It seems that you can’t read an article about New York City in any news source, whether it’s Gawker or the New York Times, without hearing the buzzword “gentrification.” But what do people mean when they toss this word around and how does it look to the people living in affected areas? Why do people draw a connection between artistic hubs and gentrification? Though gentrification is a catch-all term used to describe a range of interrelated outcomes, it is generally connected to changes in an area’s culture and character, demographics, the real estate market, and land use. Due to a long history of rampant racial inequity in U.S. housing and public policy, the term is also closely associated with a larger idea of “a miscarriage of social justice, in which wealthy, usually white, newcomers are congratulated for ‘improving’ a neighborhood whose poor, minority residents are displaced by skyrocketing rents and economic change.”In recent years, two neighborhoods in New York City, Crown Heights and Harlem, have undergone dramatic physical, cultural and demographic changes. Both neighborhoods are attracting new residents along with businesses that cater to their tastes. You only have to walk down the streets of either these two neighborhoods to see that the process of gentrification is well underway, if not almost complete. In recent months, New York Magazine and the New York Times have published articles about the city’s reinvigorated real estate market, especially in areas like Harlem that even ten years ago were still seen as areas that needed civic investment and redevelopment if they were to appeal to mainstream middle- or upper-class tastes.

The massive transitions taking place in Harlem and Crown Heights are just as closely tied to economic status as they are to race. Sociologist Sharon Zukin defines gentrification as a process of spatial and social differentiation that results from the influx of educated, middle-class people into low-income areas. The form of urban gentrification seen over the last half century differs from previous incarnations because of the type of cultural capital these new urban dwellers bring with them. The new agents of gentrification seek out the same characteristics that made previous generations flee urban areas, namely distinctly urban attributes like diversity, walkability and historic significance. While these new urbanites may not always be economically well-off, they are drawn to the aesthetics of what they see as the “authentic” city, but inevitably their surroundings are eventually molded by their own presence.

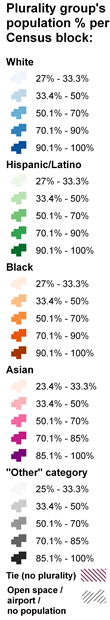

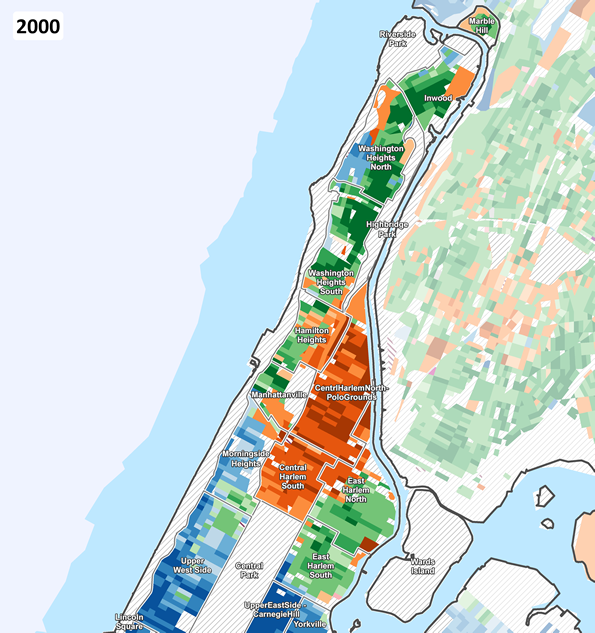

Watching the process of gentrification unfold in New York City may be an opportunity to learn from arts-based community revitalization efforts in places like Watts, CA; Houston, TX; and Chicago, IL, and give policymakers, practitioners and residents an opportunity to envision an inclusive future for their community. Although both Crown Heights and Harlem have experienced an exodus of many of their black residents, blacks still maintain a tenuous plurality in most parts of these neighborhoods, indicating that while there is a threat of increased displacement, there may also be opportunities for those remaining to take an active part in the reshaping of their communities. Will Crown Heights and Harlem fall prey to the oft-discussed negative consequences of gentrification? Or is there still opportunity for these neighborhoods to retain a connection to their original inhabitants?

Why Crown Heights and Harlem?

Both Harlem and Crown Heights (and more broadly, Brooklyn) have their own cultural currency tied to a heritage that has dominated much of U.S. popular culture over the past twenty years. These neighborhoods are synonymous with defining artistic movements in black culture like jazz and hip hop, art forms that have had a global impact. The connection these two neighborhoods have to cultural milestones such as the Harlem Renaissance and the early work of Spike Lee attracts new residents eager to build upon the past and contribute to a new phase of development in their own way.

