SUMMARY:

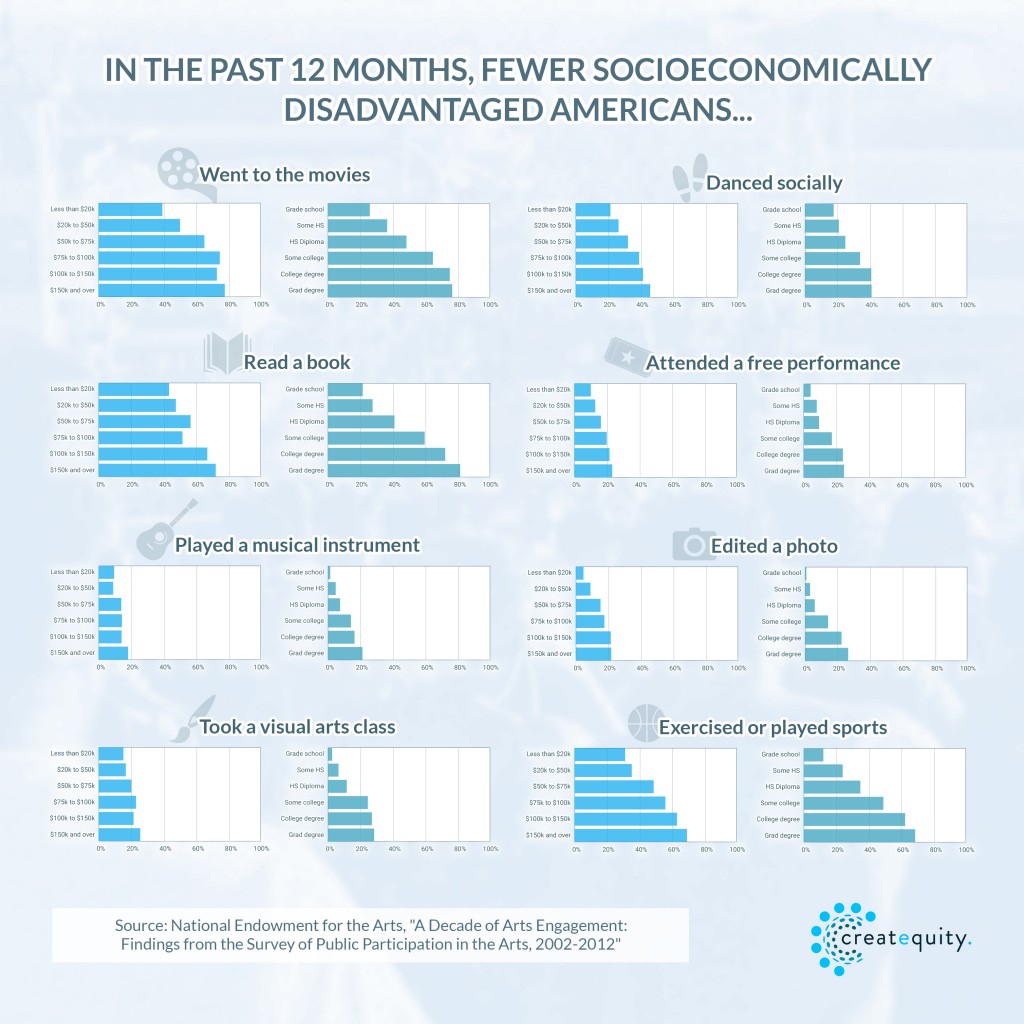

- People with lower incomes and less education (low-SES) participate at lower rates in a huge range of activities, including not just classical music concerts and plays, but also less “elitist” forms of engagement like going to the movies, dancing socially, and even attending sporting events.

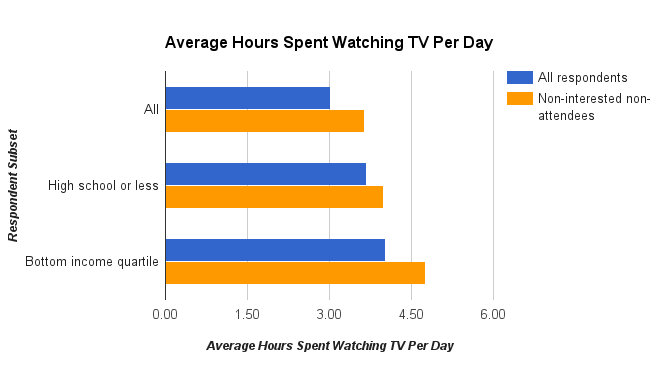

- This is despite the fact that low-SES adults actually have more free time at their disposal, on average.

