Image by Giulia Forsythe via Flickr

The field of education is swimming in acronyms (care to forecast what a new AYP system will look like once CCSS fully replaces NCLB?) but a new one, MOOC, is causing a stir. MOOC, which as a New York Times columnist dramatically emphasizes, “aptly rhymes with nuke,” is shorthand for Massive Open Online Course.

In the simplest of terms, a MOOC is an online mechanism for teaching and learning that (metaphorically) blows the walls off the traditional classroom, and the gates off the traditional campus. In a MOOC, the instructor still stands at “the front of the room” and delivers content, but the audience has expanded to hundreds of thousands of people. And most of those people haven’t had to go through an arduous admissions process or, better yet, pay a nickel to get in the (virtual) door.

It’s important to pause here and stress what a MOOC is not. The online course you took for credit three years ago? Not open to everyone and probably didn’t have enrollment surpassing 100; not a MOOC. The free webinar your local funder hosted about a new grant program? While informative, it was not a sequential, structured course offering, therefore not a MOOC. The free course material, including videotaped lectures, course notes and reading lists you happily lap up on MIT Open CourseWare or Open Yale Courses? The content may be fascinating, but as it is posted in bulk without a registration process, live instructor, or formal assessment systems, it is also not a MOOC.

Online learning models have existed since the dawn of the Internet, and private universities have experimented with posting free content for years. The concept of a MOOC, however, is fairly new. One of its more obvious precursors, Khan Academy, is only about seven years old. Khan Academy began when its founder, Salman Khan, posted short, low-tech videos on YouTube to help his nieces and nephews learn math thousands of miles away. Today it boasts more than four thousand short videos and exercises on everything from arithmetic to physics, and interactive learning dashboards that help students pick their next lessons. According to lead developer Ben Kamens, it has about fifteen million registered users.

Khan Academy gained significant attention in 2010 with large grants from Google and The Gates Foundation. Around the same time, higher education began experimenting with putting content online in new ways. In 2011, Stanford professor and artificial intelligence guru Sebastian Thrun offered his popular Introduction to Artificial Intelligence course to anyone with an Internet connection and ten hours a week to spare. A year later he founded Udacity, one of the two most well known MOOC providers. The other, Coursera, was launched by Thrun’s Stanford colleagues the same year. Meanwhile, Harvard and MIT teamed up to launch EdX. Berkeley, Princeton, Columbia, and others jumped on the MOOC bandwagon, adding courses to the Udacity, Coursera, and EdX rosters. Suddenly MOOCs were all the rage. Little more than a year after the silly-sounded acronym was coined, the California senate passed a bill requiring universities in the state to offer and provide credit for MOOC alternatives to “oversubscribed” classes – i.e. courses that students needed to graduate, but were shut out of as a result of California’s pernicious budget issues.

The diversity of MOOC offerings has expanded as rapidly as their number. The majority of early MOOCs (and remember, by “early” I mean they launched waaaay back in 2011) tended toward math, engineering, and computer science courses with multiple-choice exams that could easily be processed by computer. As of this writing, however, Udacity has added “design” as a new course category. Coursera, meanwhile, boasts courses on everything from poetry to comic books to public speaking. Coursera has also partnered with alternative education sites, including the Museum of Modern Art, which recently offered a MOOC on museum teaching strategies for classroom educators, and the American Museum of Natural History.

Now to those of you who, like me, have found yourselves swept up in reminiscences of the reading list for an awesome philosophy course you took in college, a MOOC sounds the best thing since your dad gave you a set of “great lectures on world history” CDs for your birthday (‘fess up: you loved them). But in their short-but-swift lifespans, MOOCs have inspired their fair share of controversies. Some are small-scale and amusing hiccups, like the case of the failed MOOC about how to teach a MOOC. Others, however, raise deeper questions about pedagogy and quality control. While “massive” numbers of people sign up for MOOCs, very few – according to one study, less than 7 percent – stick around to earn course credit or a formal certificate of completion. How do you prevent them from cheating—and how do you determine whether they are learning anything? A professor at the University of California, Irvine abruptly quit teaching a MOOC on microeconomics, citing difficulties in getting his thousands of students to read required material. Meanwhile, philosophy professors at San Jose State University formally protested the school’s plans to partner with EdX and Udacity, arguing MOOCs, “designed by elite universities and widely licensed by others, would compromise the quality of education, stifle diverse viewpoints and lead to the dismantling of public universities.” San Jose State went ahead with its plans and suffered another setback a few months later, when more than half of the students signed up for the first round of MOOCs failed their final exams. The university has since put its MOOC experiment on hold, though early rumblings indicate it may return, with some changes, next year.