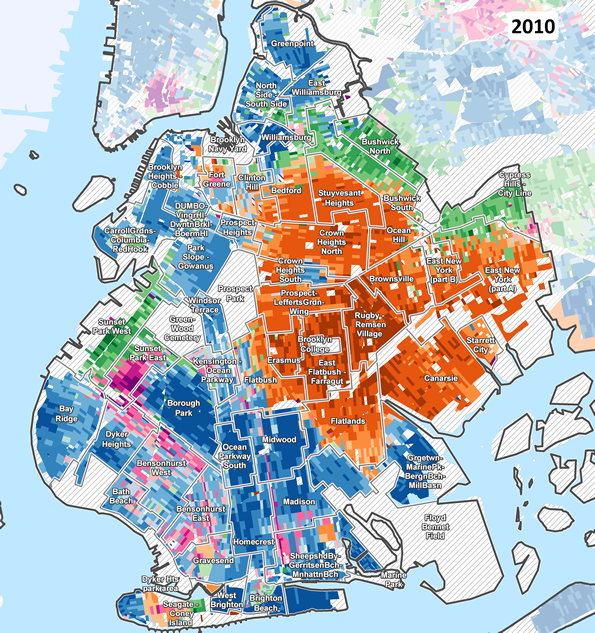

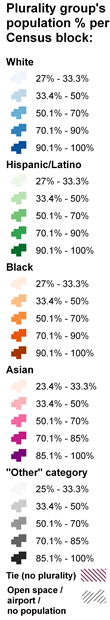

Brooklyn racial demographics, 2000, courtesy of the Center for Urban Research at the CUNY Graduate Center

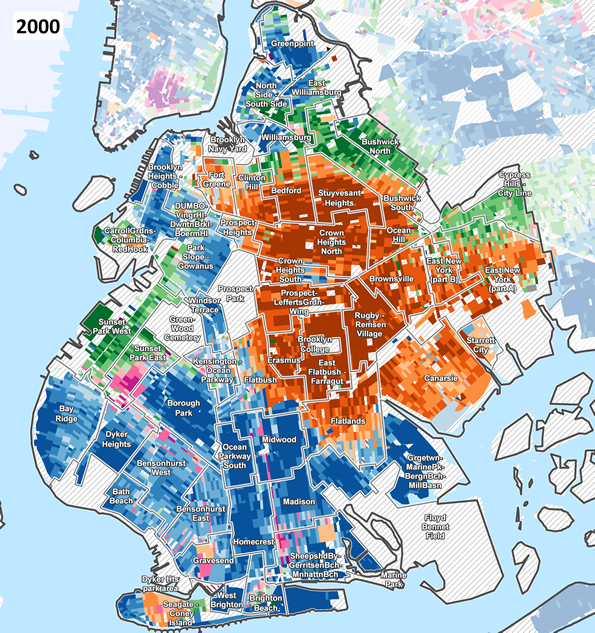

Brooklyn racial demographics, 2010, courtesy of the Center for Urban Research at CUNY Graduate Center

In spite of the fact that more and more young white New Yorkers are moving to the neighborhood of Crown Heights, a majority of residents are distinctly not part of the wealthiest tier of society. Crown Heights is not the kind of place like Williamsburg or DUMBO that gets highlighted in discussions about the new wave of New York’s vibrant arts scene. There is plenty of existing grassroots arts activity from practicing individual artists, community based organizations, and community-based arts projects, it is still difficult for local cultural organizations based in Crown Heights to garner enough funding and support to work with under-resourced communities, with dueling priorities like crime and education. That said, the changing demographics of the area, as well as its proximity to attractions like the Brooklyn Museum and the Barclays Center and the resulting increase in real estate value, has attracted the attention of traditional and untraditional creative placemakers.

