(Arts Policy Library week at Createquity finishes up with this monster review of Americans for the Arts’s flagship economic impact report, Arts & Economic Prosperity III. Written in 2009 during a brief moment between graduating from school and starting my present job when I actually had lots of time on my hands, this is the longest post we’ve ever published and the one that famously prompted Rob Weinert-Kendt to declare Createquity “so amazingly good it’s almost in its own category of resource; ‘blog’ hardly does it justice.” You’ll want to set aside an hour or so for the full effect, but if you’re short on time, you can also check out the Cliffs Notes. -IDM)

Perhaps no arts-related research study is cited as frequently in the mainstream media these days as Americans for the Arts’s gargantuan economic impact survey, Arts & Economic Prosperity III. Its key message, that the nonprofit arts sector is responsible for $166.2 billion in economic activity nationwide, has been hammered home relentlessly to policymakers, politicians, grantmakers, and arts managers around the country since the report’s initial publication in 2007. Americans for the Arts clearly sees the report itself, along with the general theme of economic relevance, as central to its overall advocacy strategy: as AFTA’s Director of State and Local Government Affairs, Jay Dick, put it while speaking at the 2007 Wyoming Arts Summit,

In the past, when we went to do funding for the arts, we said, “fund the arts, it’s good for the soul.” […] That’s true, [but] it doesn’t work anymore. You know, we have to have a business argument for it. So, “fund the arts because it’s good for the soul—and they bring to the jobs to the economy and they bring taxes back into the [government].” That’s what we have to do.

Not everybody, however, is convinced. For one thing, the dual role that AFTA assumes as impartial researcher and impassioned advocate renders the report vulnerable to criticism on the grounds of bias, criticism that the report itself goes to great lengths to counter. Moreover, even assuming the numbers are accurate, thinkers from Tyler Cowen to Greg Sandow have assailed the very concept of economic impact studies and their utility in advocacy discussions. Indeed, when last we paid a visit to the Arts Policy Library, the authors of Gifts of the Muse: Reframing the Debate About the Benefits of the Arts argued that relying too heavily on economic and other “instrumental” arguments for the arts is a trap, pointing out that that economic impact studies

…receive criticism because most of them do not consider the relative effects of spending on the arts versus other forms of consumption—that is, they fail to consider the opportunity costs of arts spending. Some economists dispute the validity of the multipliers used in economic studies because they assume that spending on the arts represents a net addition to a local economy rather than simply a substitute for other types of spending.

The tension between the two approaches led journalist John Stoehr to set up a kind of debate between the AFTA and RAND texts in a 2007 article for the Savannah Morning News, a debate that in Stoehr’s mind Gifts of the Muse ultimately won.

As always, though, much is lost in a public debate about a study when most of the participants have only read the press release. The full Arts & Economic Prosperity III report contains some 314 pages of findings, facts, and figures, including 27 multipage data tables and one of the most thorough explanations of methodology I’ve ever encountered in a research report. So let’s dive in and find out what Arts & Economic Prosperity III actually has to say about the economic impact of nonprofit arts organizations in the United States.

Summary

The first thing to understand about Arts & Economic Prosperity III is that it is comprised of many studies in one. It makes use of an innovative distributed data-gathering strategy that involved partnerships with organizations and agencies in some 156 study areas across all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The study areas included 116 cities and counties, 35 multi-county regions, and five entire states. These 156 partners were tasked with identifying and coding the universe of nonprofit arts organizations in their area, using the Urban Institute’s NTEE codes as a guide; disseminating, collecting, and reviewing organizational expenditure surveys; conducting audience-intercept surveys at a minimum of 18 representative events in the area; and paying a modest cost-sharing fee (though the study authors take care to note that no community was turned away out of inability to pay this fee). The partners collectively produced 6,080 completed organizational surveys1 and interviewed some 94,478 audience members about their spending over the course of 2004 and 2005.

