For this first official installment of the Arts Policy Library, I wanted to start at the beginning. Gifts of the Muse: Reframing the Debate About the Benefits of the Arts was the first research study to be mentioned on Createquity, way back in the fifth-ever post published on this blog. The book’s concise, 104-page length belies grand ambitions: between the covers, the authors, Kevin F. McCarthy, Elizabeth H. Ondaatje, Laura Zakaras, and Arthur Brooks, attempt to catalog all of the public and private benefits that have been claimed for the arts, evaluate the strength of each claim, and tie it all together into a grand unifying theory.

For this first official installment of the Arts Policy Library, I wanted to start at the beginning. Gifts of the Muse: Reframing the Debate About the Benefits of the Arts was the first research study to be mentioned on Createquity, way back in the fifth-ever post published on this blog. The book’s concise, 104-page length belies grand ambitions: between the covers, the authors, Kevin F. McCarthy, Elizabeth H. Ondaatje, Laura Zakaras, and Arthur Brooks, attempt to catalog all of the public and private benefits that have been claimed for the arts, evaluate the strength of each claim, and tie it all together into a grand unifying theory.

The exhaustive literature review that went into Gifts of the Muse represents an invaluable service to the arts, even if, as the authors acknowledge, depth was sacrificed at times for breadth. With their eyes no doubt glazing over from consulting hundreds of sources in fields as diverse as cognitive psychology, linguistics, neurobiology, sociology, community development, public health, urban anthropology, political science, cultural economics, aesthetics, philosophy, and art criticism, the authors conclude that the evidence for so-called “instrumental” benefits is plagued with methodological weaknesses, and that a renewed focus on intrinsic benefits (also known as “art for art’s sake”) is in order for policymaking and advocacy purposes. But wait, there’s more! Not satisfied with simply analyzing the benefits of the arts, the authors attempt to devise a comprehensive theory for how individuals and communities access those benefits, and use this theory as the basis for several overall policy recommendations, the most significant of which involves a shift from a supply-side model for the arts toward the cultivation of more demand, specifically by investing in arts education.

Summary

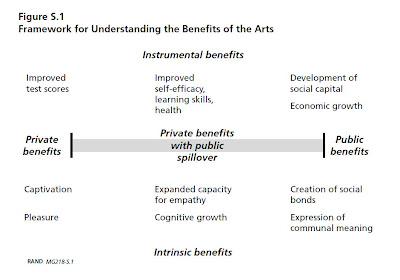

That the distinction between intrinsic and instrumental benefits of the arts seems so commonplace now is perhaps a testament to Gifts of the Muse’s impact. McCarthy et al. peg the rise in prevalence of instrumental arguments (that the arts are a method of producing non-arts-related positive outcomes) to the culture wars of the early 1990s, when public subsidy for the arts in America was very much under attack. The problem with using instrumental arguments to advocate for the arts exclusively, the authors argue, is that they ultimately privilege other policy objectives like economic development, public health, etc., leaving the arts vulnerable to evidence showing that other interventions are more effective at creating said benefits. While recognizing that the arts’ instrumental benefits may well be real and are not unimportant, the authors develop and advocate an integrated model combining instrumental benefits with so-called “intrinsic” benefits—i.e., ways in which the arts are the point, not a means to an end. In the model, each category is shown on a continuum from public to private, exploding the traditional association of intrinsic benefits with private individuals and instrumental benefits with the public at large. In so doing, the authors introduce the rather novel concept of public intrinsic benefits – in other words, benefits to arts participation that manifest themselves on a public level but are specific to art.

Most of the public discussion since Gifts’s release has focused on its call to the arts’ roots in intrinsic benefits, the basic pleasure they afford to large swaths of participants. But this only represents one aspect of what Gifts tries to do. Specifically, the authors:

Most of the public discussion since Gifts’s release has focused on its call to the arts’ roots in intrinsic benefits, the basic pleasure they afford to large swaths of participants. But this only represents one aspect of what Gifts tries to do. Specifically, the authors:

- Review the empirical research literature on instrumental benefits, assessing the strength of the evidence in each area

- Fill in some of the theoretical gaps present in the instrumental benefits literature

- Outline a theoretical basis for intrinsic benefits, and map out what the specific benefits should be

- Develop a theory for how arts participation happens, and why, and for whom

- Make policy recommendations based on all of these considerations put together

Needless to say, such a broad mandate does not lend itself to easy summary, which is one reason why this is (and probably will remain) the longest Createquity post ever. Just like life, Gifts seems to imply, research can be messy.

