(Our weeklong celebration of Createquity’s Jackie Hasa concludes with the second installment of Jackie’s analysis of the role of games in the arts. This entry explains why so-called “gamification” is weak tea when it comes to exploring the true potential of interactivity, and offers a number of suggestions for how arts organizations can make better use of the principles of gaming in their programming. -IDM)

In my first post on games and the arts, I wrote that the massive growth of the video games industry in the last 20 years is motivating the integration of game dynamics with all sorts of products and services. While games that take place in the real world have a long history (e.g. sports, board games), new forms are emerging as the lines between our online and offline lives continue to blur. A number of arts organizations are considering mobilizing games in the service of increased ticket sales, improved audience participation, and outreach to new audiences, but these so-called “gamification” efforts typically fail to take advantage of games’ full potential for creativity. This post provides a few paths forward for organizations interested in really delving into this rich world. Good games are hard to make, but done well, they can help arts organizations achieve their missions—and help them rewrite the rules for audience engagement.

Gamification: Scratching the Surface

Gamification refers to any system that uses game design elements in a non-game context, usually to encourage some desired real-world behavior like participation in market research or the achievement of health goals. In essence, gamification takes an act usually valued for its intrinsic qualities—play—and exploits it for an instrumental purpose. Its proponents claim to be able to make a game out of literally anything, a powerful idea that understandably excites arts organizations looking for new, innovative business models. Because instrumentality fundamentally defines gamification, though, these schemes can result in an experience that isn’t really very fun or engaging. For instance, the Brooklyn Museum’s tagging game to crowdsource collection indexes might help it organize its objects, and the Sydney Festival’s scavenger hunt-style mobile app might help its attendees navigate their offerings, but neither use game mechanics as more than a thin veneer over experiences that may (or may not) already successfully engage participants. Ultimately, many uses of gamification are as superficial as credit card rewards programs; cultural critic Ian Bogost has even suggested the name “exploitationware” to critique gamification’s more addictive qualities and removal of any expectation of actual play.

There’s nothing wrong with arts organizations using points and other game rewards as part of a toolkit to boost attendance, reach fundraising goals, or solve a host of other potential problems. However, those sorts of programs don’t take advantage of the intrinsic qualities of games that encourage creativity in players. In The New York Times, Sam Anderson quotes Frank Lantz, the creator of the iPhone game Drop7, describing why gamification doesn’t tap into games’ full potential as works of art in their own right:

He said that real games are far too fragile and complex to be engineered by corporations and that their appeal goes much deeper than reward schedules. “It’s as hard to make a really good game as it is to make a really good movie or opera or hat,” he told me. “Sure, there’s mathematics to it, but it’s also a piece of culture. The type of game you play is also a part of how you think about yourself as a person. There’s no formula that’s going to solve that equation. It’s impossible, because it’s infinitely deep and wonderful.”

Complex, well-executed games intrinsically provide both structure (in the form of rules) and the creative freedom to experiment (as participants explore ways to win through play). As experiences, they are playful, interactive, and also provoke participants to think through unfamiliar systems—a characteristic that runs directly counter to the mindless quality of most gamification efforts and aligns games more closely with challenging artworks. Games can be immersive, aesthetically interesting experiences that investigate many of the same sociological, cultural, political, and formal questions more traditional artists address. By investing in games for their intrinsic rather than instrumental qualities, arts organizations can serve their missions in a fresh way while engaging audiences primed to reflect on more commercial gaming experiences they’re likely already having. Fortunately, the broader culture of gaming provides plenty of fodder for an organization looking for models beyond compulsive point rewards.

New Game Subgenres and What They Can Offer

A number of relatively new subgenres can provide inspiration for game experiences that allow audiences to play as creative agents. Below, I’ve provided a short list of subgenres along with examples of how an arts organization might use them. As with any new project, the target audience should drive an organization’s decisions, since they hold varying levels of appeal for different groups.

