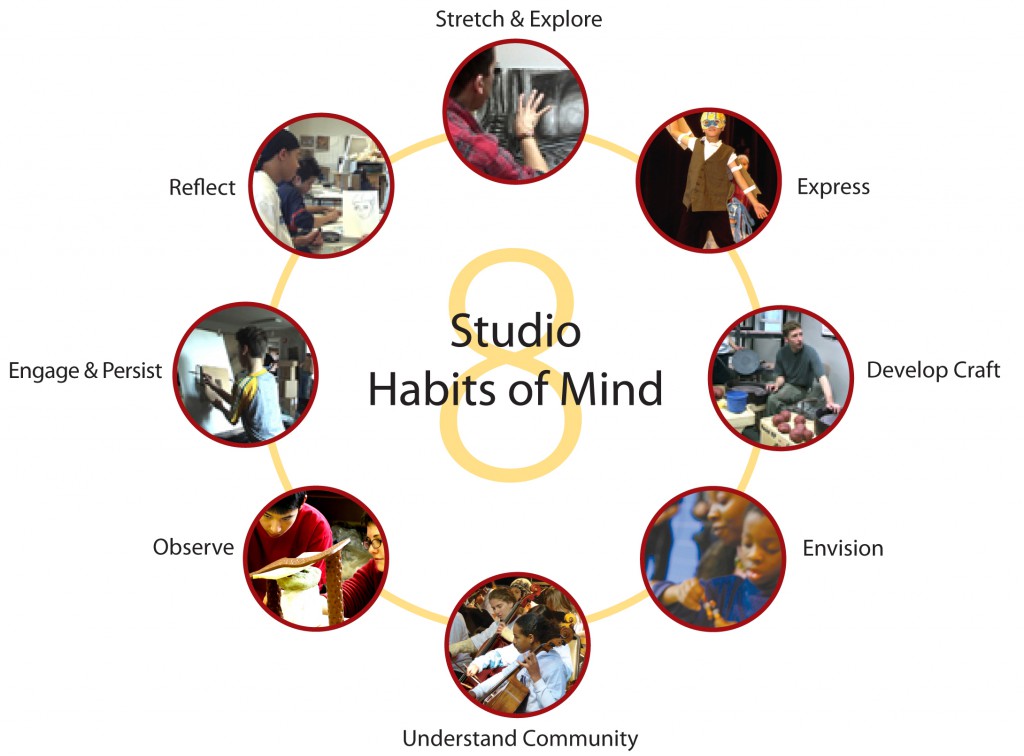

These Studio Structures create a supportive atmosphere for learning eight “Studio Habits of Mind” (referred to in the text by the somewhat unwieldy acronym SHoM): Develop Craft, Engage and Persist, Understand Art Worlds, Stretch and Explore, Envision, Express, Reflect, and Observe. The authors assert that these SHoM are what the studio arts “actually” teach. Each is considered a “disposition”—a term and theory borrowed from the work of Project Zero co-founder David Perkins and his colleagues—or way of thinking that includes specific core skills, an inclination to use those skills, and an alertness to opportunities to put them to use. Not all eight habits of mind are not necessarily present within each studio project, but usually several are learned within a successful course. The authors found that the habits are taught in a non-hierarchical manner, each no more important than the rest, and a class may consist of several habits taught in “clusters” and/or interwoven into the Studio Structures.

Each structure emphasizes the studio habits in different ways. For example, when Walnut Hill teacher Jason Green gave a presentation on clay assembly, the researchers observed four SHoM embedded in the Demonstration-Lecture segment of his class. As he manipulated the clay and spoke, the students “learn[ed] to observe as they look[ed] carefully at ceramics; they learn[ed] to envision as they plan[ned] their designs; they learn[ed] to express as they think about conveying some kind of idea or feeling in their set; and all the while they [were] learning to acquire technical skills required for expertise in ceramics.” Put in the authors’ terminology, the teacher “used a ‘cluster’ of Observe-Express-Envision-Develop Craft: Technique.”

The Students-at-Work structure allows students to spend in-class time working on an assignment, while keeping the classroom focused on art-making goals. Teachers are able to give individual attention and address the specific needs of each student, creating a tailored approach to learning studio habits when students require help. While a cluster of SHoM are embedded in the art project, the teacher draws each student’s individual habit needs into the foreground as he circulates the room to offer one-on-one guidance. For example, a student may be encouraged to “Envision” what another color would do for a painting, or “Persist” in pulling the final composition together.

In the context of the Critique structure, the period when students and teacher collectively analyze individual artworks, the students integrate SHoM through a process of inquiry, observation, and discussion. This structure allows them to make connections with habits different from those that may have been taught in other stages of the class. During a critique, the teacher may compare a student’s unique style to a particular artistic movement unfamiliar to the class (Understand Art Worlds). Another student may be asked to explain why she made a particular artistic decision (Reflect) and how the work would differ if she had done it another way (Envision and Express).