*

The meat of the report begins with a comprehensive taxonomy of the instrumental benefits that have been claimed for the arts, along with an analysis of the accompanying literature. Notably, the authors did not evaluate studies individually, instead synthesizing pre-existing literature reviews to build their case. Here is what they found in a range of areas:

Cognitive benefits (increased academic performance, test scores; improved reading/math skills, ability to learn)

The cognitive benefits literature is plagued by methodological weaknesses, particularly confusion between correlation and causation. A meta-analysis by Winner and Hetland (2000) found that only 32 of the 1135 studies they reviewed met their criteria for quasi-experimental designs (i.e., focusing on all arts rather than one discipline, using non-arts academic achievement as outcome variable, and including a control group), causing them to conclude that the overall evidence for cognitive benefits is weak. However, a few high-quality studies have shown strong positive effects for arts participation. For example, the work of Catterall (1998, 1999) demonstrated that not only did the cognitive benefits hold true within and between socioeconomic groups, but that the benefits increased as students in lower socioeconomic groups gained more arts exposure. Heath (1999) found similar effects on lower socioeconomic groups participating in community-based arts programs. The authors of Gifts of the Muse note that the much-ballyhooed “Mozart effect” (the benefit to spatial reasoning as a result of musical training) is real, but that the magnitude is small, the impact short-lived, and its importance questionable.

Attitudinal and behavioral benefits (increased self-discipline, self-efficacy, school attendance, perserverance; better understanding of behavioral consequences, working in teams; development of pro-social behaviors among at-risk youth)

Attitudinal and behavioral benefits are often conflated with cognitive benefits and studied together. Most of this literature focuses on youth, particularly at-risk youth. Many studies, including Heath (1999), found that hands-on participation is important in creating the benefits described. As with the literature on cognitive benefits, the studies tend to suffer from methodological limitations; even when a control group is used, the study is often limited to subjects in particular treatment program, meaning that the results are not necessarily generalizable to other populations or contexts.

Health benefits (improved mental and physical health among elderly, premature babies, and mentally and physically handicapped, and patients with dementia, Parkinson’s, acute pain, depression; reduced stress and improved performance for caregivers; reduced anxiety for patients facing surgery or childbirth)

The literature on health benefits of the arts is not well-developed. The strongest studies show a benefit to Alzheimer’s patients in delaying the onset and reducing the risk of dementia. Research on the other effects is generally weak, suffering from poor design or relying heavily on subjective information (for example, subjects’ self-reports).

Community benefits (increased interactions between community members, social capital, organizational capacity and infrastructure, civic engagement)

Most of the empirical study of community benefits has focused on informal/amateur arts. There is very little literature on audience participation or arts appreciation. Most approaches take the form of case studies, typically examining one form of participation and one type of benefit, rather than a comprehensive test of community asset-building. The authors note that the work of developing new concepts and methods for assessing how arts impact quality of life in communities is “in its infancy” but could yield “promising” results. The lack of longitudinal data is a big issue for this field, as is the task of isolating the impact of the arts from other social factors. These limitations make drawing substantive conclusions difficult.

Economic benefits (direct impacts: employment, tax revenue, spending; indirect impacts: the ability to draw high-value firms and workers to an area; public good benefits: increased quality of life)

According to the authors, the literature on the economic impact of arts is much more developed and boasts a longer history than that for the other instrumental benefits. The so-called “public good” economic benefits identified by McCarthy et al. include the “existence value” of arts availability, the “option value” of the ability to participate in them, and the “bequest value” of the opportunity to pass along the arts to next generation. Economic impacts on real estate prices would be included under the “option value” heading. Hedonic analysis and contingent valuation (asking people “how much would you pay for this?”) are two of the major research methods used. Despite its long history and established theory, cultural economic literature often receives criticism for the following reasons:

- The economic impacts are inherently difficult to measure, especially for public good and indirect benefits.

