Nearly two months after its initial publication, the July-August Atlantic Monthly cover story, “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All” by Anne-Marie Slaughter, still has people talking (among them Steven Colbert and the listeners of the Brian Lehrer Show). The article details the author’s difficulties balancing a career as Director of Policy Planning at the State Department with her responsibilities as a mother. This reportedly became the magazine’s most widely read article, provoking a “firestorm” of responses from journalists and readers alike. These included critiques of its very title (did feminism ever promise women that they could “have it all,” vs. simply having choices?) and its presumption that “work-family dilemmas are primarily an issue for women” and not parents of both genders.

Despite these debates, critics do seem to agree that Slaughter makes compelling suggestions for policy changes to the “insanely rigid” American workplace culture “that produces higher levels of career-family conflict among Americans…than among any of our Western European counterparts.” Slaughter also makes some compelling recommendations for “reorganizing individual career paths to lessen that conflict.”

Like just about every other woman I know, I devoured all six pages of Slaughter’s largely personal narrative—but couldn’t help feeling less than satiated by a discussion mostly limited to traditionally cutthroat, male-dominated professions like corporate leadership, government and law (with academia offered as the main contrast). The perspective of women who work in my field, the arts, seemed notably absent.

I grew up with the presumption that a woman artist could “have it all,” with my own mother, Eleanor Cory, as my role model: a new-music composer who was very involved in my and my sister’s lives while continuing to write music (and get it performed and recorded), landing a tenured college teaching job in NYC, and winning competitive residencies and grants. She has always told me, “It’s a very creative thing to have kids. It made my music better.”

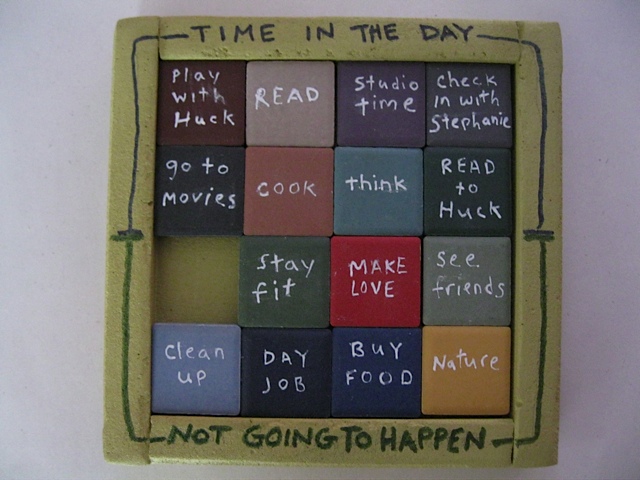

Yet many childless artists I’ve encountered in my generation seem to struggle to reach a situation similarly conducive to raising a family and earning a living without sacrificing creative passions. I’ve frequently heard artists say things like, “How does one juggle a day job + an art practice + babies? Art is already my baby.”

To gain additional perspective, I interviewed a number of artists I know who are also mothers, and perused parenting blogs geared towards musicians, artists, and writers. (While I was preparing this article for publication, Artinfo published a similar investigation by Alanna Martinez with a focus on “high-achieving women in the [visual] arts,” including leaders of several major institutions. My interviewees, by contrast, included practicing artists at various career stages in both the visual and performing arts. They offered more extensive suggestions for specifically balancing art-making and family, not only work and family. They also generated more ideas for tailoring existing artist support structures more towards parents.)

I was pleasantly surprised to find that many of these artists believe that the arts sector is more female- and family-friendly than, say, a top post in Washington D.C. Yet “having it all” in the arts can nevertheless take tremendous dedication, organization, and luck.

Below are some of the most common and compelling points from our conversations.

The path to “success” for an artist is open to interpretation

Anne-Marie Slaughter discusses women’s fear of “falling off the ladder” and missing out on positions of power in fields like politics, business, and law, due to children.

By contrast, according to installation artist Caitlin Masley, “how an artist defines success is relative to the artist.” Masley, with Dannielle Tegeder, is co-founder of Momtra, a blog for artists with young children that contains helpful hints for maintaining work-life balance, a list of successful, well-known artists who are also mothers, and myriad personal accounts. Says Marilyn Minter in the Artinfo piece, “The art world is difficult whether you have children or not. I’ve seen some women become better artists when they had children. Now they had to succeed!”

