Last month, my post Creative Placemaking Has an Outcomes Problem generated a lot of discussion about creative placemaking and grantmaking strategy, much of it really great. If you haven’t had a chance, please check out these thoughtful and substantive responses by—just to name a few—Richard Layman, Niels Strandskov, Seth Beattie, Lance Olson, Andrew Taylor, Diane Ragsdale, Laura Zabel, and most recently, ArtPlace itself. I’m immensely grateful for the seriousness with which these and other readers have taken my critique, and their questions and suggestions for further reading have been tremendously illuminating.

Last month, my post Creative Placemaking Has an Outcomes Problem generated a lot of discussion about creative placemaking and grantmaking strategy, much of it really great. If you haven’t had a chance, please check out these thoughtful and substantive responses by—just to name a few—Richard Layman, Niels Strandskov, Seth Beattie, Lance Olson, Andrew Taylor, Diane Ragsdale, Laura Zabel, and most recently, ArtPlace itself. I’m immensely grateful for the seriousness with which these and other readers have taken my critique, and their questions and suggestions for further reading have been tremendously illuminating.

Now that the talk has subsided a bit, it’s a good opportunity to clarify and elaborate upon some of the subtler points that I was trying to make in that piece, which definitely left a bit of room for people to read in their own interpretations. So, just to be clear: despite the provocative title, I wasn’t trying to slam the practice of creative placemaking itself, nor call it into question as a focus area for policy and philanthropy in general. As I wrote in response to one of the comments on the original post, I believe strongly in the power of the arts to have a role in revitalizing communities, and I view the desire to direct resources toward bringing such efforts to life as a very positive impulse on the part of funders and policymakers. Furthermore, although I agree with the point made by John Shibley and others that the arts may not be the best way to foment economic development, no one said that cities and regions can only use one strategy. Economic development is a complex beast, and intuition and common sense would hold that there are most likely some specific situations in which the arts can have a real, irreplaceable, and catalytic impact.