- Studies are usually conducted in urban environments, which may lead to bias/overstating effects by overemphasizing the role of tourists.

- Most studies do not consider substitution effects, or whether the money that is spent on the arts would have been spent on something else had not the arts been an option.

Of these three, the issue of substitution effects appears to be the most significant, one that the cultural economics literature as a whole doesn’t yet seem to have addressed convincingly.

*

Reviewing the literature on instrumental benefits in the aggregate, the authors notice a few patterns. First of all, a number of weaknesses in methodology plague the field, with the result that really good, useful studies are few and far between. The correlation vs. causation issue is a particularly problematic one for many efforts. In addition, many studies are so empirically focused that they fail to articulate a clear and specific justification for how and why the supposed benefits are taking place. Finally, almost all fail to take into account opportunity costs, or the extent to which the money, time, and effort put into arts activities could have produced similar or better results had they been channeled in a different direction.

It’s important to reiterate that a lack of strong methodology is not the same thing as an absence of impact. It is quite possible that these effects really do exist, and that the research has simply not, to date, done a very good job of demonstrating it. Furthermore, when it comes to cognitive, attitudinal, and behavioral effects, several strong studies have indeed shown such benefits for the arts, indicating that the case seems to have some weight. The authors note that when important positive effects have been demonstrated, they have tended to come with long-term, sustained involvement in the arts, rather than a single experience or sporadic participation.

Nevertheless, it is clear from the authors’ investigation that the overall field approach could use some re-examining. They make particular note of three meta-criticisms made by Paul DiMaggio, who dubs them “fallacies”:

- The fallacy of treatment (not all forms of arts participation produce the same effects)

- The fallacy of homogeneity (the same treatment may have different effects on different individuals)

- The fallacy of the linearity of effects (more treatment doesn’t always result in more impact)

*

Gifts of the Muse seeks to add to this literature in several ways. First, noting that much of the empirical investigation of instrumental benefits does not tie findings to any kind of underlying theory of why the effects are there, the authors try to fill in the blanks based on theoretical scholarship in a variety of fields. In doing so, they try their best to avoid DiMaggio’s three fallacies, though not with total success (as I’ll discuss in the following section). The first strategy is to distinguish various types of arts intervention, especially among youth, from each other. (The authors note that there is virtually no research on the cognitive, attitudinal, and behavioral benefits of the arts for adults.) McCarthy et al. categorize arts education programming into four types, with the following benefits theorized for each:

- An arts-rich school environment (improved attitudes toward arts and school, new role models/mentors, growth in self-confidence, self-efficacy)

- The arts as a pedagogical tool for learning (address diverse learning styles)

- Art as a means of teaching non-arts subjects (better understanding of history and social studies at high school level for students who have already studied the arts)

- Direct instruction in the arts

- Arts appreciation (almost no research literature on benefits)

- Creation of art (cumulative and integrative nature promotes and develops diverse skill set, helps students “learn how to learn” through enhancing self-awareness and monitoring capacity, develops project management skills enhancing self-efficacy)

The authors next examine the theory behind the public instrumental benefits to communities and economies. They divide community activity into three categories: creating art, appreciating art, and “supporting” art. The last category is a kind of catch-all for volunteering, donating, and leadership through board service. Participation via professional engagement in the arts (as staff or consultants) is not addressed. The authors theorize that the community benefits from creating art involve building a sense of community identity and trust through the creation of social bonds between participating members. Of course, art is not the only means of producing these benefits, but McCarthy et al. surmise that perhaps the communicative nature of the arts and the personal nature of creative expression may make joint arts activities particularly conducive to building social capital. This joint creative expression can be an effective means of promoting, preserving and communicating cultural heritage, a feature that other group activities cannot as easily reproduce. The benefits of appreciating art mostly arise from social bonds among subscribers and regulars created through same-group participation. The benefits from supporting art are seen by the authors to be much more substantial, involving specific competencies developed in volunteers and board members from running arts organizations and activities, and the collective efficacy made possible by bringing different groups together and forming connections between them. McCarthy et al. go so far as to claim that this last activity can lead to greater capacity for collective action and, eventually community revitalization. Notably, very few of the benefits described here are in any way specific to the arts; one could just as easily improve collective efficacy by bringing together other community constituencies for other kinds of shared activities.

