I’ve had a chance to look at the two papers that Richard Florida and his colleagues sent to me in response to my essay from last month criticizing the quantitative methodology used in his best-selling book, The Rise of the Creative Class. The short version is that (a) a lot of work has been done on this since that book was published; (b) generally speaking the creative class does seem to predict economic growth reasonably well, and at least sometimes more accurately than traditional human capital measures; (c) on the other hand, it remains unclear how much Florida’s other theorized inputs, especially his Tolerance index, contribute to creative class concentrations.

I’ve had a chance to look at the two papers that Richard Florida and his colleagues sent to me in response to my essay from last month criticizing the quantitative methodology used in his best-selling book, The Rise of the Creative Class. The short version is that (a) a lot of work has been done on this since that book was published; (b) generally speaking the creative class does seem to predict economic growth reasonably well, and at least sometimes more accurately than traditional human capital measures; (c) on the other hand, it remains unclear how much Florida’s other theorized inputs, especially his Tolerance index, contribute to creative class concentrations.

I’ll do a close reading of each paper in turn, then offer some concluding thoughts.

I. Marlet and van Woerkens

The first paper, authored by Dutch researchers Gerard Marlet and Clemens van Woerkens, compares creative class theory to human capital theory (human capital means the collective skills of a population, often represented by the percentage of adults with a college degree). This is the same question that was considered by Ed Glaeser in his review of The Rise of the Creative Class. Glaeser found that human capital was a better predictor of population growth in the set of US metropolitan areas mentioned in Florida’s book, though he did not look at employment growth.

Marlet and van Woerkens find that the creative class concentration in 1994 was a significant and reliable predictor of employment growth from 1994-2003 in Dutch cities. Notably, they find that this effect seems concentrated in urban areas; regional creative class share does not impact employment growth within the city. They test two different formulations of the creative class, Florida’s liberal definition which comes out to about 35% of Dutch workers, and a tighter definition leaving out people like secondary school teachers and government administrators. The two definitions perform similarly to each other. The authors also tried to disentangle causality by examining “exogenous” variables such as theater and musical performances, proximity to nature, quality of restaurants and secondary schools, number of students, and so on. I’m not totally convinced by this analysis since, as the authors acknowledge, many of these variables are probably influenced by creative class concentration as well, but it’s interesting to consider.

Marlet and van Woerkens also tested the creative class statistic against the concentration of people with Bachelor’s degrees, and found that the creative class was a better predictor of employment growth than human capital, with both a higher coefficient and stronger statistical significance. These results are replicated with different sets of years and when specific variables in the model are left out.

Finally, the authors looked at the Bohemian index (the concentration of artists in an area) and found that, while it does seem to have some explanatory power for employment growth over and above the creative class, this effect disappears when Amsterdam is removed from the sample. Perhaps Amsterdam’s status as a “world city” enables it to take advantage of artist concentrations in a way that smaller population centers cannot.

Marlet and van Woerkens conclude as follows (emphasis mine):

Members of the creative class are essentially working, but not necessarily highly educated, while highly educated people are not necessarily doing any work at all. Highly educated people might end up without jobs after studies, or choose for easy routine jobs, leaving their human capital largely unused….Levels of human capital can therefore be higher in places with more people working in creative jobs than in places with the same levels of education but less people working in creative jobs – not only because individual levels of skills and knowledge grow, but because everyone is making more and better use of other people’s knowledge. This means that the use of human capital may be more productive in places where more highly educated, creative people are living and working. Equal levels of human capital can, in other words, have different production outcomes due to different ways in which human capital is actually used: ‘working human capital’ is more productive than ‘non-working human capital’.

We suggest that it is not creativity in the sense of painting or making sculptures that makes Florida’s creative class responsible for regional growth differences. In our view creativity is the creative use of skills and knowledge. Defining creativity in this way makes the creative class an indicator for human capital.

Our overall conclusions are that Creative Class is theoretically much the same as Human Capital. To that extent we agree with Glaeser’s comment on Florida’s popular book. At the same time, the Creative Class standard – and this is precisely what Florida said in his ‘Response tot Edward Glaeser’s review’ – is in the Dutch case “a slightly better handle on actual skills, rather than using only an education-based measure – to measure what people do, rather than just what their training may say about them on paper”. By introducing the concept of Creative Class Richard Florida has found better standards for measuring human capital than the often-used education levels, this being his major (perhaps only) contribution to a better understanding of regional growth.

