Investing in Creativity: A Study of the Support Structures for U.S. Artists (2003), an Urban Institute publication authored by Maria-Rosario Jackson, Florence Kabwasa-Green, Daniel Swenson, Joaquin Herranz, Jr., Kadija Ferryman, Caron Atlas, Eric Wallner, and Carole Rosenstein, sheds light on the economic and employment situation of individual artists in the United States following the cessation of NEA funding to individual artists in 1995. While not the first study on individual artists, it distinguishes itself by “providing a new and comprehensive framework for analysis and action, which views the support structure for artists in the United States as a system made up of six key dimensions of the environment in which an artist works.” Commissioned by the Ford Foundation and supported by consortium of 37 other funders, the study is notable for having led to the development of several concrete initiatives to increase support for artists, among them a comprehensive NYFA Source database and the Leveraging Investments in Creativity (LINC) initiative.

SUMMARY

The report begins with the premise that artists bring value to society, but “the public often views the profession of ‘artist’ as not serious. The way artists earn a living may seem frivolous, and artists are often seen as indulging in their own passions and desires which bear no relation to the everyday experiences of most workers. This too contributes to a devaluing of the artist as a citizen with the same rights and responsibilities as everyone else.” Investing asserts that artists should receive the same consideration and benefits as any other professionals.

Background and Methodology

Investing in Creativity reflects several years of research, including:

- Case studies of artists in nine cities (the primary source of data), featuring interviews with more than 450 people. The cities–Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Houston, Los Angeles, New York City, San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington D.C–were selected based on their large populations of artists, as well as the interest shown in the study by funders in those cities.

- A corresponding rural inquiry with two components: interviews with artists, arts administrators and funders operating in rural areas in California; and the convening of conferences of artists, arts administrators, funders and community leaders in rural areas in Nevada, New Mexico, New York, Maine, California, Kentucky, Missouri, and North Carolina.

- Expansion and analysis of an of a comprehensive database – NYFA Source – that provides national and local information on awards and services for artists, through a partnership with the New York Foundation of the Arts.

- A national poll of attitudes toward artists in the United States as well as site-specific polls in case study cities. This poll addressed additional issues related to demand for what artists do and how they are valued (or not) in our society.

- Advisory meetings with artists, leaders in diverse sectors of the arts, and researchers. The study authors attended various conferences and professional meetings for artists, vetted preliminary research findings at conferences, and continually investigated research in related areas.

Investing considers geographic location the primary framework in which to assess the supports available to artists –i.e., what is available in the artist’s local community. Recognizing that the cultural sector “doesn’t operate in a vacuum,” parts of the study also examine the arts in non-“arts” settings. For the purposes of the study, “artists” were defined as “adults who have received training in an artistic discipline/tradition, define themselves professionally as artists, and attempt to derive income from work in which they use their expert artistic vocational skills in visual, literary, performing, and media arts.”

Key Findings

One of the most important conclusions of Investing was that simply restoring cuts to government funding would not be enough to improve artists’ overall conditions. Instead, the research identified six core elements of an artist’s support structures:

- Validation: The ascription of value to what artists do.

- Demand/markets: Society’s appetite for artists and what they do, and the markets that translate this appetite into financial compensation.

- Material supports: Access to the financial and physical resources artists need for their work: employment, insurance and similar benefits, awards, space, equipment, and materials.

- Training and professional development: Conventional and lifelong learning opportunities.

- Communities and networks: Inward connections to other artists and people in the cultural sector; outward connections to people not primarily in the cultural sector.

- Information: Data sources about artists and for artists.

Investing in Creativity is broken into chapters on each of the six elements, each one describing in detail past research, current conditions, and future recommendations for each area. Rather than summarize each section individually, I will present what I see as the most salient themes in the overall findings:

Individual artists are undervalued by society, in comparison to art itself: while 96% of Americans value art in their communities and lives, only 27% value artists. This statistic is cited constantly in subsequent articles referencing this report.

Individual artists feel overshadowed and neglected by large urban institutions. Even institutions meant to serve local communities may not offer sufficient presenting or employment opportunities for local contemporary artists. Furthermore, “a general observation in all…cities was that on many fronts New York City sets the standards for critical review,” sometimes at the expense of developing a “local artistic heritage.” The authors urge the cultivation of stronger regional support systems.

Individual artists are frequently left out of arts-based urban planning initiatives (which tend to emphasize “large institutions and the traditional artist-audience relationship”): “Our review of city and cultural plans revealed that they tend to focus on the physical infrastructure of presentation venues –often to the neglect of artists’ contributions and needs.”

