Last week’s post, provocatively titled Economists Don’t Care About Poor People, attracted two lengthy, substantive critiques. One was from Michael Rushton, with whom I’ve tangled previously on the subject, and the other from Adam Huttler. (Note to self: when your own boss writes an eleventy-thousand-word comment refuting your twelvety-thousand-word blog post, maybe it’s time to, uh, throw in the towel. Just kidding, it’s on!)

I decided to address Adam’s and Michael’s critiques together since there is some degree of overlap. Below, I’ll distill each man’s arguments into bullet-point form and number them so they can be addressed more clearly.

Adam thinks that I am overstating my case and “foster[ing] false hope in a bogus alternative.” He claims:

- My example of the Costner memorabilia auction is undermined because the dotty old rich guy does not realize what he’s buying, and thus does not have perfect information. (1)

- The goods cited in the examples given are “luxury goods” (goods in limited supply that have high demand), and thus do not typify markets in general (though Adam allows that the normal rules of supply and demand do not apply to luxury goods). (2)

- I’m missing the point of Baumol and Bowen’s argument; the real point is that producers should have the option of claiming the full value generated by their product, and they do not have the option to do so if prices are regulated. (3)

- Anyway, instituting a lottery system for ticket distribution just randomizes wealth, it doesn’t equalize it. (4)

Michael says that I’m too mean to economists and that most of them do have a heart. He writes:

- Libertarians’ arguments don’t deserve to be taken seriously, so why am I even bothering? (5)

- He doesn’t know “serious” non-libertarian economists who disagree with a vision of good policy that includes (among other things) a progressive income tax, publicly-provided health care and dental services, and public pre-school, along with most other things that the U.S. government currently provides. (6)

- Most goods in a marketplace are run-of-the-mill products that are regulated by supply and demand, and that’s okay; the things I’ve mentioned are exceptions. (2)

- “Efficiency” is a separate concept from “justice” in economics. (7)

- Instituting a lottery system for ticket distribution just randomizes wealth, it doesn’t equalize it. (4)

OK, let’s see, taking these in order from least salient to most:

First, the appropriateness of using lotteries to distribute expensive tickets to arts events (arguments #3 and 4). Adam & M-Rush’s point that lottery systems randomize wealth rather than equalize it is fair enough – I didn’t necessarily mean to hold lotteries up as the be-all and end-all, but only mentioned them since Baumol & Bowen specifically seemed to think their solution (let the free market decide) was fairer than the lottery. To Adam’s point about commercial operators having the opportunity to claim their own value, I am more sympathetic, though even in the case of some commercial entities the question may not be as easy as all that (e.g., the Red Sox employ a lottery system for distributing hot-ticket items like Yankees games; one might argue that this would be justified as an enforced policy because baseball enjoys an antitrust exemption from the government which allows the Red Sox to have the grip on Bostonians’ identity that they do). And in an environment where nonprofit arts administrators across the country are tearing their hair out trying to understand how to reach new, younger, and more diverse audiences, a lottery system is perhaps a fairer way to distribute scarce resources than relying on market forces to distribute them according to society’s existing unfairnesses.

But I don’t want to let the lottery issue distract from what I see as the bigger fish. The real question here is how well what Adam calls the price =value equation (aka neoclassical pricing theory) describes the real world and how much it influences mainstream economic thought. So let’s begin.

Regarding argument #1, I thought about the issue of perfect information, but I could just as easily have made it a situation where he was buying the memorabilia as a gift for his wife, who divorced him a year later and threw out everything he had ever given to her; or if that’s not good enough, just that it pleased him in the moment to own this item and that he bought it for no real reason other than that he could. Either way, the point still stands, if not quite as dramatically. But this is supposed to be an extreme case for purposes of illustration. The price = value equation is challenged in much subtler ways all the time.

Which brings us to #2: I’m not convinced that these “luxury goods,” and the attendant supply-and-demand weirdnesses that go along with them, are such edge cases after all. Adam goes so far as to say, “while Price = Value in the aggregate, the formula doesn’t necessarily hold for any individual purchaser.” Huh? If the formula doesn’t hold for any individual purchaser, why would we assume that it holds in the aggregate? I’m open to the possibility that it could, if confronted with irrefutable empirical evidence, but I have a hard time believing a priori that the disconnect between utility and willingness-to-pay for individual market players doesn’t bias and shape the market in specific, systematic ways. And if anything, this seems like it would be especially true in the arts. After all, the original discussion that led to all this was about whether unpaid internships were a threat to diversity in the arts because low-income individuals could not afford to take them (and thus were at risk to remove themselves from contention at the front end for an important career stepping-stone towards more potential income later on). One might think of this “willingness-to-accept” problem as a kind of corollary to the “willingness-to-pay” issue that I pointed out with my post. We also looked recently at the possibility of pernicious effects on the socioeconomic diversity of artists that compete for recognition through competitions if entry fees were raised to nontrivial prices. And it doesn’t end there, certainly. Think about what kinds of investments are needed or helpful to jumpstart an artistic career: training, documentation (e.g., recording), production values, marketing, travel, living expenses in expensive cities, time not spent earning income. If anything, in many of these situations willingness-to-pay may be inversely correlated with utility/personal value, not one and the same–not even close.