New to the second edition of Studio Thinking is the fourth structure, Exhibition, which the authors claim incorporates all eight SHoM. Through the staging and presentation of the artwork produced within the Studio Structures, students learn different but supportive skills that provide a broader context for understanding the purpose of art, and for deepening their comprehension of the studio habits.

The combination of Studio Structures and SHoM is what Hetland, Winner et al. call the “Studio Thinking Framework.” An interesting outcome of the original study, described in the second edition, has been its application as a method of self-assessment for both teachers and students. Rather than focusing solely on skill development, such as drawing techniques, instructors may evaluate their own teaching weaknesses and strengths through the lens of the framework, or set goals to improve certain dispositions in their students by altering their teaching approach. The authors also report instances where students themselves have used the framework to assess and improve their skills and dispositions.

Other Applications of the Studio Thinking Framework

Hetland, Winner et al. suggest that the Studio Thinking Framework can also be useful in non-classroom settings, such as teacher education programs, museum and gallery education, new technology research, and even policymaking. The authors suggest using the framework to inform new teachers of the “purpose and rigor” of arts education and to improve museum- and gallery-offered courses. They also present ideas for adapting the framework to non-arts subjects, and attest to witnessing its use in a variety of classroom environments:

Teachers have reported to us that the Studio Habits of Mind are broad enough to offer guidance for curriculum and teaching in their disciplines, and the Studio Structures for learning foster classroom cultures of thinking and learning across disciplines by modeling how to organize classroom time and interactions around personalized and collaborative projects.

According to the authors, non-arts subjects can easily make use of the Studio Thinking Framework by dedicating most classroom time to the Students-at-Work structure. By using a studio, laboratory, or workshop model, teachers can personalize the classroom setting, provide instruction across a wide range of skill levels, and more effectively guide students in their dispositional learning.

Hetland and Winner, with the help of Lynn Goldsmith of Education Development Center, are currently using the framework as a guide to conduct a study that examines the transference of studio thinking – i.e. the degree to which students’ engagement with the SHoM leads to their using similar dispositions when engaging with subjects such as math and reading. At the time of Studio Thinking 2’s publication, the authors were only able to cite one instance of potential direct transference of a SHoM (Envision) to a non-arts discipline (geometry). Preliminary findings from comparing the performance of arts majors, theater students, and after-school squash players on spatial geometry problems developed from standardized tests indicated that the art majors performed better initially and also gained more on the test than the other two groups. The authors caution, however, that the experiment does not conclusively demonstrate transfer because they were unable to assign students randomly to the three groups to create a “level playing field.”

Analysis

According to the authors, the Studio Thinking Framework is “a set of lenses for observing and thinking about teaching and learning in the visual arts and beyond.” In Studio Thinking and its second edition, the authors succeed in presenting visual arts studio teaching as a flexible model that not only promotes art techniques and skills, but also critical observation and thinking habits that are applicable in many disciplines. The four Studio Structures and eight Studio Habits of Mind are easy to comprehend and have broad appeal. Together they provide a dispositional vocabulary that augments the skill-building aspects of an arts curriculum with an alertness to opportunities and inclination to use those skills beyond the classroom. With the Studio Thinking Framework, the authors have created a common language and working model that can be used by educators, administrators, and policymakers in discussing arts education. That enables advocates to speak more broadly about what is achieved through arts learning.

Indeed, the Studio Thinking Framework has been widely embraced since it was first introduced, with the original Studio Thinking making the New York Times bestseller list. On a national level, the authors have consulted on the development of Turnaround Arts Initiative, a project of the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities, which pairs several under-performing urban elementary schools with famous artists like Yo-Yo Ma and Chuck Close to provide enriching studio-style arts classes. At the state and local level, the new Common Core State Standards place an emphasis on the dispositional vocabulary invoked in Studio Thinking and are arguably supportive of the authors’ position that SHoM is the core of arts education. As part of a K-12 arts integration program in Alameda County, California, the framework has been implemented as a shared conceptual language across disciplines to communicate with teachers, administrators, advocates, and parents. Their students have been taught to use SHoM as a method of self-assessment and critique.

Despite this positive reception, Studio Thinking suffers from several limitations in its methodology and design that narrow the extent to which it truly “makes a case” for different forms of arts education. The authors acknowledge that the study’s reliance on ethnographic methods renders it inherently subjective. Another set of researchers might have identified a different set of habits, such as those outlined in Eric Booth’s “The Habits of Mind of Creative Engagement.” It is important to understand that Studio Thinking‘s descriptive and theoretical approach makes no attempt to “prove” anything about the benefits of arts education, but rather “make a case” for them.

