This article summarizes lessons learned, as well as recommendations going forward for foundations, government agencies, individual philanthropists, and others providing resources to support the arts. A subsequently published piece contains further recommendations aimed at people who commission and/or conduct arts research.

For the past three years and change, Createquity’s mission has been to research “the most important issues in the arts and what we can do about them.” During that time, in networking meetings with potential donors or friends of the organization, I would often get questions along the lines of, “so what are the most important issues in the arts?” Or people might ask for advice on where a donor should give if she were interested in making the most impact in the field. For a long time, I resisted answering these kinds of questions directly, because Createquity’s approach involved deeply investigating a wide range of potential issues before coming to firm conclusions about which ones might be most deserving of our attention, or what kinds of actions we might want to advocate for. Now, however, with Createquity having announced its intention to cease operations at the end of 2017, the time has come to share what we do know – even if there are still significant gaps in that knowledge – and what we think it means for those trying to improve people’s lives through the arts.

Please note: the analysis that follows is a hybrid of formal evidence review, informed opinion based on our collective firsthand experiences working in the field, and logical inference. While we have tried to make it as clear as possible throughout, we welcome questions about what is (and isn’t) backing up specific assertions, and will respond to them in the comments as they come in.

Consider Your Funding from an Ecosystem Perspective

From the very beginning, Createquity has advocated for an ecosystem-level view in arts funding. We’ve actually gone so far as to write out a detailed definition of what a healthy arts ecosystem looks like in practice.

Okay, that sounds nice, but what does it actually mean? Think about it like this. An ecosystem is kind of like a big theatrical production. There are a bunch of different roles to be played, and effective casting in those roles is crucial to giving the audience a good show. Right?

So, the huge difference between a theatrical production and the arts ecosystem is that there is no director making those casting decisions. A bunch of people just walk up to the stage, pick a part they want to play, and go to it. Some of those people might be better suited to playing a different role than the one they chose. In some cases there are two (or more) people duplicating the same part, and constantly stepping on each other’s toes. Another actor might play a role brilliantly, but disappear for the second half, or refuse to share the stage with anyone else. It’s all just a big uncoordinated mess.

Our only hope of bringing some order to this chaos is to recognize that, whenever we design strategy for a new program or redesign an old program, we’re casting ourselves in one of these roles. And it might seem obvious to say, but I’ll say it anyway since it’s so important: when designing the role we want to play, we must ask ourselves, who else is in the cast? What are the roles that aren’t currently being covered? And which of those roles am I or my organization best suited for?

I want to specifically call out that, in my experience, the highest-leverage decision points are often the ones least likely to receive this level of scrutiny. Sure, you may have set up a committee or commissioned an external consultant to decide how to refine and move forward on some specific program that you piloted last year. But how much due diligence went into deciding why your organization exists at all? Its geographic focus and target population? The originating logic behind its flagship initiatives?

People are fond of calling for more leadership in the arts sector. But the thing about an ecosystem is that it is fundamentally leaderless. Which means that we all have to be leaders if any leadership is going to happen. And to me, in the context of grantmaking, that means all of us taking the time to thoroughly understand the arts funding landscape before deciding what role is most appropriate for us to play.

A good rule of thumb is to start with the premise that every other funder is not doing this – in other words, that every other funder is less strategic than you. That flies in the face of the philosophy of humble servant leadership that we’re taught to model in philanthropy. Even so, I would argue that it is a useful working assumption, because if you believe it, then you must believe that it is your responsibility to be the actor in the ecosystem who fills the gaps, who does what needs to be done and what no one else is willing to do. It is up to you to find out what what is needed and neglected, and prioritize that over what might get the best press or the fanciest gala tickets.

And the reality is that my assertion above is likely to be more true than not for anybody reading this. The majority of philanthropic contributions to the arts comes from individual donors, most of whom have a very transactional relationship with specific charities they support and who are notoriously difficult to organize as a constituency. A landmark study of donor motivations commissioned by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation concluded that only 16% of individual major donors are motivated by impact, and only 4% consider the effectiveness of an organization the “key driver” of a gift; I would guess that these numbers are even lower for arts donors. Another fifth or so of arts philanthropy comes from corporations, many of which are motivated less by the mission outcomes achieved by grantees and sponsorship recipients than by the benefits those relationships can offer to the brand.

The overarching lesson to take from all of this is that it’s crucial to conceive of arts philanthropy broadly. Resist the temptation to overspecify the solution before you truly understand the problem. We see a lot of programs, especially at organizations that give out smaller-sized grants, that have tons of restrictions on what can be funded, for how long, how the money must be spent, etc. While there may be reasons (like internal capacity constraints) that justify these decisions from the perspective of the granting organization, at a system-wide level this practice results in intractable gaps in the funding landscape and strongly distorts incentives for prospective grantees. Wherever possible, we recommend pushing for the maximum level of flexibility that your donor or ultimate stakeholder is comfortable with – and if the donor/stakeholder is you, pushing yourself to be as clear as possible about the outcomes you’re interested in while being as open-minded as possible about the pathways to accomplishing them.

