This particular Arts Policy Library entry is a bit of a reprise, since I read and discussed “Culture and Revitalization: The Economic Effects of MASS MoCA on its Community” for my independent study on public policy and the arts earlier this year. However, in recent months I’ve had a few experiences (including a session on community economic development at the Grantmakers in the Arts Conference last month) that suggest this study and its implications are less well known in the field than I would have thought. To help get the word out, I’m now doing a more complete analysis as part of the Arts Policy Library series.

This particular Arts Policy Library entry is a bit of a reprise, since I read and discussed “Culture and Revitalization: The Economic Effects of MASS MoCA on its Community” for my independent study on public policy and the arts earlier this year. However, in recent months I’ve had a few experiences (including a session on community economic development at the Grantmakers in the Arts Conference last month) that suggest this study and its implications are less well known in the field than I would have thought. To help get the word out, I’m now doing a more complete analysis as part of the Arts Policy Library series.

“Culture and Revitalization” is the economic anchor of a four-part multidisciplinary examination of the impact of the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA) on its hometown of North Adams, MA that also included historical/ethnographic, anthropological, and sociological approaches. The study was funded by the Ford Foundation’s Shifting Sands initiative and completed in 2005 by Stephen C. Sheppard, Professor of Economics at Williams College, along with co-authors Kay Oehler, Blair Benjamin, and Ari Kessler. Sheppard and his team are or were all associated with the Center for Creative Community Development (C3D), which began as a Ford Foundation initiative and has received additional grants and contracts from the likes of LINC and the Institute for Museum and Library Services to improve our collective understanding of the role arts organizations play in their communities.

Summary

North Adams is a small industrial town that was once home to vital textile and electronics firms that played a key role in the regional economy of Western Massachusetts. Thanks to the changing nature of industry and misguided urban renewal policies, however, the city began a steep economic decline beginning in the late 1960s. By the time the Sprague Electric Company closed down its factories in the center of town in 1985, North Adams was in bad shape.

It didn’t take long for the arts to step in. Thomas Krens, the erstwhile director of the Guggenheim who was at that time head of the nearby Williams College Museum of Art (WCMA), came up with an idea to repurpose the now-abandoned factory space in North Adams for large contemporary art works. Krens was inspired by an art fair he had attended in Cologne where dealers rented abandoned factories as exhibition space. He quickly won the support of North Adams’s mayor, John Barrett III, and the Massachusetts State Legislature approved a $35 million bond to build the facility in 1988. Krens installed his young WCMA colleague Joseph Thompson as the museum’s inaugural director.

The same year, however, Krens left to take over the reins at the Guggenheim, and for various reasons the project began to stall out. It wasn’t until 1995 that construction began on the facility and 1999 before the museum finally opened to the public, more than a decade after it was first envisioned.

This is where Sheppard et al.’s study steps in. Broadly speaking, the paper is structured around a kind of “before and after” snapshot of North Adams’s economy in the wake of the museum’s appearance on the scene, as variously manifested in employment figures, payrolls, housing values, and hotel tax receipts. In doing so, it takes full advantage of the natural experiment presented by the sudden infusion of $56 million in public and private funds toward the transformation of what had become a brownfield site into the largest center for contemporary art in the country.

The study begins with a helpful review of important recent cultural economics literature, including the work of Americans for the Arts, the Social Impact of the Arts Project (SIAP), the Urban Institute, and Richard Florida. The authors explain that each of these research efforts approach the problem of measuring the economic impact of culture from a slightly different angle, implying various advantages and disadvantages. For example, the approach employed by Americans for the Arts is easily ported to cities not included in the original study, but it focuses entirely on regional impacts rather than the arguably more important effects seen at the neighborhood level—a weakness shared by the Creative Economy Council’s report on the “creative sector.” SIAP’s work, by contrast, is lauded for its careful attention to spatial analysis, but is not as easily replicable in other settings outside of Philadelphia. The authors perceptively note that most of these efforts, whether focused on cultural tourism or Florida’s creative class, examine only one side of what is really a dual process: the long-term productivity potential of creative residents and the immediate benefits of discretionary spending by creative visitors. Interestingly, the authors also assert that Florida’s theories are of “little relevance” to rural areas and small towns, though they offer little evidence for this claim.

