Arts organizations and community stakeholders create and commission public art with many good intentions with respect to its audiences. Historians and practitioners alike seem to agree that much could be gained from understanding what people are noticing, thinking about, and doing with public art. In the words of public art historian Harriet Senie, “since part of the raison d’être of public art is an expanded audience, it is essential that responsible criticism consider reception.” In other words, if public art is designed for a broad public, then we need to know how that public is actually reacting to it.

As I described in my January 2012 article “Public Art and the Challenge of Evaluation,” however, gathering reliable data on a public artwork’s impact at the audience and neighborhood level is difficult. When I first started researching this topic as a graduate student in 2007, interviews with leaders in the field indicated that little was being done to document how many people experience a work of public art, or their responses to it. Similarly, little effort was put toward providing interpretive materials that might enhance visitor understanding or participation. Such endeavors were seen as too costly and complex for most organizations.

Today, just six years later, web and mobile technologies offer new learning opportunities for organizations and audiences alike. Myriad interactive public art websites, social media platforms, podcasts, mobile audio tours, and smartphone apps allow people to easily find, learn about, and interact with public artworks. These tools bring comprehensive images and information literally to users’ fingertips. Can they also provide valuable information on public art’s audience, telling a broader story about public art’s community impact? Can they help us evaluate as well as promote and explain public art?

Through interviews with public art organizations innovating with interactive technology, close analysis of several organizations’ social media pages and online photo albums, and my own experience curating the FIGMENT sculpture garden, I discovered that it is difficult to evaluate the impact of public art itself on audiences apart from the impact of the engagement tools. Yet while not a substitute for more formal research techniques like audience surveys, these tools can play an important role in the evaluation process if used to their fullest potential.

How and why is interactive technology currently used to engage people with public art?

Information-sharing online

Increasingly sophisticated public art websites help people virtually experience public art. Most public art administrators seem to agree that documenting and sharing completed public art online is important to generate interest and funding for new programs, and to enhance public art tourism and appreciation in a region. Over 80% of respondents to a 2012 survey and focus group conducted by the Western States Arts Federation (WESTAF)’s Public Art Archive (PAA), reaching 60 public art collections nationwide, reported that they have put at least part of their public art collections online, or plan to do so in the future.

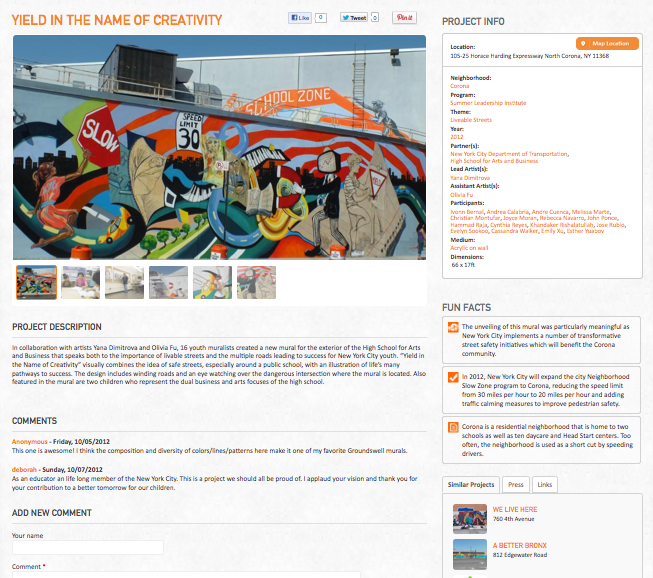

![PAA example Screen shot of a sample collection from PAA. PAA’s mission is “to provide a sophisticated, free, online, searchable [web and mobile] database of public art in the United States and Canada.” PAA puts all types of public art collections online and now hosts works from over 250 collections across the U.S and Canada.](https://createquity.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/PAA-example1.png)

Screen shot of a sample collection from PAA. PAA’s mission is “to provide a sophisticated, free, online, searchable [web and mobile] database of public art in the United States and Canada.” PAA puts all types of public art collections online and now hosts works from over 250 collections across the U.S and Canada.

Web technologies also allow public art organizations, like museums, to set up online “curated” public art tours; close-up explorations of specific artworks; lesson plans (as seen on the New York City Public Art for Public Schools “teacher” section and an increasing number of other public art sites); and interactive quizzes and activities, each with robust audio and video components.

