Informal Arts: Finding Cohesion, Capacity and Other Cultural Benefits in Unexpected Places (Chicago Center for Arts Policy at Columbia College, 2002) sheds light on the little-studied topic of adult participation in informal arts. The report was commissioned by the CAP in response to “The Arts & The Public Purpose” (American Assembly Consensus Report, 1997), the 1998 NEA Survey of Public Participation in the Arts, and a 1998 study from the University of Pennsylvania’s Social Impact of the Arts Project that identified a strong relationship between arts participation and other forms of community engagement. Given the CAP’s focus on the interaction of the arts and democracy, they approached Dr. Alaka Wali, Director of the Center for Cultural Understanding and Change at Chicago’s Field Museum to research the subject in more depth. The report, led by Wali along with ethnographers Rebecca Severson and Mario Longoni, follows participants in a dozen groups in the Chicago area, ranging from a drum circle to community theaters to a quilting guild. While there has been a lot of investigation into the economic impact of the arts and especially of those consuming it, this 431-page report delves into the social and artistic value created by people actually making art.

SUMMARY

Both the CAP and the Center for Cultural Understanding are centered around how the arts can be used for social change and engagement. Accordingly, the areas of inquiry set out at the start of the project revolved around community development. In the words of Dr. Wali, the areas were:

- What, if anything, does participation in these kinds of activities lead to in terms of interaction across boundaries of race, ethnicity, gender, and class?

- What kind of civic skills, if any, do people acquire as a result of their participation in these kinds of activities?

- What is the relationship between the informal and more formal arts?

Their research consisted of fieldwork (which involved joining each group as a student), review of media coverage, census records, published literature, and sending a survey to 310 participants (conducted via email and mail with 166 responses). Through these methods, authors found that the informal arts do help participants bridge differences with their peers and gain skills that are transferred to their work and civic life. Additionally, findings indicated that while the informal arts benefit from the formal arts in terms of training, inspiration, and (very occasionally) resources, the formal arts benefit from informal arts in that they serve as incubators and they create potential audience members.

However, the study also found that the informal arts are often “invisible” because they take place in unexpected spaces and don’t exactly have marketing budgets. The authors recommended that the informal arts be made more visible by being further studied, talked about by civic and arts leaders, advocated for, and used in community development.

What are the informal arts?

By now you may be wondering what exactly the “informal arts” are. The NEA Survey of Public Participation in the Arts calls them “unincorporated arts,” while many refer to them as amateur, leisure-time, or community arts. (Participants of case study groups described themselves as anywhere between “not ready for prime time” to “just people not professional”). The report’s official definition is that the informal arts are “creative activities that fall outside traditional non-profit and commercial arts experiences,” going on to say that they usually have no permanent home, virtually no fund-raising activities or secure income, and no selective membership.

To get a better idea, these are the groups that were studied in the report:

Benefits of the Informal Arts

1. Bridging Differences

Through a survey, the authors found that informal arts participants in the study were very representative of the US population as a whole across all groups in terms of income, ethnicity, age, occupation, and gender. Diversity within groups was also common, with the exception of ethnicity- groups tended to be primarily of one race.

Something significant that they had in common, though, was education—up to 80% had some college education (compared to 65.6% nationally). Another commonality was the love of or need to make art. There were more than 32 references in the field notes to artists saying they “have to” or “must” do their art, with the phrase “need to express” being used 72 times.

This common drive to make art provides a significant motivation to find other people with whom to make it, even if that means crossing social boundaries. The study devotes quite a bit of attention to how informal arts settings offer lowered barriers to participation that enable such boundaries to be overcome.

- The spaces were accessible and felt accessible. Of all of the case studies, not one was held in a space dedicated to art. Through their interviews and survey of media, the researchers found that the places where informal arts take place are coffeehouses, police stations, office buildings, churches, social service agencies, the street, libraries, and parks. The report spoke of underlying preconceived notions of “[the space] is there for me”(public spaces) v. “[the space] is there for others” (formal arts places). Some participants learned of the activities at parks and libraries simply when they were passing through, or saw the group practicing their activity through a window or outside.