Since the theoretical literature on cultural economics is already well-developed, the authors mostly stick to the benefits described in the empirical literature above, limiting their unique contribution to the development of a couple of models attempting to explain how the benefits happen. They do note that attendance at live performances and museums will have more of a direct economic impact than participation in community groups, simply because of the magnitude of the transactions involved. They also claim that the economic multiplier associated with the direct benefits of the arts is “essentially the same” across different industries, though I can’t determine the basis for this statement.

Since the theoretical literature on cultural economics is already well-developed, the authors mostly stick to the benefits described in the empirical literature above, limiting their unique contribution to the development of a couple of models attempting to explain how the benefits happen. They do note that attendance at live performances and museums will have more of a direct economic impact than participation in community groups, simply because of the magnitude of the transactions involved. They also claim that the economic multiplier associated with the direct benefits of the arts is “essentially the same” across different industries, though I can’t determine the basis for this statement.

This theoretical investigation indeed shows that not all arts programming efforts are equal. The strongest effects on young people are likely to come from direct, hands-on, sustained involvement in the arts, a notion backed up by both theoretical and empirical literature. Of the claimed cognitive benefits, the authors think that the case is strongest for enhancement of meta-learning skills, rather than specific non-arts subjects such as math. Furthermore, most arts involvement has a social dimension, and therefore possesses the potential for social capital creation. The economic activity associated with the arts certainly counts for as much as economic activity in any other field, but only programming that involves significant tourism and paid transactions will lead to substantial direct additions to the local economy.

This theoretical investigation indeed shows that not all arts programming efforts are equal. The strongest effects on young people are likely to come from direct, hands-on, sustained involvement in the arts, a notion backed up by both theoretical and empirical literature. Of the claimed cognitive benefits, the authors think that the case is strongest for enhancement of meta-learning skills, rather than specific non-arts subjects such as math. Furthermore, most arts involvement has a social dimension, and therefore possesses the potential for social capital creation. The economic activity associated with the arts certainly counts for as much as economic activity in any other field, but only programming that involves significant tourism and paid transactions will lead to substantial direct additions to the local economy.

*

Finished with instrumental benefits, Gifts of the Muse next dives into an extended discourse on the so-called “intrinsic” benefits of the arts, categorizing them as follows:

- Captivation (rapture, an intense and all-consuming experience)

- Pleasure (aesthetic satisfaction)

- Expanded capacity for empathy (increased receptivity to unfamiliar people, cultures, etc.)

- Cognitive growth (learning that problems can have more than one solution, that there are many different ways to see and interpret the world, and that neither words nor numbers can exhaust what we know, among other lessons)

- Creation of social bonds (the increase in intrinsic enjoyment of the art that can come from sharing it with other people; common language, shared experience)

- Expression of communal meaning (defining and/or communicating collective identity)

This work is highly theoretical, drawn from fields such as aesthetics and philosophy; very little empirical literature on intrinsic arts benefits exists. The authors developed their own theory for how intrinsic benefits work, shown below:

Importantly, the authors focus on arts experiences instead of works of art as the key unit of analysis. What makes for great arts experiences, they ask? The answer is emotional and mental engagement – the fuller, the more intense, the better. Put simply, they argue, no one actually participates in the arts for the instrumental benefits. People don’t say to each other, “you know, I want to contribute to my community’s capacity for collective action – maybe I’ll join a chorus!” People sing and dance and draw and act and write and read and volunteer and support and attend because art is awesome, on its own merits, on its own terms. More specifically, they participate because they get pleasure out of it – a pleasure that they can’t get anywhere else. All of these other things, the instrumental benefits, are great, but they wouldn’t be possible without the intrinsic benefits providing the motivation for people to participate in the first place.