I spoke with one composer/PhD student who believes there may be risk in scaling back work to start a family, but asserts, “If that means my music won’t be played in the biggest concert halls by the most prestigious groups, that’s fine—I know my work will still be appreciated and performed.” Nevertheless, she believes that the art world’s “obsession with youth” (as evidenced by the number of award programs in her field for artists under 30) drives many artists to wait until their early or mid-30s to start a family, after gaining some career recognition. Artists who do make this choice are likely to face the greater risks associated with having children later in life (an issue addressed by Slaughter in her piece).

The importance of flexibility and time management

Slaughter believes the mainstream American workplace should provide more opportunities for employees to set their own schedules and work from home. She discusses the relative ease of motherhood when serving as her own boss, prompting her decision to return to her tenured professor position at Princeton after two years in Washington.

The approximately 60 percent of artists that are self-employed (according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics) should, by Slaughter’s definition, be in the ideal position to be parents. Most artist-mothers I interviewed did indicate that the ability to work out of home studios, and plan work time around naps and bedtimes, is indispensable. Performing artists needing to take jobs dependent on others may have a harder time; however, a blog post in Paste Magazine, 18 Musical Moms Talk Motherhood, is full of stories of female band members bringing babies on tour.

Slaughter also discusses the importance of shifting the American workplace culture to one that values working fewer hours but more effectively. Several artists with young children described being brutally strict about time: for example, squeezing in an hour of “writing time” right after a child’s bedtime, in the words of one testimonial on the Momtra blog. My mother believes that “less time to work means clearer faster decisions, greater intensity and commitment, elimination of unnecessary activities.”

Despite greater job flexibility, artists must navigate a three-way balancing act: parenting, working to earn money, and making artistic work that does not necessarily earn money.

Patricia Runcie, actor, director, theater producer and teaching artist (and mother of a 16-month-old) explained, “Often to work on an artistic project doesn’t make any financial sense. However, as an artist, you have this compulsion to keep working…So even when unpaid/low pay opportunities come up, you want to take them.”

In addition to missing out on benefits like employer-provided health care and maternity leave, artists I interviewed who are piecing together part-time work also described challenges like having to rehearse and perform in spaces with no breastfeeding accommodations.

Jeanne Quinn, visual artist and single mother of a one-year-old, is extremely grateful for her university tenured job in Colorado: “I had a semester of maternity leave at full pay…Nobody in the US has this…and I know exactly how lucky I am.”

Like Quinn and Slaughter, my mother attributes much of her successful balancing act to good academic jobs.

Every artist I interviewed mentioned the importance of hiring (and the challenge of paying for) help to watch children even when working from home–“the only way to get work done,” as one put it. One artist exclaimed, “Sometimes it doesn’t even make sense for me to take paid jobs instead of staying home because if I’m not home all the money I earn goes to childcare.” Many artists I interviewed cited the far better childcare and family leave systems in other countries, particularly in Europe—an observation backed up by the American Sociological Association.

The art world could still use an attitude shift

Slaughter believes that “While employers shouldn’t privilege parents over other workers, too often they end up doing the opposite, usually subtly, and usually in ways that make it harder for a primary caregiver to get ahead.”

I will never forget when one of the artists in the 11-month-long residency program I coordinate waited almost nine months before even mentioning her eight-year-old daughter. Though our program welcomes artists with families, she described being told in the past by other galleries not to mention it “or people won’t take you as seriously.”

Actress/director Runcie described having to pick and choose the productions (“largely organized by people who know me and the value of my work”) willing to accommodate her parenting schedule. “As a theatre artist (especially an actress),” she said, “I find there is this attitude in the industry that there are a million more of us out there, so if I have kids and it might be a ‘problem,’ they’ll just go with the other girl…I keep my family life very secretive unless they’ve worked with me before.”

Rebecca Hackemann, a British multimedia artist and mother of two school-aged children, states, “There seems to be a prejudice in the art world, that once you become a ‘mother’ you are no longer hip, cool and fascinatingly eccentric.”

Not every artist I interviewed reported such dilemmas. Quinn and Masley both described positive experiences in galleries with sympathetic curators (especially those who are also mothers). Said Quinn: “[My infant son] and I did four big installations this year, and his pack-n-play was set up in the middle of the gallery every time when we were installing.”

Suggestions for accommodating motherhood in the art world

Most artists I interviewed emphasized the importance of grants and residency programs to continue making art after giving birth. Some described using unrestricted grants to help pay for childcare while at a residency or while executing specific projects, and cited awards programs like the Sustainable Arts Foundation, whose mission is to fund artists (of both genders) with at least one child under 18.

