In late September 2011, I started following Occupy Wall Street’s (OWS’s) Arts and Culture committee with the goal of understanding, and critiquing, its organizational structures for a Createquity article. However, I soon found that the same way the movement as a whole resists neatly following one set of demands (though its anti-corporate greed and income disparity message has always been clear), its Arts and Culture activities resist falling into one organizational model—or at least the systems are constantly evolving. This is especially the case now, well into the movement’s post-physical occupation phase. At first I thought this might present barriers to participation for artists, or to arts administrators and curators seeking to donate their organizational skills. Yet I eventually came to believe this looseness could be one of the Arts & Culture movement’s strengths—or at the very least, it has opened up a fertile space for debate about an alternative, “Occupied Art World.”

The early days: Occupation as Art and “Curating by Consensus”

The OWS movement’s inception resulted from a poster call to action by the alternative media organization Adbusters, and as many other writers have noted, arts and culture were nearly inseparable from the core actions of the movement as the encampment at Zuccotti Park grew. Early on, critics like Martha Schwendener in the Village Voice were quick to describe the park occupation itself as “a kind of art object: a living installation or social sculpture,” blurring the lines between art and life. Richard Kim in The Nation described in detail the symbiotic relationship of an Arts and Culture (A&C) working group to various life-sustaining activities in a “culture rich” Liberty Plaza during the occupation’s heyday. A&C subgroups like the Puppetry Guild added a critical visible dimension to rallies and marches, including bringing OWS to the Halloween Parade. Powerful graphic images have helped spread OWS’s message over the social media airwaves.

A Facebook post by the OWS-sympathetic arts nonprofit Creative Time in late-September first brought me (and a group of other intrigued artists/curators) down to Zuccotti Park for an organized discussion about how outside artists can get involved in the movement. This was my first introduction to the now-famous “people’s mic,” as all members of an expanding group echoed and amplified each individual participant’s brainstorms for art actions, then finally tried to reach consensus about a name for a unique art happening (at the time, the group settled on “Occupennial,” with its tone of art world satire). At this meeting, I recognized that truly joining and understanding this movement would take patience—but at the same time, there was something very liberating about this group of both established artists and curators and unknown recent college graduates where no one revealed their job title, tried assert their superiority, or asked for anyone else’s credentials.

The weeks that followed certainly brought some growing pains of what I initially perceived to be a “curating by consensus” model for art production. At another early outdoor meeting of the “Occupennial” committee, new passersby kept joining the circle and re-raising questions such as whether established “art world” professionals should be actively recruited for OWS art shows (see more on this in Art Fag City). Group participants questioned whether there was even a need for the group to exist, making any type of planning difficult. This early tension over whether arts and culture should be treated separately from other movement-oriented activity later reappeared in a more recent Nation article: “a certain suspicion regarding art as a specialized realm is encoded into the DNA of OWS.” Ultimately, rather than put on its own art event, Occupennial instead evolved into Occupy with Art, an online clearinghouse for all OWS-related art activities that also helps organize select occupation-sympathetic projects.

All official OWS groups resist hierarchical leadership in favor of the consensus-based, “horizontal” decision-making model of the NYC General Assembly (GA) (for more detail on this, see Hyperallergic’s October 20 post explaining the A&C meeting process). I have attended meetings where artists’ ideas were blocked by only a few group members, or discussed for over an hour with no agreement. Early on, I also found myself wondering if OWS could provide a viable model for the arts—or if it was in fact hampering artistic freedom and artistic quality.

Occupying Artistic Practice

However, when I decided to participate in the movement as an independent artist while the park occupation was still going strong, I found the opposite to be true. While there is a proposal vetting process within OWS for artists seeking financial and volunteer support for their projects, individual artists and artist groups do not need to go before A&C at all in order to do their own projects that align with the movement. I went to Zuccotti Park on several occasions to create plein-air drawings and paintings, before and during the November 15 park eviction. I was surprised and pleased to find myself welcomed, both by the then-occupiers of the park, and members of A&C. The latter “curated” some of the paintings first into an exhibition at Printed Matter, then into a printed book about the occupation, and shared them widely via social media, bringing the type of instant visibility and relevance that is rarely found these days in more established arts circles.

Hyperallergic published an essay by another Zuccotti occupation live painter, Karen Kaapcke, who wrote:

My work has changed — I am not quite sure how yet. I always paint from life, but the pre-verbal need to document something so important has brought me closer to what it might mean to be a painter. The other day, I sat in my studio thinking about “visual meaning,” about how to paint something essential. I knew this thought came from learning and responding to Occupy Wall Street.