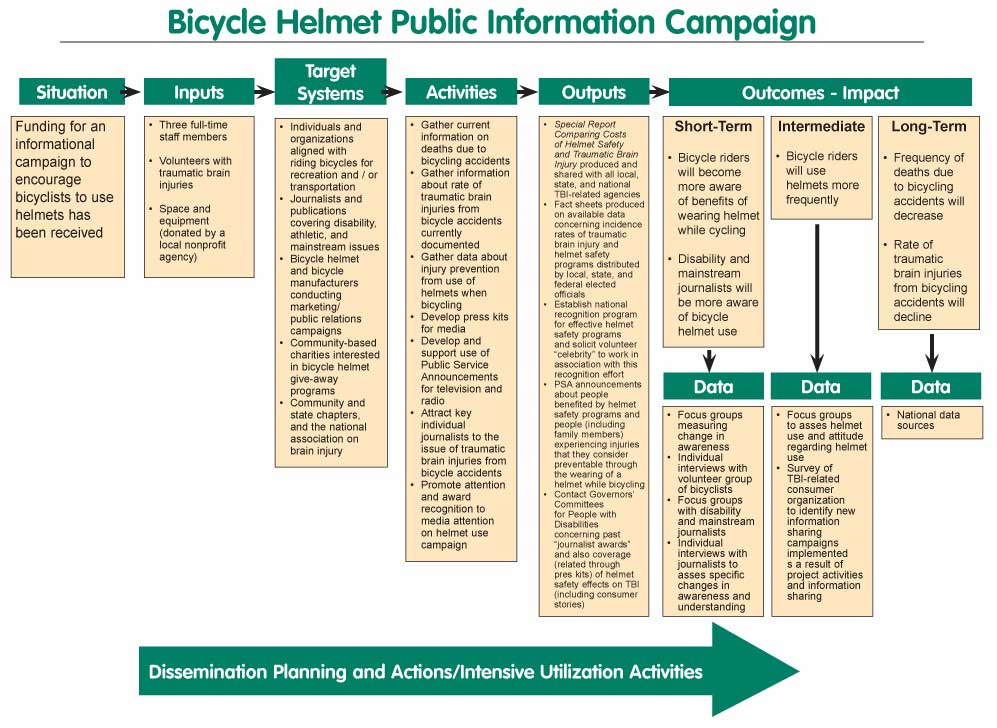

My critique is really about how we don’t have much information about what those situations are – nor about how infusions of philanthropic capital can make a difference in those situations. What’s more, I am not confident that the tools we’re currently developing, as useful as they may be for other purposes, will get us there on their own. My contention is that logic models and their conceptual cousins, theories of change, can be useful tools in filling this gap – by forcing us to articulate our assumptions about the way the world works, and by providing a framework that we can use to test those assumptions. The problem is that most of the logic models that I see aren’t worked out to the level of detail that I believe is necessary to gain really useful information about the dynamics of these complex processes. In my post, I provided a couple of examples of theories that, while surely far from perfect, at least attempt to recognize some of the numerous and interlocking assumptions embedded in grantmaking of the kind engaged in by today’s funders supporting creative placemaking.

It’s clear from some of the responses, however, that not everybody shares my optimism in the utility of logic models. Laura Zabel writes that she “hates” them for being too reductive. Diane Ragsdale, taking a cynical view, is worried that they may be misused by funders in order to make themselves seem smarter than they really are or blame grantees for failed strategies. ArtPlace’s response suggests that logic models raise the bar for research too high, and that because proving a causal connection between these investments and the change they produce (or don’t) is so difficult, we’re better off not trying. While I can sympathize with each of these critiques, I also think that they give logic models a bad rap. I feel that logic models are a tool of tremendous power whose potential is only beginning to be unlocked. It’s true that, just like philanthropy and policy, logic models can be done very badly. But that doesn’t mean there’s no gain for us in trying to do them well.

Before we get into all that, however, I’m guessing that some of you probably could use a refresher course on logic models and the terminology associated with them, which can be quite confusing. So let’s start with a little background on what this is all about.

What the Hell Is a Logic Model, Anyway?

Simply put, a logic model is a method of describing and visualizing a strategy. Logic models have their conceptual origin in the “logical framework approach” originally developed for USAID in 1969 by Leon J. Rosenberg of Fry Consultants. Their use was largely concentrated in the international aid arena until 1996, when United Way of America published a manual on program outcome measurement and encouraged its hundreds of local agencies and thousands of grantees to adopt logic models as a matter of course. Since then, large private funders such as the Kellogg and Hewlett Foundations have integrated logic models into their program design and execution, and the concept is commonly taught in graduate programs in public policy, urban planning, and beyond.

Even though logic models have achieved greater adoption over the past several decades, there is little standardization in the content, format, and level of ambition seen in professionally produced logic models for institutions large and small. Worse, everyone seems to want to come up with their own terms to describe features of the logic model, and as a result, you’ll notice a lot of variation in language as well. Below, I’ll do my best to isolate the elements that most of these efforts have in common.

Nearly all logic models contain the following fundamental elements. In combination, they describe a linear, causal pathway between programs or policy interventions and an aspirational end-state.

- Activities are actions or strategies undertaken by the organization that is the subject of the logic model. These activities usually take place in the context of ongoing programs, although they can also be one-time projects, special initiatives, or policies such as legislation or regulation.

- Outputs refer to observable indications that the above activities are being implemented correctly and as designed.

- Outcomes are the desired short-, medium-, or long-term results of successful program or policy implementation.

- Impacts (or Goals) represent the highest purpose of the program, policy, or agency that is the subject of the logic model. Sometimes you’ll find these lumped in with Outcomes.

Many realizations of logic models combine these essential elements with additional information that provides contextual background for this causal pathway. Several of these supplemental concepts are listed below in approximate order from most common to most obscure.

- Measures (or Indicators) for outputs, outcomes, and impacts are concrete, usually quantitative data points that shed light on the degree to which each result has been achieved.

- Inputs are resources available to the program or organization in accomplishing its goals.

- Assumptions are preconditions upon which the model rests. If one or more assumptions proves unsound, the integrity of the model may be threatened.

- Benchmarks extend the concept of measures to incorporate specific target goals (so, not just “# of petitions delivered to Congress” but “50,000 petitions delivered to Congress”).