- Cost is a barrier for some low-SES individuals who want to participate in the arts, but not as many as you might think. If we could somehow make it so that low-SES adults were no more likely to decide not to attend an exhibit or performance because of cost than their more affluent peers, it would hardly change the socioeconomic composition of audiences at all.

- A major contrast to this dynamic is television. Ironically, the for-profit commercial TV industry is far more effective than our subsidized nonprofit arts organizations at engaging economically vulnerable members of our society. Not only do low-SES adults watch more TV, low-SES adults who don’t attend arts events watch even more TV than low-SES adults who do.

- Where to go from here? We’d like to better understand why people make the choices they do before offering recommendations. At the very least, though, we can say that television should receive far more recognition than it does for its role in shaping the cultural lives of socioeconomically disadvantaged adults.

* * *

On March 18, the Empire finale aired on Fox. The two-hour episode was seen – on TV, in real time – by more than 17 million viewers nationwide. An estimated 50% of all African American households tuned in. In February, the New York City Ballet sold out its 2,500 seat house for three “Art Series” performances, as is typical of this series. (Each ticket, regardless of location, was priced at $29.) Last July, bachata star Romeo Santos sold out two nights at Yankee Stadium, performing for more than 100,000 people. (Two thirds of the tickets cost more than $100.) During the 2013-14 season, the Metropolitan Opera transmitted ten operas via satellite into some 2,000 theaters in 66 countries, including more than 800 in the U.S. Box office numbers hit $60 million worldwide. (Average ticket prices were $23.) Last summer, some 90,000 people put at least $300 and four full days (to say nothing of accommodation costs and travel time) towards attending Bonnaroo, the Tennessee rock/pop music festival. More than half of those attending came from farther afield than “the south.”

