(For all the talk of how artists face challenges making a living, they’re not alone. Former Createquity Fellow Jena Lee takes a look here at how individuals in other fields, including fashion and even law, are singing the winner-take-all blues. Some of the lyrics might sound surprisingly familiar. -IDM)

“Will Work 4 Food,” a mural by New York street artist Lord Scotch 79. Photo credit: carnagenyc

Philip Glass drove a taxi, Patti Smith was a bookstore clerk, and William Faulkner worked the night shift at a power plant. It’s an old story: when they aren’t working in their studios, recording, or rehearsing for upcoming auditions, many, if not most artists spend their time at another job that brings in a steady income. Some take what few teaching positions they can at colleges and universities – an increasingly unstable source of employment. Others land full-time jobs in the commercial arts. They set aside their own visions and projects in service of students and clients, while earning a salary that no doubt inflates the $43,230 median wage of U.S. artists reported in a 2011 NEA study. Offering limited opportunities for recognition and financial growth, these gigs can seem like consolation prizes in a field where few ever achieve stardom. However, for those artists lucky enough to make it big one day, the financial rewards can be enormous.

The arts labor market has been called one of the oldest examples of a “winner-take-all” economy, a term popularized by Robert Frank and Philip Cook in their 1995 book, The Winner-Take-All Society: Why the Few at the Top Get So Much More Than the Rest of Us. The hallmark of this kind of market is extreme income inequality, whereby a small number of the bright, talented, and fortunate generate the majority of economic value. Case in point: according to the New York Times, 56 percent of all concert revenue in 2003 flowed to just a handful of pop music stars like Justin Timberlake and Christina Aguilera. That left less than half the year’s proceeds to be divided amongst all other performers.

But the arts aren’t the only field in which a huge number of aspirants compete for few professional gigs, often choosing between what will sell and what they really want to do. Here we take a look at two other examples of “winner-take-all” economies and consider a future in pursuit of superstardom.

Fashion Models

In 2012, Gisele Bündchen earned $45 million. In addition to working her typical modeling gigs, the Brazilian thirty-something is a spokeswoman and endorsement queen contracting with big name brands such as Pantene, Esprit, and Versace. Her commercial success and business savvy have made her the Andy Warhol of the modeling world, although he never made nearly as much while alive. Gisele leads her supermodel pals in yearly earnings by a cool $36 million, with Kate Moss in distant second place.

Supermodel Gisele Bündchen reportedly earned $45 million in 2012. Photo credit: Tiago Chediak

The allure of such multi-million dollar salaries, the jet-set lifestyle, and the promise of beauty immortalized on the cover of Vogue has inspired many young women to pursue a modeling career. Popular TV shows like America’s Next Top Model have steadily increased the number of new hopefuls into the industry. Unfortunately, that has only made the dream harder to attain. Ed Razek of Limited Brands puts into sharp perspective just how tough it is to be one of 140 women to have strutted the catwalk for Victoria’s Secret over the years:

“There are seven billion people on the planet. That makes each of them not one in a million, not one in five million, not one in ten million. That literally makes them one in 50 million humans.”

All Bündchens aside, success in the fashion world is extremely difficult to attain. In fact, the median income for an American model in 2009 was $27,330. How is that possible? According to sociologist and ex-model Ashley Mears in her book Pricing Beauty: The Making of a Fashion Model, the sheer number of women competing for modeling opportunities today has caused pay rates to drop. A few years back a runway show would typically pay $1,000 to $5,000 a day. At this year’s New York Fashion Week, one model made between $800 and $1,000 per show and sometimes was only compensated in trade such as clothing, jewelry or makeup. She was also expected to front the expenses for her transportation to and from gigs, as well as for hotel stays. After all that, her agency still took a commission. A model can quickly find herself in debt if the jobs don’t line up – and they very well might not. It’s common for a model to go weeks without another opportunity. So why does she suffer through it all? For the exposure. Sound familiar?

Just like artists, models will often spend their own money on projects and ply their craft for next to nothing for the sake of exposing their work to a broader audience in hopes that they will eventually be “discovered.” If that moment never comes, the model may have to find a more reliable means of support. These jobs are usually less glamorous than shooting couture magazine spreads in exotic locations. In Pricing Beauty, Mears identifies the highest earner at one New York agency: a perfect size 8 who can charge $500 per hour for fittings with major American retailers. For all the cash she brings in, there’s little prestige in this type of work and agencies actually frown upon these jingle-makers of the fashion world.

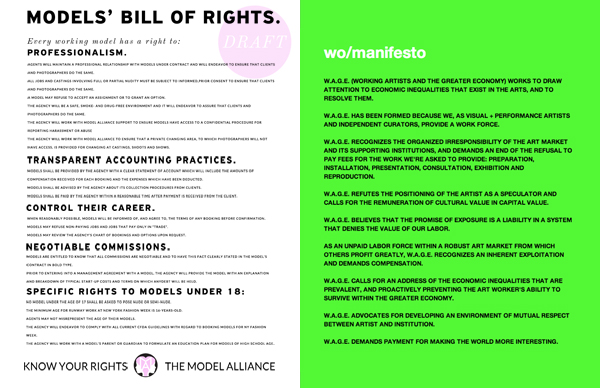

The Bill of Rights (left) drafted by Model Alliance and W.A.G.E.’s “wo/manifesto” both advocate for fair pay and ethical treatment of industry workers.