Regardless of the more specific advice below, this is the most important. Take the time to understand how your work fits into the overall landscape of needs and opportunities in the sector. An eager audience is depending on you to do it.

Don’t Put Your Name on That Fancy Building

Several years ago, the philosopher and ethicist Peter Singer made a splash in the arts community by writing a New York Times op-ed piece entitled “Good Charity, Bad Charity,” which compared the merits of donating to help construct a new museum wing and donating to an organization fighting a disease that can cause blindness in the developing world. Whipping together a back-of-the-envelope cost-benefit analysis, Singer wrote, “a donation to prevent trachoma offers at least 10 times the value of giving to the museum,” adding, “the answer is clear enough.”

Predictably, the arts blogosphere kind of freaked out, writing response after response defending or deflecting the practice of giving to the arts while characterizing Singer’s argument as “a shocker,” “absurd,” and “tyrannical.” It turns out that Singer’s piece was part of a broader outreach effort on behalf of a movement called effective altruism, which is devoted to the idea of figuring out how to do the most good with the money and resources available to you. Effective altruists believe that answering such questions involves hard tradeoffs, and necessitates a discipline called “cause prioritization” at the very highest strategic level. Not surprisingly, the arts often serve as a convenient example for effective altruists of the sort of “bad” philanthropy to be avoided in favor of higher-potential giving opportunities.

Our instincts may tell us to get upset about this, but the reality is that museum wings are easy targets for effective altruists for a reason. There is an argument to be made that capital investments in fancy buildings are the single worst category of arts philanthropy there is, and may be among the most wasteful uses of (non-fraudulent) philanthropy in general.

How so? First of all, capital projects are enormously expensive. According to “Set in Stone: Building America’s New Generation of Arts Facilities, 1994-2008,” the most comprehensive review of the data on capital construction in the arts that we know of, the average cost of a building constructed by or for a nonprofit arts organization around the turn of the millennium was at least $21 million in 2005 dollars (equivalent to $26 million in 2017). At the extremes, a single project can cost as much as hundreds of millions of dollars, more than the entire annual budget of the National Endowment for the Arts. Each year, arts organizations spend upwards of $1 billion on such campaigns, with most of that money coming from private philanthropy. Foundations devoted at least 10% and possibly as much as 38% of their arts budgets to capital projects in 2014, according to figures from the Foundation Center.

One major problem with capital projects sucking up so much donor interest is that they disproportionately benefit wealthy, established organizations presenting European art forms, often smack in the middle of places with very large populations of color. Moreover, artists rarely see a penny of this money; the most immediate beneficiaries of these expenditures are construction companies and their suppliers. Beyond equity concerns, however, capital projects frequently turn out to be bad investments even on their own terms: “Set in Stone” documents numerous cases of projects that failed to meet visitation benchmarks, exceeded expectations for ongoing maintenance costs, and/or ran over budget (by an average of 82% in the case of performing arts centers). The authors “found compelling evidence that the supply of cultural facilities exceeded demand during the years of the building boom … especially when coupled with the number of organizations [they] studied that experienced financial difficulties after completing a building project.”

This is not to say, of course, that every capital investment is a bad idea, or that arts organizations should never build new buildings. But given that buildings often come with ample opportunities to lure individual donors to the table (via naming rights, gala invitations, etc.), it’s even harder to defend institutional grantmakers’ investment in capital projects when there are so many more neglected priorities in the sector.

Where to Put That Money Instead

I’m admittedly biased on this one, but I believe strongly that our field has badly underinvested in knowledge. Annually, according to the Foundation Center figures cited above, just 2% of foundation arts grant dollars and 0.7% of grants go to research and evaluation. If my experience over the past decade is any guide, individual donors add virtually nothing to this total.

