KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- Television is America’s national pastime. Adults spend an average of nearly three hours in front of the tube daily, outpacing the next most common leisure-time activity by a factor of four.

- There is surprisingly robust evidence suggesting TV watching may contribute to poor physical and cognitive health; when it comes to happiness and life satisfaction, however, the verdict is still out.

- Are people consciously choosing TV over other activities? There’s not a lot of evidence one way or another, but it doesn’t seem like most adults who watch large amounts of TV are doing so reluctantly.

- The arts are not the (obvious) antidote. People who attend exhibits and performances are no more likely to report being satisfied with their lives than those who don’t.

- We value adults’ freedom to make their own choices, so will need to see clearer evidence for an opportunity to improve wellbeing before committing to a case for change.

* * *

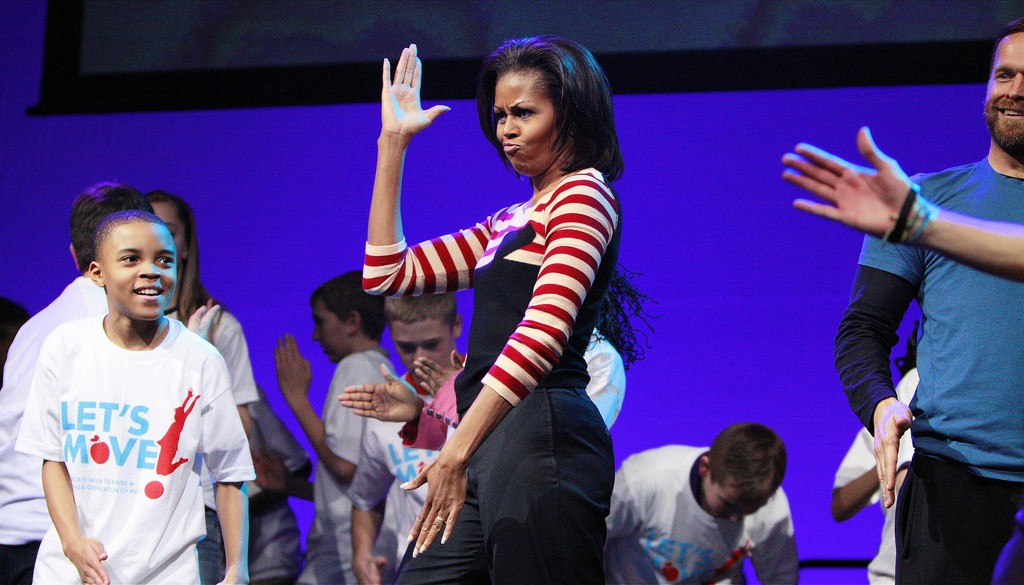

In 2014, First Lady Michelle Obama broke the internet with “Turnip for What,” a vine promo for her Let’s Move! campaign. She’s appeared on the Biggest Loser. She has her own viral dance sensation–the #GimmeFive, performed to Mark Ronson’s Uptown Funk. (You know it, right?) And she’s encouraging Americans to drink more water through fun social media stunts that appeal to our egos (hello, John Legend) and a line of chic accessories from the likes of J. Crew and Rebecca Minkoff. (Not to be outdone, POTUS and VPOTUS have been known to run around the White House and drink water, too.)

No, she’s not trying to be the next pop star. (Though we would totally buy her record.) She has a mission, and that’s to stem the obesity epidemic in the United States. The situation is, by all accounts, dire: 17% of children and almost 35% of adults are currently considered obese, and those numbers are worse among individuals with lower incomes and less education (so-called “low-SES” populations). Almost one in eleven adults has type 2 diabetes, and many more have prediabetes. Obesity is bad for our wallet: the US spends an estimated $147 billion in obesity-related healthcare expenses annually. It’s bad for the environment, too: cars are burning nearly a billion more gallons of gasoline a year than if passengers weighed what they did in 1960.

FLOTUS is but one character in the ongoing obesity saga. The Food and Drug Administration appeared in 2014 with new rules requiring establishments to post the calorie content of food on their menus. It went even further in 2015, when it required front-of-package labeling. Former Mayor Mike Bloomberg led a movement in New York to reduce soda consumption by limiting the sale of jumbo sugary drinks, which re-ignited the debate around the so-called sin tax. For more than a decade, public schools have battled youth junk food consumption with all sorts of methods: removing vending machines, imposing strict guidelines for school nutrition, and the Hail Mary move of banning birthday cupcakes.

