Can food be art?

Image courtesy of Jacquelyn Strycker

Last night, I cooked broccoli rabe with caramelized onions and vegan fennel sausage, along with a creamy parmesan polenta and a crusty whole wheat rosemary bread made from the Camaldoli sourdough culture that I feed flour to each day. Like many artists I know, I love to cook. My bookshelves are filled with equal numbers of art books and cookbooks. I often spend between one and two hours making dinner each night. I used to feel guilty about this—worried that my time would be better spent in my studio drawing or printing or otherwise artmaking—but then I came to see that making food—combining textures, flavors, scents and colors—is also creative. Indeed, I know many artists who are also passionate about food, and have come to consider food a part of their practices. A recent New York Times opinion piece even claims that food “has replaced art as high culture.” Yet the same article argues that food is not art.

Proust on the madeleine is art; the madeleine itself is not art.

A good risotto is a fine thing, but it isn’t going to give you insight into other people, allow you to see the world in a new way, or force you to take an inventory of your soul.

Is this true, or do chefs deserve a place at the table with painters, sculptors, photographers, musicians and performers? Can food be art?

In fact, there’s a long tradition of food as artistic medium. A paper by Howard Coutts and Ivam Day published by the Henry Moore Foundation describes the European sugar sculpture, porcelain and table layouts from the 16th through 19th centuries. Dining was not just about eating food, but also about its elaborate display. Tables were adorned with sculptures made from marzipan, wax or sugar paste. Court artists and designers “of the highest caliber” were the creators of these edible works. Coutts and Day describe an 1815 feast given in the Great Hall of the Louvre by the Royal Guard to celebrate the final defeat of Napoleon:

Huge pièces montées, in the form of gilded sugar military trophies, crafted by the patissier Carême, were displayed between the tables. At this level, table decorations were an aspect of political and social prestige, and required the skills of the finest artists and craftsmen of the time.

More recently, we can look at German artist Wolfgang Laib’s milkstones and rice pieces. Laib’s milkstones are large square slabs of marble that have been hollowed out and filled with milk, resulting in reflective white squares. His “Unlimited Ocean” was a grid of 30,000 piles of rice installed at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Laib uses these natural materials to create ephemeral and sensual experiences.

Similarly, we can also look at the work of emerging artist Leah Foster, who has created elaborate installations using cupcakes. For Muffin Tops, she used thousands of cupcakes and glazed surfaces of the gallery with batter and frosting.

But food as medium is not the same as declaring that a meal is art. We get closer to this with relational aesthetics and social practice, which often use food to facilitate social interaction and community. Last year, Rirkrit Tiravanija replicated his installation, Untitled (Free/ Still) at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Museum goers were able to enter a gallery and receive a bowl of vegetarian thai curry over rice, take some water from a stocked refrigerator and then sit at one of several communal tables. The work was originally installed at 303 gallery over 20 years ago. The artist describes the original installation in a conversation with MoMA’s Director, Glenn Lowry.

So when you first walk in, what you see is kind of haphazard storage space. But as you approached this you could start to smell the jasmine rice. That kind of draws you through to the office space. And in this place I made two pots of curries, green curries. One was made how Thai restaurants in New York were making it. To counter that, on the other pot was a authentically made Thai curry. I was working on the idea of food, but in a kind of anthropological and archeological way. It was a lot about the layers of taste and otherness.

Fallen Fruit Collective is another example of participatory art involving food. David Burns, Matias Viegner and Austin Young use fruit as a material to explore notions of “urban space, ideas of neighborhood and new forms of located citizenship and community.” One of their most popular projects are their “public fruit jams” in which they invite members of the community to bring fruit and collaborate with one another to make jams. The collective explains:

Working without recipes, we ask people to sit with others they do not already know and negotiate what kind of jam to make: if I have lemons and you have figs, we’d make lemon fig jam (with lavender). Each jam is a social experiment. Usually held in a gallery or museum, this event forefronts the social and public nature of Fallen Fruit’s work, and we consider it a collaboration with the public as well as each other.

But ultimately the aforementioned projects are art first and food second. We don’t really care how Tiravanija’s curry or Fallen Fruit Collective’s jams taste; food is the means to creating a social work. Rather than art made from food (food as medium), or art that uses food to create an experience (food as impetus), is there art that is food that is art?

We start to get there if we look at small-scale food production. Community gardens are now often viewed as both organic, local food sources and art projects. Victory Gardens 2007+ is a project developed by Garden for the Environment and the City of San Francisco’s Department for the Environment with “lead artist” Amy Franceschini. Both an art project and a model/ support system for urban gardening, they’ve received funding from art institutions like SFMOMA and the Fleishhacker Foundation. The project aims to create a network of “urban farmers” who utilize rooftops, window boxes, backyards and unused plots of land for food production. It includes the development and distribution of seed starter kits to home gardeners, food-production educational initiatives and the development of a city seed bank. The success of the gardens and seed bank are integral to the success of the project, making it equally about art and food production.