- The activities were accessible financially. Most of the activities were free or low cost, with some participants specifically stating that they did not take classes at formal arts institutions because they were too expensive.

- The groups exuded and fostered a relaxed and welcoming atmosphere. Casual attendance policies prevailed—if someone had to skip a week, or even a few months, and it didn’t adversely affect the group, so it wasn’t a big deal. Older children would sometimes be brought along to avoid having to pay for a sitter. The atmosphere at group meetings was welcoming. Participants in the drum circle invited onlookers to join in, physically going up to them and handing them instruments. In the quilting guild, Asian music ensemble, and painting class, if a new member voiced concern over not doing the activity “right,” existing members would insist that they were doing fine and use self-deprecating humor to downplay their own ability.

- All talent levels were welcome in the groups. The painting class used the studio method in classes, in which the instructor goes from student to student, ensuring that everyone could work at their own pace. Participants could choose their own involvement level, and often the focus of their efforts—choosing which plays to produce was a group effort, and members of a painting class chose their own subjects and styles. There were opportunities for everyone from beginners to highly skilled artists. Participants taught each other peer-to-peer by sharing tips and tricks. Finally, teachers and peers were gentle on criticism, especially at first.

2. Building Capacity

The authors found that informal arts participation built skills that are useful in community development, including consensus building, working collaboratively, and the ability to imagine and foment social change.

Although decision-making styles varied across disciplines, all involved some level of consensus building. In the community theaters, decisions were made by the board or a director, but there was still discussion involved where everyone had their say, and eventually a majority developed. In the South Asian music ensemble, disagreements would be voiced via email, and later key members of the group would mediate, keeping the group focused on their purpose and goals. Even the church choir director, though he had official control over the selection of songs, would frame the selection as a request, saying “Can we sing this on Sunday?”

The participants reported learning collaborative work habits in their artistic activities and carrying those skills over into their work lives and the public sphere. For example, an actor found that because he had learned not to “take over” as a result of receiving criticism in theater, he could now more effectively play the role of mediator at work. A drummer spoke of becoming more egalitarian and more willing to join community groups because of his role facilitating the group rhythm of the drum circle, in which he encouraged people who thought they couldn’t play while keeping advanced and master drummers engaged.

Researchers observed both groups and individuals advocating for causes they believed in. One member of the writing group told the group’s sponsors that the journal they published was too “heavy” and stereotypically “ghetto drama,” and she convinced them to change it. A kindergarten teacher in the drumming circle initiated efforts to help the homeless through her school and spoke up more to her supervisors after joining the group. The authors of the study called this the ability to imagine and implement social change: a combination of the ability to form an opinion, to speak one’s point of view, and to be physically comfortable in the public sphere.

Informal arts participants frequently reported gaining other skills as well:

- 75% of respondents to the survey indicated that their ability to give and take criticism had improved since starting arts activities.

- 60% indicated that their problem-solving skills had improved; indeed, through their fieldwork, Wali et al. witnessed participants substituting materials, re-thinking strategies, and re-structuring roles in response to challenges that presented themselves.

- The authors recorded participants nurturing tolerance (especially regarding differing skill levels) and fostering mechanisms for inclusion using patience, humor, structuring of space (adding more chairs, etc), respect for people’s strengths even if their skills or experiences were less than one’s own, open-mindedness, and trust of strangers.

3. Strengthening the Entire Arts Sector

Despite the difficulty in defining terms and boundaries between the formal and informal arts—“amateur” and “professional” are words that describe employment status, but aren’t synonymous with talent level, for example—the authors found evidence of mutual benefit and reinforcement flowing in both directions. The formally trained teachers and group leaders often derived benefits from teaching such as new ways of thinking about techniques or ideas and hands-on experience in organizing and administrating. The students and less skilled artists benefited from the formal training of their teachers and gained inspiration from performances and exhibitions at formal arts institutions (50.9% of survey respondents replied that attending artistic events inspired their own artistic activities “very much”, 39.5% “somewhat”).