Whatever its organizational strengths and shortfalls may be, the movement is full of similar stories from individual artists, as well as arts managers and curators, who have expanded both their visibility and artistic practice through the movement. James Rose, another painter who has been to many A&C group meetings and events and made numerous charcoal drawings of the park, explained, “Though I never realized it at the time, when I fist moved to New York City, I was always painting the 99%–i.e., ordinary people on subways. With OWS, I have a platform to stand on, a network. People take my work seriously. Before that, there was an invisible wall I couldn’t get through. OWS knocked that wall down. It clarified how to get my voice out there…I don’t know of many arts nonprofits that are making headlines every day.”

For others, participation perhaps has more to do with uniting art with collectivism and political engagement. At a November discussion panel, recent college graduate and active A&C member Imani Brown said of first joining the group: “The atmosphere of openness and community was immediately apparent and incredibly addictive.” Another artist participant states: “The process doesn’t lend itself well to art production. It’s more like a process of examining our underlying social values. Focusing on the important questions [raised by the movement] opens up a space of freedom—i.e., to focus on political process, a formerly marginalized space of discourse.”

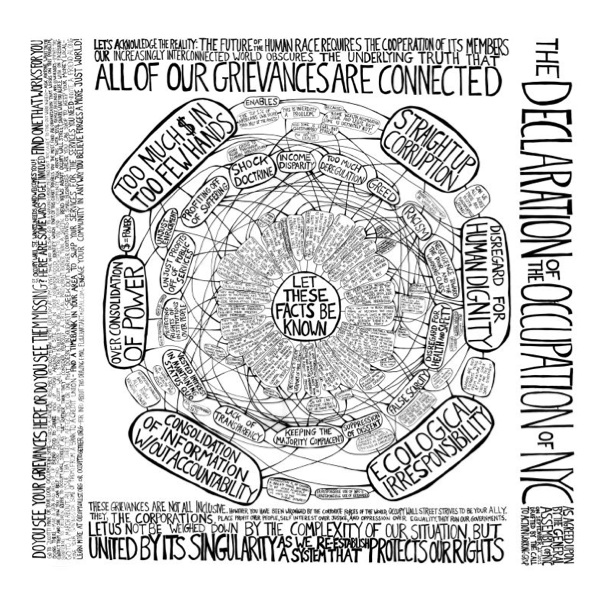

Rachel Schragis, “The Declaration of the Occupation of NYC” created for the Occupy Wall Street movement

Some artists have created work in direct partnership with OWS’s General Assembly; Rachel Schragis’s Declaration of the Occupation of NYC, now one of the most iconic images of the movement, was formulated through weeks of consensus-building– a laborious process that some artists might consider stifling to their creativity. But for artists like Schragis interested in collaborative or socially-relevant practice, OWS provides opportunities to explore new territory. This has been a space indeed ripe for artistic experimentation, maybe because there are no “rules” yet for what makes a quality “occupation” art project, or who should have the power to decide.

A Post-Occupation Art Occupation

In these post-Zuccotti days, the A&C group, like the rest of the movement, is in flux, and it continues to resist the structures of a traditional arts nonprofit. Regular meetings still occur at 60 Wall Street, of the main A&C group and constantly multiplying affinity groups. A&C was offered office space from the supportive arts blog Hyperallergic back in November, and, from what I last heard, is still determining how best to utilize it. A&C still organizes centralized actions and supports sympathetic movements (such as an upcoming Occupy Town Squares event), and numerous museums and other nonprofits are seeking to archive, present, and discourse with OWS art. Yet according to several members, the official A&C group serves more as a networking body through which new artists introduce proposals and get acquainted with the movement. Most concrete actions are now being carried out by the much smaller affinity groups and guilds, which have more consistent membership.

Some of the most recent projects seem to reinforce questions facing the movement as a whole: whether or not a physical occupation is needed for continued momentum, whether clear demands are needed, and the extent to which the movement should focus its energies on things like national politics, or courting organized labor (as Occupy with Art blogger Ismael Hossein Zadeh suggests).

To quote critic and curator Nato Thompson on the “dysfunction” of the general assembly structure, “At this point it is known that if anyone wants to get anything done, they should just do it and skip the basic organizing meetings. Or join one of the smaller groups…Without that coalescing together, the movement loses its uniqueness and historic specificity. With the loss of the squares, the movement runs the risk of becoming what it once was: A thousand different causes organizing on their issues and only remotely coming into contact with each other.”

Are the artistic activities of OWS evolving into disconnected, mainly symbolic individual efforts, albeit sympathetic and perhaps helpful to a wide range of related issues? Certain direct art actions have continued to focus on Zuccotti—for example, a January 14 event that adapted Yoko Ono’s Wish Tree project to the park and included a two-minute “die in” of people simultaneously laying still on the cold ground. This event and others have continued to draw well-known artists and press coverage. But the crowd that came to Zuccotti for the Ono event was relatively small, certainly in comparison to those of the massive marches of the early movement. At the same time, there are efforts to form stronger ties between the different arts and culture activities in NYC and those in other cities: a recent “InterOccupy Arts” arts and culture conference call involving leaders of different groups, a “Wall Street to Main Street” event bringing OWS-related art to storefronts in Catskill, NY, and various internet-based projects.