Do economists understand this? Here’s where Michael Rushton and I just don’t see eye-to-eye (arguments #5, 6, and 7). I applaud his list of policy recommendations–clearly, he is living proof that not all economists are heartless bastards. And surely there are others – Paul Krugman, for one, and the fact that the latter won the Nobel Prize speaks volumes. Perhaps the kinds of economists I want to see are more in evidence in the international community. But here in the US, I wish I could believe they were as mainstream as he says. I mean, really? No serious economists would dispute that we need government-provided universal health care and a no-fucking-around progressive income tax? Has Michael Rushton not heard of the Chicago School? Are these people not mainstream? Have they not had a tremendous formative impact on public policy in this country over the past 30 years? The foundation of their philosophy is the very libertarian principles that Michael is so quick to reject as not being worthy of debate. Yet the shadow they cast over the national discussion of economics is tremendous.

Interestingly, my two contenders reserve their strongest criticism for things I didn’t even say.

Adam, for example, concludes:

Ultimately my concern with your line of reasoning here is that I can’t see how it leads to anything but trouble. Markets are deeply imperfect, but they’re the best tool we have. To the extent that they result in undesirable outcomes, then we should seek to tweak their functioning, not abolish them in favor of some kind of centralized arbiter of happiness.

OK, so I never suggested that we abolish markets. That would be pretty nonsensical of me–after all, markets are there whether we like it or not; they happen. I think of marketplaces like biological ecosystems. Sometimes, depending on what’s going on inside of them, they work extraordinarily well, with everything going according to Nature’s plan in a sustainable, virtuous cycle. Other times, though, again depending on what’s going on a the micro level, they get out of balance; portions flourish while others flounder, leading to displacement or the loss of biodiversity or even wholesale collapse. To fix the imbalance, one must help the system to function again. Whether we call it a market or not doesn’t really matter; it is what it is.

Meanwhile, Michael thinks that I want to achieve utopia through micro-manipulation of the prices of everyday goods.

My problem with IDM is that he wants to achieve income equality through a lottery of opera tickets, where poor winners could keep them or sell them, and the rich could still obtain them. But that’s…well, goofy. This just randomizes wealth, handing out valuable tickets to a lucky few and letting them trade them. I have a better idea…

Of course a lottery of tickets isn’t going to achieve income equality. At best these measures are a small band-aid on a much larger problem, and I’m planning to address that problem in a future post. In the meantime, though, a band-aid is better than salt, is it not?

If anything, in the last two years, my orientation towards markets has become more positive, not less; I now believe that markets are one of the most efficient and effective ways of advancing the social good, when they work. So I think Adam, Michael, and I are actually in quite similar places here after all, broadly speaking. It’s just that I think of markets as systems that occasionally bear a resemblance to the idealized marketplace seen in economics textbooks, but much more often don’t.

*

Here’s the point in all of this.

I have all the respect for Adam in the world (love ya too, boss!), but I remain convinced (or at any rate, I strongly suspect) that it’s the neoclassical model that’s the edge case, not luxury goods. How common is it, really, for people to have full and relevant information on what they’re getting? How common is it that their preferences are really rational? Just because your mind works that way doesn’t mean most people’s do. Likewise, I think Michael Rushton is a smart, smart cookie, but his campaign to limit the discussion to (what seems to me) a relatively narrow group of middle-of-the-road, professional academic economists does a disservice by ignoring the vastly disproportionate impact that the free-market purists have on the national conversation. Dude, if you want to call yourself an economist and be proud of it, you need to take some responsibility for the damage your crazy-ass colleagues are doing to the credibility of your profession.

Rushton thinks it’s unfair that I implied that William Baumol and William Bowen don’t care about poor people, when clearly they do. I agree that it’s an unfair characterization. But I need to explain something about that quote in my last post. For those who have not had the opportunity to read Performing Arts: The Economic Dilemma, the book is through most of its pages a model of “telling it like it is” understatement: the authors clearly identify the limits of their knowledge and analysis, every assertion is thoroughly documented, a host of alternative explanations are examined at every turn, and issues of class, race, and gender are given fairly enlightened treatment by 1966 standards. In short, they approach the issues at hand exactly in the way I would ask.

