(This week in Createquity Reruns, we’re celebrating Talia Gibas, who has been involved with the site in one way or another continuously since applying for the Createquity Fellowship two years ago. Now a stalwart member of the editorial team, she has been our resident arts education expert for all that time. Here, in one of her first articles for Createquity, she breaks down the phenomenon of “shared delivery” for clueless people like me who need a helping hand to understand the lingo. -IDM)

When some brave soul writes an updated history of arts education in the United States (any takers?) I think he or she will describe the early-to-mid-2000s as an ambitious era. The arts education sector, mirroring the broader arts field and the constantly reforming field of education, is having larger and broader conversations about impact, outcomes and sustainability. In the process it’s moving toward large and broader models of best practice such as the idea of “shared delivery” (also known as “blended delivery” and the “three-legged stool model”). Shared delivery has been in vogue for the last few years. It was a central topic of conversation at the Grantmakers in the Arts Conference in 2008. Americans for the Arts identifies shared delivery as a key component to a broader approach called “coordinated delivery” – which, in turn, was identified as a major arts education trend in 2010. My own initiative, Arts for All, upholds shared delivery as integral to the vision of ensuring high quality arts education for all students in Los Angeles County.

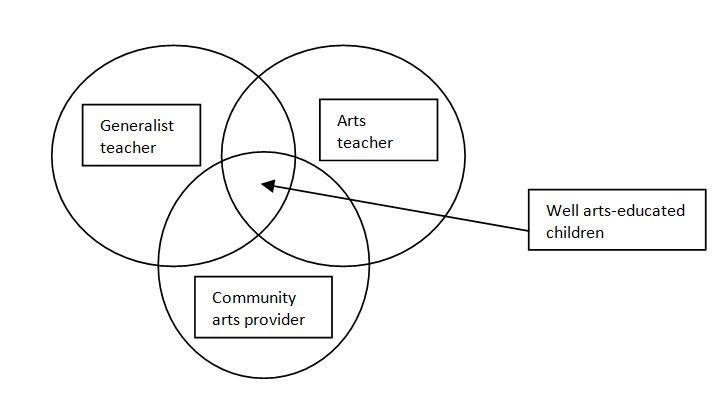

In the K-12 public school setting, shared delivery envisions students receiving arts instruction from three distinct parties: 1) generalist elementary school teachers, 2) arts specialists, and 3) teaching artists and/or community arts organizations. Under this model, the three collaborate to provide visual and performing arts programs to children. The generalist teacher integrates the arts throughout daily lessons across subject areas, the specialist hones in on skills and content specific to his or her art form, and the teaching artist supports one or both while engaging directly with students and providing the perspective of a working arts professional. The model posits that each of these three roles is of equal importance. While there are different attempts to represent this idea graphically (try here, here and here (page 17)), all fall back on a basic visual of three concentric circles:

Shared delivery does not reflect what I or, based on anecdotal evidence, the majority of people within my age bracket received in terms of arts education. My fifth grade generalist teacher was a woman named Mrs. Gonzalez. I saw her every day, and she taught me math, reading, science, history and so forth. My school had a visual arts specialist, Ms. Peters, whom I saw once a week. Art never really came up during my math/reading/science/history lessons, and math/reading/science/history never really came up during my art lessons, so if Mrs. Gonzalez and Ms. Peters worked together behind the scenes, their collaboration wasn’t readily apparent to me. The only visiting teaching artists I recall encountering in elementary school were members of a theater company who performed an abridged version of Macbeth during a school-wide assembly in our cafeteria. Afterwards they sat on plastic chairs and answered questions. They stayed for about an hour, and we never saw them again.

Were I the beneficiary of a true shared delivery model of arts education, those actors would have come into my classroom and taught me theater for a number of weeks or months alongside Mrs. Gonzalez, who would in turn be learning theater techniques to use in other subject areas, all the while also working with Ms. Peters to draw connections to visual art. I may have had a teaching artist work with me and my teacher in third or fourth grade so that I understood the elements of visual art by the time I got to Ms. Peters in fifth grade. I would have had a lot more art in my life, period.

Shared delivery is ambitious and, on a broad scale, largely theoretical. As with much in arts education, the roots of the model stretch back to budget cuts in public schools beginning in the 1970s, when broad anti-tax sentiment gripped the country. In California, this sentiment manifested in a state-wide ballot measure capping property tax rates, at a time when California’s school districts received the bulk of their funding from local property taxes. When the measure passed, schools braced for a huge – according to this 1978 estimate, more than 33%– drop in revenue. Similar cuts impacted state and local education budgets across the country; according to the Center for Arts Education, New York City had a robust curriculum in all four art forms before the city’s 1970s fiscal crisis pushed it to the brink of bankruptcy. How many visual and performing arts teachers were laid off as a result across the country is difficult to determine, but it appears that schools took a pretty big hit from which they never fully recovered. In 2007, per SRI’s analysis of arts education across California, 61% of the state’s schools did not have even one full-time equivalent arts specialist on staff.

Concurrent with these cuts, the field of teaching artistry was formalizing. As described in NORC at the University of Chicago’s 2011 report, “Teaching Artists and the Future of Education,”

Artists slowly began entering schools in the 1950s. Their roles were initially limited to introducing students to the excitement of live performance… That began changing in the mid-1960s… Artists in the Schools became one of the first programs of the new National Endowment for the Arts. By the mid-1970s, Young Audiences, Urban Gateways, Lincoln Center Institute of Arts Education, and other organizations in major cities were sending artists to schools to teach workshops and residencies.