Artists’ societal contributions are not well understood, documented, or publicized, partly because of the inability of busy arts administrators to engage in reflective practice around this topic. Investing makes frequent mention of “the various ways in which artists contribute to society – as community leaders, organizers, activists, and catalysts for change, as well as creators of images, films, books, poems, songs, and dances” but acknowledges a lack of substantive data to back up these claims. Investing implies that if artists’ social and economic contributions were better understood and documented, it would be easier to make the case for supporting individual artists in various areas—for example, why artists need affordable workspace space as much as other low-income or “at risk” populations.

There is a perceived inequality of opportunities for artists (such as exhibitions or awards programs) based on factors such as race/ethnicity, and art form. For example, “several artists of color felt that large organizations seek them out only during designated times – such as Black History Month or Cinco de Mayo,” and folk artists and artists working in new media/technologies felt that mainstream galleries do not have structures in place for exhibiting their work. The study comments that “demographic, artistic, and career-stage diversity are not well served through mainstream awards, arts criticism, and media coverage.”

An artist’s career spans multiple markets and disciplines: “Artists do their work – sometimes simultaneously, sometimes over the course of their careers – in and across various parts of the arts and other sectors.” The report compares artists’ experiences across the nonprofit, commercial, public, and informal arts sectors. For example, the nonprofit sector is more conducive to risk-taking than the public or commercial sector. The sectors also interact; for example, artists may pursue more lucrative commercial work to support their more experimental nonprofit work. Furthermore, many artists contribute to non-arts fields like health and education, but this so-called “hybrid” work often goes unnoticed and lacks clear evaluation criteria.

Networks are extremely important in artists’ career advancement and support. Networks are, in fact, key to obtaining almost every type of resource in the six categories. While peers and “intermediaries” such as agents were most often mentioned by interview participants, partners outside the arts community are also essential arts advocates (such as anthropologists who ascribe value to immigrant artists’ work, or local sheriffs supporting artist-in-prisons programs). Partnerships with professionals in fields like real estate development or city planning can be especially valuable to artists, since artists usually lack the knowledge and skills to advocate for themselves in those arenas.

Many artists face the economic uncertainties of irregular employment. Some of the report’s findings on artists’ employment and material supports—that artists make little income from their creative work, juggle multiple part-time jobs to support themselves, and lack decent health insurance coverage in relation to the national average—are no surprise. Access to affordable work and living space is one of the major struggles. Contrary to popular belief, however, there is “little evidence that artists get a ‘thrill’ from risk-taking, or that they underestimate the extremely long odds of winning the jackpot of commercial success.” Rather, “artists feel an inner drive or calling to become and remain working artists, whatever challenges they may face.”

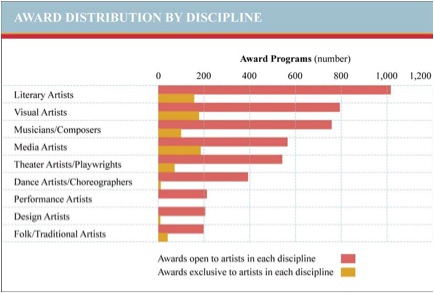

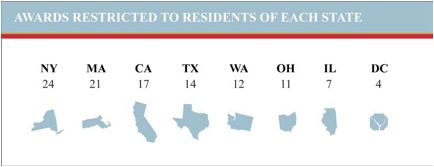

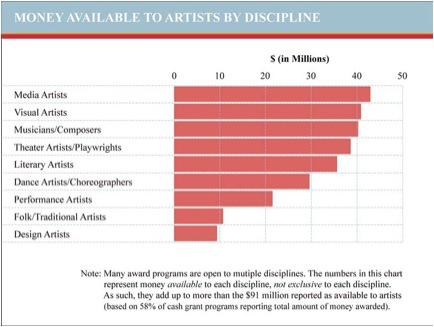

Grants and awards need to be more accessible, equitable, and relevant for artists. The report’s section on funding aggregates data on the different types of competitive awards offered specifically to individual artists, through a partnership with the New York Foundation of the Arts’ Visual Artists Information Hotline (which was to become NYFA Source). This section contains the most comprehensive quantitative data, as summarized in the tables below:

As seen in the above charts, this analysis identified clear discrepancies in awards available to artists; for example, “the small number of awards available to artists making work that does not neatly fit into categories based primarily on Western European standards is a problem.” Awards are also unevenly distributed according to artistic discipline and geographic region.

Many artists choose not to participate in the awards process, citing the difficulty of applying, the unlikely chance of winning, or the feeling of exclusion.

