(photo courtesy Flickr user victoriabernal, Creative Commons license)

(photo courtesy Flickr user victoriabernal, Creative Commons license)

So, in case you haven’t noticed, the arts have become a bit of a hot topic in the political arena lately. Though the brouhaha regarding the NEA’s involvement in the United We Serve conference calls seems to have died down a bit since Yosi Sergant fell on his sword, conservatives have been trying to expand the fight to other arenas, like the meeting with arts community activists in May and now, the Obamas’ choice of art to decorate the White House itself. As Janet Brown of Grantmakers for the Arts has pointed out, it’s silly to think this is about anything other than the fact that, in the words of Alan Grayson, “if the President has a BLT tomorrow, the Republicans will try to ban bacon.” For conservatives, this is about fighting Obama wherever and whenever they can, using any pretext possible, to try to slow him down and obstruct any change from happening. And if the arts have to be a casualty of that, clearly they could care less, even if an offspring or two has to suffer for it.

One of my great frustrations of the past couple of months, though, has been that many on the left seemingly could care less as well. A simple comparison of the play that the NEA/Yosi Sergant story received on each side of the aisle will serve to illustrate my point. Every time a “new” revelation from Patrick Courrielche’s closet of secrets came out on Big Hollywood, the story would receive the royal treatment from the conservative elite: front-page posts on Michelle Malkin and Instapundit, live television interviews on Beck and Hannity, extensive, day-after-day coverage from the Washington Times, etc. In contrast, the liberal media pretty much hit the snooze button until people’s heads started to roll. The controversy was virtually invisible on Daily Kos, one of the most popular left-leaning community blogs, despite my own best efforts in cross-posting three articles from Createquity there. Aside from a bit of coverage by Mother Jones and Huffington Post, there was barely any attempt to rally the troops in defense of the NEA on the part of the left until after the damage was already done (and only a halfhearted one even then). I don’t know about you, but I’m tired of artists caring far more about liberal politics than liberal politics cares about them.

And what of the arts blogosphere? When Courrielche’s story first came out, there was a lot of hemming and hawing in our corner that took most of the (as it turned out, borderline delusional) speculation in his original essay at face value — which, in some cases, only served to hand a hatchet to those who were on the lookout for one. This is my second great frustration with how this whole business played out. Look, you can think what you want about the appropriateness or lack thereof of the idea behind getting artists involved in a national community service initiative. But understand this: the Right is not interested in having a reasoned, constructive dialogue with you about the ways in which this concept could have been approached differently or could have delivered better outcomes for the American people. The Right wants an excuse, any excuse at all, to rip the President and anyone involved with his administration to rhetorical (and for some of them, literal) shreds. And if your words end up being that excuse, don’t act all surprised after the fact.

My final frustration relates to the NEA’s own handling of the situation. The communications office appeared completely blindsided by this attack and clearly thought that by stonewalling the inquiries it was suddenly getting from conservative media outlets, the issue would just go away. Instead, the lack of a response just provided more fuel to the fire, hampered the Endowment’s credibility, and gave the story new life every day that clear answers were not forthcoming. Then, by demoting Sergant and ultimately accepting his resignation, the NEA opened itself up to charges of “why are you disciplining him if you’re saying he didn’t do anything wrong?” I obviously wasn’t there, but to me the NEA’s actions during this period look an awful lot like those of an institution paralyzed by fear – ironic, since the great majority of the facts were ultimately on its side.

Taken together, it’s a sad commentary on the state of arts advocacy, both in terms of how others advocate for us and how we advocate for ourselves.

Which leads me to wonder: maybe we have our advocacy strategy all wrong, or at least wrong for this moment in history and this particular political environment. Despite the arts’ best efforts to slink away into nonpartisan anonymity after the culture wars of the late ’80s and early ’90s, we are now finding that the resulting gains in public investment have not only been modest but exceedingly fragile. What this summer has made clear is that conservatives love to pick on the arts. Like bullies of all stripes, they love it because it’s easy. And it’s easy because we’re small, because we’re poorly organized, and because we have no one to defend us – we’re nonpartisan, remember?