The benefits that flow between the informal and formal arts aren’t only felt by individuals. Wali et al. use the case of the Hull House to illustrate how the informal arts serve as an incubator for new ideas for the formal sector. Viola Spolin, the originator of American improvisational theater (a practice that culminated with Spolin’s son co-founding the legendary Second City comedy enterprise) started her career by attending classes at the Hull House with Neva Boyd, a Northwestern University sociologist who used dramatics, folk dance, storytelling and games to stimulate creative expression and self-discovery in children and adults. In addition, informal artists are frequently audiences for the formal arts. Some 45% of survey respondents indicated that they had seen displays or attended a performance at a college facility, 37% at a concert hall or opera house, 40% at a gallery, 58% at a museum, and 49% at a theater.

Invisibility of the Informal Arts

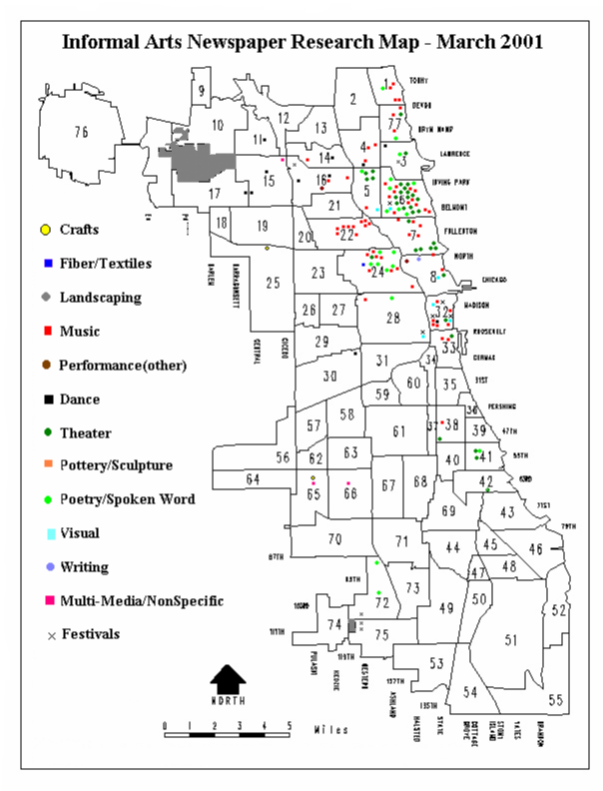

One of the most interesting findings of the report was that informal arts activities for the most part fly under the radar. Within their own neighborhoods, the groups were not well-known, and media coverage was uneven. Activities occurring in “artsy” neighborhoods were more visible in the media than activities occurring in neighborhoods where you wouldn’t expect it. The following two maps illustrate this dynamic. The first shows the informal arts activities reported in the print media during March 2001.

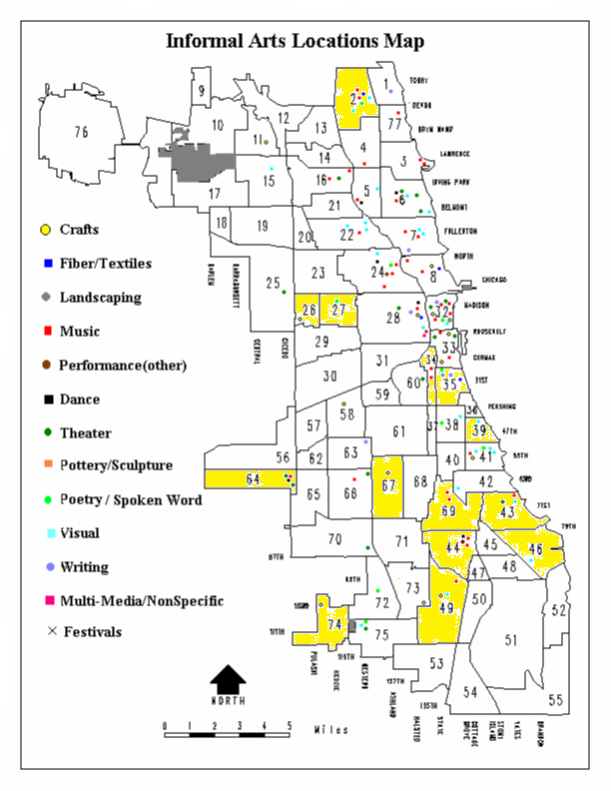

Now, here is a map of the three most frequently mentioned locations for informal arts, as described by participants at each of the case study sites. (In other words, this is a map of the informal arts as reported by word of mouth.) The districts in yellow have activities as reported by word of mouth, but not in the media.