Not all models are willing to accept current wage inequities within the industry. Model Alliance is an unofficial union formed by supermodel Sara Ziff that aims to establish ethical standards and fair pay for its workers. Their interests mirror those of labor advocates in the arts, such as Working Artists and the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.), a New York-based group fighting for regulated payment of arts workers at nonprofit institutions. While both industries remain wholly unregulated, these labor organizations give voice to an under-paid and under-represented workforce. Which brings us to…

Lawyers (the curveball)

Practicing law has long been touted by many a family member as one of the most lucrative, and therefore reliable, careers. However, a shift in economic climate and rise in digital technology and information access has eroded this old standard. Once upon a time in 2008, recent law graduates had a job placement rate of 76.9% in positions that required passing the bar exam. Since then many changes have swept the industry, including automation of once labor-intensive work, the outsourcing of mid-level clerk positions, an increase in price competition, and a trend towards doing away with the billable hour structure. Last year, the American Bar Association (ABA) reported that barely half of law school graduates had found work in comparable full-time positions. Couple this high level of unemployment with the enormous amount of debt incurred by students—the average is about $125,000 for private law school—and the situation starts to seem a little desperate.

Andrew Carmichael Post, a “boy-genius” who passed the California State Bar at the age of 22, still wasn’t exceptional enough to land a job with a firm after graduating. He resorted to living with his parents, wearing Goodwill, and working four jobs as a computer programmer while taking on small business clients just to afford his $2,756 monthly loan repayment. His total debt of $215,000 far exceeds the national average. Post is not alone in having to adjust his career expectations. Above the Law recently stumbled across a job post on Boston College Law School’s website with an annual salary of $10,000. Not only is that below the minimum wage, it contrasts starkly with the $6,500,000 earned by the highest paid general counsel in 2012 – and that figure doesn’t include his stock option. Incidentally, the law office that posted the listing defended the low salary, citing “valuable experience” as a perk of the position. Thirty-two hopefuls applied.

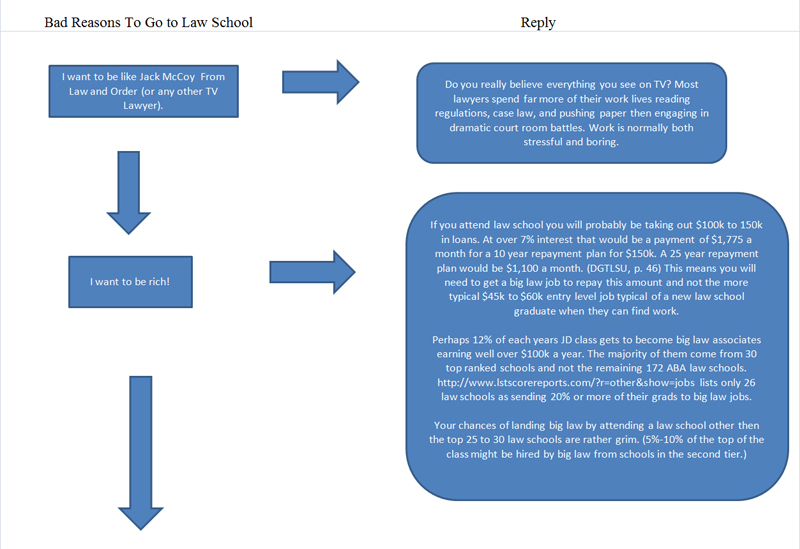

Detail of “Bad Reasons to Go to Law School,” an epic flow chart created by attorney Samuel Browning based on the book Don’t Go to Law School (Unless) by Paul Campos.

The legal industry has begun to respond to the changing shape of the marketplace. The ABA recently presented a report calling for education reform that would help reduce the time investment needed to obtain a law degree and promote lower tuition costs. It suggests training non-legal professionals in limited services and lowering requirements for taking the bar exam. Some law schools have already reacted by reducing class sizes. One has even lowered acceptance standards in an attempt to boost admissions after a drop in enrollment. A number of schools have opened nonprofit law firms to give graduates a little income and real world experience, while also addressing a growing need for affordable legal services. Dozens more plan to offer similar programs for alumni in coming years.

It’s uncertain whether changes within the legal field are here to stay, but for the moment they threaten to upend the lawyer’s traditional career trajectory from student to clerk to firm associate. They also hint at a future with more affordable basic legal services provided by lesser-paid specialists, while the talented and ambitious few in Big Law continue to command eye-popping salaries. Reflecting on the results of the 2013 Law Firms in Transition Survey, Tom Clay of Altman Weil wrote, “Firms are beginning to think more strategically about growth – trading up to improve profitability, rather then bulking up to drive gross revenues.”

Artists (home plate)

The rise of nonprofit law firms provides an interesting comparison to the arts. What would happen if arts schools now examined the law school model of running spaces where alumni gain experience, earn income, and provide a service to the community? Would this model temper dreams of art world superstardom and promote a more sustainable career path? Would it also provide a means of lowering education costs for artists, an issue the arts sector has debated heavily as more and more artists enroll in MFA programs, some with tuitions of nearly $100,000?

Many of those artists, just like Andrew Carmichael Post and his classmates, will likely have difficulty repaying their student loans. In “Artists in the Winner-Take-All Economy,” sociologist Mark Stern surmises that income disparity in the arts is representative of overall trends in our society, and we ignore it at our own peril. He also paints a rather pessimistic picture of an economy that perpetuates the culture of superstars ad infinitum once it takes hold. The outcome is a country wholly divided by income and accessibility, a depressing thought. However, if the arts are in any way representative of the rest of the system, then working to transform its micro-economy into a healthier and sustainable one may provide clues as to how to pull our society out of the superstar spiral.