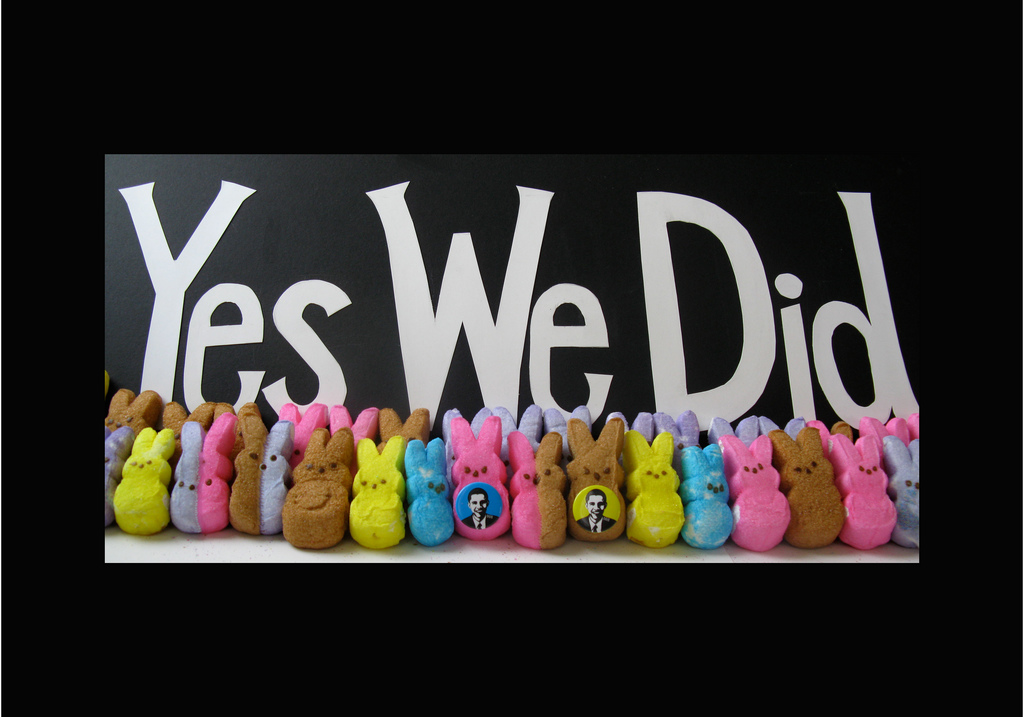

I don’t like the increasing polarization in American politics any more than you do, but maybe it’s time for us to recognize that it’s happening whether we like it or not. And given that one side has demonstrated, over and over again, that it is willing to ignore both facts and reason in pursuing its attacks against who we are and what we do, maybe, just maybe, we should think about allying ourselves with the other side in a more formal way.

What might this look like? As nonprofit organizations, most arts groups are limited in the amount of direct lobbying they can do, and they cannot endorse specific candidates. That’s not what I’m talking about, though. I’m talking about seeking a shift in the dialogue of the thought leaders on the left. I’m talking about making the arts a “progressive” issue in the same way that environmentalism, health care, reproductive rights, and labor are considered “progressive” issues. To be sure, this would lose us some fans and invite lots of confrontation, both of which are in a vacuum Very Bad Things. But it would bring with it an advantage, a huge, huge advantage: the machinery, infrastructure, and commitment of one of the two major political parties in the US–the one that at the moment just happens to have led in party identification among voters nationally for the past four years running. This is no small matter. For all the vitriol (and sometimes worse) that has been hurled at abortion-rights supporters since 1973, Roe v. Wade still stands. And where do you think the labor movement would be in this country without the strong support of Democrats through the years?

An alliance between the arts and the left makes a lot of sense on both sides. Most artists themselves identify as anywhere from moderately liberal to borderline Marxist, as do their core audiences. Art production and presentation has historically been concentrated on the coasts, in urban areas, and in town centers, a fact of life decried by some but that nevertheless aligns well with the progressive focus on cities and existing concentrations of progressives. Richard Florida’s “creative class” concept and the arts’ neighborhood-revitalization powers provide us with an opening; it’s up to us to use it wisely. Just as there is a movement of “greening” cities underway, there should be a movement of “arting” cities: providing color, infrastructure, and life to neighborhoods and communities as we clean them up and get them ready for the 21st century. Part of the reason culture conservatives hate the NEA so is because so much art speaks to largely progressive groups: homosexuals, atheists, people of color, the sexually liberated, the alienated, the outsiders. One could even make an argument that art and creativity are inherently progressive values: they require and celebrate a capacity to think critically, to question convention, to consider different viewpoints. Is it time for us to come out of the political closet and show the world who we really are?