As you can see from comparing the two, informal arts activities were actually happening in many areas of the city, not just primarily in affluent areas, as the map of media reports would have suggested. And it’s not just that informal arts activities are invisible to the public—they are invisible to each other, too. Researchers found no widespread recognition of informal arts practice as a concept within the informal arts world.

Recommendations

The study recommends several policy interventions to assist the informal arts in conveying their benefits to more individuals and institutions.

- Integrate arts practice in community development.

The researchers point out that most community development strategies revolve exclusively around physical infrastructure and economic development and ignore strategies that build on existing social structures. They say that informal arts groups are an important anchor in depressed communities, and suggest that incorporating these groups into an overall community development strategy that can foster creativity, problem-solving skills, civic-mindedness, and personal satisfaction. - Enhance access to informal participation.

Public officials and urban planners should expand resources, facilitate access and provide opportunities for informal participation and make this information as widely available as possible. - Build arts advocacy coalitions across informal-formal divides.

“If the arts are ever to be fully recognized for their contributions to the public interest, broader coalitions in support of the arts must coalesce across divides of professionalization and specialization.” Furthermore, within the study is an implied recommendation for formal arts organizations to initiate audience-building strategies and outreach efforts targeting the informal arts, for which they found no evidence at that time. - Make the informal arts more visible.

Civic leaders and leaders of arts communities should publicly recognize and remark upon the value of informal arts practice. - Collect missing data on social impact of the arts.

The study makes repeated calls for further study of informal arts and of social impact of all the arts to augment economic impact.

ANALYSIS

With its case study approach and in-depth qualitative research, this study was a landmark seven years ago and its findings are still startling and incredibly intriguing today. The methodology of the report is primarily qualitative ethnographic research balanced by quantitative evidence from a survey. The ethnographic research style is “participant observation,” in which researchers actually become members of the groups they study. This method allows the observers to compare subjects’ words with their actions. Their written observations (which form part of a 90-page appendix to the study) combined with interview transcripts were entered into a qualitative database management system. This system allowed for an incredibly detailed look at the data, allowing researchers to find things such as that “the code ‘need to express’ was used 72 times to mark passages concerning the compulsion artists feel to create.” The authors chose they case study method because they wanted a “bottom-up” perspective rather than a top-down survey of all the informal arts activity in Chicago. By exploring in-depth the dynamics of a relatively small set of groups, they were able to reveal the complex relationships among different participants, study sites, and arts institutions.

As explained in the summary, Informal Arts started out with three areas of inquiry:

- Did participation in the informal arts encourage people to interact with people different from them?

- Did participation build any skills in the participants conducive to community building? and

- What is the relationship between the informal and the formal arts?

Research and findings pertaining to the first two questions are susceptible to expectation bias: that is, researchers may expect a certain outcome (i.e., that participants do gain skills as a result of informal arts participation) and as a result may err in measuring the data toward that expected outcome. Certainly, this susceptibility to bias is why the researchers’ observations are balanced by interviews and the survey. But even those methods may suffer from response bias, which happens when a respondent provides the answers to questions that they think the questioner would find desirable. Observation is in turn meant to correct this bias by confirming what participants say with what they do. However, questions about past events (e.g., have your skills improved?) or motivations (e.g., how much has attendance at artistic events inspired your activities?), can’t be confirmed through observation.

In the text of the report, there is a lot of use of the words “seems to,” “apparently,” and “likely” when referring to causation. For example, “passion to create apparently leads people to search out and join groups regardless of their location or composition,” or “the mechanism for developing these skills [that build capacity] likely lies in the regular creation of art” (emphasis mine). On first read, it seems like the researchers may be jumping to conclusions, although it’s possible that their firsthand experience from interviews and observations convinced them of a causal connection that just wasn’t possible to generalize beyond the case study group.