- Target Population refers to the audience(s) for the activities listed in the logic model.

- Influential Factors are variables or circumstances that exist in the broader environment and could affect the performance of the strategy as designed (e.g., an upcoming election cycle whose outcome might change the underlying landscape in which the program operates).

What About Theories of Change?

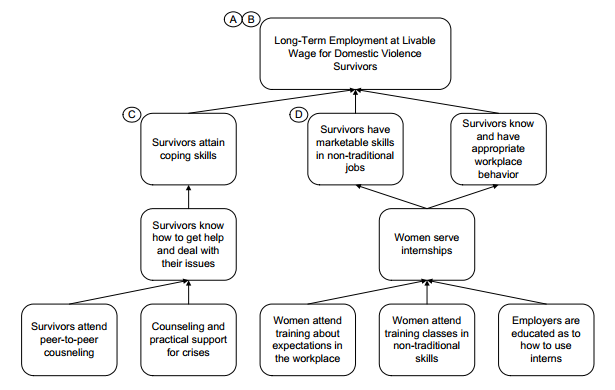

A frequently-employed alternative logic model approach strips out this latter set of contextual elements and instead aims to visualize the linear causal chain at a finer grain of detail. This version of a logic model is typically referred to as a theory of change (or, sometimes, a program theory). A well-executed theory of change diagram “unpacks” the processes and factors that lead to successful outcomes, exposing relationships between isolated variables that can then become the subject of research or evaluation.

Partial theory of change from Project SuperWomen case study (ActKnowledge/Aspen Institute Roundtable on Community Change)

Sometimes logic models and theories of change are presented as distinct concepts, while other times they really refer to the same thing. This is because logic models and theories of change evolved out of distinct communities of practice, but the philanthropic field has not always respected the distinction in the terminology it’s adopted to describe these tools. In my own practice I prefer to use theories of change, but for the sake of simplicity and readability, in the rest of this article I’m going to use the term “logic model” inclusively to refer to any diagram that clearly shows some combination of activities and outcomes, regardless of what other elements it may include or the visual approach it takes.

*

OK, now that we have our definitions in order, we can start talking about what makes logic models so awesome.

Awesome #1: Logic Models Describe What’s Already Going On in Your Head

So, here’s the thing: the core questions involved in creating any logic model—What am I trying to do? Why am I trying to do it? How will I know if I’ve succeeded or not?—represent the very essence of strategy. As a rabbi might say, “the rest is commentary.” If you have a strong sense of what the answers to these questions are, then you have a logic model in your head whether you realize it or not. All the diagram does is make it explicit.