Training in the practical side of working in the arts, and in specialized or hybrid fields like arts education/community work, is limited in traditional universities. Training for artists should not be limited to artistic skills alone, but should encompass business skills and specialized skills for the “hybrid” sector. Especially notable is the fact that “unlike programs in law, medicine, and business, arts training institutions often do little job-matching and placement of their graduates.”

Various arts organizations, arts councils, and artist networks are meeting some of these artists’ needs described above, but these organizations need strengthening. In each of the six categories, the report cites some examples, in different cities, of helpful organizations and resources. However, programs that serve individual artists’ needs are vulnerable to funding cuts. Furthermore, sometimes organizations offer professional development for artists outside the scope of their regular programming, in a way that is not sustainable.

Investing in Creativity concludes with several “priorities for action”:

- Encourage better public understanding of who artists are, what they do, and how they contribute to society. This involves moving beyond an “art for art’s sake” argument for individual artist support.

- Strengthen artist-focused organizations that are already addressing the critical functions and deficiencies the study has identified.

- Establish broad-based networks of stakeholders at national, regional and local levels and convene those who are already working to improve artists’ support structures.

- Create an information clearinghouse that brings together existing research and data and can capture new information. Partner with university departments and policy research organizations doing similar research in all the fields identified as important.

- Strengthen the capacity of artists to advocate on their own behalf for the many crucial aspects of their support structure.

- Cultivate existing and potential diverse markets for what artists do and make—especially hybrid markets.

- Encourage changes in artists’ training and professional development to better address the realities of the markets in which they operate.

- Strengthen the awards and grants system by making the application process less cumbersome and more responsive to different artists’ needs.

The report ends on a hopeful tone, suggesting that its findings will “help to illuminate the condition of artists as well as promote the creation of a more comprehensive and robust environment making possible their contributions to society.”

ANALYSIS

Investing in Creativity provides a comprehensive summary of previous research on artists, new findings, and current gaps in our knowledge. It also suggests new ways to approach researching individual artists. Investing is thorough because of its research not only on what artists think, but on how artists are perceived by others. Because it was a multi-city study, encompassing not just diverse urban communities but rural regions, Investing has the capacity to highlight similarities and distinctions between different regions, and identify nationwide trends. As I will discuss shortly, Investing also led to the development of some concrete initiatives to help artists.

Despite these strengths, one of my main critiques of Investing is its failure to provide more detail on how the research was carried out. For example, while the report describes “fieldwork through more than 450 extended interviews with artists, arts administrators, arts funders, critics and media representatives, and selected persons outside the cultural sector, and in 17 focus group discussions around the country,” it does not provide any information on the selection of these groups. Similarly, the report lacks detail on how the national poll on attitudes about artists was distributed, and who actually filled it out (and whether the respondents can be considered a representative sample). At the least, appendices in the report showing the poll and focus group questions would have been helpful. Instead, the figures and charts from NYFA Source data are the most comprehensive quantitative information provided.

The framework for understanding and meeting artists’ needs is arguably the most helpful result of this study, as well as its emphasis on the overlapping spheres in which artists function. For example, recognizing that artists may work in more than one arts (or non-arts) sector is the first step for training artists in more viable career paths, or for building the types of services and networks that are appropriate for artists’ varied careers. The framework itself can be used in any geographic region in the future, to assess ability to attract and retain artists, and to identify opportunities for improvement.

The suggested action steps for arts organizations in the report are rather general, though the authors claim that they are not aiming to make a comprehensive set of recommendations. As I will explore in the “Implications” section, most of these suggestions have to do with strengthening access to opportunities for artists through better networking, cross-sector partnerships, information-sharing, and training, rather than radically altering the system of artist funding and employment.

The report was designed for its findings to be disseminated and funneled into concrete actions through continued partnerships with the funders and arts leaders in the different geographic regions of study. In this respect, it was remarkably successful, perhaps one of the most successful arts research initiatives in history. Three outcomes in particular—the expansion of the NYFA Source artist opportunities database from the New York Foundation for the Arts; the creation of the ten-year grantmaking and research initiative Leveraging Investments in Creativity; and the birth of the United States Artists grantmaking program—show a study whose impacts are still being felt long after its original publication.

Expansion of NYFA Source

According to NYFA’s website, NYFA Source originated as a phone service, the Visual Artist Information Hotline, founded in 1990. When this hotline caught the attention of the Urban Institute in 2000 during its research for Investing, UI collaborated with Carnegie Mellon University’s Center for Arts Management and Technology to create the new NYFA Source online database. According to the NYFA Source website:

The new database was conceived with several new features in mind. First, it was expanded to include programs serving artists working in all disciplines. Second, it was built as an online database allowing artists and other users to access customized, up-to-the-minute information 24 hours a day. And finally, it was built to enable funders and researchers to acquire information about patterns and trends in artists’ support…Today, NYFA continues to research and update information in NYFA Source…Additionally, as part of NYFA Source’s ongoing development, UI will regularly produce analytical reports about the patterns of support represented in the database. These reports will enable the arts field to monitor trends over time.