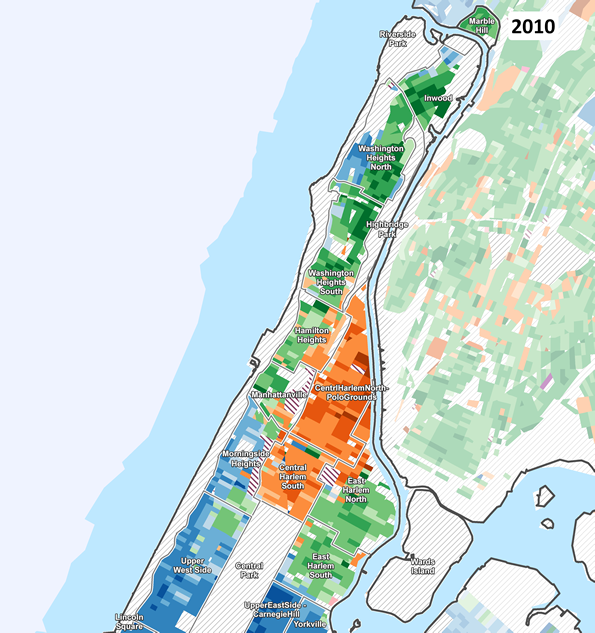

Upper Manhattan racial demographics, 2000, courtesy of the Center for Urban Research at CUNY Graduate Center

Upper Manhattan racial demographics, 2010, courtesy of the Center for Urban Research at CUNY Graduate Center

Although Harlem has a more well-established cultural brand and presence than Crown Heights, it too is becoming a hub for creative industry and the creative class, albeit in a different form. Tour buses constantly drive through Harlem, giving visitors a chance to view iconic landmarks like the Apollo Theater or visit the Studio Museum in Harlem. Over the past three years, Harlem has gained two independent multi-use creative arts spaces, MIST and ImageNation, started by long-time Harlem residents or advocates. These organizations are helping to shift the perception that change in previously distressed communities has to come from the top down. Instead, they demonstrate that culturally-based organizations can uplift and strengthen the creativity that already exists in a mutually beneficial way.

For all of the discussion of gentrification and displacement, it seems that many authors and researchers approach the issue from the frame of high-income whites displacing low-income people of color. What happens when high-income people of color become part of the process of redevelopment and reinvestment? The presence of MIST and Imagenation in Harlem highlight the nuanced dimensions of gentrification and confront misconceptions about what the process entails, who the drivers are, and how established residents play a part in the redevelopment of their neighborhood.

What Role Does The City Play?

Entire books have been written about New York City’s public policy, city planning, and their relationships with the arts and gentrification. Today’s New York has a unique relationship with gentrification because the constant hunt for refuge from the city’s high cost of living, paired with the city’s concentration of wealth, makes for some combustive elements.

In September 2008 the New York Times ran a brief update on a redevelopment project, titled Mart 125, which would include 67,000-square-foot space for a cultural and commercial complex across the street from the Apollo Theater. Mart 125, an urban revitalization plan originally conceived nearly 20 years earlier in 1986, encountered delay after setback after delay until the Bloomberg administration issued an RFP to reinvigorate the project in 2008. As the Times article notes, arts organizations that met a threshold of financial stability and community involvement would get preference in the process of becoming a selected tenant. One of the selected occupants of this space was ImageNation, a small nonprofit arts organization whose mission is to “establis[h] a chain of art-house cinemas, dedicated to progressive media by and about people of color.” As part of executing that mission, the organization sought to create a gathering space for the community that could also serve as an affordable visual and performance arts venue.

Headed by Moikgantsi Kgama, a long-time Harlem resident with roots in the independent filmmaking community, ImageNation had been searching for a permanent home for its frequent events almost since its inception in 1997. The organization and its staff needed the room to expand and live up to its goal of becoming a go-to place for art-house cinema. In a recent interview Kgama noted that Mart 125 seemed to be the perfect opportunity for ImageNation to capitalize on the growing community reinvestment in Harlem. By the turn of the 21st century the more commercial aims of Mart 125 were coming to fruition, with new outposts of Starbucks, H&M and American Apparel opening up on the strip of 125th Street between Frederick Douglass and Malcolm X Boulevards. The city and its various development agencies seemed poised to make good on their commitment to provide space for local cultural organizations. ImageNation and other organizations were strengthened by the rigorous RFP process and collaborative relationships with various city agencies, which asked them to meet tough benchmarks related to fiscal and organizational management to equip them for long-term success. Then the 2008 financial crisis descended upon the nation, the city’s priorities shifted and the community-based arts organization focus of Mart 125 stalled. Kgama and the staff of ImageNation remained determined to develop space in Harlem, along with other organizations like My Image Studio Theater Harlem (MIST). Both organizations opened space in Harlem in 2012, years after Mart 125 had come to a virtual standstill.