Philadelphia’s Mural Arts Program (MAP)’s website has online mural tours organized by themes like food, social justice, or black history. MAP’s site exemplifies the trend of, in the words of Philadelphia’s Association for Public Art (aPA) director Penny Balkin Bach, having “authentic voices… people from all walks of life who are personally connected to the [public art].” aPA and MAP both offer downloadable public art tours narrated by artists, curators, civic leaders and community members.

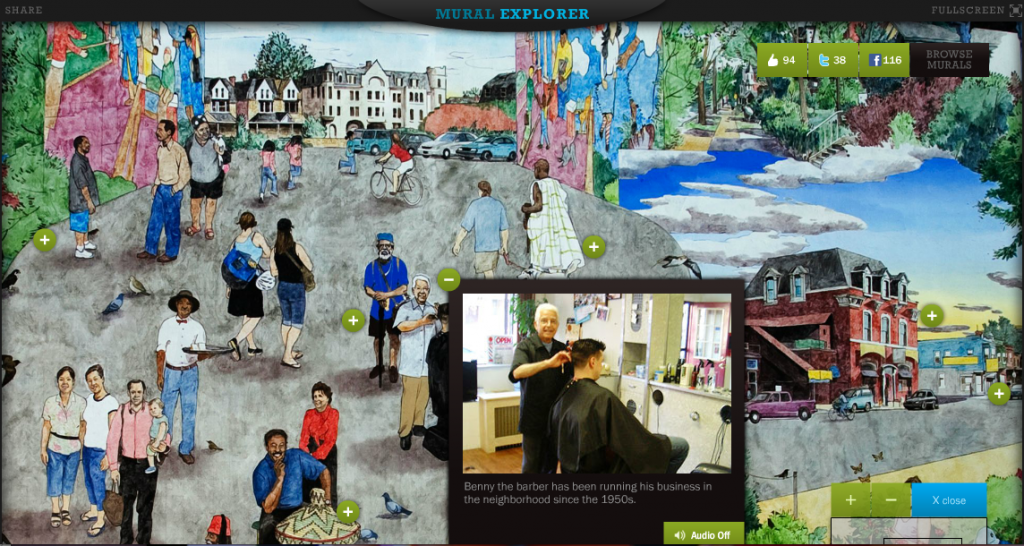

Philadelphia Mural Arts Program’s Mural Explorer allows viewers to zoom in to murals like the above Heart of Baltimore Avenue by David Guinn, and click on each “character” in the mural for a related video. Source: http://explorer.muralarts.org/#/mural/heart_of_baltimore

Information-sharing at public art sites

While online public art tours allow the art-curious to have multi-sensory experiences with art from all over the world without leaving their homes, mobile tours put information at the fingertips of those who incidentally encounter public art on site. Many public art organizations give walking, bike or bus tours of their collections. However, scheduled tours often require a fee to participate and do not necessarily engage “the spontaneous viewer [who] typically has not planned ahead, paid a museum admission, or signed up in advance for a cultural tour” (in the words of Penny Balkin Bach).

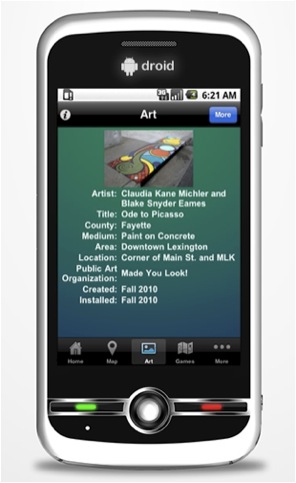

QR codes, links, or phone numbers on physical signage at public art sites can direct passersby to download or dial for more information on a particular public art piece, locate additional art nearby, and, in the case of apps like Kentucky’s Take it ArtSide! Museum Without Walls, locate other cultural tourism activities in the area.

An ongoing project of professor Christine Huskisson of the University of Kentucky and her students, Take it Artside! pinpoints different public art locations around the state, and provides data on cultural institutions, gallery walks, and arts events. The app has several game features: visitors can earn points based on the art sites they “check in” to, and track their fitness routines through an ArtFit game that integrates public art into workouts.

