(Anne Gadwa Nicodemus is one of the smartest people I know and a nationally-recognized expert on creative placemaking and artist spaces. Currently principal of Metris Arts Consulting, she is a choreographer/arts administrator turned urban planner, researcher, writer, speaker, and advocate on the intersection of arts and community development. Please enjoy her guest post tackling one of the most controversial topics in our field – artists’ role in gentrification. -IDM)

Impetus

“Artists as the ‘shock troops of gentrification’.”

That’s a quote by art historian/critic Rosalyn Deutsche included by Creative Time in a recent email invitation to its upcoming summit on the “contributions and complicity of culture in the development of 21st century urban space.”

And here’s an excerpt from Project for Public Spaces’ article, “All Placemaking is Creative” published last month (emphasis mine):

Placemaking…is a vital part of economic development. And yet, there has long been criticism that calls into question whether or not this process is actually helping communities to develop their local economies, or merely accelerating the process of gentrification in formerly-maligned urban core neighborhoods. We believe that this is largely due to confusion over what Placemaking is, and who “gets” to be involved. If placemaking is project-led, development-led, design-led or artist-led, then it does likely lead to gentrification and a more limited set of community outcomes.

Project for Public Spaces is a NYC-based nonprofit that advances placemaking (without the creative modifier). Its article makes a few good points, most importantly that placemaking should be an inclusive process and that there is not a singular “community,” but rather, pluralistic communities. But I winced when I read its damaging mischaracterizations of artists’ roles in placemaking, which ironically undermine its call for inclusivity. It implies that artists’ place at the community development table comes at the expense of other voices being heard. I got the sense that it dismissed artists as privileged others, as opposed to the “regular people” who should be shaping placemaking processes. It seemed to lump artists with developers and planners in terms of power and clout. All are harmful mischaracterizations.

The PPS article and shock troop quote propelled me to coalesce some of the thoughts that have been swirling around my head about why we perceive artists as gentrifiers, where those bleed into misperceptions, and how to learn from both.

The Bigger Picture

It’s a new phenomenon for artists to have a place at the table of community development. The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and ArtPlace have, collectively, invested $41.6 million in creative placemaking projects in just two years. This is an impressive amount of resources and the momentum is exciting. However, it’s still a drop in the bucket when one considers all of the dollars for community and economic development in this country. By way of comparison, in 2010 and 2011 the federal government invested $240 million in just one grant program (HUD Sustainable Communities). Happily, in 2011 HUD took the unprecedented step of including arts and culture in Sustainable Communities grants, one result of the creative placemaking frame. But consistently considering arts and culture within community development efforts is still far from common practice.

The scars of redlining, blockbusting and urban renewal still shape what neighborhoods look like, who lives where, residents’ access to good education and employment, and what homes are worth. The fates of swaths of neighborhoods are out of residents’ hands; banks have foreclosed on large percentages of properties. Sketchy lending and a demand for mortgage backed securities means ownership is not vested with the people living there, but rather with countless remote and untraceable investors who own “toxic assets.” Cozy sweetheart deals between politicians and developers, forged in the name of economic development, are still common. When land-use decisions do include public participation, middle-class homeowners and whites are more apt to show up and speak up at meetings than low-income renters and people of color. Non-English speakers are often forced to rely on impromptu translators or aren’t even in the room because the announcement flyer wasn’t in their native tongue. These are the kinds of placemaking inequities we should challenge and change, instead of turning artists into scapegoats.

When we talk about issues of power, social inequities, or “the politics of belonging and (dis)belonging,” as Roberto Bedoya so eloquently frames, I want us to remember that artists, on average, have low incomes, and that they are not all white. The NEA’s Artists and Arts Workers in the United States (2011) reveals that musicians, dancers and choreographers, photographers, and other entertainers’ median salary is under $28,000. Despite artists’ high levels of educational attainment, the average salary for all artist occupations (including architects) is just over $43,000. Over twenty percent of artists are racial/ethnic minorities. And these statistics are only for people for whom being an artist is their “primary” job.

We have an unfortunate tendency in the U.S. to view artists as special/different/other. Larry Gross likens it to artists being on a reservation or special island in his On the Margins of Art Worlds. As early as elementary school, teachers single out a few students with god-given talent from the apparently uncreative masses. This is a cultural construct. In Native American cultures, art is an integral part of life, not a separate vocation/occupation. In their Native Artists: Livelihoods, Resources, Space, Gifts (2009), Markusen and Rendon point out that there is no word for art in Ojibwe or in many tribal languages.