So that answers one question. But what drives the creative class to a particular area versus another? Marlet and van Woerkens followed up with another paper in 2005 entitled Tolerance, aesthetics, amenities or jobs? Dutch city attraction to the creative class. The co-authors understand that of Florida’s “3T’s,” the Tolerance indicator is really the linchpin of the three. (“Talent” is, after all, just human capital, which we’ve demonstrated above to be more or less the same as the creative class; and the idea that people who specialize in technology would gravitate to places with technology firms seems rather tautological.) Marlet and van Woerkens find none of the tolerance subcomponents (gay concentration, artist concentration, or pub closing hours) to be statistically significant in explaining the share of creative class workers in a city, and only one (artists) statistically significant in explaining creative class growth–and that in the wrong direction!

Rather than stop there, however, Marlet and van Woerkens go on to construct their own theory of what attracts creative class workers to the same place. In contrast to the “bohemian index” concept of concentration of artists, the co-authors find instead that the number of live performances per 1,000 residents is highly predictive of creative class concentration. This suggests that it is not self-defined artists but rather artistic activity that drives this growth (though when looking at actual creative class growth, performances lose some significance). Other significant drivers include proximity to nature, proximity to jobs, and the historic nature of buildings in the area. Each of these factors has an independent, positive association with creative class concentration. The co-authors go so far as to create an “amenity index” that has more robust explanatory power for this variable than any other single factor.

These papers are great. They are both quite readable, even if you don’t understand the numbers, and the analysis is, as far as I can tell, thorough and theoretically sound.

II. Florida, Mellander, and Stolarick

The major contribution of this paper, Inside the black box of regional development (purchase only — an earlier, free draft is available here), is to introduce a “stage-based” model that looks at the development process as a multi-step evolution rather than a simple cause and effect. Quoth the authors:

Our modeling approach is designed to address a significant weakness of previous studies of the effects of human capital and the creative class on regional development. Most of these studies use a single equation regression framework to identify the direct effects of human capital and other factors on regional development. The findings of these studies, not surprisingly, indicate that human capital outperforms other variables. But that does not establish that these other variables do not matter. First, something has to affect the initial distribution of human capital. Variables that have not performed well in other studies may exert influence by operating through human capital and thus indirectly affect regional development, or certain variables may operate through different channels. By using a system of equations our model structure allows us to parse the direct and indirect effects of key variables on each other as well as on regional development.

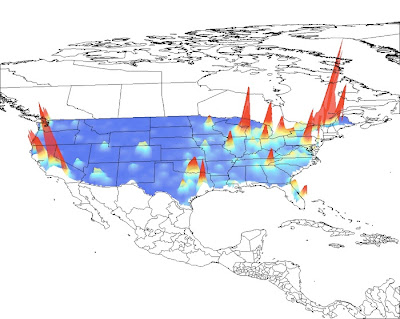

This new “path model” represents a bit of a departure from the theory presented in The Rise of the Creative Class. While the “3T’s” are still in evidence, Florida, Mellander and Stolarick now add universities and service amenities into the mix, as follows (click to enlarge):

As far as the human capital vs. creative class question goes, the co-authors make a useful, if slightly confusing, distinction between income (money received from mostly passive sources like investments and royalties) and wages (money earned from salaries, tips, and the like). They find that human capital is associated more strongly with income, but that the creative class has a stronger relationship with wages. No attempt is made to connect either metric with employment growth.

As far as the human capital vs. creative class question goes, the co-authors make a useful, if slightly confusing, distinction between income (money received from mostly passive sources like investments and royalties) and wages (money earned from salaries, tips, and the like). They find that human capital is associated more strongly with income, but that the creative class has a stronger relationship with wages. No attempt is made to connect either metric with employment growth.

So what did they find? In a series of structural equation models (SEMs), not surprisingly, the “Talent” factor scored the best in predicting both wages and income. The co-authors used three different measures of talent: human capital, creative class concentration, and the super-creative core. Of these, only human capital performed well in predicting income but all three were reliable inputs into wages. In all cases, the relationship between Technology and income/wages seemed pretty weak, never getting above a correlation of .36. Tolerance varied wildly; in the version with income as the dependent variable and the super-creative core as the talent indicator, the correlation was as high as .46, but in the version with wages as the dependent variable and human capital as the talent indicator, the relationship was totally insignificant.