Despite these difficulties, there are enough success stories that interest in MOOCs shows no sign of waning. MOOCs may well be on the verge of disrupting higher education in the United States. If they do, they will have a revolutionary impact on K-12 public education – and, by extension, arts education. At first glance, MOOCs don’t appear particularly relevant to the arts. While a handful of arts-focused institutions have jumped on the bandwagon early (offering courses like “Creating Site-Specific Dance and Performance Works”), so much of best practice in arts education relies on hands-on experience that it’s difficult to grasp at first how online platforms could impact it. However, arts educators working with public school systems on a frequent basis need to pay attention for three reasons:

- Online learning may soon move to the top of any district official’s priority list. An effective K-12 system must provide a clear pathway to higher education, and our new Common Core State Standards put an unprecedented emphasis on college and career readiness. If our notion of how college is structured changes, traditional K-12 classrooms will shift accordingly.

- If it does, those in the arts and humanities fields will have some catching up to do. Unsurprisingly given MOOCs’ origins, people in science and technology fields seem more favorably abuzz about MOOCs than those in the arts and humanities. While pedagogical concerns are valid, insisting our fields cannot be translated to a MOOC-like learning environment may set up an unhelpful contrast between artistic and scientific disciplines. Not long ago the University of Florida entertained a controversial “differential tuition” proposal that would have involved charging students less to enroll in science, technology and engineering courses than arts and humanities courses. The university’s rationale was to provide students added incentive to enter fields it felt spur economic development. While the debate never got into MOOCs specifically, it may foreshadow cost/benefit analyses that will only get more pointed if even a handful of MOOCs succeed. And speaking of cost/benefit analyses…

- If MOOCs take off, they will turn the economics of education upside down. In their current structure – large, easily accessible, and most importantly, free – MOOCs may be to colleges and universities what Napster was to the music industry. MIT’s Michael Cusumano, pointing to the decline of newspapers, magazines, and the book publishing industry, cautions that price is an important signal of value, and that “’free’ sends a signal to the world that what you are offering has little value and may not be worth paying for.” He writes, “Stanford, MIT, Harvard et al, have already opened a kind of ‘Pandora’s box,’ and there may be no easy way to go back and charge students even a moderately high tuition rate for open online courses.” With the cost of higher education ballooning out of control, the idea that MOOCs signal it “isn’t worth paying for” may strike some as an overdue but welcome reality check. However, with Harvard University recently issuing a call to its alumni to serve as volunteer teaching assistants for the MOOC version of a popular philosophy course, one can’t help but wonder if a new precedent is being set for the teaching profession. Is it possible that in the not-so-distant future, a handful of academic hotshots fresh off their TEDTalks will be paid handsomely, while their discussion groups are farmed out to unpaid interns or retirees?

Taking these three points together and thinking about the implications for arts education, the issue of cost immediately stands out. While cheaper isn’t always better, it is more tempting, particularly to elected officials and the public employees who work for them. A few months ago the Georgia Institute of Technology announced it would offer a new, virtual master’s program at one-sixth the price of its traditional master’s degree. If this learning paradigm becomes common practice in higher education, K-12 will try to follow suit. Working with a school to include and integrate the arts, though, particularly through a shared delivery model, takes a lot of time and money. Arts educators will therefore need to be prepared to articulate how their work with students and teachers can complement and enhance the broad financial and pedagogical shifts that MOOCs portend.

That means starting to think now about how arts education will translate to a different platform. A few years ago, Thomas Friedman argued that any jobs that can be outsourced, will be outsourced; by the same token, any knowledge and skills that can be taught online will be taught online. Certain components of arts education are likely to transfer well: basic vocabulary, the elements of visual art, how to read music. The questions that remain are a) which components can’t be included, and b) which of those are most relevant and engaging to students on their own terms. A recent report commissioned by The Wallace Foundation finds increasing numbers of students using online tools and digital technology to pursue “interest-driven arts learning,” a “form of participation where youths research and learn about their creative passions and hobbies, connecting them to peers with the same interests who may extend beyond their immediate social circle.” In doing so, students appear to be gaining the same skills they would otherwise acquire in K-12 learning settings. The report also notes a contrast between the digital tools young people use when they make art on their own and the traditional materials and disciplines they encounter in schools. Does this mean that traditional artistic disciplines will become obsolete in classrooms? No, but it may mean that they are used explicitly to reinforce skills like precision and attention to detail that students explore outside of the classroom first, and then can later apply directly to their work in Sketchbook Pro.