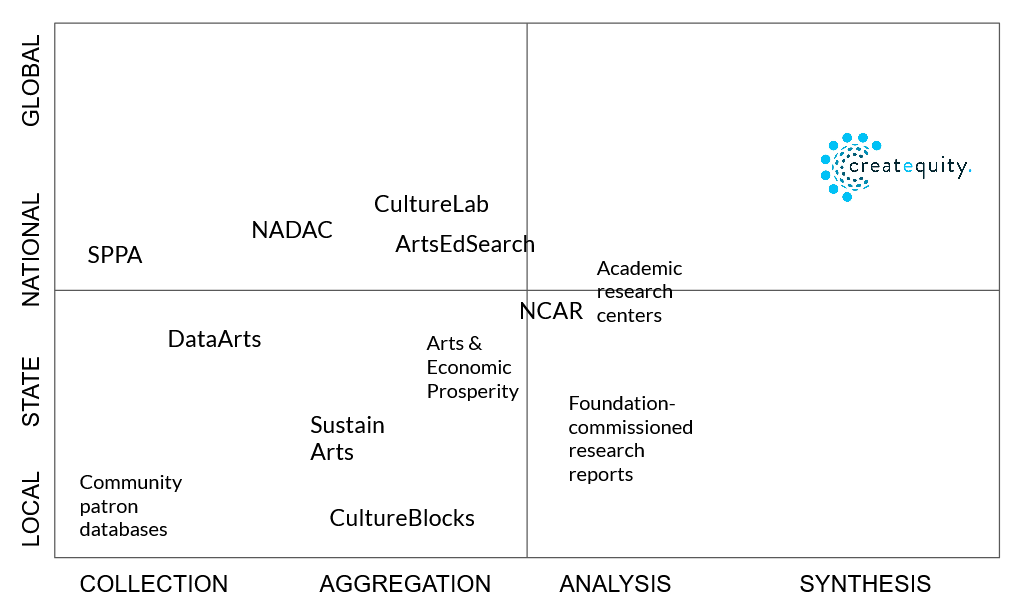

Even more concerning than the overall level of spending is the distribution of those resources. Existing research initiatives are heavily weighted toward primary data collection and analysis for specific, one-off projects, and most are limited in scope to a single geographic area, arts discipline, or both. As part of Createquity’s business planning process in 2016, we put together an exploratory graph of arts research initiatives, plotting them by breadth of geographic scope and where they sit on the spectrum between isolated data-gathering and more holistic efforts at building knowledge. You’ll see that, prior to its demise, Createquity stood virtually alone in the sector in focusing on the cumulative construction of knowledge through synthesis and interpretation of existing research – and yet even Createquity’s paltry annual operating budget for this work proved impossible to sustain.

This is a tremendously neglected area of arts funding, and that neglect has real consequences for how we all do our work. There is ample evidence that arts leaders are increasingly overloaded with information and need help making sense of it all. Because our field has not invested in the resources to make it possible to do so, it is likely that every day we are missing out on opportunities to shape the arts ecosystem for the better because we do not understand the evidence that’s already right in front of us. Indeed, the choices we are making may even be causing active harm.

This is a tremendously neglected area of arts funding, and that neglect has real consequences for how we all do our work. There is ample evidence that arts leaders are increasingly overloaded with information and need help making sense of it all. Because our field has not invested in the resources to make it possible to do so, it is likely that every day we are missing out on opportunities to shape the arts ecosystem for the better because we do not understand the evidence that’s already right in front of us. Indeed, the choices we are making may even be causing active harm.

As Createquity’s experience demonstrates, filling this gap and others related to our field’s knowledge infrastructure will require a new will to invest in field-building more generally. One of the persistent structural factors holding back such efforts is the difficulty of engaging individual donors in field-building conversations. Despite their importance to the arts ecosystem generally, in 15 years of working in this field I have yet to encounter a single effective strategy for organizing and communicating to individual donors about field leadership issues. Overall, individual donors represent a tremendous untapped opportunity to increase the arts field’s leadership capacity and overall potential for impact.

Moving on to more programmatic issues, there is a strong case to make that a worthy focus of arts philanthropy is advocacy to restore arts education cuts, especially for underprivileged youth at all age levels. Our judgment on this issue derives from several related observations. First, there is a lot of baseline evidence that arts education is beneficial for children, especially for those who have not yet entered formal schooling. Second, we know that in the United States, arts education cuts have disproportionately fallen on low-income families and black and Latino children. Finally, we have some glimmers of evidence that disadvantaged children benefit disproportionately from exposure to arts education. These factors, combined with the incredibly broad reach of arts education as compared with other types of arts interventions, suggest that evidence-based arts funders will find arts education of great interest. With that said, we should add the caveat that it is an arena already receiving a lot of attention, which may mean that much more work is necessary to create the political conditions for donor impact.

Speaking of evidence, Createquity’s review of the literature on the wellbeing benefits of the arts found that some of the strongest available research indicates that older adults and adults in clinical settings can benefit disproportionately from the arts. Participatory activities like singing, in particular, help to reduce anxiety and depression, improve subjective wellbeing, and even fend off the onset of dementia. And when it comes to attendance, according to the NEA’s research, nearly a quarter of adults aged 55 and older in persistent poor health were interested in going to an exhibit or performance in the past year but were not able to, which is a greater percentage than any other demographic examined in the report. This appears to be a highly neglected focus area; I am not aware of arts programs at any foundations in the United States with more than $1 billion in assets that have older adults or people in hospitals as the primary target audience.