How about the factors that draw the creative class to a region? Taking the model that shows the strongest case for creative class theory, the creative class/wages version, we see that tolerance and universities seem to have decent, though not extraordinary correlations of .36 and .32 respectively. Service amenities have a statistically significant but low correlation of .16 with creative class concentrations.

Notably, in the above construction the R-squared for the Talent indicator is very weak, at .332 (for the super-creative core it’s even weaker, at .316). That means that only 33% of the variation in Creative Class concentration in a region can be explained by the combination of Tolerance (i.e., gay and bohemian concentrations), university faculty concentration, and service amenities. Human capital is much better explained by these factors, driven by a much stronger correlation between the Tolerance measure and human capital. I suspect, based on other reading I’ve done, that this is simply because artists and openly gay individuals are much more likely than the general populace to have college degrees.

In case the above three paragraphs were gobbledy-gook to you, the plain English version is that while the analysis contained in the paper is a head-and-shoulders improvement over that contained in the book, it still doesn’t really tell us all that much. The major weakness comes down to causality; even the authors admit that

the graphic picture of the structural model (Figure 1) expresses direct and indirect correlations, not actual causalities. Rather, the estimated parameters (path coefficients) provide information on the relation between the set of variables. Moreover, the relative importance of the parameters is expressed by the standardized path coefficients, which allow for interpretation of the direct as well as the indirect effects. We do not assume any causality among university, tolerance and consumer services but rather treat them as correlations.

Though it’s a stretch to say that the Marlet/van Woerkens article establishes causality beyond doubt, at least that paper uses employment growth over a period of time as the dependent variable. In other words, their model asks, “what can the concentration of creative class workers in a city in 1994 tell us about what happens to employment in that city between 1994 and 2003?” By contrast, Florida et al.’s model asks, “what can the concentration of creative class workers in a city in 2000 tell us about wages in that city in 2000?” Set up this way, the model cannot even pretend to be predictive. And as a result, it becomes far less useful.

Furthermore, the theoretical model placing the “3T’s” at the center in this paper struck me as a little forced. The authors seem to bend over backwards to come up with reasons why Tolerance is a signifier for other things that may or may not contribute to prosperity. Witness, for example, this rather vague series of assertions:

Fourth, locations with larger artistic and gay populations signal underlying mechanisms that increase the productivity of entrepreneurial activity. Because of their status as historically marginalized groups, traditional economic institutions have been less open and receptive to bohemian and gay populations thus requiring them to mobilize resources independently and to form new organizations and firms. We thus suggest that regions where these groups have migrated and taken root reflect underlying mechanisms that are more attuned to mobilization of such resources, entrepreneurship and new firm formation.

When I see stuff like this I think, why not just measure the underlying mechanisms directly? If the point is that entrepreneurship and new firm formation is good economically, then why not include self-employment and new firms formed per year in the model? Instead, we have artists and gays as proxies for all of these other things. But here’s an important difference between the two: artists, by the very nature of their work, actually produce things that in themselves make neighborhoods more valuable — like live performances, gathering spaces, aesthetic markers, and so on. Can we make any such generalizations about gays, lovely people though they may be?

Concluding thoughts

The whole kerfuffle around which of human capital or creative class theory better predicts economic development, while providing much fodder for the blog, in the end amounts to little more than an academic pissing match. Both sides agree that the two measures are highly correlated and mostly capture the same people with some variation at the edges. The real question, in my opinion, is what draws these highly talented individuals with much to offer their communities to one place over another? To answer that question, Marlet and van Woerkens offer a simple model that performs markedly better than the 3T’s approach despite hewing closely to concepts embraced in The Rise of the Creative Class: namely, that highly educated, talented people value ready access to jobs, natural beauty, authenticity, and a lively street scene in their local environment. Florida et al.’s paper, on the other hand, still feels to me like a model in search of a justification; there is even a lengthy note on page 13 going into some detail about how many other regression techniques failed before they settled on the one used in the paper. It makes me wonder whether the 3T’s are more of a hindrance than a help in developing useful frameworks for these questions; taking a fresh look at the problem, as Marlet and van Woerkens did, may prove more fruitful in the long run. What I do appreciate about Florida et al.’s contribution is that it takes a step toward breaking out these complex interactions into their component parts; in other words, positioning talent concentrations as the result of numerous inputs with their own causal links, rather than the move-lever-A-get-result-B style of analysis we have seen in the past. Clearly, though, we still have a long way to go before we’ll have a complete understanding of the mechanisms behind regional development in the 21st century.