Importantly, the authors focus on arts experiences instead of works of art as the key unit of analysis. What makes for great arts experiences, they ask? The answer is emotional and mental engagement – the fuller, the more intense, the better. Put simply, they argue, no one actually participates in the arts for the instrumental benefits. People don’t say to each other, “you know, I want to contribute to my community’s capacity for collective action – maybe I’ll join a chorus!” People sing and dance and draw and act and write and read and volunteer and support and attend because art is awesome, on its own merits, on its own terms. More specifically, they participate because they get pleasure out of it – a pleasure that they can’t get anywhere else. All of these other things, the instrumental benefits, are great, but they wouldn’t be possible without the intrinsic benefits providing the motivation for people to participate in the first place.

*

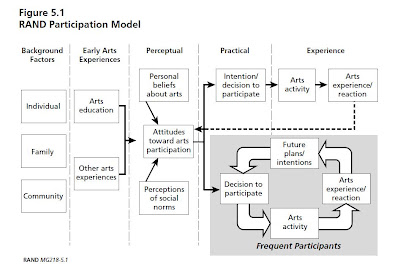

At this point we’ve covered both instrumental and intrinsic benefits of arts activity, looking at empirical and theoretical justifications for each. But how do people access these benefits? Why do they become involved with the arts in the first place? The next chapter of Gifts of the Muse explores these questions in depth.

The authors identify three stages of arts participation: gateway experiences that usually take place at a young age; occasional participation, involving an individual decision on whether or not to participate each time; and frequent participation, denoting the point at which the question shifts from whether to participate to how and when to participate.

Gateway experiences often come so young that they are not the choice of the experiencer. Perhaps they are participating in a mandatory arts education program at school, or their parents have arranged for them to take lessons on an instrument or take them to the art museum, or an important teacher or other mentor introduces them to the arts. If not given access to these experiences, a young person might first come into contact with the arts through pop music or films taken in with friends. Though it’s certainly possible for adults to become involved at a later age, it’s not a common phenomenon. The authors assert that the quality of the first arts experience is an important determinant of whether there will be another. It follows that almost all frequent participants in the arts will have had at least one truly compelling arts experience fairly early on, a hypothesis that fits with my own experiences and observations.

Given the theoretical and empirical emphasis on sustained involvement in the arts as a prerequisite for accessing the most important benefits, the authors spend some energy identifying what turns people from occasional into frequent participants. They define a continuum of aesthetic engagement ranging from boredom to relaxed entertainment to involvement to full engagement. The more engaged people are, the more likely they are to participate again, theorize the authors. McCarthy et al. also point out that the level of challenge must be appropriate to the level of competence that the individual brings to the task (whether it’s making art or appreciating it) in order to promote maximum engagement.

Given the theoretical and empirical emphasis on sustained involvement in the arts as a prerequisite for accessing the most important benefits, the authors spend some energy identifying what turns people from occasional into frequent participants. They define a continuum of aesthetic engagement ranging from boredom to relaxed entertainment to involvement to full engagement. The more engaged people are, the more likely they are to participate again, theorize the authors. McCarthy et al. also point out that the level of challenge must be appropriate to the level of competence that the individual brings to the task (whether it’s making art or appreciating it) in order to promote maximum engagement.

*

To conclude, McCarthy et al. indulge themselves in some policy recommendations based on what they found in the literature reviews and their theoretical exercises. The recommendations are as follows:

- Develop a language for discussing intrinsic benefits. The authors argue that given their importance, intrinsic benefits should not be left out of policy and advocacy discussions. Because they’re hard to measure, arts advocates will need to develop a qualitative, yet convincing way of communicating their worth.

- Address the limitations of the research on instrumental benefits. By this, they mean addressing the methodological weaknesses described in previous sections, as well as addressing DiMaggio’s three fallacies. The authors also advocate for further research into the nature of intrinsic benefits; as they note, “DiMaggio (1996) has demonstrated that empirical analysis can be conducted” on them.