Americans for the Arts then collected this data and created four sets of numbers with it. First, it tabulated the total organizational expenditures in each community, noting the breakdown of artistic versus administrative versus capital expenses, and calculated the averages for each of six community cohorts based on population size, labeled A-F (0-49,999, 50,000-99,999, 100,000-249,999, 250,000-499,999, 500,000-999,999, and 1 million and up). Second, AFTA tabulated the audience expenditures related to arts events in each community (excluding the cost of admission), and calculated the averages in the same way. Third, researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology ran both the organizational and audience expenditure numbers through a sophisticated econometric tool called an input/output model to estimate the cumulative local transactions that those expenditures might cause in each community. Though those results aren’t reported in the study directly, the researchers ran them through another set of models to come up with estimated resident household income, employment figures, and state and local government revenue that could be attributed to the organizational and audience expenditures. Finally, taking the averages for each of the six population groups, AFTA calculated national estimates for all six of the metrics listed above by mapping the averages on to the populations of the 12,662 largest cities in the United States. (Note: only the 116 cities and counties, the smallest unit studied, were used in the calculation of the national estimates.)

The resulting figures will look familiar to anyone who’s read a news story about arts funding lately. Nonprofit arts organizations account for $63.1 billion in organizational spending and $103.1 billion in audience spending nationally, for a total annual industry footprint of $166.2 billion. Collectively, these expenditures support an estimated 5.7 million full-time equivalent jobs, $104.2 billion in annual household income, $7.9 billion in local government revenue, $9.1 billion in state government revenue, and $12.6 billion in federal income tax revenue.

The study reports that the typical attendee forked out $27.79 per event on top of any cost of admission—what the study calls induced spending—on things like meals, refreshments, clothing, lodging, souvenirs, child care, and transportation. As one might expect, the numbers vary dramatically between local and nonlocal attendees (nonlocal defined as traveling from outside the county). Tourists spent more than twice as much on average as residents on event-related items ($40.19 vs. $19.53), the biggest increases coming from single-night lodging (more than tenfold) and transportation (nearly threefold). Tourists also spent 40-50% more on average than residents on meals/refreshments, gifts/souvenirs, and “other.”

Arts & Economic Prosperity III is, as the title implies, the third study in a series. (A fourth is planned for launch next year.) Comparisons to the previous edition, using data collected in 2000, show a growth of 24% in the five years between studies—a rate that sounds impressive at first, but was actually outpaced slightly by growth in overall US GDP during the same period. Twenty-five communities were represented in both the second and third editions of the study; this group grew more than twice as fast as the national estimates.

Some of the most interesting statistics from the study aren’t the ones that usually make it into the press release or the media alerts. For example, the 6,080 participating organizations reported an average of 125 volunteers who donated a mean of 45.3 hours each in a year. That’s a simply astounding level of volunteerism. The total of 191,499 hours is valued at $3.4 million using Independent Sector’s 2007 valuation of volunteer time. Those hours have no economic impact as defined by the study (and are not included in the national estimates of economic activity), but the study authors take care to note that they add much value to artistic communities anyway. In addition, 71% of responding organizations received in-kind support of one kind or another, valued at an average of $47,906 per organization. The largest source of such support was corporations at 61%, with the balance from individuals, local and state government, local arts organizations, and other.

Though not reported in the study text, the audience demographics (Tables 25-27) are worth a look. Women consistently outnumbered men by nearly a 2:1 margin in almost every community. Assuming the survey samples were representative, we can conclude that arts audiences are VERY well-educated (more than 83% reported having a college degree, and fully a third had one or more graduate degrees) as well as quite affluent (30% reported a household income of more than $100,000). More than 80% of audience members are 35 or older. These results tracked quite consistently between urban and rural areas and between residents and tourists, with the exception that audiences tended to be a bit richer and better-educated in big cities.

I also found Table 9 notable for its breakdown of organizational expenditures on artists. In almost all communities, artists themselves get a truly tiny slice of the money that goes to support the nonprofit arts. Their share was only 11% overall, and ranged as low as 7% in the group of the smallest cities and counties. In a few areas, like Lauderdale County, MS and the entirety of Northwest Minnesota, the total amount spent on artists in a year was not even enough to pay one person’s salary.

