This is the first piece in a three-part series on the tragedy of the commons and what it means for the arts sector.

Remember that group project you had in middle school where one of the members slacked off and got the same grade as you? What about that green stuff growing in the back (and maybe event the front) of your fridge in college? Sometimes, when a group of people is collectively responsible for a thing or an action, members of the group don’t do their part–leaving the project unfinished, or the refrigerator unclean.

Arts funders and policymakers are often shooting for goals that require on-the-ground organizations to work together. The Surdna Foundation, for example, “supports efforts that provide artists with business training and financial resources that enable them to be, and create, valuable economic assets for their communities.” One of the grants Surdna has made under this program is to the Rebuild Foundation, an organization that helps finance cultural spaces. This is an important effort, and it is a major part of “providing artists with…financial resources,” but it alone does not make financial resources and business training available to all artists. Instead, the Rebuild Foundation works within an informal network of organizations in St. Louis, Omaha, Chicago, and Detroit to help make the arts a more viable livelihood and to stimulate local economies by strengthening the arts. The strategies that Surdna and all other grant-making institutions put in place have implicit, if not explicit, theories of how the organizations they fund will work with others to reach the goal the foundation intends, e.g., viability of an artist livelihood.

Goals that require a shared purpose, as the goals of many foundations do, are not all that different from those you and your roommates had in college of keeping the fridge clean. Under certain circumstances, they can be left unmet. An understanding of some of the perspectives on why that happens and how to prevent it can help improve the outcomes of a foundation’s strategies.

Tragedy of the Commons

The most common answer to why shared goals are left unmet draws on an out-of-date example about which most people today know very little: common grazing land. Using the metaphor of common grazing land for all shared goals and resources goes back to ecologist Garrett Hardin’s 1968 article in Science, “The Tragedy of the Commons.” In it, Hardin asks us to picture an open pasture. He argues each herdsman in town has the same incentive: to bring all their cows to this free grazing land. As more and more cows come onto the land, a threshold is passed beyond which the shared land is degraded and becomes unfit for grazing. He explains that typically we expect the invisible hand of the market to help us move toward a better society—competition weeds out the socially costly and leaves us with the socially valuable firms and products. In this case, the invisible hand of competition has led to the degradation of what was a perfectly good pasture. Hardin goes on to extrapolate this to other problems like pollution. Each potential polluter faces higher benefit than cost from polluting, so each chooses to pour their leftover grease into the sewer. Hardin calls all of these shared resources or goals “the commons” and names the overconsumption of them “the tragedy of the commons.”