- Role-Playing Games (RPGs) have their modern roots in Dungeons & Dragons, which was first published in 1974. These pen-and-paper games are essentially interactive fiction, in which the players determine the story collaboratively. To do so, players take on different roles and powers defined by the game master as s/he interprets the gaming guide, a set of rules defining the fictional world they inhabit, challenges to overcome, and possible player actions. The game evolves as players take turns, accomplish tasks, and interact with the fictional world. Video games that require players to choose an avatar as part of a fantasy or science fiction story are often based on tabletop RPGs. They have also given rise to the live action role-playing game (LARP), a theatrical variation that takes place outside the home and often involves elaborate costumes and battles with fake weapons.

- Why an arts organization might create one: By taking on specific roles, audiences can engage with complex histories or present-day cultural landscapes. For instance, players at a museum could become artists in a particular collaborative (like the Bloomsbury Group) and create alternate histories of the artists’ work and lives through gameplay. A theater group could include well-known local performers as roles in the gaming guide—and then invite those performers to participate in the game by acting as the game master. RPGs tend to be most rewarding to play when participants feel welcome to riff on their roles, so organizers need to be willing to cede control of the game narrative to the players.

- Alternate Reality Games (ARGs) are related to RPGs, and are similarly characterized by a fictional narrative. However, ARGs cultivate a deeper suspension of disbelief because they tend to take place over many weeks, and gameplay is interspersed with more everyday, “real world” activities rather than being governed by a text-based guide. Plots are often cloaked in mystery, and designers tend to run things from “behind the curtain.” In an ARG, instead of turning the page to find out what happens next, players must solve puzzles or find clues hidden in the real world, which then unlock communications from (often virtual) fictional characters that move the plot forward. ILoveBees is one of the most famous examples of this sort of game.

- Why an arts organization might create one: Among other things, ARGs can take people all over cities to solve puzzles and perform different tasks, scavenger hunt-style. They can be useful if an organization would like audiences to visit partner venues, and demonstrate connections between disparate places or ideas through the ARG narrative. Because of the fictional plot, ARGs are also an opportunity for organizations to tell a story—it just has to be engaging enough that audiences want to discover the next piece.

- Blended Reality games take integration with the real world a step further. Rather than focusing on the fictional “layer” over reality, in blended reality games, the game world is our world, and play takes place without the intervention of characters or invented plot devices. Games like SFZero (which I have worked on) define themselves more as an “interface” for the player’s city than an alternate reality.

- Why an arts organization might create one: These sorts of games have similar applications to ARGs, but don’t necessitate the creation of a fictional world. Rather than veiling the gameplay in a custom-made fictional plot, designers use our everyday fictions and symbols to color the game. In Paul Ramirez Jonas’s Key to the City, participants used keys to unlock dozens of doors throughout New York (many of which were at museums), endowing the normally symbolic gift of city keys with real-world consequences. Blended reality games can help arts organizations encourage participants to think critically about their everyday behavior in a more explicit way than an ARG.

- Augmented Reality Games use the camera, tilt sensor, GPS, and accelerometer features in handheld systems to interact with real world conditions. Players can kick a virtual soccer ball through their iPhone camera, or fight other players for territory using a GPS map of their locations.

- Why an arts organization might create one: Depending on the audience, arts organizations may prefer to use technology to spur engagement in a game, and the use of smartphones can allow participants to play anywhere, in a much more casual way than most of the other game types listed here. Following the ARstreets graffiti game example, arts organizations could create augmented reality games that allow players to reimagine already-extant murals, change the marquees of concert halls, or design a building for an empty lot. The augmented reality game can be viewed as a genre unto itself, but it’s also possible to integrate augmented reality features into other types of games. For instance, in an alternate reality game, rather than finding physical clues in a gallery, a player could simply hold up his or her phone to the space and reveal a message hidden virtually. Creating a system that works well and offers substance beyond a “cool” tech factor would require a significant investment of resources, though.

- Serious Games engage with the real world through the lens of a particular pressing problem. As with Jane McGonigal’s World Without Oil, these games often use elements of ARGs and crowdsourcing techniques to engage players to find solutions for in-game problems that hopefully have implications for the real world.

