During my time as a Createquity Writing Fellow I’ve written a lot about museums partly because I am a museum professional, and largely because, being already keyed into the museum world, I find that there is just so much to write about. Although I had been aware of Fractured Atlas’s work for a long time, I first heard about Createquity when a well-known museum blogger, Nina Simon, wrote about it on her blog Museum 2.0. Simon appreciates that Createquity provides “exposure to a broader arts world.” She’s correct in her assessment that the museum world can be an insular bubble – for all the work we do on engaging our audiences and our communities, we do most of it through a museum-specific lens.

Later in that same post, though, Simon writes, “the American ‘arts’ field is in as much of a bubble as the museum industry–perhaps even a smaller one.” She refers to the museum and arts bubbles as separate, even though many people would consider museums to be a part of the arts. In some ways they are, but in many ways they are not. I get the impression, for example, that large orchestras, small community-based dance troupes, and off-Broadway theaters speak the same language and spend time in the same bubble more than museums interact with any of them. This raises the question – what is a museum? Can we define museums as arts institutions, or do they fit better in another category?

The whole idea of museums as art institutions is based on an implicit assumption that art museums are typical of all museums. It’s true that the traditional mores of a museum atmosphere – quiet, solemn, reflective, reverent – are based in the heritage of art museums. However, museums are much more diverse than that. Of the museums that were accredited by the American Association (now Alliance) of Museums as of 2012 (which is a small sample of the museums in the US), 10% were general or multidisciplinary, and 8% were focused on natural history or anthropology. Science and technology museums, children’s museums, and many history, anthropology, and natural history museums define their goals very differently than a traditional art museum. For example, the Association of Science-Technology Centers says, “Science centers encourage the innate curiosity that resides in all of us, providing opportunities for education, awareness of social and global issues, even recreation.” Many museums are arts institutions, but the term “arts” is inadequate to describe the breadth of the museum field.

For this reason, museums are often described as cultural institutions, rather than arts institutions. This definition is useful because it is broad enough to capture many of the goals of many museums: culture can mean the body of concepts shared in a society (the sociological view), or it can mean the achievements a society has deemed to be most important (“high” culture).

Andrew Sayers, the director of the National Museum of Australia, believes museums fit better in the education category. Responding to a discussion paper on Australia’s National Cultural Policy, then in the process of being revised, Sayers wrote a piece for The Australian titled, “Redefine Museums as Educational Resources.” Sayers argues that museums’ contributions to both school education and the advancement of knowledge in society makes them distinct from arts organizations. While Sayers does see museums as a part of “cultural heritage,” a category in Australia’s National Cultural Policy, he fears viewing them solely through this lens makes them look like storage facilities. “We need to redefine museums as educational resources rather than as buildings where collections are held.” I couldn’t agree more. Holding collections will always be an important and unique function of museums, but their primary relevance to society is their capacity to educate and inspire. As Sayers says, “there is hardly a work of nonfiction or a documentary produced in this country that doesn’t make extensive use of the resources in our collecting institutions.”

Despite museums’ value as cultural and educational resources, key policymakers view museums as luxuries, a leisure activity for the wealthy. This attitude may stem from the idea that visiting museums is solely a leisure pastime for a narrow set of people who see themselves and their values reflected in the museum’s content and presentation, which has merit only in the fact that historically it has sometimes been true. However, this is increasingly inaccurate as museums strive to diversify and reflect their communities. While both the arts and museums would benefit from a reversal of this view, museums as a whole offer different benefits to society than other arts organizations do.

Indeed, the concept of museums as educational institutions challenges their association with luxury or leisure. As repositories for knowledge, expertise, and research, museums complement the educational function of universities and private centers. According to Sayers, “museums are an integral part of education across many areas of the curriculum and are immense resources for the understanding of history, society and science.” While countless studies in the last few decades have shown the educational benefits of music, dance, and visual arts, museums teach content across disciplines, and at their best can teach critical thinking skills beyond the arts.