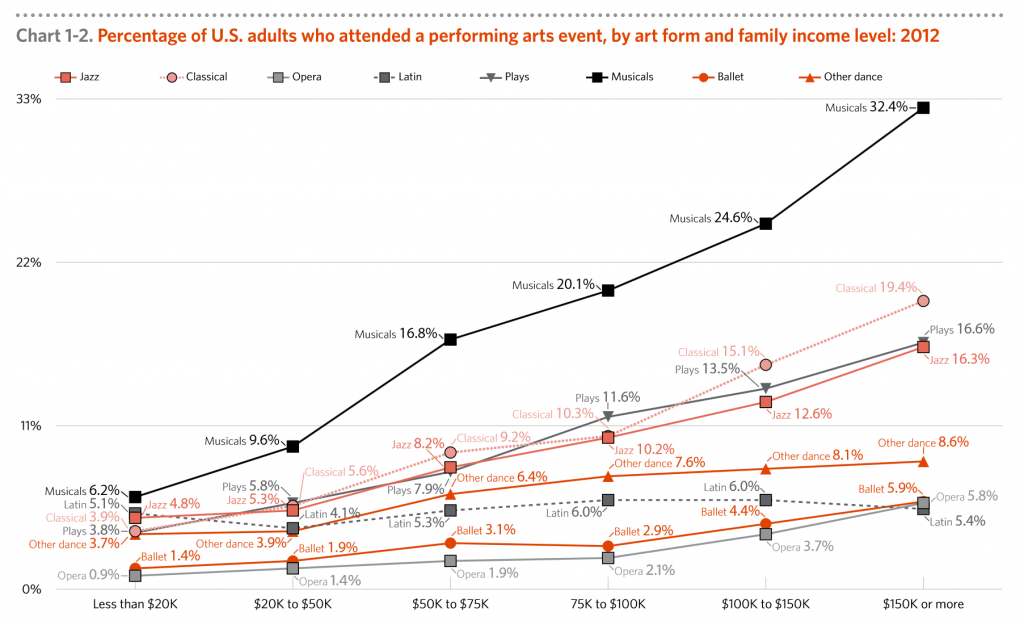

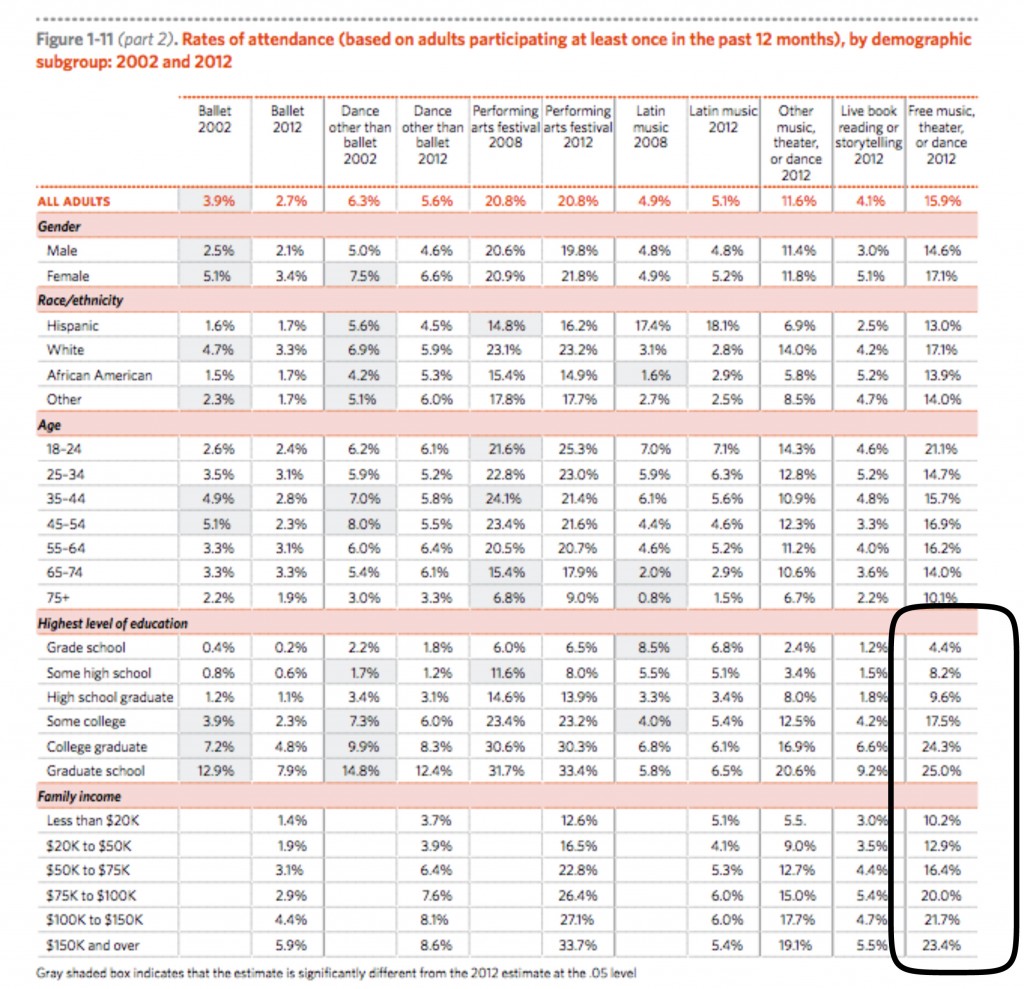

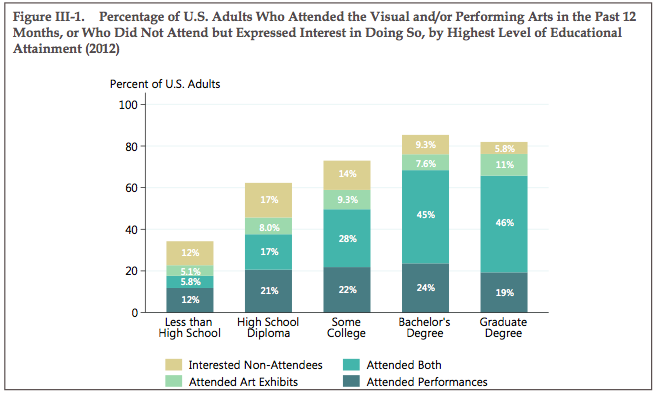

With statistics like these, it’s hard not to come away with the impression that “the arts” – from ballet to Bonnaroo – are alive and kicking, well-attended and avidly consumed by every demographic imaginable. A closer look at the data, however, surfaces evidence that individuals of low socioeconomic status (“low-SES”) – generally defined in our reading as those with at most a high school education and in the bottom half of the income distribution in the United States – consume the arts at a much lower rate than their more affluent counterparts. The latest Survey of Public Participation in the Arts (SPPA) in the United States shows that in 2012, probability of arts attendance tracked closely with level of formal education: college graduates were more than two and a half times as likely to attend a so-called “benchmark” arts event in 2012 as those with no more than a high school education. Looking at income levels shows a similar correlative relationship: those earning between $20,000 and $50,000, who make up one-third of the US population, made up just a quarter of 2012 benchmark arts audiences in 2012. Statistics from the UK, Ireland, and the Netherlands tell a similar story.