Occupying Arts Policy

One place where the OWS arts and culture movement seems not to have lost momentum is in its critique of the art world. In the first days after the eviction, at a November 19 “Occupy Wall Street: Imagining the Future” presentation/discussion at Third Ward, Imani Brown described the group’s new mission as both “actual art-making for the movement” and “actual change within the art world” which has also “been extremely corrupted.”

Martha Schwendener was one of the earliest to pick up on the fact that OWS could also be an opportunity to re-invigorate a critique of arts institutions that was long ago co-opted by those very institutions—and to create highly visible and relevant art in a completely alternative space:

The critiques offered by the OWS General Assembly overlap heavily with the art world: corporate domination of museums; art-school debt; a 1 percent system (less, really) of funding and canonization. The ’70s and ’80s saw an accelerated process of art being absorbed into institutions, and artists tried to resist it. But Institutional Critique, as it came to be called, only reinforced the fact that “liberal” institutions can absorb just about anything, including “critique.”

As shown by the testimonies of individual artists, working outside the structures of the mainstream art world could in itself be a form of institutional critique, or at least a liberating process.

So what implications, if any, do these disparate actions, working groups, and critiques have for the larger arts field?

Some obvious questions have been asked by the sometimes controversial “Occupy Museums” group (whose targets include the Museum of Natural History, Lincoln Center, and the labor union-unfriendly Sotheby’s in addition to visual art museums) and the Arts & Labor group: for example, whether large arts institutions should be admonished based on the concentration of “1%” robber barons on their boards. A December Occupy Museums protest at Lincoln Center calling attention to major donors Bloomberg LLP and Tea Party sympathizer David Koch drew sympathetic speeches from musicians Lou Reed, Phillip Glass, and Laurie Anderson. A recent January 13 occupation and General Assembly meeting at the Museum of Modern Art’s Target First Friday free public hours questioned the ethics of MoMA board members serving simultaneously on Sotheby’s board, and of corporations sponsoring free museum admission.

Arts & Labor is also pointing out the hard truths that a myriad of well-meaning artist service organizations haven’t really been able to address. Says Arts & Labor member Erin Sickler in an Art21 interview, “I have visited hundreds of artists’ studios and heard about their often-precarious economic situations. I have seen art writers, administrators, and other curators struggle to stay afloat on measly salaries with no benefits or health care. Arts & Labor is trying to break the silence around these issues…seeking to build broader solidarity with workers in other creative fields as well as other workers.”

These groups do come close to making some concrete demands: for example, after the MoMA occupation, a letter was circulated to MoMA staff offering to donate the large banner unveiled in the protest to its permanent collection, in exchange for an end to the lockout of Sotheby’s art handlers union, and for honoring the request that “Target Free Fridays” are never publicized by MoMA without citing the Artist Workers Coalition whose protests led to free museum days in the early 1970′s. I have not seen as many ideas for a complete overhaul of the current economic system, a system that includes steep museum admission fees, unpaid internships, and largely un-unionized art workers.

Amid these debates about high art school debt and low or nonexistent salaries, artists, curators, and administrators alike continue to donate countless hours to OWS, sometimes at the expense of steady income. Unlike the unpaid internships in arts nonprofits, for most of these people, OWS doesn’t seem to be a resume builder—some remain anonymous by choice, not wanting future employers to learn of their political activism. Artists, including myself, tend to go un-credited for their work in OWS exhibitions and publications, and almost always un-compensated.

To me, this is testament to the unique intrinsic benefits artists have gained from participating in the movement. Maybe it has to do with the other important components of artistic support artists get from Occupy—a massive social network, mass exposure and instant validation, copious donated art supplies and labor–which may not be possible in traditional arts institutions steeped in competitive application processes for limited space, funding and exhibition spots, not to mention the administrative burden of foundation and government funding and old modes of art criticism and curating. A heavily-involved A&C and Occupy With Art committee member also recently reminded me of the fact that 501(c)(3) organizations are sometimes uncomfortable with endorsing political activism. As the movement itself becomes increasingly disconnected from its once highly visible public square, it will merit watching whether OWS still offers artists the same type of exposure and community, and whether the lines between art and activism continue to blur to the same extent.

Art history is replete with examples of “alternative spaces” and alternative models, but is this something new altogether: something bigger, farther-reaching, and possible only in an age of social media, DIY digital expression and crowdsourced fundraising? Can this new grassroots movement sustain itself, or will it simply get absorbed into larger institutions’ political art archives? Four months after it first formed, a sizable group is still working around the clock to answer the above questions, and still making art in the process. Much like the original occupiers at Zuccotti Park, they don’t seem to be going anywhere anytime soon.