- Promote early exposure to the arts. The specific suggestions include providing well-designed programs in the nation’s schools, avoiding “one-shot” experiences in favor of long-term, meaningful projects; supporting community-based arts organizations; and tapping into young people’s experiences with commercial arts (music, films, TV) as entry point for more formal arts education.

- Create circumstances for rewarding arts experiences. By building individual competence in the arts, developing individuals’ ties to arts organizations, and offering educational seminars to help people appreciate more challenging repertoire, the authors argue, arts advocates will grease the wheels for more productive and meaningful arts experiences.

In making these recommendations, McCarthy et al. hold that instrumental arguments are unduly focused on the supply of arts, meaning that they are primarily used as advocacy tools to scare up more money for nonprofit arts organizations. By contrast, what’s needed most from a policy perspective is a strategy to cultivate demand – because the ultimate goal, as they see it, is “to bring as many people as possible into engagement with their culture through meaningful experiences of the arts.” To do so, arts policymakers should “acknowledge the role of the commercial and community-based sectors in making the arts accessible to the public,” as well as invest heavily in arts education.

Analysis

Just as Gifts of the Muse’s contribution to the literature cannot be easily summed up in a paragraph or two, neither can my reaction to it. I will say that the document clearly represents a huge investment of energy, an extraordinarily ambitious project carried out with seriousness and professionalism. The review of the empirical literature is extremely valuable for helping everyone get on the same page regarding the benefits of the arts, and the theoretical frameworks by and large represent sound contributions to the conversation. The semantic distinction between intrinsic and instrumental benefits is useful, though given the way the report’s reception has played out, at risk of being overblown (the authors themselves admit that “not much is gained by separating the discussion of instrumental effects from that of intrinsic effects—the two are intimately linked”).

I’m most grateful to the report for hammering home several really important and not-at-all obvious points. First, the authors draw much attention to the fact that many of the positive individual and social impacts described for the arts can be replicated through other means. A community interest group can build social capital much the way that a chorus can; a sports stadium or new transportation hub can generate economic benefits too; we can teach kids to learn math better by having them spend more time on, um, math. Second, they point out DiMaggio’s three fallacies and explain how they apply to most of the existing research literature out there. The DiMaggio fallacies—particularly the fallacy of homogeneity, in my opinion—represent devastating critiques of applied social science research in all fields, not just in the arts. Finally, Gifts of the Muse wisely chooses to focus on arts experiences, rather than the art itself, as the defining unit for the discussion. In doing so, it implicitly acknowledges that the same work of art or the same art activity can have vastly differing impacts on different individuals. And it very correctly, in my view, hones in on extraordinary, fully engaging arts experiences as both the prerequisite and primary motivator for continuing arts participation.

With regard to the discussion of the arts’ instrumental benefits, I found little to complain about. In part this is because I don’t have much personal familiarity with the literature on the cognitive, attitudinal, behavioral and health benefits of the arts. In the social and economic realms, where I find myself on firmer footing, I considered the analysis basically on target, if a bit superficial in spots. For example, I was disappointed that creative class theory is barely mentioned by the authors, despite Richard Florida’s high profile at the time and the fact that their model for “indirect economic effects” is basically a mangled version of his argument.

Furthermore, the authors’ discussion of community revitalization through the arts and their bibliography reveal only a cursory familiarity with the work of Mark Stern and Susan Seifert at Social Impact of the Arts Project in Philadelphia. Both areas have seen a lot of exciting work undertaken since Gifts of the Muse was published five years ago, and the authors certainly can’t be faulted for not including it in their analysis; nevertheless, as a result, the sections on social and economic benefits now read as a bit dated.

Furthermore, the authors’ discussion of community revitalization through the arts and their bibliography reveal only a cursory familiarity with the work of Mark Stern and Susan Seifert at Social Impact of the Arts Project in Philadelphia. Both areas have seen a lot of exciting work undertaken since Gifts of the Muse was published five years ago, and the authors certainly can’t be faulted for not including it in their analysis; nevertheless, as a result, the sections on social and economic benefits now read as a bit dated.