The junk food hullabaloo raises interesting questions about choice, and whether individuals can or do make good choices for themselves. Here, the work of leading psychologists, economists and neuroscientists provides useful context: it is now widely accepted that most people make sense of the world by simplifying it, and the ways our brains are wired to simplify things can cause us to make judgments that are contrary to our best interests. There are a few reasons we might tend towards the simplify trap: hyperbolic discounting, which is our tendency to value immediate pleasure (or pain) over future consequences; loss aversion, or the fact that we dislike losing more than we like winning, which can make us risk-averse; or our tendency to focus only on what we know and what’s familiar. The combination of these factors makes low-risk, familiar propositions offering immediate satisfaction very hard to turn down. If we grew up with juice boxes and oreos as a school snack, and the closest grocer is a corner bodega stocked with chips and soda, and, well, sugar and salt and fat are so good, then of course we’d reach for cookies over carrots.

At this point, dear reader, you might be wondering why we have spent the first four paragraphs of an article about television and the arts talking about obesity. Well, as it turns out, TV (probably) makes you fat too.

TUNE IN, DROP OUT

Jamie K. is a 36-year-old from Fort Wayne, IN. She has a GED, and is unemployed. She likes to make jewelry and work on home improvement projects in her free time, which isn’t much, since she has three teenagers. She doesn’t go to arts events, because she doesn’t “have friends that are cultured, and it’s hard to go to things that [she] would find interesting by [herself].” She actively watches 10 hours of TV a day. Sonja B., a 57-year-old from Chicago, IL who is also unemployed, doesn’t attend arts events because they are usually in the evening, and she “wouldn’t want to go by [herself.]” She works out, and watches an average of 15 hours of TV, daily. Shantell T. is a 33-year-old administrative assistant from Washington DC. She watches 12 hours of TV on a typical day, and doesn’t consider herself to be a very “artsy” person.

In May of 2015, Createquity published Why Don’t They Come?, the first of many deep dives into the question of disparities of access to the benefits of the arts. The article looked closely at arts participation patterns among poor and less educated individuals, and considered obstacles to attendance including logistical reasons, such as cost and access to transportation or childcare, as well as other factors like feeling excluded and not having a friend to take along. (It is worth noting that many of the logistical reasons cited as obstacles to arts attendance are barriers to healthy eating as well. Cost and access in particular are blamed with the widening food gap between rich and poor.)

What we discovered in the course of our research surprised us. While the aforementioned obstacles were certainly barriers, a lack of explicit interest was far and away the dominant factor keeping low-SES populations away from arts events.

This is not to say that low-SES adults are not consuming cultural products. They are indeed consuming them in generous, perhaps even alarming, quantities–just in the form of television. Jamie, Sonja and Shantell are not alone: 93% of Americans spend time in front of the tube on a typical day, according to data from the 2012 General Social Survey (GSS). While almost everyone watches television, low-SES adults watch more than most. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ American Time Use Survey, individuals with less than a high school diploma spent 3.77 hours per weekday watching TV in 2013, almost double the TV hours consumed by those with a bachelor’s degree and higher. (Note 1) What’s more, these individuals spent twice as much time consuming television as on all other leisure activities combined, outpacing the next most common activity (socializing) by a factor of four. (You can dig into more such statistics here.)

Of all these statistics, one in particular stood out to us. Virtually alone among the activities we studied, television attracted more participation from poor and less educated adults rather than less. And on top of that, our analysis of GSS data suggested that even within low-SES groups, adults who don’t attend arts events watch even more TV than those who do. It seems possible that, whatever sustenance people are seeking from live arts attendance, the folks who don’t go are getting it (at least in part) from the small screen.

TV has a lot going for it: it’s easier than ever to watch what you want without paying for cable, and content is increasingly available on-demand, on devices you likely already own. No one will

Given the tendency to be distrustful of television, we were curious: are people going to be worse off on average watching TV instead of engaging in other, potentially more enriching, activities? Should this be an area of concern for our work here at Createquity? Is there an opportunity here to improve wellbeing through the arts?

SMALL SCREEN, BIG CONSEQUENCES

“It’s kind of a waste,” admits one of our interviewees. “I’m not really doing anything when I’m sitting and watching TV.”