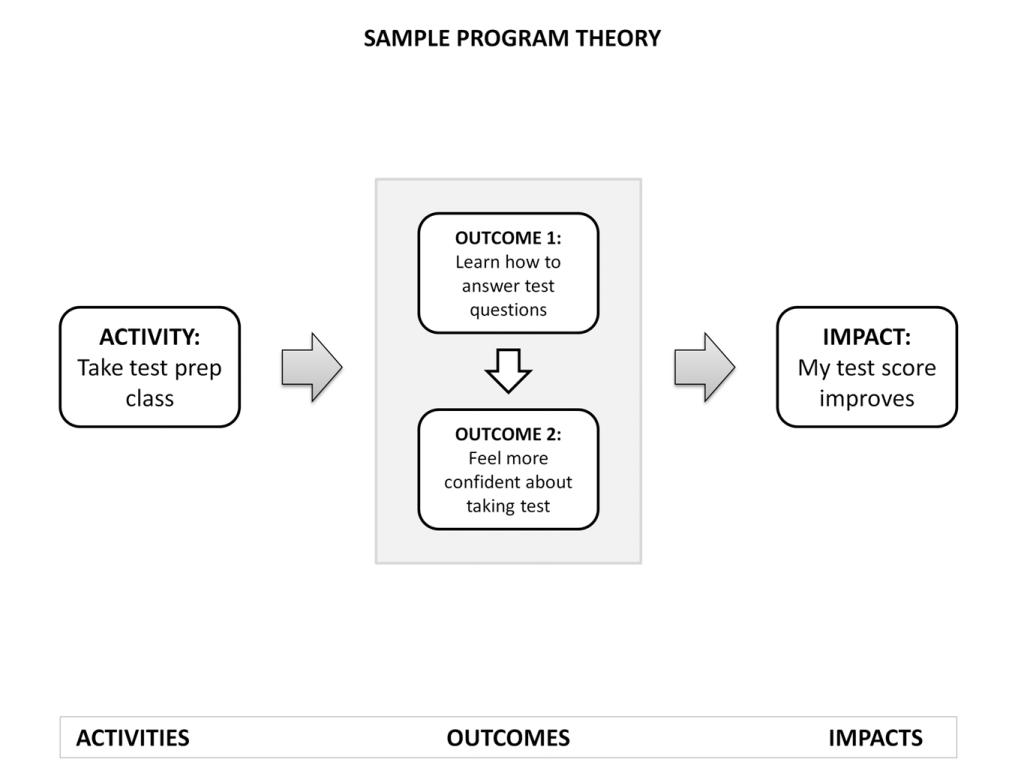

To illustrate this, we can look at a simple example. Let’s say I decide I’m done with this whole “arts” thing and I want to go to law school instead. I know, though, that in order to get into a good law school I need to get a good score on the LSAT. So, how can I make sure I get a good score? Intuitively, I decide that taking a test prep class is the way to go.

Why do I think taking a test prep class is a way to increase my score on the LSAT? Well, if my score isn’t as high as it could be, it’s probably due to some combination of two factors. First, I may not know the material well enough. So, if the class helps me to learn how to answer the test questions better, I’ll likely perform better on the test. Second, there may be a psychological factor as well. If I’m someone who gets nervous on tests, then my performance on them may suffer. The practice exams and deep engagement with the material that comes with a class could help me to get more comfortable with the idea of the LSAT and make it seem less intimidating, thus improving my performance.

Seems logical enough, right? And voila, it lends itself quite easily to a logic model:

The truth is that any decision you make, if it has any element of intentionality at all, can be diagrammed as a logic model. You might hate logic models with every fiber of your being and think they’re the stupidest thing ever created, but I’m telling you right now: if you believe in strategy, then you believe in logic models.

Awesome #2: Logic Models Are Incredibly Flexible

Now, there’s a difference between having a logic model in your head and having a good logic model in your head. The example above is simple, but it’s limited by that simplicity. It doesn’t explain why I might have decided to go to law school, or explore other ways that I could get into the school I want besides increasing my test score. In short, it’s pretty much just a straight-up mapping of a decision already made.

The best logic models don’t do that. Instead, they proceed with the end in mind (what is the goal we want to achieve?) and then methodically work backwards to understand what activities or strategies would be most appropriate to achieve that end. The ultimate outcome of this exercise may be a very different set of strategies than the ones you were originally contemplating or the programs you already have in place! Because of that, the logic model creation process can be great for opening up new ways of thinking about old problems or longstanding dreams, as well as clarifying what’s really important to you and/or your organization.

