What is with the arts field’s obsession with the Got Milk? ad campaign? I feel like every time the subject of an ad campaign or slogan comes up, Got Milk is immediately referenced–it’s practically the Godwin’s Law of arts marketing. At NPAC, I apparently wasn’t the only one to groan when I learned that the most popular answer selected by attendees to the question “what should we do about arts advocacy and communicating our value at the national level” was the following: “Organize a national media campaign with celebrity spokespersons, catchy slogans (e.g. ‘Got Milk’), unified message, and compelling stories.” As Greg Sandow points out over at ArtsJournal:

[W]hat was missing from all of this was any discussion of the world in which these initiatives will have to be launched. And without that discussion, how can anybody know which of the many ideas presented are likely to work? Just imagine a commercial company making plans to promote a product. Wouldn’t they do market research? Wouldn’t they want to know what people think of the product, and what things about the product might (or might not) be appealing?

And yet here we have the arts — an endeavor that most people involved would think was far more important than a mere commercial marketing campaign — and all we bring to it is (forgive me) unfocused amateur enthusiasm. Organize a media campaign! Well, what’s it going to say? OK, fine, leave that to the professionals who’ll eventually run it. But if you yourself have no idea, how will you know whether the professionals will make sensible plans? (And, by the way, who’s going to pay for this campaign? It’s going to be expensive.)

Greg hits the nail on the head here, but it’s interesting to me that no one has asked an even more obvious question: did the “Got Milk?” campaign (or others like it) even work? Sure, it was witty and memorable and entered public consciousness and became parodied by everyone from Saturday Night Live to the New England Foundation for the Arts‘s Matchbook.org project, which asks on the front page, “Got Mariachi?” In a sense, as a work of art (as commercial ad campaigns go), it was very successful. But was it successful as a commercial ad campaign? Did it increase sales? Did it cause milk to be a greater, more meaningful part of people’s lives?

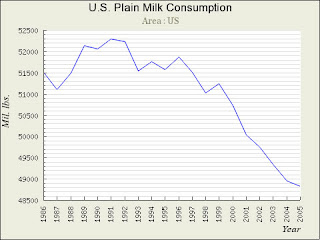

And the surprising answer is no! The Got Milk? campaign was introduced in October 1993. Consumption of plain (i.e., non-flavored whole, skim, and lowfat) milk in the US had been on a generally upward trend since 1987, peaking at 52.3 billion pounds in 1991. Yet during the heyday of the Got Milk? campaign in the mid-’90s, US plain milk consumption actually declined 2.3% from 52.2 billion pounds in 1992 to 51 billion in 1998, lower than in 1987! Worse, per capita plain milk consumption fell 6.7% during the same period. The Got Milk? campaign has continued running into the new millennium, and sales and consumption figures have only continued their decline, despite rising demand for flavored milk, cream, and yogurt. Now, obviously, it’s silly to conclude from this that one of the most successful ad campaigns in history is actually causing people to drink less milk. Rather, the lesson is that the societal forces and generational shifts that are causing people to drink less milk are too powerful for even the greatest ad campaign in the world to overcome.

And the surprising answer is no! The Got Milk? campaign was introduced in October 1993. Consumption of plain (i.e., non-flavored whole, skim, and lowfat) milk in the US had been on a generally upward trend since 1987, peaking at 52.3 billion pounds in 1991. Yet during the heyday of the Got Milk? campaign in the mid-’90s, US plain milk consumption actually declined 2.3% from 52.2 billion pounds in 1992 to 51 billion in 1998, lower than in 1987! Worse, per capita plain milk consumption fell 6.7% during the same period. The Got Milk? campaign has continued running into the new millennium, and sales and consumption figures have only continued their decline, despite rising demand for flavored milk, cream, and yogurt. Now, obviously, it’s silly to conclude from this that one of the most successful ad campaigns in history is actually causing people to drink less milk. Rather, the lesson is that the societal forces and generational shifts that are causing people to drink less milk are too powerful for even the greatest ad campaign in the world to overcome.

I hope we think about this the next time we’re tempted to look to marketing or advertising as the answer to all of our problems as a field. To be sure, an ad campaign can work wonders in the right context and under the right circumstances. But advertising history is littered with high-profile failures, too. Another suggestion from the NPAC final session was “Establish a National Arts Day/Festival with free performances, open houses, and art-making opportunities.” But really, how many national what-have-you days/weeks/months are there already that we never hear about? Did you know that November is Celebrating Philanthropy Month, for example?

Do we really want to roll the dice with the limited resources we have as a field, essentially playing double or nothing? Or do we want to invest those resources more wisely, by investigating small changes that make a big difference?