Promoting social interactions and dialogue

In contrast to websites and mobile platforms that house comprehensive archives on public art, social media and photo-sharing platforms can promote ongoing dialogue and activity around the artwork. These sites help public art organizations keep their followers informed about both the art and other related content. For example, NYC-based community mural organization Groundswell often posts articles related to the social justice issues or community organizations depicted in its murals on its Facebook page. Social media also invites visitor-uploaded content (more on this below).

These virtual archives, tours, and apps clearly provide the public art visitor more information about public art—but how can we use those same technologies to learn more about the visitor, and ultimately evaluate the public art itself? It is first worth looking at previous efforts to capture and quantify audience response to public art.

How have public art’s audiences traditionally been studied?

Art historian Harriet Senie has long considered the question of how to study people’s reactions to and behaviors around public art. Each semester, her students at City College of New York are assigned to do a “public art watch.” Every student selects one artwork to study over the course of a school semester, at different times of the day and week, using the following research methods:

- Observation of people’s behavior at public art sites

- Surveys of random passersby in front of public art, through open-ended interview questions such as “Do you know the purpose and significance of the artwork?”, “Have you noticed it before?” and “What do you think of the work?

Similar evaluation laboratories have been conducted by a handful of arts organizations in recent years, usually in partnership with universities or independent researchers. For example, Philadelphia’s Mural Arts Program and researchers at the Yale School of Medicine are undertaking a rigorous program evaluation of MAP’s Porch Light Initiative, which uses mural-making to achieve public health objectives in target communities. Trained volunteers conduct interviews with random community members at each completed mural, offering transit tokens as an incentive. In a spring 2012 study by the Arlington Arts Council, a group of graduate students interviewed passersby at public art sites to determine their interest in and preferences for future public art.

In late 2012, the New York City Department of Transportation’s (DOT’s) Urban Art Program conducted onsite interviews and online surveys to gauge public interest in this nearly five-year-old public art program and advocate for its continuation into a new mayoral administration. DOT required a dedicated manager to oversee the project and train volunteers in conducting the on-site interviews.

Purely observational studies can also yield meaningful results. In the June 2012 issue of Public Art Dialogue, urban design professor and researcher Quentin Stevens details his “empirical observations of [Berlin’s Holocaust Memorial] and visitors’ [often inappropriate] actions around it”—i.e. climbing, striking silly poses, smoking or drinking at the memorial. Stevens observed people’s behavior under different daylight and weather conditions throughout 25 different visits in May and July 2006. This “50 hours of discreet observation…yielded 5000 photographs and 200 video segments documenting the actions of many hundreds of individual visitors.” Stevens concluded that a majority of visitors were perhaps missing the artist’s intent, and ignoring instructional signage nearby.

Interviews and observation require specialized training and sufficient on-site presence to reach a good number of respondents. These methods work well in academic environments or targeted case studies, but are not practical for most arts organizations to implement on a regular basis. Furthermore, they work best when organizations can easily identify both specific audiences to target and specific outcomes to measure using accepted methodologies in a given field. However, many organizations do not know where to begin in identifying such outcomes and indicators, and may not have a need for such in-depth evaluation on an ongoing basis anyway. Still, they might benefit from collecting some kind of visitor feedback after each completed project or across many projects over time. This feedback might start to hint at some possible outcomes and indicators that could eventually direct a more structured study. Can the interactive technologies described earlier, many of which have components that collect users’ responses and track their behaviors, serve this function while simultaneously engaging audiences in dialogue with the artwork itself?

The goals of public art projects and organizations vary widely, as do their definitions of “audience” or “public” (for the sake of this article, I am using the two terms interchangeably). However, there are certain common research questions that typically drive studies of permanent or long-term public art installations:

1. WHO are the audiences of public art? What are their demographics? Are they already involved in the arts? What is their reason for visiting a public art site?

2. HOW MANY people stop and notice the public art/take an interest in it during a given time frame? Does this vary according to factors like time of day or season?

3. WHAT DO PEOPLE THINK of public art? Do they like and identify with it? Do they want to see more public art?

4. WHAT DO PEOPLE KNOW about public art? Do they understand its meaning or significance? Do they want to learn more?

5. WHAT DO PEOPLE DO with public art? For example, is it a meeting place, a backdrop for photos? Do people interact with an artwork in the way intended by the artist/organization? How does the public art impact the public’s experience of an overall site?