To understand the economic impacts of MASS MoCA in the greatest possible depth, Sheppard et al. employ several distinct tools. First, using employment data from the museum, an input-output model similar to that used in Americans for the Arts’s Arts & Economic Prosperity study is constructed via the Minnesota IMPLAN Group’s software package IMPLAN. As the authors explain, the language and framework of input-output models are familiar to policymakers and their results are loosely comparable between cities, but they miss a lot of depth due to overemphasis on regional effects and undercounting of artists and independent contractors. Nevertheless, the estimates provided by IMPLAN turn out to predict with almost eerie precision the actual growth in total local employment headcounts and payrolls in the years following the opening of the museum.

The authors’ input-output model reports a total increase in output of $9.4 million resulting from the museum in 2002, with $5.6 million of that total represented by museum expenditures, $1.9 million accounted for by expenditures on the part of other local businesses related to the museum (indirect effects), and another $1.9 million coming from the additional household expenditures of local employees supported by the museum’s and local businesses’ spending reported above (induced effects).[1] Using data from Americans for the Arts’s survey of non-local audience members’ expenditure habits as well as MASS MoCA’s own records, the authors estimate an additional $4.8 million of increased output resulting from audience spending on related items such as lodging, transportation, meals, etc., for a total yearly impact of over $14 million. The same model estimates an increase of 230 jobs throughout the local county economy as a result of MASS MoCA’s existence in 2002, with the bulk of the benefits accruing to the museum, restaurant, educational services, hospitality, and transportation industries.

Sheppard et al.’s model also provides estimates for revenue paid to the government as a result of MASS MoCA (even though the museum itself does not pay income or sales tax). “The government,” of course, is perhaps a misleadingly monolithic label: of the approximately $2.7 million per year attributable to MASS MoCA that goes to government coffers, more than half ends up at federal level, with the balance staying with state and local government. The biggest sources of this revenue are from personal income and social security taxes paid by/on behalf of new employees at the federal level, indirect business sales tax at the state level, and property taxes on improved real estate asset values at the local level.

A model means little, however, if it’s not grounded in reality. Fortunately, the authors took the time to compare the model’s outputs with actual trends in regional economic growth during the period following the museum’s opening. MASS MoCA’s own budget is well-forecasted by the input-output model, which makes its estimates based on the number of the museum’s employees. In 2002, MASS MoCA’s actual expenditures, according to tax records, were $5.56 million; the model’s prediction of $5.62 million (which forms the bedrock of its $14.2 million total impact estimate for that year) was therefore off by only 1%. Meanwhile, annual payrolls for the area increased a total of $24 million (in 2004 dollars) between 1998 and 2001 according to Census data. So in other words, the model implies that the birth of MASS MoCA was responsible for nearly 60% of the region’s net economic growth in the three years following its opening. Similarly, the model predicts an addition of 230 jobs to the county economy attributable to the museum; records show that actual job growth between 1998 and 2001 was 510. And if the average of the three years following MASS MoCA’s debut is used, the prediction of 230 new jobs comes even closer to the actual growth figure of 255.

In addition to total payroll and employee counts, Census employment data shows substantial increases in the average employee salary since MASS MoCA appeared on the scene. It appears that the museum helped bring more professional/white-collar workers to the city, with the average from the four years prior to the museum’s opening jumping from $24,991 to $27,114 in the three years afterwards (all numbers in constant 2004 dollars), an 8.5% real wage increase. Furthermore, there was a 12-15% increase in the number of small and medium businesses with fewer than 100 employees, particularly between 1998 and 1999 (the first year of the museum’s existence). The authors also examined the growth in hotel tax receipts to double-check the model’s assumptions about the impact of new cultural visitors to North Adams, and this time, they compared the numbers to those for surrounding communities. As it turns out, tax revenue for all of northern Berkshire County rose some 75% between 1994 and 2003—but the corresponding figure for North Adams was over 300%, far above that of any neighboring city or town. Both construction of new hotels and greater occupancy rates in existing facilities made the increase possible.