The outburst I quoted on page 286 is not an offhand remark taken out of context; it is part of an impassioned five-page rant that is completely at odds with the tone seen in the rest of the book. The authors offer no empirical evidence for their claims in this section, only a few quotes from historians and their own very obvious frustration (some of it perhaps justified) at overzealous regulation of ticket prices. Clearly, one if not both of the authors felt very strongly about this issue, strongly enough to break with decorum and tone to take a stand. That they did it while disparaging the notion of “public virtue” and ignoring the very obvious benefits to access for lower-income people (remember, it’s not like these were considered and dismissed, they weren’t even discussed) from one of the suggested solutions, a lottery system, is telling to me. It’s like even Baumol and Bowen suffered from a temporary bout with Econ 101 disease.

*

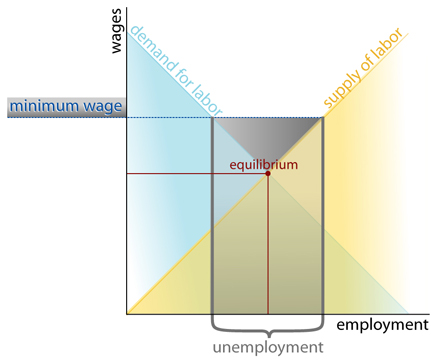

I’ve used the words “sickness” and “disease” before to describe what I feel is wrong with the economics profession. I do not use these terms lightly. I use them because, though I am ready to believe that the field has no shortage of thoughtful, level-headed, and compassionate people working diligently within it, I truly believe that as a field itself its foundations are rotten at the core. The neoclassical pricing model is not just some important but outdated anachronism in the history of intellectual thought, like Freud’s Oedipal complex or Marx’s proletariat. It is the active basis of the majority of economists’ working lives. It is the foundation of all economists’, and a lot of non-economists’, first instruction in the field. This conversation, again, was prompted by a debate about the minimum wage. If Wikipedia is to be believed, the empirical evidence that a minimum wage is even marginally detrimental to employment totals is inconclusive at best. Yet according to the same source, nearly all economics textbooks have a nice, neat graph that explains exactly why a minimum wage is detrimental to employment totals. It generally looks something like this:

That graph is in my textbook, too, Pindyck and Rubinfeld 5th Edition, right on page 299. I believe that practices like this foster an anti-scientific a priori mindset in the economics profession that hamstrings progress. It empowers those with libertarian leanings to pollute and distract the conversation with theorems proving the supposed moral righteousness of their views, and forces even economists who stray from the neoclassical model to define themselves in opposition to it, to acknowledge its primacy in the face of competing evidence. Assuming for the moment that textbooks are a reflection of what a field thinks about itself, if the textbooks started from the premise of, “this is how markets might work in a laboratory, but we recognize that real life is much more complicated than that,” I would be satisfied. If the textbooks started out by asking questions rather than providing answers, I would be satisfied. If textbooks treated micro and macro as the same thing on different scales rather than two totally separate disciplines, I would be satisfied. If textbooks addressed the issue of externalities and public goods sooner than page 621 (which is where they first pop up in mine), I would be satisfied. If every graph in an economics textbook was taken from an empirical study with true causal implications rather than from a calculus problem set, I would be satisfied. But so long as these things remain the way they are, no, I will not be satisfied with the economics profession.

That graph is in my textbook, too, Pindyck and Rubinfeld 5th Edition, right on page 299. I believe that practices like this foster an anti-scientific a priori mindset in the economics profession that hamstrings progress. It empowers those with libertarian leanings to pollute and distract the conversation with theorems proving the supposed moral righteousness of their views, and forces even economists who stray from the neoclassical model to define themselves in opposition to it, to acknowledge its primacy in the face of competing evidence. Assuming for the moment that textbooks are a reflection of what a field thinks about itself, if the textbooks started from the premise of, “this is how markets might work in a laboratory, but we recognize that real life is much more complicated than that,” I would be satisfied. If the textbooks started out by asking questions rather than providing answers, I would be satisfied. If textbooks treated micro and macro as the same thing on different scales rather than two totally separate disciplines, I would be satisfied. If textbooks addressed the issue of externalities and public goods sooner than page 621 (which is where they first pop up in mine), I would be satisfied. If every graph in an economics textbook was taken from an empirical study with true causal implications rather than from a calculus problem set, I would be satisfied. But so long as these things remain the way they are, no, I will not be satisfied with the economics profession.