(Jackie Hasa week at Createquity continues with the first entry in Jackie’s two-part series on games and the arts, likewise dating from Jackie’s time as a Createquity Fellow in the spring of 2012. Enjoy! -IDM)

The idea of using games as a new way to engage audiences has gained immense traction in the last 5 years. The museum world in particular has seen a great deal of discussion on this topic, from Nina Simon’s dozens of posts to this year’s Museums and the Web conference; these conversations are a natural outcropping of a much larger discussion about games in our everyday lives. I’ll be writing more about games in a later post, but I hope this one serves as an introduction to why this dialogue is happening now and what is at stake for the arts.

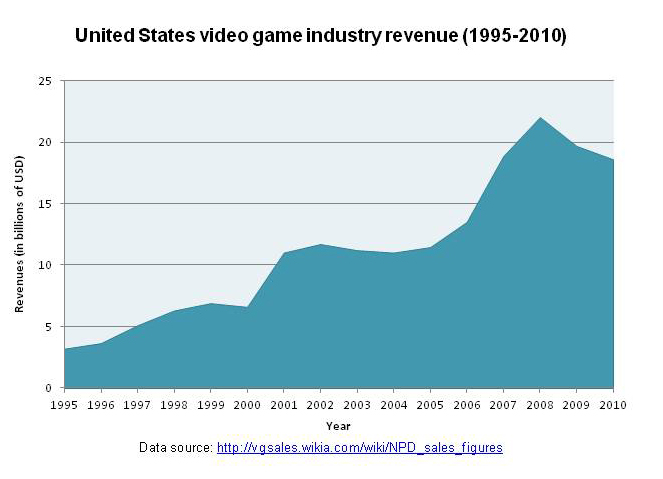

So why is everyone suddenly talking about games? Put simply, the immense growth of the video and social gaming industry is inspiring innovators across many sectors to ask how they might hitch themselves to this rising star. In 2011, video and computer games became the U.K.’s biggest entertainment sales category at 40.2% of the market, beating out music and video. The Entertainment Software Association notes the following staggering statistics about the 2010 U.S. market:

- Consumers spent $25.1 billion on video games, hardware, and accessories in 2010.

- 72% of U.S. households play computer or video games.

- 42% of all game players are women. In fact, women over the age of 18 represent a significantly greater portion of the game-playing population (37%) than boys age 17 or younger (13%).

- In 2011, 29% of Americans over the age of 50 played video games, an increase from 9% in 1999.

Note: Sales numbers provided here include console and PC sales only; the $25.1 billion sales total for 2010 provided by the Entertainment Software Association includes a broader range of video/online games.

The implications of this data extend far beyond the screens that limit video games to the virtual world—their newfound cultural ubiquity means that huge numbers of the population can now more easily recognize tropes and imagery from video games in real-world settings. The tools of the online gaming world (getting points for accomplishments, ascending in level, unlocking achievements, and participating virtual social circles) have become powerful ways to engage an audience for any organization, whether an arts nonprofit or a private company. Foursquare is just one well-known example of this phenomenon, as participants receive points and other rewards for visiting a particular venue in real life.

Academics and game designers have generated a number of theories about the power of these kinds of games. Jane McGonigal, probably the most visible representative of this cohort, has made a name for herself arguing that games can literally make the world a better, happier place by harnessing their power in the service of solving real-world problems, from bodily injury to oil shortages. In his review of her recent book, Reality Is Broken, Ian Bogost argues that games allow for engagement with real-world problems by providing complex modes of inquiry rather than clear solutions. Finally, folks like Jesse Schell imagine a terrifying future in which nearly every activity we undertake is part of a game in which we accumulate points via specially-designed sensors. These are powerful ideas, and they are continuing to gain traction as technology allows for the omnipresence of games in our lives through smartphones, ultralight computers, tablets, wireless internet, and even Schell’s toothbrush sensors.

While games can clearly serve numerous social, educational, or marketing goals, the debate over whether they might form a legitimate arts genre rages on. Roger Ebert famously thinks not, and undoubtedly not all games should be considered art, since most are created primarily as products to be sold to a mass audience. However, more and more institutions are placing at least certain kinds of games on the art pedestal. In just the past few years, Georgia Tech has co-hosted an Art History of Games conference, the Computerspielemuseum (Museum of Computer Games) opened in Berlin, and the Grand Palais in Paris hosted the Game Story exhibition; in May, MoMA will host a program titled “The Game as an Art Form.” This proliferation is rooted in games’ fundamental resemblance to conceptual art in which the audience, or player, is integral to the work. One can cite a range of work in this vein, including Yoko Ono’s instructional Grapefruit, Allan Kaprow’s performances, a great deal of the art produced for Burning Man, and Punchdrunk’s ongoing Sleep No More production. Other pieces like Manchester street artist Filthy Luker’s playable Space Invaders installation pay more direct homage to popular games.

Filthy Luker’s Space Invaders installation. Credit: Duncan Hull.

Arts organizations stand to gain a great deal from refining their relationship to video and real-world games. As games industry growth outpaces already-recognized art forms like music and video, institutions should certainly incorporate games into a larger marketing or audience engagement strategy to stay relevant. But beyond that, arts organizations can positively affect the trajectory of games in culture through serious investment in programs like commissions, residencies, or cross-sector collaborations. When music and video became dominant entertainment forms, they were embraced and challenged by artists willing to push the boundaries of popular practice, and arts institutions can and should encourage the same evolution in games.