Source: National Endowment for the Arts, “A Decade of Arts Engagement: Findings from the Survey of Public Participation in the Arts, 2002-2012.”

Historically, research into the demographics of arts consumption has used a rather narrow lens to define “the arts.” The NEA’s benchmark arts activities, which have been measured in every edition of the survey since 1982, include only live attendance at ballet, opera, musical and nonmusical plays, classical music, jazz, museums, and galleries. However, the most recent edition of the SPPA makes clear that it’s not just benchmark activities that are at issue. Data from the survey shows that fewer low-income individuals attend pop and rock concerts than their wealthier counterparts, and significantly fewer of them attend visual arts festivals and craft fairs. In fact, people with lower incomes and less education are less likely to read books, go to the movies, take an arts class, play a musical instrument, sing, dance socially, take or edit photographs, paint, make scrapbooks, engage in creative writing, or make crafts.

All told, the data paints a consistent portrait of lower participation by low-SES adults in a breathtaking range of visual, performing, literary, and film activities. While this definition of “arts” doesn’t include everything (more on this later), it is broad enough, and the differences of sufficient magnitude, to be cause for significant concern. If those differences reflect disparities of access to more “common” arts experiences like participating regularly as an audience member, they represent a significant challenge to Createquity’s conception of a healthy arts ecosystem. When large numbers of people face barriers to participating in the arts in the way they might want to, we know that we’re missing opportunities to improve people’s lives in concrete and meaningful ways. What’s really behind this phenomenon of lower participation rates among economically disadvantaged people? And what can, and should, we do about it?

THE PRICE IS TOO DAMN HIGH (OR IS IT?)

Earlier this year, the National Endowment for the Arts published “When Going Gets Tough,” a report that for the first time offers extensive insight into the reasons why people do or do not attend arts events. Drawing from a special cultural participation module within the 2012 General Social Survey (GSS), the survey asked respondents whether they had attended an exhibit or performance in the past year, and if not, why not. More than half of respondents had indeed attended at least one exhibit or performance during that time, and another 13% shared that they had wanted to go but decided not to for whatever reason. The report refers to this latter group as “interested non-attendees.”

The most common factor keeping people away from arts experiences, cited by nearly half of interested non-attendees, was that they “could not find the time.” This makes sense: before ponying up for a three-day festival in Tennessee or a five-hour opera, we first have to decide if we can afford the hours.

But while lack of time is undoubtedly an obstacle for many, it does not disproportionately affect lower-income and working class respondents. “When Going Gets Tough” notes that “not being able to find the time, including due to work conflicts, is increasingly mentioned…at higher incomes. [Only] 31% of those in the lowest income quartile mention time constraints, compared with 53% of those in higher income quartiles.” While perhaps surprising, this finding is not isolated to the arts: the phenomenon of less perceived time at higher incomes is well documented in the literature. According to Daniel Hamermesh and Jungmin Lee’s analysis of time use datasets from several countries for their cheekily-titled study “Stressed out on Four Continents: Time Crunch or Yuppie Kvetch?,” “complaints about insufficient time come disproportionately from well-off families.”

Is this just a matter of perception? Do low-SES individuals feel less time-poor only because time pales in importance to other barriers they face? In fact, the preponderance of evidence suggests that low-SES people really do have more time at their disposal on average. According to a longitudinal study of time-use data by Almudena Sevilla, Jose I. Gimenez-Nadal, and Jonathan Gershuny, discretionary time has increased for all Americans over the last fifty years, and while hours of leisure time were once fairly equal across education levels, low-SES people have since enjoyed dramatic gains. By their estimation, low-SES men with at most a high school education have gained an hour more than their college-educated peers during that time; the corresponding differential for women is 3.4 hours.