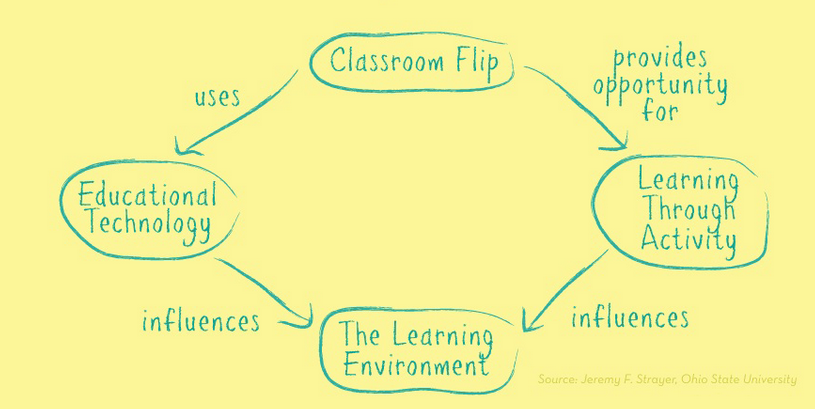

This idea that students use in-class time to practice, refine and experiment with basic skills they learn online describes a “flipped classroom,” and also represents the most optimistic scenario for MOOCs in the long run. In a flipped classroom, the traditional roles of classroom time and homework are reversed. Rather than learn a concept in the classroom and then apply it at home via worksheets, students acquire content online via a pre-taped lecture or Khan-Academy-like lessons. Then they come to class to discuss and experiment.

Infographic from Knewton

In this model, teachers are less content experts and more partners in learning. TED Prize winner Sugata Mitra took this idea further with his vision of a “School in the Cloud” in which learning is entirely self-directed and a network of experts and educators (many retired, it’s worth noting) support children across the world. If MOOCs find their footing in education, they could serve as a “great equalizer” of educational opportunity. Beginning in the 1970s, public television via Children’s Television Workshop (aka Sesame Street) was developed specifically to reduce disparities in kindergarten readiness between high- and low-income toddlers. By most measures, it succeeded. If online learning, via some version of MOOCs, were designed for children with similar pedagogical rigor, classroom time could free up significantly. Cross-disciplinary applications, project-based learning, partnerships with cultural and community arts providers… these could become the core of what happens in all schools.

That’s the optimistic scenario. The pessimistic scenario reserves everything I’ve described above for the wealthy. In the pessimistic scenario, second-tier and community colleges are no longer economically viable, leaving students who cannot afford to attend bricks-and-mortar colleges to navigate through a maze of MOOCs. Those with the innate motivation and inquisitiveness to create a “school in the cloud” do so; the rest do not. ”Public” education shifts to an online platform. Students in wealthy districts with active PTAs and education foundations have the means to keep their bricks and mortar classrooms as spaces of inquiry and experimentation. The rest supply their students with iPads (as some large, urban districts are already doing) but not much else.

I’m an optimist by nature, but avoiding the latter scenario won’t be easy. Recent research out of Stanford points to a widening gap between rich and middle/lower income families’ abilities to invest in their children: to provide tutors, after-school dance classes, and opportunities to travel and explore. As our Secretary of Education put it while summarizing national data on arts in schools, “the arts opportunity gap is widest for children in high-poverty schools.” If MOOCs and online learning take off, it will be much easier for arts education providers to adapt within schools where they have existing relationships – and which are probably wealthier — than to start from scratch elsewhere. For MOOCs to “level the playing field” rather than widen the gap, we will need to make basic digital infrastructure available to all students and target online learning efforts toward vulnerable populations. Sesame Street did it with toddlers decades ago using a public broadcasting forum, but unfortunately the Internet doesn’t yet have such an equivalent. The “digital divide,” meanwhile, is persistent; while broadband access has improved for most Americans in the last few years, many schools continue to lag far behind.

MOOCs are extremely young, and for all their hype, may flame out as quickly as they rose to prominence. We are prone to misreading the impact technology will have on our lives. When televisions first became ubiquitous in American households, those in the Instructional TV movement opined that televisions (or Big Bird?) might replace teachers. They were, obviously, wrong. Even if they are a passing fad, though, MOOCs can still teach us something about the pedagogical benefits and pitfalls of online learning, and about cracks in the economics of public education. Many arts educators cite “21st-century skills” and the demands of our “increasingly connected world” as an argument for teaching dance, drama, visual art and music in classrooms. As we consider the implications of increased connectivity for our students, we should take care to do the same for ourselves.