Finally, on a more speculative note, it seems likely that the health of the arts ecosystem in the United States and beyond is more generally tied up with the health of the social safety net in those places. Many of the problems in the arts are reflections of larger issues that affect wide swaths of society. While the details of how they play out in the arts may be unique to the field, we can’t hope to solve them by focusing solely on our sector. When Createquity began developing a formal research agenda three years ago, I assured my colleagues on the editorial team that if our inquiry were to reveal that the most important issue in the arts is not an arts issue at all, they could count on me to make that case. Sure enough, after a decade of closely observing trends and shifts in arts policy, I’m more confident than ever that we are wasting our time if we are not taking society-wide issues like health care, wealth inequality, rapid technological progress, and structural racism into account when we develop arts and culture policy. We would do well to shift our working assumptions such that we believe an issue affecting the arts is not specific to the arts until proven otherwise, and therefore the solution to the issue is likely to live outside the arts as well. How can we work more effectively across issue-area and industry silos to make unified progress on these challenges that affect us all so deeply?

Suggestions for Individual Donors This Holiday Season

Createquity has always focused on the broad strokes of arts policy and philanthropy, and we’ve never positioned ourselves as a source of recommendations for individual charities to support. Still, every once in awhile I get requests to make those recommendations, particularly from people who don’t know the arts field very well and do not have strong existing commitments to specific organizations.

Although our recommendations are not as strongly rooted in evidence as those of, say, GiveWell, we do have a few ideas for donors whose primary area of concern is the United States:

- If you are interested in knowledge-building and field leadership issues in the arts, we recommend supporting Grantmakers in the Arts. GIA is the only entity deeply engaging grantmakers across disciplines, geographies, and sector boundaries, and is therefore best positioned to make strides organizing this constituency for greater impact. GIA has an existing knowledge-building function that we would like to see become significantly more robust. We’ve been pleased to see that the organization has begun engaging more foundation trustees in recent years, as well as more arts grantmakers outside the United States. In addition, it might be a good thing for the field if more individual donors, especially high-net-worth donors, were part of GIA’s revenue base and governing constituency.

- If you are interested in supporting arts education nationally, a donation to the Kennedy Center for the national Turnaround Arts program may not be a bad idea. An evaluation of Turnaround Arts from several years ago offered reasonably promising evidence for the effectiveness of its ambitious model (which uses arts integration as a holistic strategy to “turn around” failing schools), and the program has since expanded considerably. GIA and Americans for the Arts have national arts education advocacy initiatives, though we are not in a position to judge their effectiveness. Arts Education Partnership is a national arts education leadership organization that also has a research database called ArtsEdSearch.

- If you are interested in supporting arts opportunities for older adults or in clinical settings, several organizations in the US and UK have programs with solid evidence behind them, including TimeSlips, Elders Share the Arts, and Sing for Your Life’s Silver Song Clubs.

- If you are interested in supporting organizations in your local area, consider that smaller, grassroots arts organizations, particularly those rooted in communities of color, are more likely to be under-resourced relative to the benefit they are capable of providing. If you are not from the community that leads the organization you’re interested in supporting, however, do your homework first to confirm that your help is wanted before you offer it. Many local communities also have well-regarded arts education initiatives, such as Big Thought in Dallas and Ingenuity, Inc. in Chicago.

- Finally, while not a donation, we strongly suggest supporting ArtsJournal by purchasing a premium email subscription ($28/year) or classified advertising. ArtsJournal is a crucial news aggregation resource that has been the source of more than half the links offered in Createquity’s Twitter feed and monthly Newsroom articles over the past several years. Its content is generated from following hundreds of both mainstream and niche media publications and methodically curating the most relevant and thought-provoking content, six days a week, 52 weeks a year. Information resources like these are notoriously fragile in the digital era, and ArtsJournal is no exception: founder Doug McLennan has seemingly not taken a vacation from it in the ten years that Createquity has existed. Supporting ArtsJournal is a great option in particular for small-dollar donors who are not itemizing their deductions.

As much as we wish we could, we are unfortunately not in a position to make recommendations regarding charities outside of the United States at this time. We would love to see someone else take on that challenge, however!

Parting Thoughts

To be a philanthropist, whether the money is yours or simply has been entrusted to you, is a remarkable privilege in every sense of the word. The world is probably never going to see the day when literally everyone seeking to make the world a better place through the arts does so strategically and wholly without regard to self-interest. But the more we can nudge individuals, organizations, and actions in that direction, the more meaningful all of our work will become.

The magic of knowledge is that it is highly leveragable. What you have just read is a summary of a decade of inquiry into the inner workings and external context of the arts ecosystem. If the insights from that exercise ultimately guide even a mere handful of important decisions by well-placed individuals, it will all have been worth it in the end.

Until then, in this season of holiday generosity, and for many more on the horizon, we wish you happy giving and many happy (impact-adjusted) returns.