In general, proving causation (especially when dealing with personal motivations) is very difficult. However, proof is a little easier when you have a control group. The report states that informal arts participation imbues skills in the participants such as collaborative work habits, consensus building skills, and the ability to imagine and foment social change. Without a control group, however, Wali et al. can’t claim definitively that arts participation caused people to obtain these skills, or that participants having these skills is not a result of self-selection. The report also says that the informal arts are a rich ground for formal arts audiences, but it can’t say that they make people more likely to attend formal arts organizations than if they did not participate. By comparing the results of the Informal Arts survey with the contemporary NEA SPPA data, we can start to get an idea about what that might look like. For example, 40% of informal arts participants reported seeing displays in the last 12 months at a gallery, and 58% at a museum. In contrast, only 27% of US Adults reported attending an art museum or gallery at least once in the same time period. This isn’t a true comparison, however, because this study asked people where they attended arts activities while the SPPA asked people what types of activities they attended.

It looks like those who participate in the informal arts are more likely to attend formal arts institutions, but without identical questions and methodology for the two groups, we really can’t say for sure.

Even looking at this report with the most skeptical eye, however, there are findings that stand out.

- Informal arts participants are surprisingly representative of the US population. In contrast to the skewed demographics typically seen among ticket-buyers to traditional arts events, the study found that people of all ages, races, incomes, and occupations participate in creating art (although they are usually slightly more educated). The importance of this takeaway to arts advocacy, if it proves consistent beyond the study, can’t be overstated: artists aren’t only weird people who make weird art that no one understands (like many who oppose funding the arts claim). They are ordinary people from all walks of life—your neighbor, your coworker, your relative—who have a need to create and express themselves.

- The informal arts don’t happen at arts institutions. Overwhelmingly (in Chicago at least) they occur in parks, libraries, and churches. This has some pretty big implications both for the non-profit arts sector and public policy (discussed below).

- The relationship between the informal and the formal arts is complex and fluid. Artists move from one end of the spectrum to the other, sometimes switching roles in the process, both by choice and by necessity. The informal groups can serve as incubators for new initiatives later picked up by formal institutions, and formal institutions in turn provide training and inspiration.

- The visibility of the informal arts is uneven at best and virtually nonexistent at worst. The maps indicate that there is a lot going on in economically depressed neighborhoods that isn’t noticed in the media. Furthermore, the lack of study in this area and the dearth of formal arts institutions reaching out to these groups suggests that the informal arts are underestimated and overlooked by those in positions of leadership in the artistic and academic communities.

IMPLICATIONS

When Informal Arts was published in 2002, “amateur” participation in the arts was just beginning to gain more prominence. In 2004, Demos published “The Pro-Am Revolution: How Enthusiasts are Changing our Economy and Society” describing people pursuing amateur activities to professional standards. Two years later, Chris Anderson came out with The Long Tail, about how the internet has increased consumer choice to the point that public interest is shifting to the long tail of niche interests. For pro-am artists, that means it’s easy to sell their art and find an audience online, through sites like CD Baby (c. 1999), Etsy (2005), FineArtAmerica (c.2008), ArtFire (c. 2010), or self-publishing with ebooks. Furthermore, the 2008 NEA SPPA found that 10% of all survey respondents reported performing or creating at least one of the art forms examined in the survey, up 2% from 2002. Recently, WolfBrown’s report “Beyond Attendance: A Multi-Modal Understanding of Arts Participation” explored the new and unfolding relationships between art creation, art attendance, and media-based participation.

More and more, people are participating in the arts virtually instead of in person. The internet has become another public space in which people participate in arts activities. In this case, access to technology and the web becomes another barrier to be lowered in order to enable arts participation. It would be very interesting to follow up with these groups or even conduct an entirely new study to see what impacts, if any, this revolution has had on informal arts groups’ activities, recruitment, and structure, as well as if this trend has prompted more formal arts institutions to reach out to the informal groups.