One wonderful role that artists play in dominant U.S. culture is that of the provocateur, and for that, yes, they do need a bit of distance to see things and make critical commentary. But that certainly does not mean they are by default elitist, snobs or more creative than thou. They are of the community. They are some of the regular people that proponents of inclusive placemaking, like PPS, should wish to involve. They happen to have unique skill sets and when they’re game to apply them for the common good via placemaking, we should embrace and nurture their efforts.

The Antitheticals

Hennepin Avenue Re: Model led by visual artist Ta-coumba Aiken as part of Plan-It Hennepin’s Creating Urban Visions workshop. Photo by Mark Vancleave, 2012.

Recently in Minneapolis, I witnessed how a team of artists from Tom Borrup’s Creative Community Builders used movement, song, writing exercises, and sculpting to draw out participants’ visions for Hennepin Avenue. The “regular” people at the meeting both seemed to have more fun and contribute richer and more nuanced ideas than I have witnessed in typical community planning meetings. The planning process for the cultural district also harnessed teenagers’ creativity. It empowered them to canvas the avenue to suss out public space (and its absence), interview people, and document through video.

As executive director of the Tucson Pima Arts Council, Roberto Bedoya puts his money where his mouth is—supporting projects consistent with his public call for more emphasis on issues of social inequities within the creative placemaking policy rhetoric. In the Finding Voice program, for example, refugee youth generate stories and images through print publications and art projects at the mall and bus stops. These forms of expression help make their lives visible and affirm their place in Tucson’s civic fabric. In another example, artist/architect Bill Mackey worked with dozens of collaborators on Worker Transit Authority. In an exhibition of mock planning projects created by a mock planning authority, Tucson residents engaged in three weeks of dialogue on issues of land use, infrastructure, and transportation.

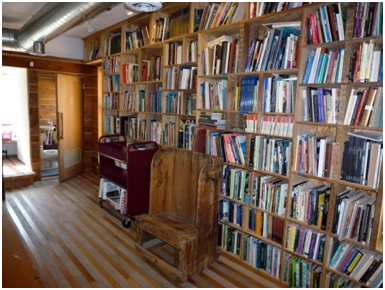

In the Dorchester neighborhood of Chicago’s South Side and increasingly in cities across the country, Theaster Gates asks impertinent questions about the way things are and invents alternatives—he calls it art, and gatekeeper establishments like MOCA (Los Angeles), the Whitney Biennial, and Armory Show (New York) agree. He turned an abandoned two-story house into a library, in part to thumb his nose at city officials who claimed there weren’t enough resources to expand that level of services into the neighborhood. He looks for and exploits all the tie-ins and synergies he can find. Black Cinema House, for instance, converts a small abandoned Dorchester home into a neighborhood space for screenings and conversation. Master builders and educators employed local residents in the deconstruction of the old space, providing job skills. Black Cinema House will also ultimately provide live/work space for film-and media-based artists of color.

The artists involved in these kinds of initiatives are deeply motivated by concerns for social justice and equity. They often come from the neighborhood they seek to benefit or other strong ties may fuel their commitment.

The Agnostics

Other artists have no interest in placemaking at all, and that’s also a completely valid choice. They may be traditional object makers or present works of theater, dance, or music in conventional venues. Those works of art also bring society joy and beauty; they inspire us or make us question f***ed up stuff.

Some artists might rehab a building as a studio or residence, because they just need an affordable place to live and work. They spruce it up and add value. They may be good neighbors, but have no interest in opening up their homes and workspace for frequent community events.

Untangling Culpability

But the role of artists as gentrifiers is, unfortunately, deeply entrenched in our collective popular imagination. People intuitively feel artists are attracted to down and out neighborhoods and can invest sweat equity, money, and artist juju into properties. They’ve heard about the SoHo effect and how artists are often victims of processes they set into motion; they get priced out of the very neighborhoods they helped to turn around.

Through my work, I’ve learned that it’s not so simple. Since the 1970s, thousands of American and European urban neighborhoods have been gentrified without artists involved, often by developers, often with public funding, chiefly to young professionals and to suburban retirees wishing to live in the city. Ann Markusen points out that gentrification is a function of generalized pressure on urban land markets—i.e. in NYC, every rich person in the world has to have an apartment—and that it does not occur in most small towns and in urban neighborhoods in vast portions of many cites.

