The U.S. has now entered an era of extremely expensive sports stadiums: the new Barclays Center in Brooklyn, NY cost a cool billion dollars for example,while the new Vikings stadium in Minneapolis, MN is anticipated to be similarly priced. While reading up on the professional sports billion dollar building boom I couldn’t help but notice a number of parallels to the building boom in the arts from 1994 to 2008, as studied and documented by the University of Chicago’s Cultural Policy Center.

But does new and big automatically lead to better for an organization and its patrons? For a large renovation or construction project to succeed, certain parameters and rationales have to be put in place from the beginning, such as a clear connection to the mission of the organization and strong, continuous leadership throughout the life of the project. Yet time and time again, it seems that these large capital campaign projects are launched without any adherence to methodologies that have previously led to success.

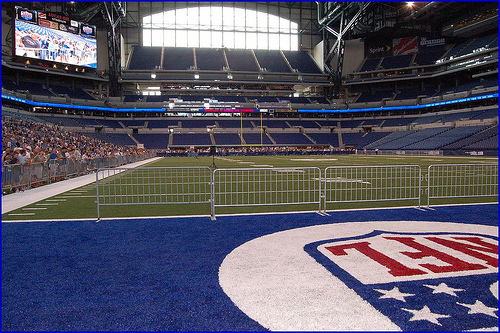

As Dane Stangler points out at Growthology, renovations to old stadiums or the construction of brand new stadiums often result in more costs than benefits for the communities in which they are housed. These new, large-scale projects come with promises of low real expenses to local governments, as with the stadium in Indianapolis which officials promised could be paid for through a negligible tax hike. In fact, cities often construct generous, even risky, debt structures in order to help underwrite these structures, despite the fact that there is not a definite assurance of profit, or even repayment. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution notes that “unrealistic revenue projections and the skyrocketing construction cost of sports stadiums, especially football behemoths, is making it increasingly hard for the facilities to generate enough cash to keep pace with expenses, namely debt service.” This can result in higher ticket prices, higher taxes, and depleted services for consumers and non-consumers alike. Stangler notes that public subsidization of stadiums often shifts costs from wealthy owners and players to visitors and tourists, who may not even be visiting the city for sports-related reasons.

In spite of the obvious negatives, legislators and franchise owners argue, perhaps rightfully so, that they need state-of-the-art space to attract talent and remain competitive. That argument sounds awfully similar to those made by nonprofit arts organizations when they decide to undertake expansion projects. New buildings, like Taubman Museum of Art’s new facility, come with enormous costs and can force already cash-strapped organizations to take on more debt and risk the sustainability of the entire organization.

During the boom years, many museums and cultural institutions wanted to take advantage of the deep pockets of their big donors and take on large infrastructure projects. According to the University of Chicago Cultural Policy Center study cited above, this led to significant “overinvestment during the building boom—especially when coupled with the number of organizations that experienced financial difficulties post-building.” Much like their for-profit counterparts, cultural institutions were overly optimistic about the positive returns their efforts would have—yet four-fifths of the projects studied ran over budget, often by significant amounts. This type of development will often alter the business plan for the expanded institution to pay for the increasing expenditures and higher operating cost. However, the consequences for arts organizations that overextend themselves are often much more dire than for NFL teams that generate billions of dollars in revenue. When is the last time you heard of a sports franchise closing up shop because it was no longer able to sustain itself?

That said, there are examples of cultural institutions that manage an expensive physical expansion and resulting fundraising campaign in ways that not only benefited the organization by helping it to further execute its mission and better serve its constituents. One example cited by the Nonprofit Finance Fund is the Steppenwolf Theater in Chicago, IL. Part of the reason the Steppenwolf has been able to sustain itself in spite of a large real estate purchase is that the institution understood that the real estate itself would not be the main income generator. Instead, as the organization grew physically, it sought out diverse revenue streams, from individual contributions to corporate giving, in order to support this expansion.

At the end of the day, professional sports generate a huge amount of revenue from a variety of sources (broadcast rights, apparel sales, concessions, ticket sales, etc) and public officials are dazzled by the dollar signs–in 2012, professional sports leagues generated roughly $24.7 billion in revenue. That is with one league being on strike (the National Hockey League) and not playing games for most of a season. Many are desperate to get a piece of that fiduciary pie by whatever means necessary. By contrast, the power dynamic is flipped when it comes to cultural institutions; they have to pitch the value of investment and advertising to their funders, not the other way around. I believe this is why cultural institutions are often left “holding the bag,” scrambling to cover the cost of ambitious expansions as opposed to sports franchises, who are often able to walk away from fiscal disasters of their own making.