Moreover, at least one knowledgeable observer finds fault with the treatment of cognitive, attitudinal, and behavioral benefits as well. Professor James Catterall, whose work is mentioned favorably several times in this section, wrote in a comment to a thread on ArtsJournal in 2005 that:

…the chapter on extrinsic benefits is held up as a literature review; it is clearly accepted as such, judging by the words of the invited panelists [in the ArtsJournal discussion]. However, it’s not. Only four specific studies are cited and actually discussed in the review of research on extrinsic benefits; and these four studies, the authors state, in fact reach valid positive conclusions about important extrinsic benefits. The arguments critical of research on instrumental benefits are not based, as reported, on the reviewing of research studies by the authors; they are drawn entirely from a study of studies by Project REAP (2001). REAP remains highly controversial; this is because every one of the academic effects reported in their good research syntheses was positive. This is curious – how could RAND get this wrong? I think they got it wrong by reading and quoting only REAP’s Executive Summary – not through an independent review of the underlying studies. Any conclusion that REAP found no instrumental effects of the arts simply doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

(Emphasis mine.) Catterall is correct about the dearth of actual studies cited in the text of the document, though reams of them are mentioned in the bibliography. Regardless of the validity of Catterall’s criticism, clearly the takeaway from Gifts of the Muse should not be that instrumental benefits don’t exist, or that they’re not important. Rather, the authors seem to want to play up the role of intrinsic benefits and qualitative arguments, which they feel have been neglected.

Once the authors get away from reviewing the work of others, however, their ventures into theoretical models begin to suffer from some fallacies of their own. For example, most of the discussion on participation seems largely rooted in an artificial supply vs. demand dichotomy from an earlier era (though creation of art is nominally included as a kind of participation). Generally speaking, the focus is on children and youth as makers of art and adults as appreciators of art. Yet the concluding recommendations on developing capacity for appreciation among adults make little sense in light of the authors’ own observation that hands-on experience is the most effective means of engagement for young people, and the almost total lack of research study on the benefits of arts appreciation. If sustained, hands-on participation is most effective for children, why would the authors assume the story is any different for adults?

Perhaps it’s because very little attention is paid to the benefits of arts participation to the artist, and almost none to professional artists. Furthermore, at no point do the authors acknowledge the sweeping societal and technological changes that have given rise to the Pro-Am artist, that peculiar breed of creator who works at a professional level but makes his or her living elsewhere. The extent to which artist and audience are more and more becoming the same people in different contexts is not discussed in Gifts of the Muse at all.

But these are still relatively minor points. The one major gaffe I found in Gifts has to do with a central premise: that the intrinsic benefits the authors identify are distinguished from instrumental benefits by virtue of their uniqueness to the arts. McCarthy et al. state that the intrinsic benefits are “inherent in the arts experience” and include “a distinctive type of pleasure and emotional stimulation.” The inference, it seems, is that the reason people participate in the arts in the first place (and the reason, therefore, to subsidize them) is because they can’t get these kinds of benefits anywhere else. Or at least that is the position implied by the authors’ withering criticism of the instrumental benefits literature for not considering the opportunity costs of supporting the arts to achieve broader policy goals.

In the course of their discussion of the intrinsic benefits, though, the authors let slip an interesting quote from one of the few sources directly cited in the chapter. It’s buried in a footnote on page 46, so the casual reader could be forgiven for missing it. But it casts a profound shadow over the entire discussion of intrinsic benefits. The footnote is drawn from Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s Creativity: Flow and the Discovery of Psychology and Invention, and is as follows:

When people are working creatively in the areas of their expertise, whether arts or nuclear physics, their various everyday frustrations and anxieties are replaced by a sense of bliss. That joy comes from what they describe as “designing or discovering something new” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1997, p. 108)

So nuclear physics counts too, eh? Indeed, elsewhere on the page, McCarthy et al. write “[Csikszentmihalyi]’s study of creativity is based on interviews with 91 exceptionally creative people from the arts, sciences, business, and government, [and] argues that we have underrated the role of pleasure in creativity of all kinds. His subjects all talk about the joy and excitement of the act of creation itself. But that enjoyment comes with the achievement of excellence in a certain activity rather than from the direct pursuit of pleasure.”