Analysis

Since there seem to be a number of misperceptions about Arts & Economic Prosperity III in the media and elsewhere, perhaps the most helpful step I can take at the beginning is simply to delineate what the study is and what it is not. I can tell you that Arts & Economic Prosperity III is:

- A serious study. One thing that becomes clear from reading the entire report is that the people behind Arts & Economic Prosperity III invested significant time and care into getting the numbers right. As I mentioned earlier, A&EP III has one of the most comprehensive explanations of methodology I’ve seen in a research study – a full ten pages of information representing one-third of the non-appendix portion of the report. The authors even make a valiant effort to explain the mechanics of input/output analysis, an advanced econometric technique involving matrix algebra and other graduate-level technical sophistications. Time and again, as questions popped into my mind while I was reading along, I would find them answered in the next section or by the end of the report. Wary of any perception of bias on the part of an advocacy organization tasked with making the case for government funding of the arts, researchers took numerous steps to ensure that the final estimates would not be skewed too far in favor of that conclusion. These steps included large decisions with major implications—the country’s two largest cities, New York and Los Angeles, were excluded from individual study in part because of their outlier status among American arts scenes; areas with unusually high economic activity for their population group, like Teton County, WY and Laguna Beach, CA, were excluded from other national estimates—and small details—like the fact that the audience expenditure survey checked to make sure respondents were over 18, or that organizations collected data throughout the year in order to guard against effects of seasonality.

- A legitimate estimate of total annual nonprofit arts organization and event-related audience expenditures in the United States. Even if you find yourself confused or unconvinced by the input/output model, that $166.2 billion number has nothing to do with it. The organization expenditure estimate is a direct extrapolation from the responses of 6,080 survey participants (which is quite a robust sample) based on the populations of the communities in which they operate. There’s nothing mysterious about this part of the study.Likewise, the audience expenditures—which don’t include tickets or admission prices—are extrapolations of the information from 94,478 survey respondents and everyone in their party (so, in actuality, a sample of nearly 300,000). By excluding airfare and more than one night’s worth or lodging, researchers did their best to limit their inquiry to expenditures directly linked to arts events that would mostly be staying in the local area.

- Clear evidence that the arts are a big deal in this country. The core takeaway of Arts & Economic Prosperity III – that “the arts mean business” – is amply demonstrated by the data. $166.2 billion is a lot of money, well more than one-thousand times the direct support provided by the National Endowment for the Arts in 2005. The $63.1 billion represented by the organizational expenditures alone is more than the revenue figures for spectator sports, furniture stores, coal mining, or the hunting, fishing, and logging industries combined. And as the authors point out, most industries can’t claim the same kind of “induced” spending—related payments made by consumers to third parties in connection with a core purchase—that the arts can. Even if the numbers aren’t dead on—a possibility I’ll explore in a bit—the point is clear: nonprofit arts organizations play a far more central role in the nation’s economy than commonly believed.

On the other hand, Arts & Economic Prosperity III is not:

- A perfect study. Despite the authors’ seriousness of intent, the study does contain a few errors, idiosyncrasies, and other less than ideal aspects of its construction. These range from embarrassing but ultimately unimportant mistakes like the mislabeling of the audience income demographics in Tables 25-27 (the last column in each table should read “$100,000 or More” instead of “$120,000 or More”) to potentially more significant issues like the inclusion of both Miami and Miami-Dade County among the 116 cities and counties used for the national estimates, which would lead to an over-representation of Miami’s organizations and audiences in the sample. Other issues will be examined when we take a look at the actual numbers.

- A demonstration that the arts cause economic growth. This is perhaps the single most prevalent myth about Arts & Economic Prosperity III and economic impact studies in general, a myth that is in no way dispelled by language like “the nonprofit arts industry generates $166.2 billion in economic activity every year,” that often accompanies the report. Merely counting up the activity associated with the arts in that community doesn’t show that the arts created that activity. Indeed, they easily could have just pointed it in a different direction. If there were no arts, would the audiences who spent $40 to buy dinner across the street have gone hungry instead? Would the office bookkeeper for the local museum not have found another job elsewhere? As I understand it, the arts (or anything else) can cause a net local increase ineconomic activity under traditional definitions essentially in two ways: 1) if they satisfy an unmet need such that people are motivated to spend more money on the arts than they would have spent on other things, thus inducing demand and ultimately driving a higher standard of living; and 2) if they draw money into a community from outside of it. The arts can actually make a pretty decent case for the latter on a local level, thanks to cultural tourism. But once you combine all of those local communities together to make a national estimate, all of those “nonresidents” of your county—with the exception of international travelers—suddenly become residents of the good ol’ USA, and the economic activity associated with the arts is no longer being drawn in from outside the community but merely shifted around within it. As for the first way of creating value, it’s anyone’s guess as to whether and how much that really happens. Essentially, we would need evidence that the same people, on average, are willing to spend more money over the course of a year to attend arts events than they would if there were no arts events to attend. So willing, in fact, that they would take steps in their lives to ensure that they have more money to spend on such things, which (by economic logic) would mean that they would increase their own productivity and value to society, thus making us all better off. No one, to my knowledge, has conducted a study like that, though some researchers have made strides in showing a causal relationship between arts activity and other indicators like housing prices.