- Why an arts organization might create one: A film festival presenting a particularly political series of documentaries might like audience members to gain a better understanding of the problems presented by working to solve them. Serious games can be created to find solutions to any problem, but engagement often depends on finding a sufficiently compelling problem and framing it well. Serious games can also cross the line into gamification if their design relies too heavily instrumental tools like adding up points and achievements, and less on intrinsic qualities like player imagination and interactivity. For example, American Public Media’s Budget Hero gamifies balancing the federal budget in a closed, virtual setting and has successfully garnered over 6,000 comments. If those commenters could work collaboratively toward their budgets, or in a more open-ended way, a different, less gamified experience would result.

- Big Games or Street Games tend to eschew heavy use of technology or fictionalized narratives and (as the names suggest) bring together masses of people to play in public spaces like streets, parks, or malls. Big game designers often borrow heavily from playground games like tag, hide-and-seek, or scavenger hunts, but view the site-specificity of the city environment and act of playing as an adult as potentially transgressive. Because these games usually necessitate the presence of an organizer or referee, they tend to take place in festival format, as exemplified by IndieCade, igfest, and Come Out and Play (which I work on in San Francisco).

- Why an arts organization might create one: These sorts of games are often cheap to produce, and work nicely with a lo-fi maker/DIY aesthetic. They can help transform socially rigid spaces like galleries, theaters, or offices, but may work less well if a more polished experience is intended.

In addition to how a genre fits with a particular need, arts organizations should also consider playability and the nature of engagement in the game. These qualities define the game’s mood and level of accessibility, and help shape the game to a particular audience.

Playability. Playability might seem like an intrinsic characteristic of any game, but a spectrum exists here as well, as many games prioritize abstract aesthetics and concepts over lived player experience. Penn & Teller’s Desert Bus video game, in which players must drive a bus in real time from Tucson to Las Vegas—a journey that takes eight hours and cannot be paused—intentionally eliminates as much actual play from the game as possible. Many gamified activities also deemphasize play, though in the service of chosen outcomes rather than art. Some ARGs and LARPs focus on the fictional narrative over play.

Nature of engagement. The nature of engagement indicates the sorts of activities a player must undertake to play the game. These can range from the simple and easy to learn, as with Foursquare (just go somewhere and check in), to The Jejune Institute, a months-long ARG that required players to visit multiple sites around San Francisco, listen to a special radio station in Dolores Park, and obtain information from street performers, among other tasks.

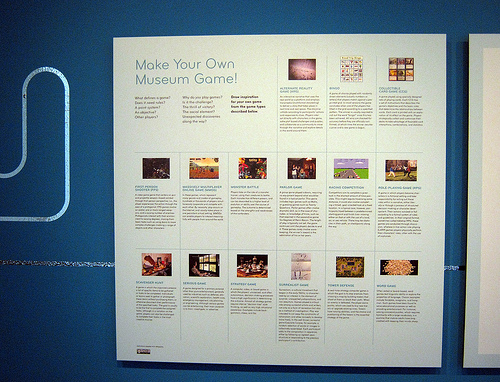

Experimenting with Games – SFMOMA’s ArtGameLab and Beyond

SFMOMA’s current ArtGameLab exhibition offers a fantastic sampler of many of these sorts of games in a museum context, created in part to “break down institutional barriers to experimentation by providing new models for presenting multi-vocal, crowd-sourced content.” While a step in the right direction, the art museum’s own “institutional safeguards” prevented a completely untamed game experience (and curator Erica Gangsei certainly recognizes as much). The exhibition lives up to its claim as a “lab,” posing questions about how games can work within a large institution.

Labs are fantastic, but more fully realized game programs are the next step. While participatory art and activities of all kinds are slowly making their way into organizational settings, games represent an even deeper way to embrace contemporary, less hierarchical definitions of art. By offering an alternate set of behavioral rules, games present an opportunity for audiences and institutions to revise those that govern the presentation and consumption of art. Through games, organizations can rewrite what an arts experience really is, and recognize that changing the rules doesn’t have to be so scary.