6. WHAT DO PEOPLE DO AS A RESULT of public art experiences? For example, are they inspired to find out more about related topics, programs, or places? Do they engage in commercial activity in a given region? Do they recommend the public art to friends?

7. WHAT DO PEOPLE WANT? What type of public art would they like to see most in the future, and what types do they favor over others?

What can we research through interactive media?

In researching this article, I have sought to discover the potential of interactive tools and new technologies to help answer the above questions. So far, they seem most effective at the following:

Tracking the number (and demographics) of users of the tools themselves

Most public art websites and apps have built-in systems such as Google Analytics which track how many people visit in a given time period, which pages get the most traffic, and how people are referred to the sites. Mobile app vendors such as iTunes track number of downloads, while phone companies keep a count of callers. aPA’s Penny Balkin Bach recently reported over 50,000 “audience engagements” with public art via the organization’s Museum Without Walls website, mobile app, and phone tours. Such metrics have assisted in securing funding for Phase II of the project, which will add more artworks and tours.

The fact that “about 90% of aPA’s callers listen through to the end of an audio” is considered strong evidence that the tour content is engaging enough to hold one’s attention; according to Communications Director Jennifer Richards, “It is significant if people stop for three whole minutes on the street next to a public art piece to listen to information about it.”

Unfortunately, this does not allow us to measure the total number of people who experience public art without interactive tools. Capturing the numbers who do, however, still has benefit. Organizations can compare people’s engagements with different public art pieces to hypothesize which are considered most interesting or eye-catching, helping to fine-tune and promote the engagement tools themselves and inform future programming choices.

Portland, OR’s Public Art PDX mobile app has a mechanism for users to submit suggestions for artworks they feel should be added to the online collection, or corrections for mis-located or mis-labeled artworks on the app’s map. Tools like this help gauge general stewardship of public art.

Organizations can also look at how often public art websites, or URLs/QR codes on public art signage, refer visitors to related sites, or vice versa. For example, tracking the number of people who access public art-related content within cultural tourism apps can help make a case for the importance of public art to regional tourism.

Most organizations using interactive tools have not taken the next step toward analyzing who is using these tools, and why. Some mobile apps do ask users for basic profile information like their zip code and email address, and could easily ask for more before allowing usage. Without collecting detailed user data, it is difficult to determine audience members’ cultural or socioeconomic backgrounds, prior knowledge of/interest in art, or motivations for using the engagement tools – all information that is usually gathered in more formal public art audience surveys. Yet in a field where collecting any kind of quantitative data has traditionally been deemed problematic, having this free and user-friendly way to begin to quantify audience engagement with public art is refreshing.

Collecting written anecdotes, comments, and stories

While they may churn out impressive statistics about people interacting with public art, what can these new platforms tell us about how the art impacts the public? Most leaders in the field whom I interviewed agree that collecting and analyzing meaningful qualitative responses via these tools is trickier than simply counting views or “likes.”

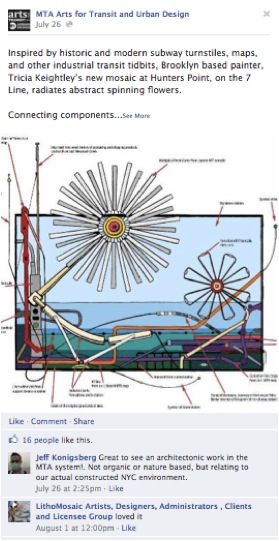

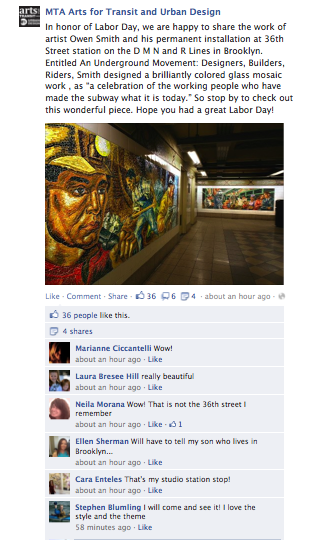

Posting images of public artworks on Facebook can generate feedback on what people think of an artwork and what they might like to see in the future. From the New York City Metropolitan Transit Authority’s Arts for Transit and Urban Design’s Facebook page. Artist: Tricia Keightley.