- Particularly useful for policy decisions on its own. Let’s say I have some money to give out to improve the city, and I have to decide how to spend it. You come to me and you say, “you should spend that money on nonprofit arts organizations. Nonprofit arts organizations spend a lot of money.” I reply, “umm…okay, that’s interesting.” You go on: “nonprofit arts organizations employ a lot of people.” “So do our pharmaceutical and insurance industries,” I answer. “Should we subsidize them as well?” Finally, you bring out the big guns. “Nonprofit arts organizations produce revenue for your tax base.” “Well, clearly you are already doing a great job of that without my support,” I conclude. “I don’t see a reason why I should give you any.” Do you see how most of these arguments, in a vacuum, are kind of non sequiturs? If one is making an economic argument, policymakers need to know not just what the arts do now but what they can do in the future with an additional investment—their investment. And they need to know how that compares with other potential recipients for that investment. I believe that there are ways to do this, but unfortunately, this particular study is hardly…

- A study of the arts’ “return on investment.” Out of all the report’s assertions, the only one I’d describe as downright false appears right there in the introductory letter on page one—and never again in the report:

Our industry also generates nearly $30 billion in revenue to local, state and federal governments each year. By comparison, the three levels of government collectively spend less than $4 billion annually to support arts and culture—a spectacular 7:1 return on investment that would even thrill Wall Street veterans.

It’s only a seed, but it’s been enough to sprout numerous other attempts to use this logic (like in this piece from earlier in the month in Miami-Dade County). This much is true—a 7:1 return on investment would indeed thrill Wall Street veterans. It’s too bad the examples aren’t remotely comparable. The $4 billion in government investment and $30 billion in government revenue are two different beasts, apples and oranges. As the report itself tells us, nonprofit arts organizational expenditures total $63.1 billion—which means that the $4 billion coming from the government only accounts for about 6% of this total. Take away that 6%, and you’d still have 94% of those expenditures left—and, presumably, something like 94% of the tax revenues. So, that $4 billion in government investment is really only “responsible” for that last 6%—which turns out to be about $1.9 billion, or considerably less than a 7:1 return (more like 0.5:1, for those keeping count). Now, in fairness, the real story is probably more complex than this—surely the government’s impact is not strictly linear, but makes certain projects possible where none had been before, and communities may be able to leverage that support in other ways. But to realize what a junk statistic this is, think about it this way: if a state, oh, let’s say Pennsylvania, were to get rid of its arts funding entirely, all of the sudden it would be able to claim an infinite return on investment from any arts-related tax or other revenues that come in after that! I’m not sure this is really the line we want to be pushing in these battles.

Now that we understand what A&EP III is trying to do, let’s take a close look at the numbers the researchers actually came up with. I’ll divide these into five categories: the organizational expenditures, the audience expenditures, the volunteer contributions, the input-output model, and the national estimates.

Organizational expenditures

The collection of the organizational expenditure data for each community was probably the simplest aspect of the study, so I think it’s reasonable to assume that, in most areas, the numbers represent decent estimates. A few caveats do apply, however, which I’ve listed with the direction in which they are likely to have skewed the totals (if any):

- First, it worries me a little that the partner organization in each community was given the autonomy to implement the study themselves. While it was probably the key factor in making the scale of the study possible, this distributed approach opens up a number of quality control and consistency issues. For example, who from the organizations was conducting the surveys? Was it senior management? Program staff? Interns? LIKELY IMPACT: UNKNOWN

- The report mentions that the Urban Institute’s NTEE designations were used as a starting point for identifying relevant arts nonprofits in their area. Hopefully, partners would have gone the extra mile to edit those lists, but I can tell you from experience that going by the NTEE codes will tend to result in missed organizations, sometimes important ones, that are coded incorrectly or not at all. LIKELY IMPACT: SKEW LOW