In their 2011 article “Museums and the Future of Education,” Scott Kratz and Elizabeth Merritt provide several examples of ways museums do this, from collaboration with schools to independent learning in museum galleries. The National Building Museum has a curriculum for schools called “Bridge Basics,” which teaches students to identify problems, experiment with solutions, and evaluate results as well as math and engineering concepts. Kratz and Merritt predict museum learning will become more vital as educational models change. “The future of education may well be one characterized by self-directed, passion-based learning. In this future, museums can play a crucial role in helping learners discover their passion, providing resources and opportunities to pursue this passion and training educators in the skills of experiential learning.” They argue the current trend towards standardization in schools is rapidly becoming outmoded – the Mark Twain quote “never let schooling get in the way of your education” comes to mind – and museums are already good at promoting a broader way of teaching.

While defining museums as educational institutions captures a lot of what a wide variety of museums do, the fact is, many adults don’t or won’t go to museums for their own education, seeing them as stuffy and school-like, child-like, or unnecessary. There are two ways museums can respond: show adults that education doesn’t have to be stuffy, or avoid branding themselves as educational.

In truth, people use museums for different things, and these uses coexist. The growing body of museum audience research suggests that people visit museums for a variety of reasons, different visitors may seek diverse experiences from the same museum, and one visitor may even seek diverse experiences in different visits to the same museum. John Falk has devoted his research to describing museum visitors by the identity they take on: from facilitators, who enjoy a museum through introducing their child or guests to it, to explorers, who are looking for whatever grabs them. In their book Life Stages of the Museum Visitor, Susie Wilkening and James Chung of Reach Advisors, Inc. discuss similarities and differences across generations in what visitors look to get out of a museum experience. The work of Falk, Wilkening, Chung, and others shows that museums can and do fill a variety of needs, and this multiplicity is a strength that allows them to better reach their audiences.

The definition that may best capture all museums is that they are inspirational institutions. Branding museums as inspirational emphasizes the joyous side of learning. While a few may consider inspiration a luxury, there is definitely an argument, one grounded in psychology, that inspiration is a part of education and other elements of personal and cognitive growth.

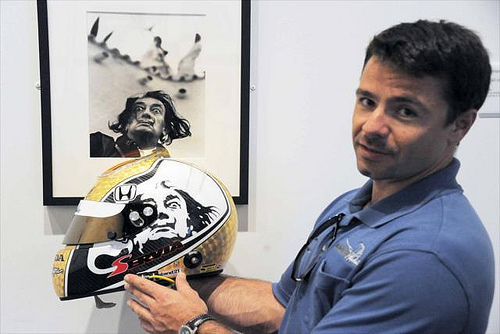

At the Dali Museum in Florida, by IZOD IndyCar Series on Flickr.

Alain de Botton, a radio host and columnist for the BBC, suggests museums have the potential to be more inspiring if they move away from canonical standards (in art, for example) and instead challenge people to think and feel more. He suggests that if museums do this, they have the potential to be our culture’s greatest inspirational institutions, filling the role churches have had in the past. I think de Botton is on to something, but he takes a narrow view and considers the most static, old-fashioned museums to be representative of them all. It isn’t canonical standards themselves that are the problem, it’s pushing them top-down on visitors instead of using them as a starting point for discussion. Museums are all inspirational in character and intent, even if not all of them reach their full potential to inspire. There are already plenty of visitors (Falk calls them “rechargers”) who find themselves awestruck by an object in a very traditional museum, and may seek out museums for this experience. In the last few decades, as the museum field has grown more serious about independent learning, deep audience engagement, and participation, museums have been able to bring that inspirational experience to more of their visitors.

A wide variety of museums share the ability to inspire visitors by the process of discovery, as exhibits demonstrate what a wide world it is or how deep a concept can go. To use some personal examples, my first exposure to cultures very different from my own was when I became fascinated by a seventh century statue of the Chinese Buddhist figure Guan-Yin in a university art museum. As an adult, I fell in love with the Mathematica exhibit at the Boston Museum of Science, which explores a variety of topics in math. An equally diverse group of museums moves visitors to be inspired by human achievements, whether an accomplishment of art or craftsmanship, ingenuity, or the triumph of the spirit in the face of adversity. I felt similarly struck by what my fellow humans can do when surrounded by Monet paintings at the Musee de L’Orangerie and when drawn through the story of the founding of the Red Cross at a museum devoted to its history. Last but not least, museums on any subject can inspire visitors to question their assumptions and examine what’s in front of them from many points of view. I had that experience myself as a young child playing at different careers at a children’s museum, and any time I learn more about prehistoric ocean life I think long and hard about my place in the universe. This common ability to inspire, more than art, culture or even education, defines what a museum is.