As it turns out, sitting and not really doing anything when you’re watching TV doesn’t bode well for your physical wellbeing. There is compelling evidence that increased hours spent watching television is associated with obesity, in part because of the sedentary lifestyle it promotes by crowding out time that could be spent on exercise. SA Bowman looked at data from the USDA’s Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals (CSFII), and found that men and women across demographic groups, including race, income, and educational status, were more likely to be overweight as their average hours of television viewing per day increased. Women who watched more than two hours of TV per day were 41.4% more likely to be obese than women who watch less than one hour a day. For men, that figure was 90.29%. And it’s not just sitting that’s the problem: even among healthy Australian adults who exercise at least 2.5 hours per week, watching TV is straight up bad for the waistline, with more hours watching TV per day was associated with increased blood pressure, waistline, and cholesterol levels. (Note 2)

Research has indicated that TV affects physical health in other ways as well⏤even to the point of shortening your lifespan. One team’s analysis of the 2008 General Social Survey-National Death Index dataset reveals that each hour of TV watched per day is associated with a 4% increase in mortality risk, amounting to an overall reduction of 1.2 years in total life expectancy due to television viewing in the US. A 2010 paper found an increased likelihood of all causes of mortality with more than 2 hours of television watched per day. Yet a third paper finds that, compounding psychological factors aside, TV may lend itself to an increased likelihood of smoking (and we all know where the shoe drops there).

Spending significant time glued to the small screen is not just bad for your butt. It’s bad for your brain, too. Findings from a longitudinal study published in January 2016 suggest that watching television in early adulthood is linked with poor cognitive performance in midlife. As they aged, individuals with both low levels of physical activity and who watched three or more hours of television per day were increasingly likely to perform poorly on cognitive tests, even after taking demographic and health characteristics into account.

Are you doing some math in your head? (Your Favorite TV Shows x Total Viewing Hours) / Hours Watched Daily = Life Expectancy Reduction and Loss of Cognition? We did some math too, because there’s more to the brain than cognition. We ran a regression analysis on television and wellbeing using data from the 2012 General Social Survey. After controlling for variables including health, income level, education level, gender, age, and the frequency with which people interact with their friends and relatives, we found that increased hours of watching television is negatively associated with overall life satisfaction for people in the top three income quartiles, albeit only by a little bit. (Interestingly, we did not an association between television viewing and happiness for people with household incomes less than $25,000 per year). With a small sample and effect size and no ability to infer the direction of causality, we have to be careful not to push these results too far. Still, this descriptive analysis doesn’t do the case for TV any favors.

Others have investigated the relationship between watching a lot of television and one’s overall satisfaction with life (sometimes framed or referred to by scientists as subjective wellbeing). In their analysis of individual responses to the World Values Survey, which includes data from 80 countries, researchers Luigino Bruni and Luca Stanca found that television “crowds out” other, more social, activities–such as volunteering or spending time with friends and family–that are associated with higher life satisfaction. In the same study, they also suggest that increased hours spent watching television causes people to want higher incomes, which in turn creates unhappiness and low life satisfaction. According to Bruni and Stanca, TV is a part of a “relational treadmill” that induces people to measure their increase in happiness against that of their neighbors, instead of against their own experiences. Television, they argue, makes people want to consume more, inspired by both advertising and program content; unfortunately, by this metric, individuals will never achieve a real increase in happiness that corresponds to their increase in buying power. Some take issue with the way Bruni and Stanca classified countries in their methodology (see here), and at least one set of researchers note that when considering heterogeneity within countries, people who watch television report higher levels of wellbeing than people who do not watch any television at all. Still, we likely can all point to an example of being sucked into the “relational treadmill” of consumption thanks to TV.

It’s not just the quantity but also the quality and type of programming that may be bad for subjective wellbeing. There is a significant body of research on whether and how viewers are directly affected by what they watch on television, and how that may inform the way that they think about the world. Studies show that television can be associated with shaping political contests, purchasing behavior, or increases in aggression or fear of being victimized. In an investigation of how local news influences perceptions of the likelihood of high-risk events, one study across three different datasets found that people who watched local news frequently were more likely to think that they were at risk of criminal victimization than people who watched less local news. According to media and communications professor Sonia Livingstone, television has a profound effect on the way that we perceive our everyday lives. She argues that the idea that people passively consume television without trying to make meaning of its contents is false, and that most viewers make deep connections to on-screen characters and stories that impact their daily realities. In her book Making Sense of Television, she draws on the literature of audience interpretation, psychology, and literary criticism to discuss how audience members form parasocial relationships with characters on the small screen. Given the prevalence of television in our lives, she notes that “psychologically it does not seem plausible that our assumptions, images, and knowledge of the world portrayed by television can be strictly separated from our assumptions, images, and knowledge of everyday life.”