Even so, feedback gleaned through interactive media can answer some of the questions typically asked in formal public art audience interviews. For example, in the above Facebook comment thread about an artwork in the NYC Arts For Transit collection, Jeff Konigsberg’s response suggests not only his approval of the artwork, but imagery that he and perhaps others would like to see in future subway art. Some of the commentators on the below post, also from the Arts for Transit page, speak to the role that public art plays in riders’ everyday lives; others express intent to visit the artwork again, or tell friends about it. According to Arts for Transit director Sandra Bloodworth, such feedback, while not analyzed or reported formally by her staff, helps “affirm the public’s appreciation” of the work.

A September 3, 2012 post on the MTA Arts for Transit page, featuring Owen Smith’s “An Underground Movement: Designers, Builders, Riders.”

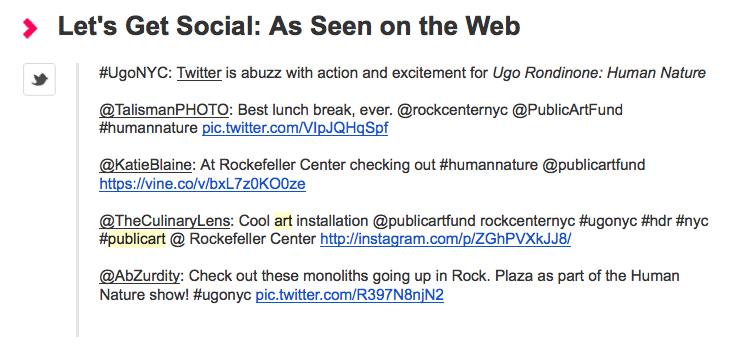

While most other organizations I interviewed are not formally reporting social media feedback, New York City’s Public Art Fund, which commissions several large-scale long-term public art installations per year, cites comments collected on Twitter and Instagram in email newsletters as one way of demonstrating public interest.

In the Public Art Fund’s May 29, 2013 e-newsletter, this Twitter feed is meant to demonstrate public “excitement” for the organization’s installation Ugo Rondinone: Human Nature at NYC’s Rockefeller Center

Feedback that could be interpreted as negative (such as the above example from Public Art Fund’s Facebook page of one user’s interpretation of an artwork’s intent) is less common on social media. Most people probably would not be comfortable bashing an organization’s content on its Facebook wall, for the same reason they would not insult artwork hanging in their friends’ homes in front of their friends. In addition, someone who does not enjoy or care about public art is unlikely to follow a public art organization online.

Comments to news articles and blog posts, however, reveal a more diverse range of opinions. Within the last year, writeups on controversial murals, on Hyperallergic, Huffington Post, and The New York Times’s City Room blog cite lively discussions on Facebook reflecting a broad public’s reactions, and prompted further reader comments. Online comment threads like those above can be mined to identify the most effective arguments for and against an artwork, the same way Facebook and Twitter feeds are commonly used by the news media to cite the public’s reactions to more mainstream debates.

The question is how to spark such rich dialogue online about public art that is not controversial, or especially current and newsworthy. For some organizations, generating any kind of dialogue, positive or negative, is an indicator of a public artwork’s success. Groundswell Executive Director Amy Sananman explains, “We can perhaps look at which murals have been most successful with audience engagements via social media to find out what types of future projects might cause the most discourse.” For an organization like Groundswell that aims to spark dialogue around social issues through public art, this type of analysis could be important in shaping new programming. Groundswell, like many organizations, is still figuring out how best to utilize online comment forums.

Best practices in collecting written feedback

In addition to posting pictures, or signs inviting comment at public art sites, it is important to engage with users’ normal communication channels. Jennifer Richards of The Association for Public Art believes social media is the most natural forum for sparking dialogue. Both aPA’s Museum Without Walls smartphone app and dial-in audio tours have mechanisms for people to share stories about their experiences, but according to Richards, the mobile tours generate only 1-2 voicemail comments per month. By contrast, people comment much more frequently than that on social media posts.

The wording and formatting of posts also matters. Perhaps the main shortfall of many invitations to participate via these interactive tools is their open-endedness, which may inhibit both participation in the first place, and the formulation of meaningful responses. In designing interactive platforms, whether online or mobile, it might be wise to follow Nina Simon’s observation in The Participatory Museum: “Participants thrive on constraints, not open-ended opportunities for self-expression.”