Studio Thinking focuses on the visual arts at the expense of other arts disciplines, although the authors report a few positive findings and comparisons by other researchers and experts in the areas of dance, theater, and music. Notably, Boston Ballet’s Center for Dance Education conducted a two-year study to determine whether the habits were taught in dance and concluded that all eight were present in their dance studio classrooms. Matthew Hazelwood, former conductor of the National Youth Orchestra of Colombia, reported using SHoM as a way to enrich his orchestra class instruction, and theater teacher Evan Hastings is using the framework to help his students track and assess their own development. Nevertheless, more research is needed to determine how applicable the framework is across all arts disciplines.

Finally, the study was conducted in just two high schools in the Boston area, both of which cater to students who already have a strong interest in and aptitude for the arts. The visual art classes studied by Hetland, Winner et al. mimic a pre-professional studio teaching style commonly found in college-level and adult arts courses, which is unusual in most high and middle schools and practically non-existent at the elementary school level. If the “real benefits” of arts education are found only in a college-style course, the research may have little to say about the art classes more common to secondary and primary settings, taught as they are in most cases by teachers less skilled or credentialed than those the authors observed. Would the eight studio habits have been as evident if classes serving students new to the visual arts, or younger students, or special-needs students, had been a part of the study? And would those same students learn the SHoM as readily as the arts-inclined students in a studio-structured environment?

Given these methodological limitations, the authors’ use of the framework in transfer studies, their promotion of it as a tool of advocacy, and arts advocates’ quick adoption of it, all seem a bit premature. While Studio Thinking has certainly added to the arts education conversation, the findings arguably appear only to scratch the surface of the benefits of teaching art. Rather than rushing to test transference and apply the framework across disciplines, it would be more prudent and helpful to conduct research that compares the differences between teaching arts and non-arts subjects to both arts-interested and uninterested students from the perspective of studio habits of the mind. Doing so might more accurately pinpoint the benefits of arts education relative to other subjects and students, and go much further in supporting the authors’ claim that the arts teach “a remarkable array of mental habits not emphasized elsewhere in school.”

Implications

Studio Thinking‘s reception to date, and in particular the alignment of the Studio Thinking Framework with the President’s Committee’s agenda and the Common Core State Standards movement, suggest that the authors’ findings will have some long-term influence on the way educators, advocates, and policymakers think about studio arts and education as a whole. In doing so, will it make an intrinsic case for the value of teaching the arts?

The eight Studio Habits of the Mind as implemented by Alameda County “Art is Education” program. Note: Understand Art Worlds has been altered to Understand Communities.

On the one hand, these developments are encouraging in a country where arts education has been increasingly marginalized over the last couple decades. The success of these early programs will have a hand in determining whether the Studio Thinking Framework will continue to have influence and application. If the results are favorable, perhaps more studio-style arts classes will be incorporated into students’ everyday curriculum in the interest of promoting a studio-centric version of increasingly popular habits-of-the-mind learning. Studio Thinking openly advocates for incorporating studio teaching methodology into these other classroom formats and, in this way, the authors offer a way of valuing arts education that could potentially encourage a demand for it.

But this also implies that Studio Thinking makes a case for studio format arts education as the only area where these particular skills and habits can be learned, which it doesn’t. The authors make a pointed effort to illustrate how SHoM can be applied to non-arts subject areas. If students can get the same benefits from conducting a chemistry experiment or building a physical model based on mathematical theory as long as there is an emphasis on habits like Envision, are we once more back to the drawing board in trying to articulate why arts education is important?

The decision to focus on the results of the method of teaching should concern arts advocates. It suggests an easy leap for policymakers to say, “Thanks for showing us how to better structure curriculum and classes for the other still ‘more important’ subjects. So now we really don’t need the arts.” As it is, the authors’ ongoing research into using the Studio Thinking Framework as “the foundation for more precisely targeted and plausible transfer studies” hews closely to the instrumental language of looking for causal relationships between the arts and other academic disciplines. If the studio structures and habits are indeed the “the real benefits of visual arts education,” then using the framework to once again test for improved performance in other subject areas is more than a little ironic.

Does Studio Thinking promote a space in society where teaching the arts is valued for its own sake and not a means to an end? In one sense it does isolate how studio learning encourages the development of important critical skills necessary to produce creative, engaged individuals. However, as the emergent Studio Thinking movement focuses more on expanding and generalizing what is learned in studio classes beyond the studio, a clear distinction between the effects of the art and the effects of the teaching will become increasingly important.

Additional Reading:

- Ellen Winner and Lois Hetland, Art for Our Sake

- Peggy Burchenal, Abigail Housen, Kate Rawlinson, and Philip Yenawine, Why Do We Teach Arts in the Schools?

- Ellen Winner and Lois Hetland, Continuing the Dialogue

- John Broomall, Is This The Book That Will Change Arts Education?

- Lois Hetland, Why do we need the Studio Thinking Framework, anyway?

- Ellen Winner, Lois Hetland, Shirley Veenema, Kimberly M. Sheridan, et al., Studio thinking: How visual arts teaching can promote disciplined habits of mind