THE TWIST

You would think with all this talk of obesity, mortality, and dissatisfaction with life, people would reach for the off button. The fact that they don’t suggests they must be getting something out of it.

Could it just be that people who watch large amounts of TV lack self-control? That could explain some of these findings; for example, there is research that indicates unhappy people in general tend to watch more TV, suggesting that depression might be the culprit in some cases. But that doesn’t seem to be the whole story. There is an emerging body of research on television and addiction, but people are still trying to understand it, how many people are affected, and how it relates to other addictions that might be more disruptive to daily life. We have not found evidence tying television addiction to income level, even though people with lower incomes tend to watch more TV.

The statistics in general do a great job of making TV sound horrible, but spend some time actually talking to people about why they watch, and you may find your viewpoint shifting. Frances T. of Oahu, HI is 38 and completed some college. She watches at least five hours of television a day, even though the rest of her family’s in bed by 9pm. For her, TV is informative and keeps her tapped into what’s happening locally and nationally. It also helps expand her opinion on different topics, which she values. Sonja B. agrees: “I like shows that add something to my everyday life,” she notes, adding that she prefers judge shows because she finds them educational, and talk shows because they expose her to information she might not otherwise come across. Jamie K. likes watching documentaries because she feels like she is learning something. Charisse P., 38, works with in-patient youth in a psychiatric facility in Birmingham, AL. She watches five or six hours of TV a day, and finds it a good coping mechanism: “if I’m having a bad day and a funny show is on, the laughter helps, it helps a lot.”

Then there’s the fact that, for many, watching television is a meaningful social experience. Kawanda C. lives in New Orleans, where she doesn’t have a car. She’s 31 and didn’t finish high school. She works as a cashier, and spends a lot of time getting to and from work. She watches on average eight hours of TV a day, and loves to watch with her kids. Sonja B. also opts for companionship when taking in her favorite shows: “It’s always fun to watch TV with someone else because they might have a different perspective.” Indeed, in contrast to to Bruni and Stanca’s findings about television crowding out social activity, researcher Nele Simons’s interviews with TV watchers show that they socialize around the television they watch. She even suggests that people watching television at different times can create new opportunities for TV and socializing. In Simons’s telling, the classic mid-century meme of a traditional family unit gathered around to watch I Love Lucy or the Ed Sullivan Show continues, only today it’s football at your uncle’s place, or Game of Thrones at your corner dive bar.

Family watching television. Evert F. Baumgardner, ca. 1958 – from the National Archives and Records Administration.

It does seem that qualitative methodologies tend to paint a more positive picture of the effects of television. A set of interviews with Dutch adults aged 65-92 published last year explored the question of whether their television viewing habits are more often part of a selection strategy–that is, a conscious choice made to maximize wellbeing–or a compensation strategy, a choice that is made to fill time or otherwise compensate for some kind of loss or diminishment. While there were certainly examples of compensation strategies among their interviewees, the researchers more often found that people were watching TV with no regrets.

But the TV-is-good-for-you case is more than anecdotal; there’s a small but growing body of quantitative research that paints a more positive side to the medium as well. Recall that our aforementioned analysis of the General Social Survey found that among the lowest income quartile, which is also the segment that watches the most TV, more television is not associated with lower life satisfaction. One hypothesis to explain this comes from a paper by Bruno S. Frey et al. analyzing data from the European Social Survey. Frey et al. found that people with a lower opportunity cost of free time, like unemployed people or those with very fixed working hours, were less likely to report decreased life satisfaction as their TV hours increase, while the opposite was true of individuals with a high opportunity cost of their free time. If people with lower incomes tend to have a lower opportunity cost of their free time, this might explain why television at the bottom income quartile does not seem to harm life satisfaction.

While we haven’t encountered research showing positive effects of television content on adult viewers, there are some success stories for children and teens. In one study, researchers Kearney and Levine looked at the MTV franchise 16 and Pregnant–a series of reality TV shows including the Teen Mom sequels–and determined that the shows ultimately led to a 5.7% reduction in teen births in the 18 months following their introduction, which is about one third of the reduction in teen births during that period. In a follow-up, Kearney and Levine found that preschoolers who lived in areas where they could watch Sesame Street were 14% less likely to fall behind when they got to elementary school, and that this effect was much more pronounced for kids who grew up in areas with higher levels of economic disadvantage.

I WILL CHOOSE FREE WILL?