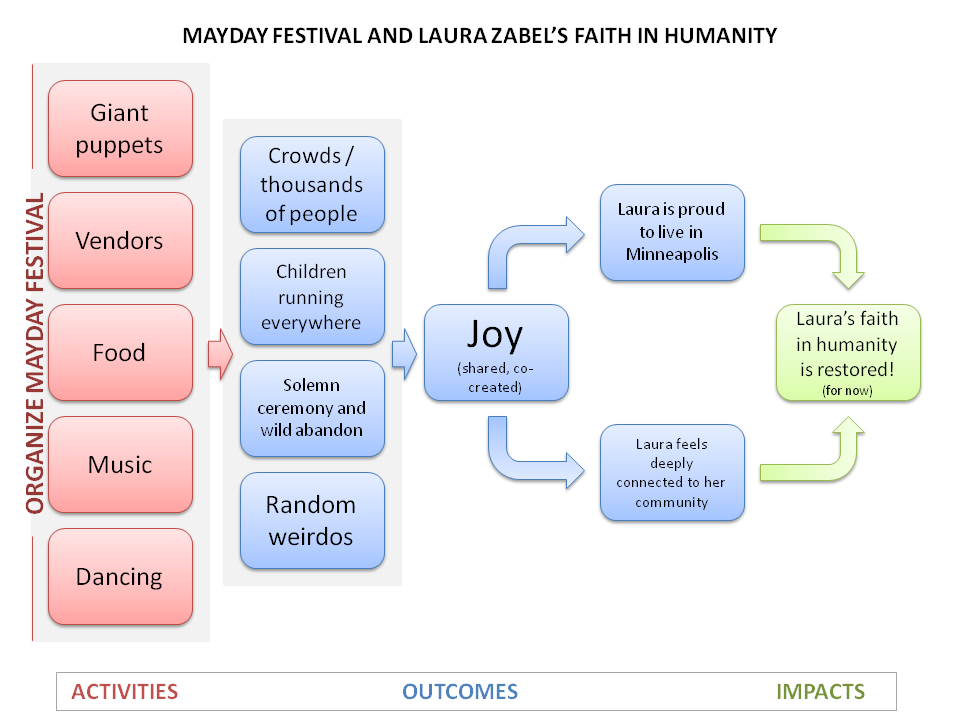

I mentioned earlier that not everyone is a fan of logic models. Here’s what Laura Zabel had to say about them in her post responding to mine:

I hate logic models. For me they are, somehow, simultaneously too reductive and too complex. Too simple, too linear for how I think the world works and too dry, too chart-y for how beautiful the world is. They make me irrationally grumpy.

Arlene Goldbard, in a 2010 essay, is similarly grumpy about logic models:

[R]equiring one of these charts as part of a grant proposal bears about as much real relationship to community organizations’ work as would asking each to weave a placemat…[T]he task of boiling the answers down to colored bars often wastes days, compressing most of the useful meaning out of the inquiry.

I can’t speak to Laura’s and Arlene’s experiences directly, but I know they are not uncommon. Unfortunately, logic models that are rife with imprecision, questionable assumptions, and inappropriate associations are more frustrating to work with than no logic model at all—and it’s not as easy as it looks to create logic models that are free of these flaws. Such problems are magnified when logic models are treated as edicts sent down from on high rather than the learning, living documents that they are intended to be.

In her post, Laura presents an alternative formulation of a logic model that describes her theory of change for creative placemaking: artists + love + authenticity -> creative placemaking. While I’d classify this as more of a definition of creative placemaking than a logic model, it goes a long way toward illustrating my point that we all have latent logic models in our head that are just waiting to be expressed as such. Laura writes, “there’s no logic model in the world that can capture how a crazy parade [the annual MayDay parade in Minneapolis] can restore my faith in humanity.” I couldn’t disagree more – in fact, I made one, relying solely on the way Laura describes the parade in her post. Here you go:

For the past few months, I’ve been researching impact assessment methods used across the social sector in connection with some evaluation work we’re doing here at Fractured Atlas. Seemingly every year, someone comes up with a new way of evaluating impact, whether it’s for social purpose investing, choosing grants, or measuring externalities. I’m not done yet, but what I’ve found so far has only reinforced my appreciation for the logic model. The beauty of logic models is that, because they relate so directly to the fundamental elements of strategy, they are endlessly adaptable to almost any situation. I actually find it kind of funny when people call logic models too rigid, given the alternatives – especially considering how much of our lives is ruled by the granddaddy of rigid, one-dimensional success metrics: money.