NYFA.org, which includes NYFA Source, is an essential resource for artists and organizations today, with information about more than 8,000 opportunities and resources available to artists in all disciplines. NYFA.org, much more than just an online awards database, is now functioning as what the report’s authors might consider an “information clearinghouse” convening a “broad based network of stakeholders.” As its website suggests, NYFA Source is also used for research purposes, to allow the continued monitoring of opportunities available to artists. According to Investing’s principal investigator Maria-Rosario Jackson, the Urban Institute did a follow-up assessment of NYFA Source in 2009, which verified its continued suitability for research.

Leveraging Investments in Creativity (LINC)

Investing led directly to the creation of Leveraging Investments in Creativity (LINC), a ten-year national initiative to improve the conditions for artists working in all disciplines. LINC funds, researches, and aggregates information about three core areas identified as key artist needs in the report: Creative Communities, Artist Space, and Health Insurance for Artists. According to Jackson, many of Investing’s 30+ funders, in particular the Ford Foundation, were committed in advance to “doing something about the results of this study,” though they left this open, based on what the study would reveal.

Reports/findings published since Investing, available on LINC’s website, illuminate examples of Investing’s recommendations put into practice. Most notably, the 2010 publication “14 Stories” summarizes the impact of LINC’s Creative Communities program in fourteen different cities. The programs, run by local arts nonprofits usually in partnership with non-arts agencies, are all providing a broad range of services for artists, strengthening training, networking, and material support opportunities.

One example is Cleveland’s CPAC – the Community Partnership for Arts and Culture. In a region striving to retain a vibrant artist community in the face of economic depression and unemployment, CPAC used its $190,000 LINC grant to found Artrepreneur, which sought to “treat artists like entrepreneurs.” In partnership with COSE, the Council of Small Enterprises, Artrepreneur morphed into the COSE Arts Network. “Over the course of three years, nearly 500 artists have either joined COSE outright or been reclassified as artists within the existing membership.” In exchange for annual dues, COSE helps artists access things like discounted health insurance, business and marketing workshops, and networking events.

LINC also conducts periodic research in target areas. One main area is health care; in 2009 LINC commissioned Helicon Collaborative to design and conduct an online survey of artists, administered through 40 different artist service organizations across the United States. Another study was conducted in 2010, forecasting the potential impact of Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (PPACA) on artists. Both studies also incorporated general data on artists’ employment. The findings in this report imply that artists’ overall insurance and work conditions have not changed substantially since Investing’s publication in 2003. For example, “artists who earn from 21%-80% of their income from their artwork are those most likely to earn under $20,000 a year…and are likely to have inadequate health care.” The report goes on to describe changes that could occur under PPACA and the crucial role of arts service organizations in equipping artists with information and assistance.

Whether or not artists’ conditions have fundamentally changed as a result of LINC’s work, it is commendable that Investing resulted in a structure for continually updating research in core areas, especially as new federal policies have arisen. Unfortunately, LINC’s 10-year run is slated to end in 2013, so this banner will need to be taken up by someone else if it is to continue beyond next year.

United States Artists Grants

Investing in Creativity highlighted the importance of large, unrestricted grants: “Many respondents told of the life-changing impact of a large fellowship and, more generally, of the relief from constant fund raising that a large grant provides…As well as remarking on the value of large grants, many respondents made the related point that they value grants of long duration, because they provide some relief from the uncertainty of having to continually piece together a living. Specifically, respondents indicated that they want multi-year funding.” This particular element of Investing is cited in the development of the United States Artists (USA) grant making program, which gives unrestricted $50,000 grants to artists in all disciplines.

IMPLICATIONS

Despite the commendable efforts and increased awareness that resulted this study, the report itself raised a few important questions for me:

Is it problematic to build a case for increased research and support for individual artists so heavily on the idea that artists benefit society?

Investing claims at its outset to be more focused on “artists’ contributions to society” than previous studies (and makes the broad recommendation that such contributions need to be better understood), but the report doesn’t offer many ideas for how to conduct such research—most of its statements about artists’ contributions seem to be assumptions or generalizations. The study is much stronger in its analysis of the working conditions, material supports and training available to artists. Though the purpose of Investing was not to develop a methodology for studying artists’ societal impact, is it dangerous to put so much emphasis on investing resources in an area that may not be easily researchable? There is a sort of chicken or egg dilemma in this report: the researchers seem to be relying on the “value of artists to society” argument to justify putting time and money into researching how to serve artists better—including researching the very question of why artists should be valued.