If food production can be art, why don’t we also consider the cooking of food as art? Combining and transforming materials is a fundamentally creative activity, whether those materials are paints, clays, musical notes or edible ingredients. In fact, gastronomy is even included in some countries’ ministries of cultural affairs. The embassy of Peru’s Public Diplomacy department lists “gastronomy, including the promotion of the Peruvian national drink, Pisco,” in the six types of cultural programming that the embassy supports, alongside visual arts exhibitions, cinema and music. Last year, Spain’s Ministry of Culture partnered with Casa Asia, the Cervantes Institute and the Spanish Embassy New Delhi to promote Spanish “culture industries” in India. The programming included a lecture from José Luis Galiana of Basque Culinary Center, the first university-level education centre in Gastronomic Sciences in Europe. And, in 2010, The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) honored the “gastronomic meal of the French” as part of the “intangible cultural heritage of humanity.”

If cuisine can be recognized as culture, then why aren’t we also acknowledging it as art? At street fairs in Brooklyn and on etsy.com, handcrafted, small batch artisanal foods like habanero ketchup, black garlic mayo, buffalo jerky and sea salt chocolate caramels are sold alongside knit scarves, hand sewn quilts, embroidered tea towels and beaded jewelry. The most recent Renegade Craft Fair— a juried marketplace of handmade goods– had vendors selling items like letterpress stationary, molded soaps, screenprinted t-shirts, ceramics and carved wood furniture, as well as local honey, cookies, spices and bonbons, and offerings from Chickpea & Olive and La Crêpe C’est Si Bon. The DIY movement has embraced food as craft.

The design community has also begun welcoming cuisine into the fold. Core77 Design Awards includes a category for “Food Design.” The Vitra Design Museum Boisbuchet in France has hosted a lecture by food photographer, designer and cookbook author Emilie Baltz. And in 2011, I attended Talk to Me: A Symposium at MoMA, a program that featured presentations and panel discussions related to the Architecture and Design’s concurrent exhibition, Talk to Me: Design and Communication between People and Objects. Marcus Samuelsson, the acclaimed Ethiopian-born and Swedish-raised chef and owner of Red Rooster Harlem was one of the panelists. Samuelsson passed out spiced nuts to rapt audience members, and spoke about how he designed the menu at his restaurant so that it would reflect the diversity of the Harlem community in which it’s located: dishes include soul food and Dominican cuisine with nods to Samuelsson’s own Swedish heritage, all using foods from local farmers and artisans. He was both chef and designer.

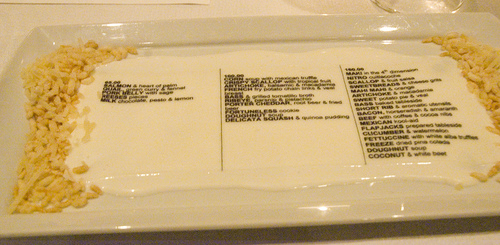

We can also look at molecular gastronomy as a point of intersection between design and food. Also referred to as modernist cuisine, it involves the application of scientific principles to cooking in order to create surprising and inventive aesthetics and textures in food. At Moto, a Chicago restaurant that specializes in this type of cooking, diners may be served a deconstructed/ reconstructed avocado, be asked to put on a smoked glove to eat a chocolate dish, and finish their meal with a printed elderflower-marshmallow menu. The restaurant’s kitchen includes a lab where chefs conduct technological experiments to create innovative dishes with flavors that often seem incongruous to their appearance, disrupting diners’ notions of what food can be.

The art world is beginning to notice. In October, Suzanne Anker, Chair of the BFA Fine Arts department at the School of Visual Arts, organized a conference called “Molecular Cuisine: The Politics of Taste” that investigated “the importance of taste from the perspectives of the culinary arts, sociology, art history and theory, anthropology, as well as the cognitive, material and biological sciences.” Anker’s projects at SVA include overseeing the creation of a Nature and Technology Lab, where, among other things, students can experiment with alternative growing systems like aquaponics, and a molecular gastronomy kit that gives them the tools to create items like olive oil foam, balsamic vinegar caviar and strawberry spaghetti.

But it shouldn’t just be novel high-tech cooking techniques that warrant our attention. The art world needs to include chefs like Marcus Samuelsson, Alice Waters, David Chang and Christian Puglisi in its conversation as well. Waters’s restaurant, Chez Panisse, opened over four decades ago with seasonal menus created from organic, locally-sourced ingredients, serving as a model and inspiration for the locavore and slow food movements. Her Edible Schoolyard Project, begun in 1996, integrates gardening, cooking and sharing school lunch into the academic curriculums of participating institutions. Chang’s Momofuku empire serves food that combines techniques from and pays homage to wildly varying fare including Asian street food, French cuisine and McDonald’s. Puglisi’s Relea is committed to providing creative, organic, environmentally responsible meals while simultaneously eliminating the exclusivity associated with fine dining. These chefs aren’t just cooking inventive and delicious cuisine. They are also using food to tell stories, conjure memories, and to establish philosophies, such as a connection between cooking, community and sustainability.

The arts, including painting, sculpture, installation, dance and music, are in part about creating a sensory experience—something for the audience to see, feel or hear. And perhaps more than any other discipline, food has the ability to appeal to all of our senses—a combination of colors, textures, crunches, smells and tastes goes into the making of a meal, and the selection and transformation of those elements is creative. When a creative, sensory form also has the capacity to express philosophies, inspire multiple interpretations, conjure narratives and/or allude to complex meanings, it is art, whether the medium is paint or piano or polenta. Food has not replaced art as high culture; it is art.