Awesome #3: Logic Models Are a Victory for Transparency

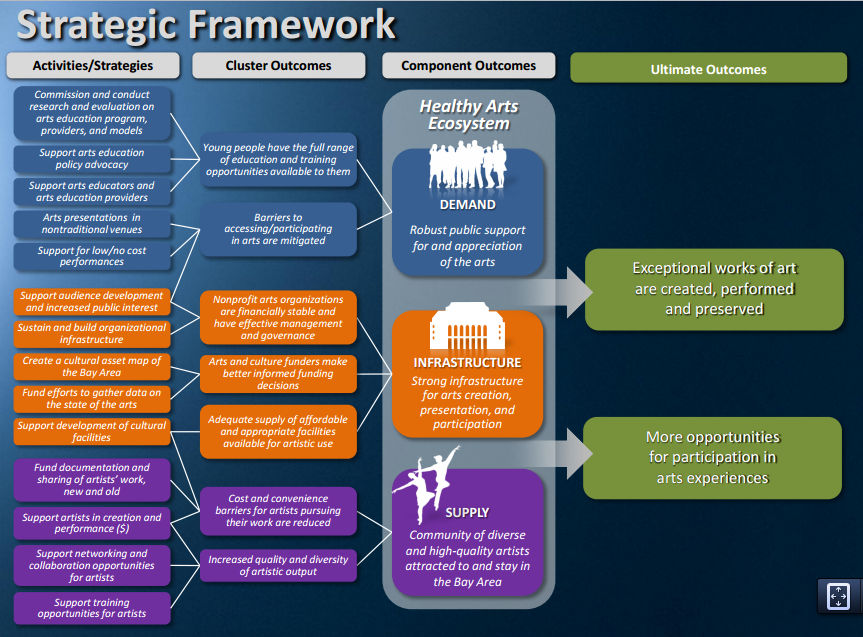

Hewlett Foundation Performing Arts Program strategic framework (co-developed in 2008 by yours truly)

One of the really powerful things about downloading the implicit strategy that exists in your head into a diagram is that it confronts you with gaps that may be present in that strategy and allows you to try and work through them. The Underpants Gnomes example that I used in my creative placemaking post is a great illustration of this. The Gnomes clearly felt that stealing underpants would lead to profit, but hadn’t clearly thought through the fuzzy middle part of the scheme. The Underpants Gnomes might seem like a fanciful exaggeration of the problem I’m talking about, but I would argue that there’s been more than one arts organization (and funding initiative) started with a similar lack of congruity between the proposed activities and intended results.

Diane Ragsdale is skeptical that logic models can serve this function, suggesting that funders might misuse logic models and turn them against their grantees. First, I think it’s important to make a distinction here: Diane and Arlene and Laura are all talking about logic models at the level of the individual organization/project. While I think these can be helpful, in my mind the most important logic model is the one for the funder itself. This is admittedly a rarer practice, but several foundations – such as Ford, Hewlett, McKnight, and Boston – have taken the steps of not only developing a logic model to describe their grantmaking strategies, but sharing that logic model publicly. Those that don’t publish at least sometimes make them available to peers outside the organization. Once a logic model is “out there,” there’s no taking it back. Therefore, logic models both pull back the curtain on a funder’s current thinking and also make it harder to project the illusion after the fact that a funder knew how things were going to work out all along.

Even more importantly, though, logic models are a victory for transparency with oneself, not just with others. The most important part of any logic model creation process is the set of assumptions revealed about how your program or organization works, and what it needs to be successful. Sometimes these assumptions might seem like no-brainers, and other times they will seem as unproven as they are central. Being comfortable with naming your assumptions as such is not just good practice for ensuring that your organization is constantly learning and growing. It’s also extremely helpful on a psychological level for dealing with the specter of possible failure. Because logic models explicitly draw a distinction between program design and program execution, they acknowledge the very real possibility that you could be doing your job perfectly and your program could still fail, because its theoretical foundation rests upon faulty assumptions. This is an incredibly freeing realization, because it means that radically changing or even scrapping a program that isn’t working doesn’t necessarily have to mean changing program leadership.

One of the reasons people sometimes feel anxious about evaluation and measurement is because they’re afraid of being held accountable, especially to things that they don’t have full control over or to metrics that don’t seem relevant to what they’re trying to do. When that happens, there are enormous incentives on managers and their supervisors to “cook the books” or otherwise game the system to show results that look better than reality, because any failure—even failures that are no one’s fault—reflects on them personally. That’s the danger of trying to enforce a data-driven culture without first developing the theoretical frameworks that determine what data you’re trying to collect. Because logic models separate the person from the program, they can distinguish between lagging initiatives that might just need more time to prove themselves, and failures of design that can be transformed into productive learning opportunities.