These teaching artists brought with them what NORC calls a “new kinds of arts pedagogy” that “modified the more hierarchical pedagogy of the conservatories, rooted in European classical tradition, to find an approach based on the principles that the arts are for everyone.” As “quasi-outsiders” in the public school system, teaching artists could experiment with new ways of teaching the visual and performing arts, many of which went on to become best practices. Given the loss of arts specialists, teaching artistry also allowed many students who otherwise may never had access to a certain art form to learn directly from a professional. Schools, in turn, clearly saw the benefit. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in 2009-10 42% of elementary schools across the country reported partnerships or collaborations with cultural or community organizations, 31% with individual artists, 29% with museums or galleries, and 26% with performing arts centers.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, the standards-and-accountability movement took full force across the United States, with states defining or redefining what students should know and be able to do in each grade level and in each content area, including the arts. National visual and performing arts standards were developed in 1994 (with a revision due out later this year), and every state except for Iowa and Nebraska has adopted its own standards for the arts at the elementary or secondary level, or both. The quality of the state standards varies, but for the most part, they represent newly codified aspirations regarding what public school students should know in all art forms.

Alongside those aspirations came a realization that meeting the standards required changing how teaching artists and classroom teachers (both generalists and specialists) interact. A simple “service provider” arrangement, in which schools select and arts organizations deliver from a list of pre-designed programs, left classroom teachers and teaching artists operating in silos, with the teacher essentially “handing off” responsibility for arts instruction to a short-term visitor. As noted in the National Guild for Community Arts Education’s Partners in Excellence handbook, this approach “does not take full advantage of the expertise of both the artists and the educators to create in-depth, pedagogically sound arts experiences for children and professional enrichment for teachers.” The field’s definition of best practice shifted accordingly to include much higher levels of collaboration between teaching artists and classroom teachers. The teaching artist or arts organization’s goal is not to deliver a certain number of lessons to students, but to make sure something is left behind when the artist walks out of the classroom – be it lasting effects on students, a long-term increase in teachers’ skills, a changed school culture, or all of the above. Teachers, therefore, learn alongside students so that they can, in theory, carry on the arts instruction when the teaching artist is not there.

Hence, the shared delivery model engages not only students but also teachers, and posits that a number of individuals, and a lot of planning time, are needed to ensure that students learn what we want them to learn in dance, music, visual art and theater during the school day. The need for collaboration and planning is not unique to the arts in schools – numerous education initiatives (and even President Obama’s education platform) recognize that classroom teachers don’t have enough opportunities to work and reflect with their peers across subject areas. Shared delivery of arts education does, however, envision a lot of different visual and performing arts cooks in the proverbial education kitchen. Those cooks need to be paid and that kitchen needs supplies. Done well, shared delivery may have a fantastic return on investment, but collaboration takes time, and time takes money. As noted by SRI,

While integrating arts instruction into other subject areas may be pedagogically powerful and may maximize students’ instructional day, the collaboration necessary to make it successful appears to require a substantial amount of teacher time… This time came either from teacher contract time dedicated for planning or professional development or through schools paying to have two adults in the classroom – or both.

Shared delivery isn’t cheap, which begs the question of whether it’s realistic. Many schools, not to mention arts organizations, are gearing up for their fourth consecutive year of budget cuts. We can’t argue that having three parties work together to provide arts education during the school day is more economically efficient than just having one or two – it’s not – and we are particularly vulnerable if we assume the need for multiple parties is unique to the arts. Granted, “shared delivery of math instruction” sounds pretty weird: imagine if Ms. Gonzales, while teaching my class about variables and basic algebra, had been collaborating with a math specialist whom we also saw once a week, and we’d had periodic visits from a friendly community partner from, say, a local investment or research firm, and that partner led us through hands-on projects that allowed us to see how using letters to stand in for numbers applies to real-life, day-to-day careers and decisions – hold up, that sounds amazing.

The real costs/benefits of this approach have yet to be known, but in my mind, the promise of the shared delivery model is not that it allows us to “restore” arts education in a cheaper or easier way. True shared delivery is such a far cry from what most of us received growing up that its relevance to a (possibly mythical) “golden age” for arts education within classrooms is dubious. Instead, it aspires for an entirely new vision of how all students receive arts instruction – and perhaps, by extension, how education works in general. The promise of the model is that it acknowledges deep and meaningful learning, whether in nuclear physics or dance, happens when different experiences, concepts and skills overlap. You can’t expect to learn everything from a single source any more than you can consider yourself an expert on a topic by hunkering down alone and reading a textbook. Colleagues in other subject areas are aware of this; several math and science grant programs run through the Department of Education and National Science Foundation feature an emphasis on partnerships similar to what I described above, with the latter going so far as to aim to “promote institutional and organizational change in education systems — from kindergarten through graduate school.”

We may not be entirely alone, then, in the scale of what we hope to achieve. We even may be ahead of the curve in recognizing how deeply those concentric circles need to overlap in order to be effective, and in developing best practices for how that overlap happens. In order to take the model further, we need to pay more attention to the all-too-neglected shared spaces between the arts specialist and community arts provider, and between the arts specialist and generalist. We also need to be meticulous in documenting and discussing how the circles come together and stay together over time, and assertive in sharing what we are learning with colleagues from other subject areas. As complex as it is, the very notion of shared delivery reflects how far we have come as a field: from trying to “catch up” to other subjects in schools, to pioneering collaborations between teachers, schools and communities that those other subjects may very well learn from. With luck, future students will thank us for our ambition.