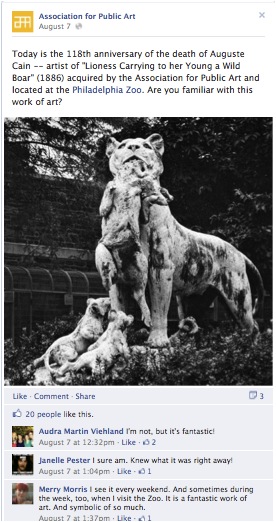

“Name that sculpture” post from August 2012 on the Association for Public Art Facebook page that gauge visitors’ knowledge of historic public sculptures in Philadelphia.

“Name that sculpture” post from March 2013 on the Association for Public Art Facebook page that gauge visitors’ knowledge of historic public sculptures in Philadelphia.

Some organizations are employing such constraints with what seem to be meaningful results. For example, quizzes like the above posted by Association for Public Art on Facebook not only test people’s prior knowledge of public art, but can inspire comments about their opinions and personal experiences. Based on my study of about 10 different organizations’ social media pages, this approach seems to solicit more discussion than simply asking visitors to leave a comment, or advertising a new project with just a photo and title. According to Penny Balkin Bach: “The whole point of our social media effort is to encourage appreciation for CONTENT; so we don’t ask people what they like — we ask them what they know.”

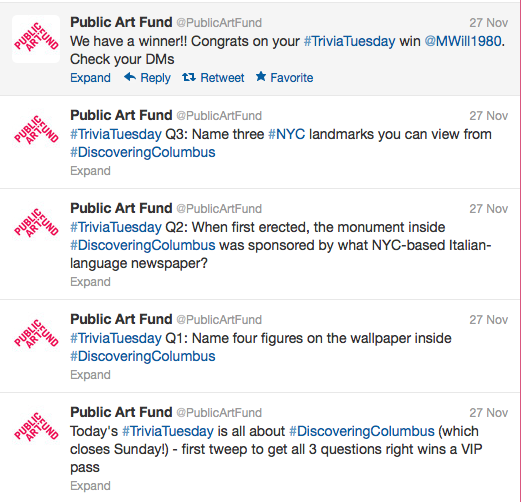

Public Art Fund uses Twitter for its “Trivia Tuesday” contests highlighting current public art exhibitions.

Of course, it is unclear whether these public art quiz examples are truly evaluating the public’s prior knowledge of public art, or engaging them in a quest for more knowledge. Yet regardless of how participants arrive at the “right answer” to a quiz question, it is revealing that so many are interested enough in the art to seek further information about it.

By contrast, posting traditional questionnaires on social media or in mobile apps does not seem to be very effective. So far, the surveys I have seen organizations use on social media have not yielded enough responses to draw any conclusions. A Public Art Fund multiple choice question on Facebook asking people to select their favorite aspect of its Fall 2012 “Discovering Columbus” installation had only five responses, a week after it was posted. Marketing Director Janet Cooper of Dublin, OH’s Dublin Arts Council similarly reported very little use of the feedback survey on the council’s Facebook page.

Interactive media may fail to excite people about taking traditional surveys, but we might consider it as an alternative, more organic means of unearthing public opinion. People who view filling out questionnaires as a chore may be much more likely to engage in a conversation, or play a game, about an artwork on Twitter or Facebook. Freed from answering leading prompts or selecting between limited multiple-choice questions, they might be more likely to offer up unexpected and surprising information.

It is worth noting that several organizations have reported positive outcomes when soliciting responses to public art surveys across multiple interactive channels, with social media as one element in the mix. The City of Albuquerque’s public art program, for example, recently succeeded in collecting both demographic data and opinions about public art from 1300 tourists and local residents through two public art questionnaires, the results of which are summarized on the city’s website and incorporated into a strategic plan. The survey link was “distributed through local and national e-mail listservs and subscriptions, local print and digital news media and tourism outlets,” but director Sherri Brueggemann cites a partnership with a local tourism bureau as especially important in getting so many people to take the survey.

Determining what people are doing with public art: inviting photo and video submissions

Just like stopping to listen to an audio tour or commenting on a social media post, stopping to take and post photos of public art is an indication that the art has caught one’s attention. For the Public Art Fund and Association for Public Art among other organizations, directing visitors to photo-sharing links via signage at public art sites has been especially effective at soliciting user submissions.