- The study only counted the numbers for organizations that responded to the survey, which means that for communities that saw less than 100% response (which was most of them), there’s almost certainly an undercount. (It also means that communities that had higher response rates were over-represented in the national estimates.) Response rates ranged from 10.4% to 100%, with an average of 41.3%. LIKELY IMPACT: SKEW LOW

- Though responding organizations were asked not to include grants to other arts organizations, any payments to other arts organizations (for example, a presenter paying a nonprofit chamber ensemble, or renting performance space from another nonprofit) could result in double-counting. LIKELY IMPACT: SKEW HIGH

- When you get down to the itemized level, there are some bizarre oddities in the data that, taken together, throw a bit of a shadow on the rest of the numbers. For example, in Table 9, Allegheny County (Pittsburgh) arts organizations are shown as spending nearly eight times as much on artists as Philadelphia, despite having only a third of the total expenditures. Similarly, Jefferson County, AL (Birmingham) is shown as spending more than three times as much on artists as Baltimore, despite budgets only 40% the size. LIKELY IMPACT: UNKNOWN

Audience expenditures

A&EP III employed the audience-intercept method for collecting information about audience expenditures, which from what I can gather is similar to the method used for exit polling in national elections. The caution I mentioned above about the autonomy of the partner organizations applies even more strongly to this portion of the study, as administering survey instruments in person is something usually done by professionals. The survey asked audience members not to report expenditures on airfare, presumably because most of that spending would not impact the local community (also because it’s unlikely that most tourists had flown to the area specifically to see that one event, which is the rationale behind counting only one night of lodging). Other notes and caveats include:

- Audience members provided information about their entire party, which might have decreased the reliability of the data since the practice assumes that respondents knew what other people in their party spent. I’d think this would be more likely to result in undercounting (missed purchases) than overcounting. LIKELY IMPACT: SKEW LOW

- Any spending on concessions at the event (e.g., buying a glass of wine in the lobby at intermission) would be double-counted, since that money would become revenue for the organization and eventually show up in its expenditures. I believe the same is true for items bought at museum gift shops. LIKELY IMPACT: SKEW HIGH

- Though audience members were instructed to report lodging expenses for the night of the event only, it’s a bit questionable how attributable some of these expenditures really were to the arts event. For example, if someone bought an outfit to wear that night, does that mean they wouldn’t have bought the same outfit on some other occasion? If someone was in town overnight, does it mean that they were there specifically for that event? LIKELY IMPACT: SKEW HIGH

Volunteer contributions

As mentioned in the previous section, the volunteer hours reported by nonprofit arts organizations are extraordinarily high. According to the study, volunteers supply the labor equivalent of two full-time staff positions to the average arts organization each year. Upon closer examination of the numbers, I couldn’t find any obvious red flags—while there’s some variation, nearly all communities reported a higher level of volunteerism than I would have expected, even when considering the contributions of board members, etc. I can think of only two plausible explanations. One is that organizations must be counting unpaid internships. The other is that some, especially smaller, organizations may be counting uncompensated time put in by founders or artistic/executive directors, which is likely to be substantial in many cases. These are not the kinds of things that normally come to mind when I think of “volunteer work,” but of course that is what they are, so I guess I’m inclined to take the results at face value. The valuation of volunteer time at $3.4 million comes from Independent Sector’s Giving and Volunteering in the United States 2006, which pegs the value of an average volunteer hour at $18.04 in FY05.

Input/output model

As explained by the report, an input/output model consists of “systems of mathematical equations that combine statistical methods and economic theory” that trace “how many times a dollar is respent within the local economy before it leaks out” and quantify “the economic impact of each round of spending.” The ”economic impact” in question is no more and no less than transactions: if I pay you $20 to serve me food, I have increased economic impact by $20 according to this definition. I won’t attempt to recreate the report’s detailed and extremely technical explanation of how the input/output model works; you can read it for yourself if you like. The basic idea is that for each community, a team led by the former chair of the school of economics at Georgia Tech, Bill Schaffer, constructed a matrix of the dollar flow between 533 industries based on data from the Department of Commerce and local tax records. After adjusting to include only local transactions, this table was then simplified to a matrix of purchase patterns of 32 industries plus households. The table was then run through an iterative model that, at each stage, sought to calculate the local requirements in terms of output to make possible the numbers seen in the previous iteration of the table. After a certain number of rounds (I think 12, but it’s a little hard to tell from the description), the numbers are all added up to get the total cumulative transactions made possible by an infusion of the amount of money represented in the organization and audience expenditures.