Bottom line: all signs point to low-SES people having relatively more free time at their disposal and lower rates of arts attendance than their high-SES counterparts. That would seem to offer pretty strong evidence against the notion that time constraints are the primary factor keeping this demographic away from live performances and exhibits.

* * *

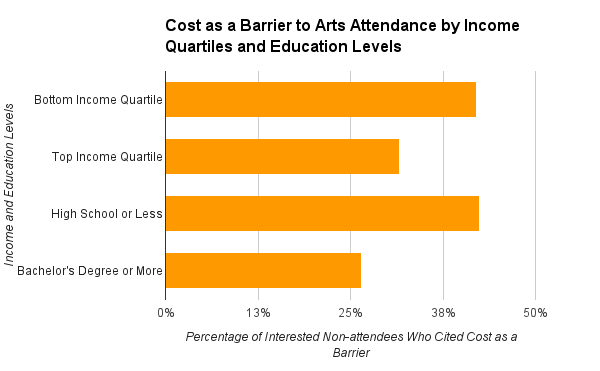

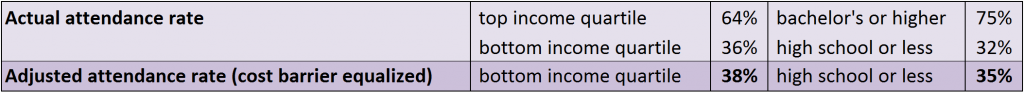

What about cost? For decades, our field has offered free concerts, outreach programs, and other engagement efforts that all rest on an assumption that the price of admission is a barrier to arts consumption for low-SES individuals. Taken literally, that assumption is supported by data from “When Going Gets Tough,” which indicates that cost was a barrier for nearly 40% of interested non-attendees. While the report itself does not go into detail on the extent to which cost is felt as a barrier across income strata, our own analysis of the underlying survey data indicates that low-SES individuals are indeed more likely to mention cost. Among interested non-attendees, 43% of people in the lowest income quartile were not able to attend an exhibit or performance because of cost, compared to 30% of folks in the highest quartile. Viewed through the lens of education, the difference is even more dramatic: those who had progressed no further than high school were almost twice as likely to see cost as an obstacle than respondents with a bachelor’s degree.

Looking at the motivations of people who did attend arts events, we see a similar dynamic. Adults in the lowest quartile of household income were twice as likely as those in the highest quartile to indicate that low cost or free admission was critical to their decision to attend an event. Even at events that were free for everyone, 29% of low-SES attendees said that low (or no) cost was a major reason for their attendance, versus 17% of those in the top income quartile.

So the way to get everyone participating in the arts is to invest more in free events and outreach programs to underserved populations, right? Not so fast. While it is clear that cost does affect the ability of some low-SES adults to engage with the arts, or at least live exhibits and performances, it’s not at all clear that removing cost as a barrier would make that much of a difference.

Consider this: “When Going Gets Tough” reports that there is only a 6 percentage-point gap between the lowest and highest income quartile for those who had free admission to the most recent arts exhibit they’d attended (64% in the lowest income quartile vs. 58% in the highest income quartile). While the difference in attendance at free performances is more pronounced in the GSS data, the most recent SPPA survey tells a different story: the rate of arts attendance at free music, theater, or dance performances actually increases as income and education levels go up. Moreover, this phenomenon has been observed in arts research going back at least half a century. For their seminal early 1960s investigation of cultural economics, Performing Arts: The Economic Dilemma, William J. Baumol and William G. Bowen surveyed more than 30,000 attendees at 160 events in the US and UK and found that not a single free performance was able to draw an audience that was more than 10% “blue-collar.”

Source: National Endowment for the Arts, “A Decade of Arts Engagement: Findings from the Survey of Public Participation in the Arts, 2002-2012.”

Admittedly, we don’t know the whole story here. Perhaps affluent adults are more likely to hear about free events, or have relationships with people who can get them free tickets. And even “free” is not necessarily free, if it still costs money to get to the location or pay for child care. Whatever the reasons, though, the data suggests that simply offering a free option is not sufficient for arts institutions to ensure a socioeconomically representative audience. In our own analysis of the survey data from which “When Going Gets Tough” was sourced, we modeled a scenario in which low-SES people were no more likely to face cost as a barrier in attending an exhibit or performance than their high-SES counterparts. Roughly speaking, this simulates what would happen if every exhibit and performance in existence could be attended for free. The result? Only 7% of the chasm in attendance rates between rich and poor, and between college-educated and not, would be bridged.