TV makes us fat. It dumbs us down. Too much TV makes us unhappy. Not enough TV makes us unhappy. TV makes us laugh. It keeps us informed. It keeps us from more social activities. It’s an opportunity for family time. It’s dangerous: for our feeling of self worth, for our capacity to understand right from wrong. At the end of the day, there’s plenty of evidence to suggest that TV is both good and bad for us, depending on who we are, how we define good and bad, and how we go about asking and answering the question.

To be sure, not all of this evidence is created equal. If we were to pit the “TV is good” and “TV is bad” hypotheses against each other in a contest of methodologies, bad would probably win out. But how bad is bad? What exactly is the threshold of evidence of harm that would warrant taking the position that TV requires an intervention?

Here, the case of junk food provides us with a useful comparison. The impact of junk food consumption on public health has generated enough concern among reasonably-minded policy wonks to motivate multiple attempts at intervention by the state. And yet even for junk food, that movement to change behaviors has not come without controversy. The FDA, under intense pressure from Congress (and the National Restaurant Association) was forced to delay nation-wide implementation of menu labeling requirements until after the upcoming Presidential elections. (NYC implemented these same rules in 2006, and it took a full two years for them to become reality.) This past November, NYC passed a law requiring restaurants to indicate highly salted dishes; it was challenged immediately. Bloomberg’s famous soda ban was struck down, suffering from a backlash from the very people it was intended to help. Richmond, CA took a different approach, introducing a soda tax rather than a size limit, but it, too, failed.

What’s more, many of these well-meaning attempts to regulate the health of Americans don’t seem to be working: menu labeling has not been shown to change eating habits (and at least one study suggests it leads to greater caloric intake.) Kids denied in-school vending machines often end up consuming extra junk food. One year after Berkeley, CA became the first city in the US to successfully pass a soda tax, a study of its effectiveness reveals that, as the price increase has been largely assumed by distributors, the intended effect on consumers is negligible.

So to return to our initial question: are people going to be worse off on average watching TV instead of engaging in other, potentially more enriching, activities–like attending arts events? It’s hard to draw a definitive conclusion from the evidence, but in a way, that is its own conclusion. Much as we might like to believe otherwise, the arts are not some magical happiness-generating machine: our analysis of responses to the 2012 General Social Survey shows that people who attend arts exhibits and performances are no more likely to be satisfied with their lives than those who don’t, after controlling for demographic and baseline characteristics. Meanwhile, TV can provide many of the aesthetic pleasures that arts events are supposed to provide, usually at lower cost and with greater convenience. For Leslie B., a 40 year-old from Washington DC. who watches 15 hours of TV daily, anime is the top. She’s a photographer and wardrobe stylist, and takes inspiration from the way the characters are drawn. Charisse P. emphasizes the need for shows to have good storylines and strong characters. She’s drawn to programs with lots of surprises. Shantell T. likes shows with good music, like Empire.

While there are certainly aspects of the effect of TV on physical, cognitive and subjective wellbeing that are concerning and deserve further exploration, given how dicey it is to seek to intervene in adults’ choices, our instinct is to exercise caution. For us to move forward in pursuing a case for change with respect to TV, we would need to see clearer evidence for an opportunity to improve wellbeing.

For us, the question of wellbeing ultimately comes down to opportunity and choice. Our definition of a healthy arts ecosystem draws inspiration from the “capability approach,” a widely adopted philosophical framework developed by Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum that defines wellbeing in terms of freedoms. According to the capability approach, whether or not people take advantage of the opportunities they have, their capability to make decisions about how they pursue their lives is vital to wellbeing, and having the capability to achieve various states is more important than whether or not one chooses to exercise that capability.

Frances T. talks about the impact of TV on her life

It seems like a whole lot of people are making the choice to reach for the remote. For some, this undoubtedly isn’t the best choice they could make. For others, maybe it is. And it’s really hard for us, or anyone else, to tell the difference. Tempting as it might be to judge people who spend eight hours a day in front of the TV, many of us spend that much time or more each day in front of a different sort of small screen. We can only hope that everyone who does so is as enthusiastic about it as Frances T., who confidently declared when we asked her whether TV affects her wellbeing, “it is my own wellbeing to watch TV.”

Liked this article? Two things. First, we’ll be hosting a #CreatequityAsks Twitter chat to discuss the implications of this work on Wednesday, March 9 from 4-5pm Eastern time. Second, we’re conducting a reader poll to help us determine what we should investigate next. Please take 5 minutes to share your opinions! Thanks so much.