A Note About Logic Models and “Proof”

One of the criticisms directed at logic models generally, and by ArtPlace at my post specifically, is that they promote an impossible standard for proof. Here’s what ArtPlace had to say about it:

A critical limitation of elaborate logic models of the style developed by Moss is that it is nearly impossible to quantify or measure all of the different factors and relationships proposed. While many of the asserted relationships are plausible…almost none are measured in practice. Many – if not most – of the variables…could only be gauged imprecisely at great expense or are not susceptible of measurement at all. Multiply this problem by the 50 variables the model uses and the dozens of relationships it asserts, and it’s clear that it is beyond anyone’s ability to actually prove or disprove the model for even a single metropolitan area, much less the nation.

In one sense this criticism is right: these are difficult research challenges that highly qualified professionals have been struggling to address for decades, some of the more promising approaches demonstrated at the recent NEA/Brookings Institution convening on economic development and the arts notwithstanding.

But contrary to popular perception, the term “scientific proof” is a misnomer: proof is a concept germane to mathematics, not science. (Admittedly, my previous post could have been clearer on this point.) Scientists, including social scientists, develop hypotheses about how the world works and then gather evidence to support or undermine those hypotheses. Whereas proof is black-and-white, evidence has shades of gray: it can be strong or weak, circumstantial or conclusive. My colleague Kiley Arroyo made a great courtroom analogy in response to my creative placemaking post: she wrote, “think of forensic analysis if you will. You’re not just going to look at where and how the bullet hit, but what it was shot from, where, by whom and why.” Our job as researchers is not to “prove” anything – instead, it’s to amass evidence in search of the truth.

The biggest problem that I see with most logic models is that they are too simple for what they are trying to describe, and thus consign us to amassing a whole bunch of weak evidence. Logic models are often developed as much for communication purposes as for research, and can thus face intense pressure to be “dumbed down” for public consumption. I frequently hear comments like, “make sure that there are no more than five categories, because after that you’re going to lose people,” and God help you if your diagram doesn’t all fit on one page. But think about it, would you apply this standard to a budget? To a work plan? For a major, mission-critical project with many moving parts? I’m not interested in logic models as a communication tool; I’m interested in them as a means to help us do our jobs better.

In the case of ArtsWave, we do intend to collect data to show progress towards the goals that have been established through the model. But the task is less daunting than it looks. Because we are not trying to “prove” the model, not everything has to be measured directly; indeed, not everything has to be measured at all! Instead, the model serves as a road map for us in considering what is most important to measure, given what we don’t know. Is it that assumption that the arts can differentiate Cincinnati from its peer cities in the minds of tourists and potential residents? Can we be confident that people from diverse backgrounds will interact with each other if they happen to come together for the same community-wide event? A smart research design will test the assumptions that are most in need of testing, and the purpose of the modeling exercise is to identify which assumptions those are.

It’s not like we are all alone in this effort, either. There is an ever-growing body of literature on the ways that the arts interact with communities, and there is no need for us to demonstrate yet again connections for which strong evidence exists in other contexts. Furthermore, since many of the data points involve stakeholders beyond the arts, there is an opportunity to collaborate with other local entities to share resources and develop knowledge infrastructure collaboratively. Cincinnati is home to the STRIVE initiative, which has been made famous in the broader social sector as the poster child for the “Collective Impact” concept as coined by consultants from FSG Social Impact Advisors. One of STRIVE’s chief accomplishments has been the development of a “adaptive learning system” for use by hundreds of education nonprofits in the region, which has helped align the efforts of those organizations around a common set of purposes and benchmarks. If it worked in education, and in the same city no less, why can’t it work in the arts?

But that being said, none of the three benefits that I’ve cited above—articulation, flexibility, and transparency—require “proving” the logic model. They all come, at least in part, just from creating one. And creating a logic model doesn’t have to be a tortured, involved process. It doesn’t have to cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. You can write them out on a back of a napkin (okay, for some things you might need a really big napkin). Creating a logic model for something that will require a lot of your time or money is one of the most highly leveraged activities you can possibly undertake. I hope more arts funders will undertake it.