Source: 2012 General Social Survey via ICPSR National Archive of Data on Arts and Culture, author analysis

“When Going Gets Tough” does find one other barrier to access that’s correlated with income: ease of getting to the venue. According to the report, “44 percent of adults in the lowest income quartile said the exhibit or performance was too difficult to get to….In contrast, only 24 percent of those in the highest income quartile mentioned this issue.” Yet, like cost, this factor on its own is not enough to explain the disparity. Indeed, according to our model, even if all barriers to participation were removed for low-SES populations and every person who wanted to attend an exhibit or performance in the past year were able to do so, it would still not close even half of the gap in attendance rates.

Source: 2012 General Social Survey via ICPSR National Archive of Data on Arts and Culture, author analysis

Clearly, there is something else going on. If none of these barriers fully explain the low participation rates among the socioeconomically disadvantaged, what else is keeping them away?

ARTS VS. THE TUBE (MIND THE GAP)

Createquity’s definition of a healthy arts ecosystem imagines a world in which “each human being today and in the future has an opportunity to participate in the arts at a level appropriate to his/her interest and skill” (emphasis added). Our concern about disparities of access to the arts stems from the potential for life circumstances to interfere with such choices. The revelations in this research, however, suggest that there is a significant proportion of economically disadvantaged people who do not take the initiative to experience the arts, even when time and cost are not issues.

Source: National Endowment for the Arts, “When Going Gets Tough”

Our analysis of the GSS data underlying “When Going Gets Tough” shows that a lack of explicit interest is far and away the dominant factor keeping low-SES populations away from arts events. Just under a third of the overall sample neither attended an exhibit or performance in the past year nor could recall one they wanted to attend but couldn’t. Among the bottom income quartile, however, this number was nearly half – and for people who hadn’t finished high school, it was over 65%!

Amid the litany of arts-related activities for which participation correlates with increased income and higher education, one notable exception looms large. Aside from eating, television is about as close to a universal American pastime as exists today. A whopping 93% of us spend time in front of the tube on a typical day, according to the GSS, and nearly 97% of American households own a TV set. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’s American Time Use Survey (ATUS), watching TV was the leisure activity that occupied the most time (2.8 hours per day) in 2013, accounting for more than half of leisure time for those age 15 and over. John P. Robinson and Geoffrey Godbey in “Busyness as Usual” show that television consumption has increased dramatically in recent decades across all populations, noting that TV has eaten up six of the eight hours of the discretionary hours we’ve gained on average since 1965.

While almost everyone watches television, it turns out that low-SES people watch more than most. A closer look at the Time Use Survey numbers shows that individuals with less than a high school diploma spent 3.77 hours per weekday watching TV in 2013, almost double the TV hours consumed by those with a bachelor’s degree and higher. What’s more, these less-educated individuals spent twice as much time consuming television as on all other leisure activities combined–including reading, socializing and communicating, sports and exercise, relaxing, and playing computer games.

A similar dynamic can be observed in the spending patterns captured in the BLS’s Consumer Expenditure Survey. Although individuals in the top income quintile spend only a little bit more of their budgets on “entertainment” on the whole than those on the bottom (5% vs. 4%), the distribution within this amount is quite different. In the lowest income quintile, more than half of spending goes to “audio and visual equipment and services” (which presumably includes TVs), while just over a tenth goes to “fees and admissions.” The top bracket, by contrast, spends more on fees and admissions than on A/V equipment and services.

It seems likely that quite a few low-SES adults are essentially substituting television for other forms of engagement with the arts and entertainment. Our analysis of GSS data offers strong evidence to support this hypothesis. It turns out that even within low-SES groups, a lack of expressed interest in attending an exhibit or performance over the past year correlates with more hours spent watching TV. Whatever sustenance people are seeking from live arts attendance, it seems the folks who don’t go are getting it (at least in part) from the small screen.

Is that something to be worried about? At least one group of researchers argues that it is. In their previously-mentioned study on leisure inequality, Sevilla et al. find that in contrast to previously mentioned increases in the quantity of leisure time, the quality of leisure time has declined across the board for people at all income levels, with an especially steep decline in leisure quality for low-SES individuals. In other words, even though low-SES individuals have experienced the greatest increase in number of discretionary hours since 1965, they have also experienced the greatest decline in the “quality” of how those hours are spent, as measured by their relative levels of different types of leisure. Sevilla et al. see increased TV watching as a prime culprit behind this decrease in leisure time quality, as watching TV is a passive, one-way communication medium that doesn’t require the presence of others.