As an example: the chapter about artist space states, “In response to the question of why artists should get special treatment [around affordable space] when others are dealing with similar issues, for example, the case often rests on the assertion that artists are somehow special and intrinsically valuable to a community. This entitlement argument does not resonate particularly well with city planners when there is no hard evidence to back it up.” The report goes on to say,

The social impact argument that artists contribute to various aspects of community improvement such as social capital and civic engagement, crime prevention, youth development, and education is potentially the most persuasive to people who are already stakeholders in a community or potential stakeholders. But it cannot be made very strongly as yet because the contributions of artists are not well documented but rest largely on anecdotal evidence.

While the report does not offer any specific formulas for how to measure the contributions of artists, it suggests ways that the public can interact with and understand artists better, such as arts education and open studio programs.

I agree with the authors’ assessment that artists make important contributions to communities and deserve to be valued and treated as productive citizens. But I would also worry about this type of argument resulting in a bias toward supporting artists whose work has more obvious “functional” benefits, i.e. artists who teach youth, or create projects that generate a lot of tourism revenue in obvious ways.

To what extent does the report advocate for a radical overhaul of the current system?

Investing in Creativity pinpoints many challenges in the employment system for artists, yet never suggests that an entirely new system is needed. Instead, the implication is that conditions for artists can be improved through better information-gathering, networking, and training. But should we still only be “training” artists on how to get by in an employment system that is fundamentally flawed?

Investing mentions, in passing, some past government programs that provided more stable artists’ employment. For example, many older artists interviewed for this study lamented the end of the federal Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) of the 1970s. CETA opened up many new employment opportunities, even though “it was not an explicit arts-directed program.” I found myself wishing for more discussion of how CETA operated, and whether the United States government could institute something similar today, perhaps even a discussion of the WPA programs for artists of the Great Depression. Investing does not seem to call for a major shift in federal policy toward artists; instead it is primarily focused on strengthening local communities.

Arguably, the advent of social media, crowdfunding, and other recent, market-driven technological developments have had more impact on the way artists do their work than the policy-driven interventions coming out of this study. The report could not have anticipated the widespread use of social media platforms among artists in the years following 2003, but at least it highlighted the importance of online information resources like NYFA Source.

Another recurring theme in the report is that while there are some good awards and service organizations available to artists (for example, Creative Capital in NYC, CellSpace in San Francisco), they are not distributed proportionately to the number of artists in need. Even if artists were better trained in accessing resources, would there be enough to go around? For example, if the award application process were made even more accessible to artists across the board, would this just mean that more artists would apply and competition would be even steeper?

I was especially intrigued by the question, posed briefly by the report, of how artists can be better trained for sustainable employment, i.e. through university-level programs in more specialized fields like community arts—and how organizations can tailor mutually beneficial jobs towards artists. Some of the report’s most compelling personal accounts are from artists whose “day jobs” (even those completely unrelated to the arts) are actually favorable to their creative development. For example, teaching jobs where school administrations encourage integrating art into the classroom. Other artists find inspiration for their artwork’s content in mundane service industry jobs. This “day job” discussion has interesting implications for the field: for example, what if arts organizations designed more staff positions for artists that allow them to both work steadily in a teaching or administrative capacity, and receive things like health benefits and workspace in exchange? Should all artists be trained in more lucrative professions that can be done side by side with their artistic work? Beyond a limited number of unrestricted grantmaking initiatives, could there be other programs that pay artists to do creative studio work without a tangible end product?

Based on my own observations of artists, and current debates around artists as a creative labor force (for example, those raised by the Occupy Wall Street movement), it seems like the fundamental situation for artists has not changed significantly since this report’s publication—artists still face issues like underemployment, lack of affordable space, and the burden of grantwriting to support their non-commercial work. Nevertheless, Investing at least paves the way for more dramatic changes by suggesting ways in which the existing nonprofit sector can be better equipped to meet artists’ needs.

Further reading:

- LINC’s recommended research reports

- Maria-Rosario Jackson, Revisiting Selected Themes from the “Investing in Creativity” Study, The Urban Institute, 2009

- NEA Cultural Workforce forum, Friday, November 20, 2009 (which featured Jackson as a presenter)

- NYFA’s website contains up-to-date information about NYFA Source, as well as other listings helpful to artists, and recent articles about the business side of the arts that are helpful to all types of individual artists.

- Createquity, On the Arts and Sustainability