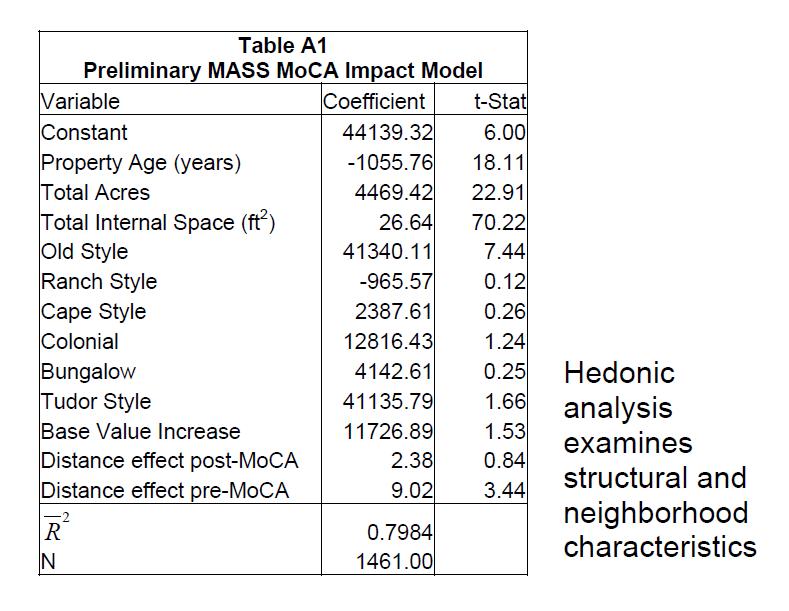

The true star of this study, however, is its innovative use of multivariate regression analysis to pick out the impact of MASS MoCA on local residential real estate prices. Sheppard developed aspects of this technique himself, based on the hedonic analysis pioneered by Ridker and Henning in 1967. Essentially, the team looked at actual home sale prices within a 2-km radius of the MASS MoCA campus (and the brownfield site that was there previously) during the period between the mid-1980s and 2003 and inferred the values of surrounding properties from what people were willing to pay for the ones that sold. The prices were normalized to the shelter component of the regional Consumer Price Index to cancel out any broader fluctuations in housing values during that period, and the regression analysis controlled for other variables that might influence prices on a house-by-house basis, including lot size, internal space, the age of the building, whether it was Tudor style, and so forth (full diagram below).

Sheppard et al. found that MASS MoCA did indeed appear to have an impact on real estate housing prices. Before the museum opened, properties closer to the MASS MoCA campus were actually less valuable than those farther out, because at that time it was a brownfield site with only the hulking remains of an electronics factory occupying it. For every meter further away a house was from the factory, its value went up by about $9. This result was statistically significant when controlling for the factors mentioned above. After MASS MoCA’s debut in 1999, property values still increased slightly with distance from the campus, but the value was much lower (just over $2 per meter) and the statistical significance disappeared (meaning that we can’t even say for sure whether distance from MoCA made any difference at all in a house’s price after 1999). Effectively, controlling for a whole host of other factors that might affect housing values, this means that the houses closer to MASS MoCA became a whole lot more valuable after that brownfield site was turned into a world-class contemporary art museum—to the tune of around $11,000[2] in the case of the properties closest to the action. The effect was noticeable out to a radius of about 1.7 kilometers (or just over a mile) from the museum. The authors estimate that the total rise in residential property values attributable to MASS MoCA was just shy of $14 million – and that number doesn’t include any increases in value that accrued to North Adams as a whole relative to surrounding communities because of MASS MoCA, or two extraordinary commercial investments (i.e., hotels) totaling $11 million that almost certainly would not have taken place if not for the museum.

Sheppard et al. found that MASS MoCA did indeed appear to have an impact on real estate housing prices. Before the museum opened, properties closer to the MASS MoCA campus were actually less valuable than those farther out, because at that time it was a brownfield site with only the hulking remains of an electronics factory occupying it. For every meter further away a house was from the factory, its value went up by about $9. This result was statistically significant when controlling for the factors mentioned above. After MASS MoCA’s debut in 1999, property values still increased slightly with distance from the campus, but the value was much lower (just over $2 per meter) and the statistical significance disappeared (meaning that we can’t even say for sure whether distance from MoCA made any difference at all in a house’s price after 1999). Effectively, controlling for a whole host of other factors that might affect housing values, this means that the houses closer to MASS MoCA became a whole lot more valuable after that brownfield site was turned into a world-class contemporary art museum—to the tune of around $11,000[2] in the case of the properties closest to the action. The effect was noticeable out to a radius of about 1.7 kilometers (or just over a mile) from the museum. The authors estimate that the total rise in residential property values attributable to MASS MoCA was just shy of $14 million – and that number doesn’t include any increases in value that accrued to North Adams as a whole relative to surrounding communities because of MASS MoCA, or two extraordinary commercial investments (i.e., hotels) totaling $11 million that almost certainly would not have taken place if not for the museum.