I don’t really have any complaint with the input/output model itself—it was constructed by a trained professional, and without having access to the actual spreadsheets and models used, there’s no way for me to verify its conclusions independently. The main issue is more conceptual: namely, that the model takes for granted that all of the money coming in as a result of organizational and audience expenditures is new money, money that would not have been available to the community otherwise. But of course this isn’t true: if people weren’t working as or for artists, and going out to see arts events, they’d probably be doing something else that would involve money—quite possibly more money than there is in the arts, given the high education levels of many in the field. One way to deal with this, at least on a local level, would be to simply exclude the spending of residents, figuring that what we care about is new money brought into the community by those outside of it. This methodology would break down significantly at the level of a national estimate, however. Perhaps this is why the study authors admit,

…as in any professional field, there is disagreement about procedures, jargon, and the best way to determine results. Ask 12 artists to define art and you will get 24 answers; expect the same of economists. You may meet an economist who believes that these studies should be done differently (for example, a cost-benefit analysis of the arts).

Indeed, I would have been very interested to see the results of a cost-benefit analysis, as it would seem to me to be a more relevant measure of the value of public investment in the arts. However, the input/output model is what we have, and so it is up to us to understand properly what it means. As with the expenditure totals, the impacts on things like employment, household income, and tax revenue are associations rather than causal links. The arts may account for 5.7 million jobs nationally, but that doesn’t mean that they’ve added 5.7 million jobs to the economy that wouldn’t be there otherwise.

National estimates

At first glance, one would assume that the national estimates of organizational and audience expenditures are almost certainly skewed low. As mentioned earlier, the study leaves out specific estimates for our nation’s two largest cities, New York and Los Angeles, instead assigning them the averages for the 1-million-and-up population group. This decision was made, according to AFTA’s Senior Director of Research Services, Ben Davidson, thanks in part to cost considerations as well as a desire to avoid overinflating the national totals. By how much does this downplay the overall national estimates of economic activity? Well, the average for the Group F (population 1,000,000+) bucket of cities and counties is $408 million in total expenditures by organizations and audiences. Two estimates for organizational expenditures alone are $5.8 billion for NYC and $1.5 billion for LA; assuming a similar spread on the audience side, we’re probably looking at a gap in the ballpark of $13 billion caused by not measuring those two cities directly. Furthermore, an untold amount of activity is left out because the study tabulated spending figures and estimated audience totals only from organizations that responded to the survey. One would hope that the most significant organizations in each community were more often than not in the responding column, but even so it’s likely that a fair amount of economic activity in the 156 study regions simply was not counted.

Despite the factors mentioned above, I think that there remains a pretty compelling reason to think that the national estimates are actually overinflated after all. The reason is simple, but easily missed. It is selection bias among the 156 study regions—and specifically, among the 15 communities in the smallest population category, that of cities and counties containing fewer than 50,000 people.

Think about it this way: in order to participate in the study, a community needed to have a nonprofit organization or government agency with the following attributes: a) a programmatic focus on the arts (preferably exclusively on the arts); b) the staff capacity, expertise, and interest to manage a research project that involved identifying and surveying all of the nonprofit arts organizations in their area and conducting in-person audience surveys at a minimum of 18 events throughout the year; and c) the financial capacity to participate in AFTA’s cost-sharing fee (note: though this fee was supposedly waived for any partners that couldn’t afford to pay it, it’s unclear to what extent partners who didn’t take the time to ask were aware that this was an option—the call for participants for Arts & Economic Prosperity IV, for example, does not mention the fee waiver.)

Out of the thousands of cities and counties in the United States with populations of less than 50,000, how many of them do you think meet these criteria? Do you think that there might be some important differences between the ones that did and chose to participate in the study versus the ones that didn’t? Like, for example, a LOT more arts organizations and arts spending?