Today, MIST and ImageNation join a cohort of creative organizations run by people of color that are contributing to Harlem’s legacy as a creative hub for the city. These organizations are intentional about how they fit into the community and what role they should play in Harlem’s artistic ecosystem. Not surprisingly, they appear to be embraced wholeheartedly by the community’s new and old residents. ImageNation not only screens films and provides gallery space for up and coming artists, they also host engaging community events such as an attempt to create the world’s longest Soul Train Line, in honor of Don Cornelius, and to draw attention to Mental Health Awareness month.

In May of 2012 the New York City Economic Development Corporation issued a request for construction bids to resume redevelopment and attempt to continue on with the Mart 125 project. In spite of the delays with the city-sponsored community redevelopment, it seems that these community based organizations have been able integrate themselves into the neighborhood in ways that respect the integrity of Harlem’s long cultural history while contributing to the neighborhood’s evolution. Would these organizations have been established in their current forms without the push for gentrification and development from the city? It is hard to tell. What is clear is that ImageNation and other local arts organizations have been able to capitalize on the interest in the “new” Harlem in order to gain access to the space they need to serve their community.

What Role Does the Private Sector Play?

In Crown Heights, the connection between gentrification and creative placemaking has been driven more by private sector dollars than by civic investment. Crown Heights is not connected to a specific cultural moment like the Harlem Renaissance, but it is increasingly being cited in articles about gentrification in New York City. Though there are established organizations in the community that use the arts as part of their programming, Crown Heights has attracted two large-scale creative placemaking projects that have met very different fates. While one has received a large amount of private financing derived from sources outside of the community, another, a brainchild of Crown Heights residents, has floundered.

Brooklyn’s recent resurgence as a cultural destination has been buoyed in part by the various enterprises of Jonathan Butler, creator of the website Brownstoner and co-creator of the very popular Brooklyn Flea. In 2012 it became public that Butler and his business partners were planning a large-scale development project in the heart of Crown Heights. The project being proposed is a mixed-use development that will provide space for artists and food vendors from the Brooklyn Flea to create and sell their wares. Unlike his contemporaries in Harlem, Butler epitomizes what many envision when they think of gentrification: white, wealthy, and attracted to the “potential” of under-resourced neighborhoods. Through his personal connections to Wall Street, Butler was able to raise seed capital from Goldman Sachs to fund his newest venture. This has given Butler and his partners the freedom to “seek input and support” from city agencies and politicians, without being completely dependent upon bureaucratic maneuvering to complete the project. Instead of the drawn-out process that stalled Mart 125, Butler has been able to close on this $30 million project and is already in talks with potential tenants. Contrast this with the experience of the small arts organizations in Harlem, or the more recent attempts of a group of artists in Crown Heights who have been unsuccessful thus far in their attempts to purchase a building in the area for a similar purpose as Butler and his partners.

Although Butler has been able to breeze past the bureaucratic red tape and ecure space for his tenants, long-term residents of Crown Heights are wary of the project, seeing it as a harbinger of higher rents and changing demographics. Indeed, Crown Heights has had a high influx of white, upper income residents according to the 2010 census. There are also few signs that Butler or his private sector partners are looking at this as an opportunity to engage the diverse communities currently living within Crown Heights. On the day Butler announced the building purchase, Brownstoner posted a publicly available survey of potential tenants asking where interested businesses and business owners were currently located. However, questions about race or income levels, which would directly speak to the economic and social tensions that this project uncovers, remain unasked. In more recent reports it appears that tenants will be handpicked by Butler and his investors, maintaining continuity with the brand his previous ventures have established, regardless of how that affects the current community.

According to Ms. Kgama of ImageNation, it is difficult for small arts organizations that are led by or serve people of color to succeed because they often don’t have the fiscal backing or stability to compete for larger funding opportunities. At the same time, as Kgama points out, in rapidly gentrifying areas “it helps” for the organization to be led and staffed by people of color, so long as it is reflective of the surrounding area. Although there are a diverse range of experiences within every ethnic group, more often than not organizations led by people of color are more responsive to the wants and needs of minority groups, thereby making their host communities more receptive to their presence.

This also suggests that instead of a top-down approach, the needs of the community will be reflected in the programming showcased by the “gentrifying” organization. So far MIST and ImageNation seem to be embraced because their leaders made a conscious decision, reflected in their mission, to be reflective of and responsive to the cultural legacy of their host communities. It remains to be seen if Butler will take an inclusive approach to his new project, or if he is even concerned with avoiding perception as a malignant gentrifier. If he is, there are a few organizations in Harlem that he can ask for tips.