Public Art Fund’s Director of Communications Kellie Honeycutt reports, “Visitor-submitted photos help us see how people are actually interacting with the artwork.” I first experimented with this concept as the co-artist of Pallet City, a complex interactive sculpture made from recycled shipping pallets for the 2010 FIGMENT Sculpture Garden on New York City’s Governors Island. The sculpture had different components that each encouraged a type of action, indicated by signage. In addition, my collaborator and I put signs up all over our project telling people to email pictures of themselves interacting with the sculpture. To our pleasant surprise, we received an average of three submissions each weekend the project was open. This was enough to convince us not only that people were noticing the project but that we were achieving our goal of fostering a range of participatory experiences. People were clearly noticing the signs on the sculpture that labeled each section’s intended purpose. For example, we received many photos of people doing somersaults, dances, and even juggling on a stage area labeled “perform.”

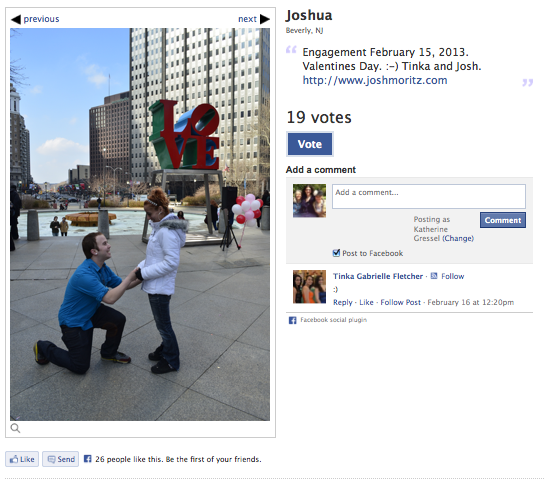

Photo competitions can be an especially efficacious and easy way to get a wide range of photo submissions in a short time. Association for Public Art recently held a competition asking for the best photos of the iconic Robert Indiana “Love” sculpture in Philadelphia submitted via Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. aPA offered gift cards as prizes to three winners and a free printed poster of all the photos to the general public. According to aPA’s Jennifer Richards, “I almost wish we had told people to submit a picture of a public art work they ‘love’ the most. Then we would have known better what types of public art people love and why.” The competition was set up using a Facebook contest feature that allowed page visitors to vote on the winners.

Example of user-submitted photo, and voters’ comments, at the Association for Public Art’s “Love ” photo competition: https://www.facebook.com/assocforPublicArt?ref=ts&fref=ts

Example of user-submitted photo, and voters’ comments, at the Association for Public Art’s “Love” photo competition

While the “Love” competition did not lend itself to comparisons between different types of public art in Philadelphia, the 180 submissions give a glimpse into the range of ways people view and interact with the sculpture–from using it as a backdrop for marriage proposals and photographs in formal wear, to sporting it as a tattoo–and the sculpture’s important role in placemaking and boosting civic pride. Some photo submissions prompted additional comments from Facebook users—many speaking to their “love” of Philadelphia (see above).

How do we analyze and make use of all this feedback?

Filtering through all of this information on a regular basis to find evidence of public art’s impact is a challenge, particularly when individual comments don’t comprise anything close to a representative sample of a broad public’s opinions or experiences. However, those comments suggest ways in which a larger group of people might be impacted, and could be the basis for designing more structured logic models or questionnaires around public art.

Each time a new substantive comment or photo comes in from any source, it could be archived by topic, resulting in a collection that can be periodically analyzed to discover trends, or mined for juicy quotes. Jennifer Richards from aPA suggests establishing 3-4 “buckets,” or different categories of comments, and having someone assign each online comment to a different bucket as it comes in. This is not something the organization has put into practice yet, however.

Richards also stresses the importance of storytelling, not just number-crunching, in reporting on the impact of one’s work. While they may be used infrequently, the mobile tour “leave a comment” channels have produced some good anecdotes commonly used in grant proposals for the audio tour program itself, such as the following audio-recorded message a local trolley driver left after he took one of the cell phone tours, which, according to Penny Balkin Bach, “reinforced the broad reach of MWW:AUDIO”:

“I drive a Philadelphia trolley, and drive pass number 12 (the All Wars Memorial to Colored Soldiers and Sailors) everyday…and I think it’s wonderful that you have this program set up. It was educational. It was educational for me, and emotional, as an African-American. It makes me feel much better to be a part of Philadelphia.”