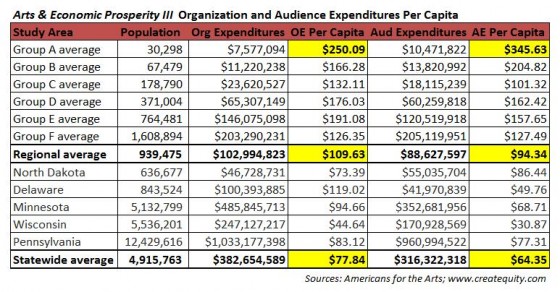

Luckily, Arts & Economic Prosperity III studied a few different kinds of regions, including entire states, making some interesting comparative analysis possible. I put together a table below with the average economic activity per capita for each of the six population subgroups for the cities and counties, as well as the average for the 35 multi-county regions and the estimates for each of the five states studied. First, looking at the different population subgroups, rather than per-capita spending going down as populations get smaller and more spread-out as one might expect, there’s a big jump in both organization and audience expenditures from group B (50,000-99,999) to group A (under 50,000). More interesting, however, is the comparison between the cities and counties and the multi-county regions, and especially the entire states. A statewide count would not suffer from the selection bias discussed here: instead, it would incorporate urban and rural areas in proportions not all that dissimilar from the rest of the country. Similarly, some of the multi-county regions studied occupy large swaths of land, and their arts organizations could pool their resources to meet the requirements for participation in the study.

The average expenditures in the smallest city and county population group are absolutely off the charts. Group A cities’ and counties’ arts organizations spent nearly two and a half times as much per capita as the regional average and more than three times as much as the statewide average. Their audiences spent more than five times as much as the statewide average.2 It’s not just group A, though—all of the city and county subgroups have per capita expenditures higher than those for the regions and states. In fact, the highest average for a state in the study was lower than the lowest average for a city/county subgroup. That’s not random. That’s selection bias.

So what happens when your national estimate is based on the city and county averages in Groups A-F (and especially sky-high group A) rather than the lower regional and statewide averages? Remember, the estimate is based on the populations of the 12,662 largest cities in the US—all the ones with populations of at least 500, according to Davidson—and more than 90% of those cities would have been in Group A.

Well, we can do a little exercise to sense-check the numbers. The total nonprofit arts organization expenditures nationally should be roughly equal to total arts organization revenues. I checked the Giving USA statistics for arts and culture, which include contributions from individuals, foundations, and corporations but not government support or earned income, and got an estimate of about $12 billion for 2006. Then I checked data from the National and Local Profiles of Cultural Support study that looked at the typical breakdown of income sources for nonprofit arts organizations and pegged the contribution of private donations from individuals, foundations, and corporations at 25% as of 1998. So if $12 billion accounts for 25% of arts organizations’ budgets, their total budgets should be around $48 billion—not outrageously off, but nevertheless only about three-quarters of AFTA’s $63.1 billion estimate. And 25% was the lowest estimate I found on the web of private contributions to nonprofit arts budgets. Now, this is not conclusive–it’s certainly possible that Giving USA itself undercounts the revenues of nonprofit arts organizations and foundation contributions. And maybe the breakdown of income sources was dramatically different in 2005 for whatever reason. But given the information we have, I think it’s fair to assume that AFTA’s expenditure numbers are probably not that conservative after all.3

Implications

So is Jay Dick right that we need “a business argument” for the arts? I think he is, and I think Arts & Economic Prosperity III is helpful in that regard—to an extent.

As I read Arts & Economic Prosperity III, I found myself coming back again and again to the theme of language. A&EP III is a serious study, one worthy of our attention and use for advocacy and research purposes. However, some of its potential impact is undermined by the hyperbolic language with which it is often presented to the press and politicians. The first several pages of the report are cluttered with spurious or misleading statistics and graphs that distract from the more strongly supported of the study’s findings. For example, on page seven there’s a graph that shows “jobs supported by nonprofit arts” apparently outnumbering several categories of specific professions, including lawyers, farmers, and computer programmers. Of course, there’s a crucial difference: the arts number includes all jobs supported by the industry (according to the study’s calculations–so, not just artists and arts organization employees but people at Staples, Guitar Center, etc.), rather than jobs in specific professions. Any of those industries—software, legal, agriculture—could likely draw up a similar graph to make itself look good. Or take the consistent use of the word “generates” when talking about the economic transactions associated with arts organizations and audiences, which clearly implies a causal connection that has not been shown to exist. There is a whole section entitled “Nonprofit Arts & Culture: A Growth Industry” that conveniently downplays the fact that the arts grew at rate slower than overall GDP between this study and the last one. And then there’s that bogus 7:1 “return on investment” figure that we dissected earlier. These overreaches ultimately provide fuel to the economic impact naysayers such as Cowen and Sandow, and may only encourage those with an axe to grind against the arts to sharpen their instruments.