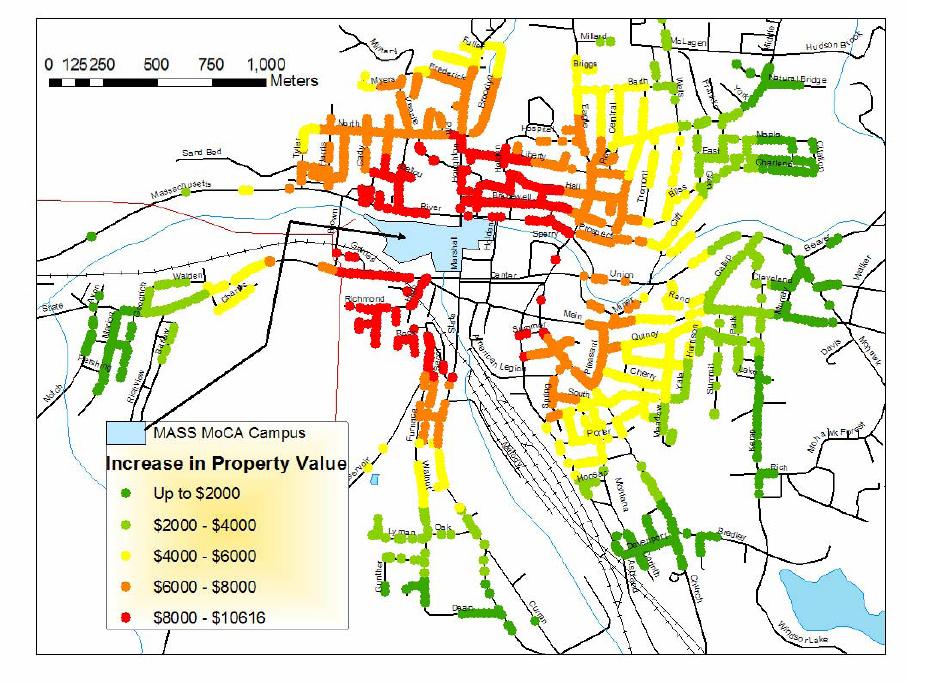

This is one of my favorite visuals ever, showing the increase in property values in North Adams attributable to MASS MoCA, as modeled by Sheppard et al. Each dot represents a single residential property and its predicted property value increase as of 2004 as a result of the museum. Note that the perfect concentric circles are a result of the linear nature of the model; the actual impact of the museum on each property would probably not be quite as neat, but should follow the same general pattern.

This is one of my favorite visuals ever, showing the increase in property values in North Adams attributable to MASS MoCA, as modeled by Sheppard et al. Each dot represents a single residential property and its predicted property value increase as of 2004 as a result of the museum. Note that the perfect concentric circles are a result of the linear nature of the model; the actual impact of the museum on each property would probably not be quite as neat, but should follow the same general pattern.

Analysis

This is really impressive work on a number of levels: from the earnest attempts to ground modeling in actual data, to the multipronged and multidisciplinary approach, to the savvy exploitation of the natural experiment afforded by the museum’s opening. The advanced regression analysis of real estate prices is particularly notable and begs for replication in other communities. An exceptional package of materials is provided alongside the study, even including a rudimentary cultural asset map of North Adams showing visitor origins against a backdrop of demographic data. At almost every turn, it is clear that the authors have thought through the full implications of what they are claiming, and done their best to explore alternative explanations and identify competing or obscuring factors. They take their social science seriously.