Comments like this are certainly evidence of the reach of a tour, but could also be considered evidence of the ability of the public art to connect to local residents, once they know more information about it.

Further questions and suggestions

Interactive tools can be tweaked to be more directed towards evaluation, as can our methods of analyzing the feedback that comes in. The tools still cannot replace rigorous, formal evaluation initiatives. Organizations must consider the following points when determining how to factor interactive media into an overall evaluation plan:

Reaching a more random audience sample

The audiences who take surveys or make comments via an organization’s Web site, social media page, or mailing list are most often people who are already supporters of, and familiar with, the organization’s work. In some cases, especially when the art is very much rooted in a local community, an online commentator may have actually participated in helping select or create the artwork.

Also, not everyone has access to interactive public art engagement tools, or chooses to use them. The City of Albuquerque’s public art survey, for example, found that while “70% [of respondents] feel that public art would be better served with signage and/or interpretative information associated with public art…97% say they have never used a public art smartphone app.”

Emily Colassaco, manager of the NYC DOT’s Urban Art Program, believes the best way to reach the broadest public is still through in-person surveys with random passersby at public art sites. The majority of respondents to DOT’s web-based survey were already familiar with the program.

Yet even if the majority of comments or photos do come from people who already support an organization, or have even participated in public art creation, these comments can still help tell a valuable story, and inform the questions that can be asked of a wider sample of the public, if and when the time is appropriate.

Distinguishing between evaluating the impact of public art on its own and evaluating the impact of learning about public art via these new educational tools

So far, most organizations using these new tools cite goals and metrics that may assess audience response to the engagement tools themselves, rather than audience response to public art. As an alternative to studying responses to interactive platforms designed by public art organizations, looking through visitor-uploaded photos of public art on a platform like Flickr, or simply Googling the name of a public art piece and seeing what comes up on a wide range of websites, might be a possible way to study the public’s unmediated experience of the art.

However, often education and evaluation go hand in hand. If we go out and ask for people’s comments about a public art piece, we’re also opening up opportunities for people to ask and learn about the artwork, the surrounding community, and the commissioning/partnering organizations. By giving people accessible information about a public art piece, we are in turn empowering them to speak about it and other public art in a more informed way. It may be advantageous to integrate evaluation of art projects into an organization’s outreach or communications activities, rather than treat it as a separate expenditure of time and resources. Yet because education or evaluation are likely to happen simultaneously, it is especially important to set clear goals for what we are trying to evaluate, and which tools are appropriate to use.

To give an example, if an organization’s goal is to use community murals to educate local communities about important issues, it might be a stretch to post photos of two completed murals on Facebook at the exact same time, and conclude that the one with more “likes” or comments is more successful at achieving this goal. It is difficult to know what external factors motivate participation online, and if the people participating are even members of target communities. But perhaps it is possible to compare how easy it is to design engaging posts, mobile tours or web pages or around certain artworks over others, and look at the content of users’ responses to these engagement efforts to find evidence of both planned and unexpected learning outcomes.

Project specifics and organizational capacity

It is easier to launch, and evaluate, a big user participation campaign for a hyped-up public art installation that only lasts a few months, like the Public Art Fund’s Discovering Columbus in NYC’s Columbus Circle, than it is to determine whether people notice, or care about, a sculpture or subway mosaic that was created years ago. To invigorate interest in Philadelphia’s historic public art collections, aPA worked with a special grant to develop Museum Without Walls; many permanent public art collections do not have this type of support, and are more focused on the regular commissioning of new work.

Final remarks

Though their effectiveness as evaluation and engagement tools may vary based on the specifics of a public art organization or project, platforms like social media and photo-sharing sites are almost universally accessible and widely used, as are website analytics. While there is still the challenge of sorting through the overwhelming amount of feedback coming in through so many different sources, these free tools can be useful knowledge-gathering mechanisms for public art organizations. In addition to engaging people in new ways with public art, they are effective at collecting stories, photos, and, in some cases, even numbers that can at least hint at possible impacts of public art that were previously much more difficult to document on a regular basis. These platforms are also beginning to integrate public art evaluation into people’s everyday lives, by linking public art commentary to social, enjoyable activities in which the public is already actively engaged.