That’s a shame, because I think there is a real case to be made for the economic impact of the arts. As we’ve seen in several smaller studies that focused on particular geographic areas, there seems to be strong evidence for a causal relationship between the density and proximity of arts providers today and growth in local real estate prices tomorrow. That, pure and simple, is economic impact right there. Furthermore, though I’ve spent much of this article talking about substitution effects and pooh-poohing the notion that all of the spending associated with the arts represents spending that wouldn’t have occurred otherwise, it would be equally foolish to assert that none of that spending represents new value being created, either through bringing money into the area via cultural tourism or improving quality of life such that people are willing to spend more than they would have otherwise.4 Even if the arts turn out not to be the absolute most surefire way to spur economic development in local communities in all cases, I think we can assume that they often represent one component of a successful growth strategy. And certainly we can argue with a clear conscience that the arts support real jobs, that they play a much bigger role in the economy than commonly assumed, and that public subsidization for the arts is not the same thing as a giveaway.

For the fourth edition of Arts & Economic Prosperity, which is in its planning stages right now, I hope Americans for the Arts will take advantage of its strong local partnerships and infrastructure to help fill in some of the gaps in what we know. The building blocks for causal analysis are already there. In fact, the audience questionnaire for A&EP III did ask audience members the reason why they were in town that evening, and one of the options was “I am here specifically to attend this arts event.” Alas, this information never found it into the data tables or the report itself. Another question on the survey could ask audience members what they would have done with their time and money instead that afternoon or evening if they had not attended the event. Even though this wouldn’t be the most reliable data in the world due to its reliance on self-reports of hypothetical situations, it would nevertheless get us a step closer to an understanding of the true economic impact of arts events. Finally, at the organization level, it seems obvious that government investment in the arts must have some return, we just have to be careful about attributing outcomes to it that would have happened anyway. So why not ask organizations where they would make cuts if deprived of government funds as part of the expenditure survey? If you really wanted to go nuts with it, you could literally ask them to submit a revised budget that doesn’t include government support and see what they end up cutting. This last approach, needless to say, would be difficult to pull off, but one wouldn’t need to do it everywhere to get some idea of what the overall picture would tell you. A few sample communities might be sufficient as a pilot.

We should be grateful to Americans for the Arts for investing as much time, capital, and seriousness of purpose into this research as it has. While there are a number of paths open for improvement of this work, the foundation upon which those improvements would be laid is solid. I look forward to finding out what Arts & Economic Prosperity IV will have in store for us.

1Since the study focused on nonprofit arts organizations, spending by for-profit creative firms and industries was excluded, as was any spending by individual artists. However, government-sponsored arts councils and presenting facilities were part of the study, and so were select programs embedded within non-arts organizations, such as university presenters.

2In fairness, the authors did exclude Laguna Beach, CA from the organizational expenditures and Teton County, WY from the audience expenditures when calculating the national estimates. However, even with this precaution in place, the averages still compute to $210.76 and $251.93 respectively–far above the next-highest number in each category.

3Part of the problem, really, is that organizational and especially audience expenditures just aren’t that strongly correlated with population. Looking at the data tables, one sees huge variances in nonresident spending totals between cities in the same category, like Miami Beach ($72.2 million) vs. Lauderdale County, MS ($502k), or Philadelphia County ($565 million) vs. Suffolk County, NY ($5.7 million). I’m guessing there are a lot more Lauderdale Counties in this country than Miami Beaches. (Indeed, according to Davidson, this is the reason why the cities with a population of less than 500 were not included in the estimates.) If it were possible to extrapolate the national estimates using local estimates of economic activity rather than population size, this approach might yield a more reliable result.

4While this study documents attendance at arts events by nonresidents, it does not do much to show that their travel plans were dictated by those events. However, it does point us to resources that go farther: a 2001 study by Travel Industry Association of America and Partners in Tourism found that 65% of adult travelers attended an arts and culture event while on trip 50+ miles away from home, and that 32% of these (i.e., about 20% total) stayed longer because of event. And of those that stayed longer, 57% (or about 11% of all travelers) extended their trips by one of more nights. So we can infer from this that arts and culture events were directly responsible for one or more nights of lodging expenses for approximately 11% of adult long-range travelers in 2001.