The fact that “Culture and Revitalization” covers the birth of an institution adds a significant degree of credibility to its conclusions. My objection to much of the analysis contained within Americans for the Arts’s Arts & Economic Prosperity studies, for example, is that it assumes that if an art organization disappeared tomorrow, all of its money and employees would disappear with it. To be sure, losing an organization is always a traumatic experience for the community, but the strong likelihood is that many of the employees would eventually find work with other employers; some might form new businesses or organizations, and so on. Indeed, in some cases it’s possible that an arts organization might even be standing in the way of a more economically efficient business environment taking shape. In the case of MASS MoCA, though, the city was under such duress and the investment was so centrally placed that it’s hard to imagine the impacts on payroll, jobs, and salaries observed in the study if the town had just stood pat. The people who moved to the area to work for the museum almost certainly would not have done so otherwise; the Porches Inn almost certainly would not have been built if there were no museum to draw tourists; etc. For these reasons, the input-output analysis carries far more weight here than it does in most other circumstances.

The fact that “Culture and Revitalization” covers the birth of an institution adds a significant degree of credibility to its conclusions. My objection to much of the analysis contained within Americans for the Arts’s Arts & Economic Prosperity studies, for example, is that it assumes that if an art organization disappeared tomorrow, all of its money and employees would disappear with it. To be sure, losing an organization is always a traumatic experience for the community, but the strong likelihood is that many of the employees would eventually find work with other employers; some might form new businesses or organizations, and so on. Indeed, in some cases it’s possible that an arts organization might even be standing in the way of a more economically efficient business environment taking shape. In the case of MASS MoCA, though, the city was under such duress and the investment was so centrally placed that it’s hard to imagine the impacts on payroll, jobs, and salaries observed in the study if the town had just stood pat. The people who moved to the area to work for the museum almost certainly would not have done so otherwise; the Porches Inn almost certainly would not have been built if there were no museum to draw tourists; etc. For these reasons, the input-output analysis carries far more weight here than it does in most other circumstances.

With that said, there are two parts of the study that I find less compelling than the others, which is why they are not mentioned in the summary above. First, Sheppard et al. attempt a return-on-investment analysis of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts’s initial $35 million bond issue that helped MASS MoCA get off (or, I guess, into) the ground. The analysis is based on a total annual return to government revenue of approximately $2.7 million based on figures from 2002 (this includes the estimates for residential and commercial property tax revenues driven by the museum). Without knowing the full details associated with the bond issue, I have to take the authors’ word that the public’s investment will pay off when taking inflation and growth projections into account. However, the bigger problem is that more than half of the $2.7 million in anticipated annual revenue is going to the federal government, not to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts or the city of North Adams. Even with some of that money eventually finding its way back to the state, it seems likely that the $35 million bond issue is actually resulting in a net outflow of public funds from Massachusetts to the rest of the country. For this reason, I find the authors’ case that “in fifteen years taxpayers will have recovered the initial investment” in MASS MoCA a weak one, at least from the perspective of Massachusetts taxpayers.

Second, the authors claim that North Adams has not suffered the negative effects of gentrification due to MASS MoCA’s arrival because the percentage of residents who have moved in the past five years actually went down nearest the museum between 1990 and 2000. There are all kinds of problems with this analysis (increased occupancy rates or new buildings could account for more people who have recently moved without implying any displacement; if displacement moved people into another neighborhood, they would show up in the new neighborhood rather than the old), but the biggest issue is that the data from 2000, barely a year after MASS MoCA came into existence, is not fresh enough to capture any serious displacement trends in the community. After all, the authors’ own models have the impact on real estate prices taking place from 1999 through 2003, or three times longer than the time window used for the gentrification analysis. We’ll need to wait for information from the next Census, in 2010, before this approach can shed any real light on displacement trends in North Adams as a result of MASS MoCA. (To their credit, the authors do note this deficiency in their approach, but that doesn’t stop them from declaring confidently that “MASS MoCA as made North Adams a better place to live without causing gentrification.”)

Implications

So, what’s the bottom line here? Did MASS MoCA cause the revitalization of North Adams or not?