The researchers make the argument (and I am inclined to agree with them) that the study of informal arts participation is beneficial to the sector as a whole because it illustrates how arts practice creates value in individual and civic contexts, not just economic impact. By now, economic impact is the rallying cry for arts advocates. But economic impact reports are at best incomplete and at worst misleading about art’s impact on society. The arts create many types of value, not all of them monetary, and to successfully advocate for the arts we must try to measure as many as we can. There has been some study on the intrinsic value of art to audiences (WolfBrown), and innumerable studies on how the arts help children, but not very many on the intrinsic value of adults creating art. Informal Arts not only conducted a survey, but took an ethnographic case study approach to the study of arts participation to uncover what adults get out of their participation. To my knowledge this report remains the only study on this topic to go so in-depth with qualitative research.

So what are the implications of Informal Arts for the role of the nonprofit arts institution? None of the case study activities took place at a formal arts institution. I think that suggests that the majority of our arts institutions are viewed as places to consume art rather than to create it. Should they seek to change that perception to become viewed as places to create as well? The answer to this question will vary from organization to organization depending upon the resources and mission of each. But to ensure the future of any art form, there must be practitioners and consumers. And since practitioners often become consumers (and bring their friends with them), I believe it is in the long-term interest of arts organizations—large and small, presenting and producing, of all disciplines, including service organizations and arts councils—to encourage adult creation of art at the informal level. I see two primary ways for the arts sector to do this.

The first way is to enable existing informal arts groups in doing what they already do fairly well. The most common obstacle they face is a space to meet, which is available at any arts organization with a physical space. Sometimes groups need theaters, stages, or other specialized spaces (like community theaters and perhaps a choir or orchestra), but sometimes all they need is a room. And although many of the groups in the study weren’t hurting for members, participants themselves reported having trouble finding the groups in the first place. It wouldn’t cost much money for arts organizations to make it easy for patrons to find out about opportunities to create art in their specific discipline by calling the organization or visiting its website. In addition, if that institution were to partner artistically with informal arts organizations, it would recognize and validate that activity, encouraging the participants to continue and grow.

The second way is for the organization to directly engage in informal arts. This could mean having artists on staff give lessons, teach classes or facilitate groups (keeping in mind the financial barriers mentioned above). It could also involve reaching out to groups already meeting in libraries, parks, and churches and offering direct assistance in the form of teaching artists, funding, administration, or partnership.

__________________________________________________________

Although the field of arts research has barely begun to scratch the surface of the role that informal arts play and the ways they might impact the arts sector as a whole, it is clear is that the topic deserves more attention. Reading this report from the perspective of the formal arts sector, it’s a bit humbling to realize that the entire field plays only one part in the artistic life of the general public and our audiences. However, examining the benefits of informal arts participation as well as people’s motivations for doing it tell us a lot about the impact the arts have on society outside our walls. Given the constantly evolving patterns and definitions of participation (not to mention art), a better understanding of the informal arts will be increasingly valuable to both the arts and policy sectors now and in the future.

Further Reading:

- There’s Nothing Informal About It: Participatory Arts Within the Cultural Ecology of Silicon Valley. Maribel Alvarez, Ph. D. 2005

- Newsmakers: Alaka Wali, Director, Center for Cultural Understanding and Change, Field Museum: The Cultural Benefits of the ‘Informal Arts’. Philanthropy News Digest, 2004.

- Inside the President’s Studio: Alaka Wali (audio file). American Anthropological Association, 2010.

- Building Bridges at Chicago’s Field Museum. Art Works, the official blog of the NEA, 2010.

- National Endowment for the Arts Announces Research on Informal Arts Participation in Rural and Urban Areas. 2010.

- Culture and Urban Revitalization: A Harvest Document. Mark J. Stern and Susan C. Seifert, 2007.

- 2010 Cultural Engagement Index. Conducted by WolfBrown for the Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance.

- Cultural Engagement in California’s Inland Regions. Conducted by WolfBrown, commissioned by the James Irvine Foundation, 2008.