On the other hand, TV is relatively cheap for the quantity of programming available and can be delivered on demand via devices we likely already own. And in the midst of what many are calling a new golden age of television, claims on the part of egghead researchers about “low-quality” leisure time might ring hollow to the folks who tune in every day.

(MAYBE) THEY’RE JUST NOT THAT INTO YOU

The truth is that we don’t know much about why low-SES people make the choices they do about how to spend their free time. Are they watching television because they truly enjoy it and happen to find it more fulfilling than going out to a concert, a museum, or a movie theater? Or are they doing so as a reluctant concession to circumstance, with TV being the only art form they can afford to consume (or the only one they don’t have to schedule in advance)? Or perhaps something in between – a “learned” and socially reinforced preference that has as much to do with identity as anything specific to the experience itself?

“When Going Gets Tough” offers some support for the last of these propositions. Survey respondents who self-identified as middle or upper class were much more likely to attend an exhibit or performance than those who identified as working class. This finding held even after controlling for income and education:

For example, among individuals whose household income was around the national median, approximately 60% identified as working class and 36% as middle class. Despite having very similar household incomes, only 48% of those identifying as working class attended at least one exhibit or performance, compared with 67% who identified as middle class.

Perhaps some low-SES individuals don’t attend arts events simply because they don’t think of themselves as the “kind of people” who attend arts events. Which brings us back to the question: is that a problem?

We would urge would-be social engineers to tread carefully when it comes to deciding for poor people what their consumption preferences should be. (An instructive example here is the movement in New York City and elsewhere to reduce soda consumption, which has faced pushback from the very low-income communities it’s intended to help.) How far can one go to increase participation by underrepresented audiences before those efforts stop being perceived as generous and start coming off as patronizing? Until we know more about low-SES people’s subjective experience of their free time — whether they would spend their time differently if they had the opportunity, and whether there’s a place for the arts in those dreams — we advise against making too many assumptions.

There is a rich irony lurking just beneath the surface here: television, a largely for-profit commercial industry, routinely does a much better job engaging the most economically vulnerable members of our population than our supposedly charitable nonprofit arts institutions that receive tens of billions of dollars annually in government-sanctioned subsidy. As TV becomes increasingly untethered from broadcast networks and big cable channels and increasingly experienced on laptops and handheld devices, the nonprofit arts sector would do well to let go of its historical marginalization of the small screen. For better or worse, television is a powerful cultural force, and ignoring it is no longer tenable in an era of increased attention to cultural equity and community relevance.

BACK TO OUR REGULARLY SCHEDULED PROGRAMMING

In the meantime, however, let’s not forget that we have identified one constituency that is clearly suffering under the status quo. More than 45% of low-SES adults who were interested in participating in an exhibit or performance over a 12-month period did not do so because of cost – a figure that is more than 10 percentage points higher than their high-SES counterparts. According to our analysis of the GSS data, roughly 1-1.5 million people in the United States over the age of 18 fall into this gap. Not only does cost of attendance matter more for low-SES individuals and families with less discretionary income, with income inequality in the United States exploding, the number of people who face economic barriers to their desired level of participation in the arts is likely to multiply if current trends continue. And remember that these numbers apply only to exhibits and performances, but there are lower rates of participation by low-income and less-educated adults in numerous other activities as well, including going to the movies and many types of art-making and arts learning. The SPPA even reports that the same education and income correlations we’ve been talking about apply when it comes to attending a sporting event, playing sports, and physical exercise. It’s likely that cost limits the ability of low-income and less-educated individuals to participate in all of these to some extent.

While it’s not surprising to see lower participation by socioeconomically disadvantaged adults in arts activities that they perceive as too expensive, it’s important to keep that gap in perspective. Our investigation has uncovered evidence that although this problem is real, it directly impacts the choices of a much smaller number of people than we might have guessed. As we continue our core research process at Createquity, we’ll be looking to understand better why poor people and those who have not attended college seem much less likely to even be interested in participating in the arts, as well as weigh this particular disparity of access alongside others that we have yet to examine closely or even identify. We look forward to sharing what we find.