Several artists also described the difficulty of leaving young families for out-of-town residency programs and praised programs like that of the Headlands Center for the Arts that provide living accommodations for entire families. Some suggested that grant and residency programs set aside a limited number of spots for artists with children to encourage family balance, not just unrestricted studio time.

One visual artist with a 2.5 year old son brought up the importance of “seeing and being seen at openings;” she and most others mentioned the difficulty of fitting in this type of networking with children in the picture: “If you go to events [like openings] to try and network, or support non-friend artists—you cannot bring your kids.” Masley would like to see more galleries hold later evening weekday or weekend daytime art openings, outside the typical 6-8pm time when parents are putting young children to bed. She also believes more museums could offer special childcare rooms, citing examples at the Katonah, Aldrich and MassMOCA Museums. Several performing artists hoped for childcare at rehearsal and performance spaces.

Masley’s Momtra blog also recommends establishing not only support networks of artist-parents (who may feel isolated from their childless colleagues) but “artist baby-sitting coops.” Online resources like Momtra could be an inspiration for more mainstream service providers like local arts councils to highlight family-friendly arts institutions and resources or offer special workshops for parents.

Is balance in the arts just a women’s issue?

The artists I interviewed (and Martinez’s interviewees in Artinfo) were divided in perceiving vast differences between men and women in the art world, but several artists echoed Anne-Marie Slaughter’s belief that it is more difficult for a woman to be away from home, especially in a child’s early years.

In her article, Slaughter discusses the importance of marrying the “right person” who is “willing to share the parenting load equally (or disproportionately).” Some artists in my sample group and their freelance husbands split the caregiving. One visual artist married to a musician described the difficulty of balancing work and family when her husband is touring. When asked if it would be just as easy for her to leave her 1-year-old son if she were a musician that needed to travel, she said, “in addition to the responsibility of breastfeeding, a baby just really needs his mother.”

Visual artist Jennifer Dalton is one of several artists in the Artinfo article who mention the persisting disparities between men and women in the arts, in both earning power and exposure. She believes this makes it especially difficult for women to get ahead with children. In her longer interview published in Artinfo, Dalton describes her 2006 survey conducted with almost 900 anonymous artists, “How Do Artists Live?” “Among those responding the male artists with kids had the highest percentage (approximately 50 percent) of gallery representation. Female artists with kids had the lowest percentage (approximately 20 percent). Male artists [without] kids and female artists without them were about tied, about 27-28 percent with gallery representation.”

On the flip side, male artists may face different pressures that discourage fatherhood, as suggested by one reader comment on the Artinfo article: “A male artist has to sacrifice family and social life in pursuit of his talent; as society expects males to be the bread winner.”

My father, Joel Gressel (also a new-music composer) landed a steady day job in the financial sector that allowed my mother to teach only part-time for ten years and pay for part-time childcare to watch me and my sister while she wrote her music at home. A few other artists discussed the importance of their partners working as the primary, if not the only, earner.

Expanding the Conversation

This exploration has led me to believe that artists able to work on flexible schedules from home are in a better position than many types of workers to forge fulfilling career trajectories that include families. Yet when babies compete with both day jobs and creative work time for scarce hours in the day, sacrifices such as scaling back hours spent on artistic work or declining networking opportunities can result. Although most artist-parents I interviewed have had at least some luck finding grants or residencies, flexible day jobs with benefits (especially in academia), spouses with stable incomes, helpful family members, etc., even these parents fear losing touch with their artistic selves and communities (in the words of Patricia Runcie, having to balance the “inner angsty artist with the person my baby sees as mommy”). I believe most of the challenges faced by artist-parents are not unique to women, but in the arts, as in other historically male-dominated fields, mothers perceive that they must work especially hard to be taken seriously after giving birth, and are vulnerable to lingering societal pressures to prioritize family over work.

I am interested in opening up this discussion to other Createquity readers–not just more women artists but male artists with (or without) children, artists in the for-profit entertainment and design industries, other arts leaders, etc. How difficult would it be for arts organizations to better accommodate the scheduling needs of parents, or for artist service organizations and grantmakers to turn their attention to parents as a group with unique needs? Are there arts fields or career options that are more family friendly than others? How are male artists coping with their own set of societal pressures? And, importantly, should the arts sector, in the words of Slaughter, “value choices to put family ahead of work just as much as those to put work ahead of family?”