Huh. If I didn’t know better, I’d say that that sounds an awful lot like an instrumental argument for pleasure. As in, I get pleasure from the arts because I’m good at them, not because there’s anything so special about the arts. (There might be something special about the arts for me, but not in their capacity to be a source of this kind of pleasure generally.) Indeed, a closer look at the supposed intrinsic benefits for the arts reveals a similar pattern: almost all of them can be generated by lots of things besides just the arts. Captivation? If I’m running a race or performing delicate surgery, am I not equally captivated while doing so? Expanded capacity for empathy: does this not happen to me when I volunteer at a homeless shelter? Cognitive growth: could I not see many of the same effects from taking a class in computer programming or statistical analysis? Creation of social bonds: you’re telling me that playing on an amateur sports team, following World Cup soccer, going to Star Trek conventions don’t all do the exact same things? Expression of communal meaning: well, what the hell do you call religious services?

The entire chapter on participation patterns—everything from gateway experiences to frequent participation—could have written about any of a million hobbies and Pro-Am activities, from gardening to stamp collecting to astronomy to cooking and beyond. But curiously, the one “intrinsic” benefit that truly is unique to the arts—the creation of a space in society for experimentation and imagination for its own sake—is never mentioned. Nor is the capacity for communication between artists, either in the same generation or across generations, which allows them to cultivate a common language and heritage of aesthetic expression that is specifically about art itself.

Implications

I think all of this suggests a somewhat different lesson than the authors of Gifts of the Muse take from their literature review. Perhaps the salient point is not whether or not the arts produce benefits—of any kind—that are absolutely unique among all the various things that humans could be doing with their time or money. Perhaps the point is that, while running in a race can engender the same kind of personal pleasure, captivation, etc. as making art can, running in a race will engender nothing of the sort for me, Ian David Moss, because I suck at running. Or that while arts education on average produces small effects and/or statistically insignificant impacts on the grades of large populations of students, it might actually save one student’s life. Should we cast out such huge impacts on specific people because they’re statistical outliers?

In a way, the authors have, despite their best efforts to the contrary, fallen prey to DiMaggio’s second fallacy—the fallacy of homogeneity. For while they talk at length about how arts experiences will have different impacts for different classes of individuals – those who have been exposed to it early in their lifetimes, for example, or those who are already frequent versus infrequent participants – there’s never a real acknowledgement that even very similar people in similar contexts can have very different arts experiences. I love classical music more than most, but I don’t think I’ll ever find Handel especially compelling. I remember having brutal arguments with my composer friends back in school over the quality of the piece we had just heard in concert. The fact is, the arts are one giant sea of different strokes for different folks—and if that’s the case, then why assume that there’s anything universal about the arts as a whole?

I guess what I’m trying to say is that maybe the arts aren’t for everybody—and maybe that’s okay. We should be glad that they produce all of these various benefits for some people, especially those who might have a hard time getting those benefits elsewhere, and equally happy that there are many opportunities for individuals who don’t connect to the arts to express their creativity and strive for excellence and seek to understand the world around them in other contexts. And maybe the policy justification for supporting the arts on a participation basis is simply this: everyone who wants to should have the opportunity to participate in the arts , which means that people who can’t afford to do so themselves should be given the assistance they need—including, I suppose, the artists. Similarly, people who want to participate in sports, hobbies, etc. should be given that opportunity as well. But I don’t necessarily agree that the goal should be “to bring as many people as possible into engagement with their culture through meaningful experiences of the arts.” I don’t see how that represents success, unless that’s what those people want for themselves.

Further reading:

- Andrew Taylor, Gifts of the Muse (The Artful Manager)

- Mike Boehm, Arts Funding Report Sparks Controversy (Los Angeles Times)

- Eric Craig, Gifts of the Muse (The Usable Blog)

- Jerry Yoshitomi, Is Knowledge in the Right Places? (Grantmakers in the Arts Reader)

- John Stoehr, Reports Spar over Economic Impact of the Arts (Savannah Morning News)

- Robin Pogrebin, Book Tackles Old Debate: Role of Art in Schools (New York Times)