Tragedy of the Jam Session

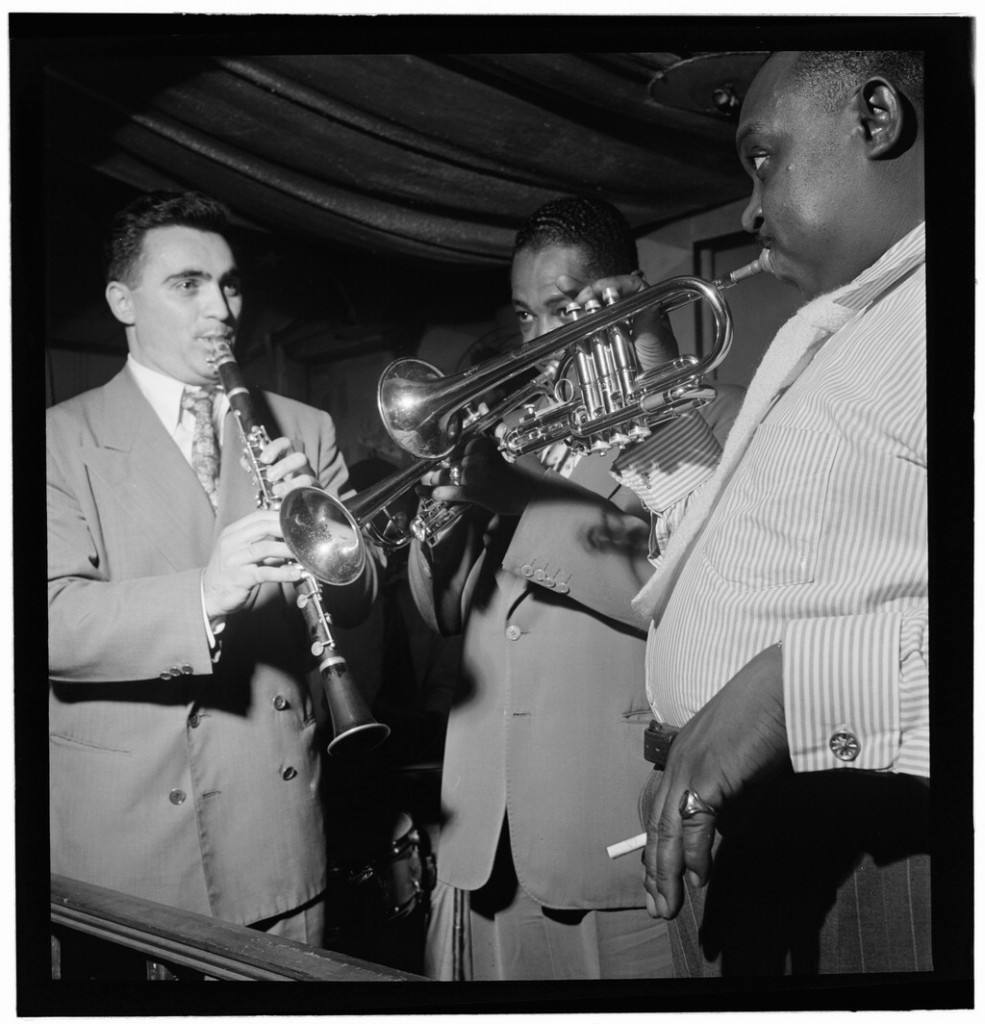

This same problem can arise in the arts on a micro-level. Take, for example, a simple jazz jam session.

In a smoke-filled room in the West Village, four up-and-coming bebop players take the stage. They’ve never played together before, but they’re pretty talented, so the audience is expecting a show. Each player wants to live up to that expectation; she hopes that everyone in the room enjoys the music, and that she herself will enjoy it too. At the same time, each member wants to show off her chops with some improv. Improvisation is limited to one player at a time in most bebop settings, and if it runs on too long in a context like this, it can ruin the tune.

Each player, then, has two main incentives: to play the song well together and to take more improv time than the other members. Playing the song well is a goal that all members share responsibility for meeting. Every member looks bad if the song flops. If the song sounds great, everyone has succeeded. Assuming the tune as a whole sounds good, each member can make herself look better by playing a solo that is a little bit longer.

The first soloist begins as the melody ends, and she faces each of these incentives. At this point, the band is playing well together, and it doesn’t seem like playing a little bit longer than normal will mess up the song too much, so she chooses to play one extra time through the chord changes. The player who follows faces the same incentives, and also chooses to improvise longer than necessary. Likewise for the third and the fourth soloist. Three-quarters of the way through the tune, the audience is texting and checking email–they came to hear jazz, not a bunch of overly-eager youngsters play worn out licks over the same tune for an hour. The shared goal that they set out to meet has gone unmet, and each member of the band looks worse because of it.

Making Tragic Grants

Individual arts organizations competing for grants are faced with a similar set of incentives as the herdsman or the soloist. A greatly over-simplified, but illustrative example may be helpful here:

Two organizations have a goal. This goal is something like providing a community and audience exposure for emerging artists and cultural innovators. Each organization uses this mission to define metrics and targets for success and measures performance by attendance and the number of performances held in a given year. Both organizations share a similar mission and constituency, so they look for funding from the same foundation.

Meanwhile, the foundation from which they are soliciting funding is attempting to meet its own mission of making the broader community a hub for cultural innovation. Let’s say it also believes that attendance and the frequency of performances are critical components of success, and it chooses to emphasize these metrics in the grant-making process by giving only to the best-preforming organization.

If both arts organizations know the metrics that the foundation is using for assessing potential grantees, they will compete to host the performances that will be most likely to draw the largest, most consistent audiences. A problem arises because an organization can win the funds by scheduling performances that directly compete with the other organization’s schedule, drawing away potential guests on an important night for their competitor. Similarly, one of the organizations can lose out on the funds if they attempt to develop new artists that will benefit the community-wide goal of innovation rather than attempting to bring in established, highly demanded performers. No organization is made better off by focusing on the broad shared vision; they are only made better off when they focus on the part of that vision that can be attributed immediately to their work. In this way, the shared vision of cultural innovation is lost to the competitive struggle for funding.

For the jazz quartet discussed above, multiple internal and external forces set incentives. The arts organizations’ incentives, on the other hand, are at least in part set by the foundation’s expectations for how the grant money will be used and what it will accomplish. Foundations thus have a responsibility to understand how the incentives they create promote or hinder cooperation between grantees.

Avoiding the Tragedy

If you’ve ever had a clean refrigerator, seen a good jazz jam, or observed organizations with competing incentives reach a common goal, you already know instinctively that the tragedy of the commons is not a necessary evil. People and organizations find ways to solve problems like these every day. Anthropologists, economists, sociologists, political scientists, and ecologists have attempted to draw general lessons from people world-over who maintain working commons. In the next installment of this series, I will explain how their theories might work in the situations described above.