Certainly, North Adams experienced a pretty impressive revival in close temporal proximity to the opening of the museum. The hardest part of any rigorous study in the social sciences, though, is establishing what’s known as the counterfactual: that is, what would have happened if MASS MoCA had not, in fact, been built? It’s not enough to look at action A and outcome B and conclude that A caused B. You can only know that if you know that B wouldn’t have happened anyway. Short of renting a time machine and assassinating Thomas Krens before he came up with the idea, there aren’t too many tools at our disposal to figure that out. One thing we can do, though, is compare MASS MoCA to communities that are similar in important ways: either by virtue of geographic proximity, demographic and historical parallels, or (preferably) both. “Culture and Revitalization” admirably takes steps in this direction for parts of the study, specifically for the comparison of hotel tax receipts which pitted North Adams against other towns in the Northern Berkshires, and for the real estate regression analysis by adjusting sale prices according to the shelter component of the regional consumer price index. One way in which the authors could have built an even stronger case would have been to compare trends in job creation, salaries, small business growth, and downtown real estate to a “sister city” or two that did not have a world-class cultural institution dropped into its center one year. It might not have been enough to establish conclusive proof (I’m not sure that will ever be a realistic goal with this type of work), but it would give us some pretty strong evidence to work with when considering policy decisions.

Even without this extra layer of evidence, though, the case for MASS MoCA’s role in the revitalization of North Adams is quite convincing, due largely to the absence of other obvious factors that could have explained the remarkable growth seen by the city following the museum’s opening. While it’s important not to overhype these impacts—North Adams is still a city with a lot of problems, after all, and residential properties are still more valuable if they are farther away from the museum as of 2003—to think that a single cultural institution could become this kind of an immediate force in a community is remarkable. A follow-up study, taking place perhaps early in the coming decade, would likely provide us with a richer understanding of the true extent of the museum’s transformative power, or lack thereof. In the meantime, the multidisciplinary companion documents prepared by the C3D team present the qualitative aspects of MASS MoCA’s regenerative properties in sharper relief, particularly the history of the museum’s inception (from which some of the material in the first section of this essay is drawn) and the paper describing the city’s neighborhoods and organizational infrastructure. An innovative fourth document uses social network analysis to describe MASS MoCA’s connectedness in the communities of North Adams and Williamstown relative to other prominent organizations. The museum ranks 7th-10th on various measures overall, and first among arts organizations.

This study demonstrates pretty clearly that arts organizations can provide strong economic benefits to their community. Before we get too excited, though, there still remain some unanswered questions. MASS MoCA’s situation—a huge, world-class facility coming into existence in an economically depressed city of fewer than 15,000 people—is highly unusual as arts organizations go. It’s unlikely, though certainly not impossible, that the birth of a single institution could meet with similarly dramatic results in other socioeconomic contexts. Furthermore, the study does not do anything to compare the arts with other types of investments. Remember, MASS MoCA would not have been possible without a $35 million bond issue from the state and over $20 million in other funds to pay for its construction. How much of North Adams’s revitalization was attributable to MASS MoCA itself and how much simply to the money that funded it? In other words, if $50 million had been spent on, say, converting the Sprague Electric Company site into a biotechnology office park instead, would we have seen the same results? “Culture and Revitalization” provides us with few clues.

Nevertheless, this study and its companion pieces represent an important, and under-recognized, contribution to the cultural economics literature. It is one of the only research reports I have seen that makes a convincing case not just that an arts organization was associated with economic revitalization, but that it caused the revitalization. That is no small thing, and policymakers and researchers alike would do well to pay heed to the methods and circumstances that made such a striking finding possible.

Further reading:

- Center for Creative Community Development, Economic Impacts of MASS MoCA (input-output analysis results)

- Kay Oehler, Stephen C. Sheppard, and Blair Benjamin, Mill Town, Factory Town, Cultural Economic Engine: North Adams in Context

- Kay Oehler, Stephen C. Sheppard, Blair Benjamin, and Lily Li, Shifting Sands in Changing Communities: The Neighborhoods, Social Services, and Cultural Organizations of North Adams, Massachusetts

- Kay Oehler, Stephen C. Sheppard, Blair Benjamin, and Laurence K. Dworkin, Network Analysis and the Social Impact of Cultural Arts Organizations

- Andrew Pincus, “When Can the Arts Revive an Economy?”

- Stephen C. Sheppard, Hedonic Analysis of Housing Markets

[1] Note that this construction and terminology diverges slightly from the Americans for the Arts model, which treats all local household spending (not just employees’) as just another industry in the matrix of local businesses. AftA also has a different meaning for “induced” spending, using the term to refer to audience expenditures.

[2] Several variations of this figure ranging from $9500 to $11,728 are seen in the report. It is unclear which of these represents the most accurate value.