Here are some of the ways the story varies in cities with weak real estate markets. In Lowertown, St. Paul, I documented artist space initiatives that spanned a fifteen-year period and were part of an overarching affordable housing strategy. I found few red flags for gentrification-led displacement beyond dislocating vagrants that sheltered in the abandoned buildings themselves. The neighborhood is more racially and ethnically diverse than before the artist spaces, and, for better or worse, still has quite high poverty levels. In Philadelphia, Mark Stern and Susan Seifert have documented fascinating community benefits that occur from “cultural clusters” (or concentrations of cultural participants, nonprofit arts organizations, commercial cultural firms, and resident artists). They find that these neighborhoods have higher levels of civic engagement, increased population and housing values, and decreased poverty rates, with little evidence of ethnic displacement.

Even with the most notorious example, SoHo, the story is more complicated than artists suddenly making the area have cachet and driving up prices all by their lonesome. In her seminal Loft Living, Sharon Zukin maps a system of government officials and real estate and banking interests. She tells the story of how they turned to live/work zoning and marketing of the bohemian lifestyle as a profitable way to deal with under-utilized industrial buildings and attract middle-class individuals to the area.

The Co-opted

As the SoHo example suggests, even though “shock troops” is an overstatement of artists’ roles in gentrification, pawns may not be. The perceived link between artists and gentrification is one reason that mayors, developers, and business improvement districts “buy” creative placemaking’s potential. The policy architects behind creative placemaking have been pretty transparent about their implicit goals of attracting such non-traditional arts stakeholders to invest in arts and culture.

The merits of silo-busting aside, I have serious qualms about artists being co-opted within creative placemaking projects. Particularly as advanced by the NEA (but also by ArtPlace), creative placemaking emphasizes cross-sector partnerships. Within NEA-funded projects, an arts or cultural organization always participates, but they may not be the lead partner. Even within arts organizations, administrators far removed from artistic processes may drive institutional involvement. Unfortunately, I’ve seen the line item for artist fees get cut before other project expenses when projects faced budget constraints. Artists are used to coming to foundations and city officials as supplicants, with outstretched hands, palms up, often unaware of their value. They certainly do not rival developers in terms of political savvy or financial capital. These power imbalances permeate partnerships and collaborations. Though creative placemaking initiatives can and often do empower artists, they also run the risk of paying lip service to artist involvement or worse, even using them for nefarious purposes like the exaggerated “shock troops” of gentrification claim that has caught hold of our collective imagination.

Questions and Crossroads

How do we grapple with these issues of agency, voice, and power? Change hinges on powerbrokers, the elites—sometimes merely in that they can obstruct it. How do we prevent their active involvement from silencing, or co-opting, artists and other vulnerable or marginalized populations? How do we make sure these interests are central to placemaking efforts?

Creative placemaking encompasses a broad array of practices, and as a field we need to drill down and examine initiatives that resulted in expanded opportunities for low-income communities, people of color, and artists against those that had undesired affects of displacement. How do different types of interventions correlate with outcomes? Is displacement just a by-product of generalized pressure and larger macro-forces in the economy?

Within the realm of artist space, is artist-ownership a remedy? Artists’ equity stakes do not safeguard against neighborhood change. Even in the celebrated example of the Paducah Artist Relocation Program (KY), many artists cashed out during the economic downturn, jeopardizing its claim as an artist haven. Are models of nonprofit ownership and stewardship, such as Artspace’s, the benchmark? In those, low-income artist tenants have long-term stability, but no equity. However, the building’s artist character and affordability is retained in the long-term. To ensure that a mix of housing options remain for families with modest incomes, do artist space initiatives need to be combined with non-arts affordable housing strategies? What can we learn from land-trust models? Maria Rosario Jackson’s Developing Artist-Driven Spaces in Marginalized Communities: Reflections and Implications for the Field offers some wonderful insights that advance thinking and practice.

I repudiate the notion that artists are the shock troops of gentrification. Artists are, however, on a different front line. They are looking hard at issues of their potential complicity in gentrification. They’re some of the most thoughtful voices grappling with questions of social equity in placemaking. Through nuanced practice, they’re “making the road by walking,” to quote Myles Horton. Instead of casting stones, our challenge as a field is to listen deeply and amplify these voices.